• 16204 N. Florida Ave. • Lutz, FL 33549 • 1.800.331.8378 • www.parinc.com

BRIEF®2: Interpretive Report Copyright © 1996, 1998, 2000, 2015 by PAR. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in whole or in

part in any form or by any means without written permission of PAR.

Version: 2.4.0.0

Teacher Form Interpretive Report

by Peter K. Isquith, PhD, Gerard A. Gioia, PhD, Steven C. Guy, PhD, Lauren

Kenworthy, PhD, and PAR Staff

Client name :

Sample Client

Client ID :

111

Gender :

Male

Age :

7

Grade :

2nd

Test date :

04/14/2015

Test form :

Teacher Form

Rater name :

Not Specified

Relationship to student :

Teacher

Knows student :

Very Well

Has known student for :

9 months

Student receiving special educational

services? :

No

This report is intended for use by qualified professionals only and is not to be shared

with the examinee or any other unqualified persons.

Sample Client (111) 2

04/14/2015

Validity

Before examining the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

®

, Second Edition

(BRIEF

®

2) Teacher Form profile, it is essential to carefully consider the validity of the

data provided. The inherent nature of rating scales (i.e., relying upon a third party for

ratings of a child’s behavior) carries potential rating and score biases. The first step is to

examine the protocol for missing data. With a valid number of responses, the BRIEF2

Inconsistency, Negativity, and Infrequency scales provide additional information about

the validity of the protocol.

Missing items

The respondent completed 63 of a possible 63 BRIEF2 items. For

reference purposes, the summary table for each scale indicates

the respondent’s actual rating for each item. There are no missing

responses in the protocol, providing a complete data set for

interpretation.

Inconsistency

Scores on the Inconsistency scale indicate the extent to which the

respondent answered similar BRIEF2 items in an inconsistent

manner relative to the clinical samples. For example, a high

Inconsistency score might be associated with the combination of

responding Never to the item “Small events trigger big reactions”

and Often to the item “Becomes upset too easily.” Item pairs

comprising the Inconsistency scale are shown in the following

summary table. T scores are not generated for the Inconsistency

scale. Instead, the absolute value of the raw difference scores for

the eight paired items are summed, and the total difference score

(i.e., the Inconsistency score) is compared with the cumulative

percentile of similar scores in the combined clinical sample and

used to classify the protocol as either Acceptable, Questionable,

or Inconsistent. The Inconsistency score of 1 is within the

Acceptable range, suggesting that the rater was reasonably

consistent in responding to BRIEF2 items.

Item

Inconsistency items

Response

Diff

3

When given three things to do, remembers only the first

or last

Often

0

19

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Often

Sample Client (111) 3

04/14/2015

Item

Inconsistency items

Response

Diff

4

Often

0

20

Often

5

Sometimes

1

33

Often

6

Sometimes

0

14

Sometimes

12

Often

0

32

Often

16

Often

0

39

Often

22

Sometimes

0

56

Sometimes

60

Never

0

63

Never

Negativity

The Negativity scale measures the extent to which the

respondent answered selected BRIEF2 items in an unusually

negative manner relative to the clinical sample. Items comprising

the Negativity scale are shown in the following summary table. A

higher raw score on this scale indicates a greater degree of

negativity, with less than 3% of respondents scoring 5 or above in

the clinical sample.

As with the Inconsistency scale, T scores are not generated for

this scale. The Negativity score of 0 is within the acceptable

range, suggesting that the respondent’s view of Sample is not

overly negative and that the BRIEF2 protocol is likely to be valid.

Item #

Negativity items

Response

2

Resists or has trouble accepting a different way to solve a

problem with schoolwork, friends, tasks, etc.

Sometimes

11

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sometimes

31

Sometimes

34

Sometimes

37

Sometimes

43

Sometimes

45

Sometimes

49

Sometimes

Sample Client (111) 4

04/14/2015

Infrequency

The Infrequency scale measures the extent to which the

respondent endorsed items in an atypical fashion. The scale

includes three items that are likely to be endorsed in one

direction by most respondents. Marking Sometimes or Often to

any of the items is highly unusual, even in cases of severe

impairment.

Items comprising the Infrequency scale are shown in the

following summary table. A higher raw score on this scale

indicates a greater degree of infrequency, with less than 1% of

respondents scoring 1 or greater in the standardization sample.

As with the Inconsistency and Negativity scales, T scores are not

generated for this scale. The Infrequency score of 0 is within the

acceptable range, reducing the likelihood of an atypical response

pattern.

Item #

Infrequency items

Response

18

Forgets his/her name

Never

36

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Never

54

Never

End of Validity Section

Sample Client (111) 5

04/14/2015

Introduction

The BRIEF

®

2 is a questionnaire completed by parents and teachers of school-aged

children as well as adolescents ages 11 to 18. Parent and teacher ratings of executive

functions are good predictors of a child’s or adolescent’s functioning in many domains,

including the academic, social, behavioral, and emotional domains. As is the case for all

measures, the BRIEF2 should not be used in isolation as a diagnostic tool. Instead, it

should be used in conjunction with other sources of information, including detailed

history, other BRIEF2 and behavior ratings, clinical interviews, performance test results,

and, when possible, direct observation in the natural setting. By examining converging

evidence, the clinician can confidently arrive at a valid diagnosis and, most importantly,

an effective treatment plan. A thorough understanding of the BRIEF2, including its

development and its psychometric properties, is a prerequisite to interpretation. As

with any clinical method or procedure, appropriate training and clinical supervision are

necessary to ensure competent use of the BRIEF2.

This report is confidential and intended for use by qualified professionals only. This

report should not be released to the parents or teachers of the child being evaluated. If a

summary of the results specifically written for parents and teachers is desired, the

BRIEF2 Feedback Report can be generated and given to the interested parents and

teachers.

T scores are used to interpret the level of executive functioning as reported by parents

and teachers on the BRIEF2 rating forms. These scores are linear transformations of the

raw scale scores (M = 50, SD = 10). T scores provide information about an individual’s

scores relative to the scores of respondents in the standardization sample. Percentiles

represent the percentage of children in the standardization sample with scores at or

below the same value. For all BRIEF2 clinical scales and indexes, T scores from 60 to 64

are considered mildly elevated, and T scores from 65 to 69 are considered potentially

clinically elevated. T scores at or above 70 are considered clinically elevated.

In the process of interpreting the BRIEF2, review of individual items within each scale

can yield useful information for understanding the specific nature of the child’s

elevated score on any given clinical scale. In addition, certain items may be particularly

relevant to specific clinical groups. Placing too much interpretive significance on

individual items, however, is not recommended due to lower reliability of individual

items relative to the scales and indexes.

Sample Client (111) 6

04/14/2015

Overview

Sample’s teacher completed the Teacher Form of the Behavior

Rating Inventory of Executive Function

®

, Second Edition

(BRIEF

®

2) on 04/14/2015. There are no missing item responses in

the protocol. Responses are reasonably consistent. The

respondent’s ratings of Sample do not appear overly negative.

There were no atypical responses to infrequently endorsed items.

In the context of these validity considerations, ratings of Sample’s

executive function exhibited in everyday behavior reveal some

areas of concern.

The overall index, the GEC, was clinically elevated (GEC T = 72,

%ile = 98). The BRI, ERI, and CRI were all elevated (BRI T = 78,

%ile = 99; ERI T = 62, %ile = 88, CRI T = 70, %ile = 95),

suggesting self-regulatory problems in multiple domains.

Within these summary indicators, all of the individual scales are

valid. One or more of the individual BRIEF2 scales were elevated,

suggesting that Sample exhibits difficulty with some aspects of

executive function. Concerns are noted with his ability to resist

impulses, be aware of his functioning in social settings, react to

events appropriately, get going on tasks, activities, and

problem-solving approaches, sustain working memory, plan and

organize his approach to problem solving appropriately, be

appropriately cautious in his approach to tasks and check for

mistakes and keep materials and his belongings reasonably well

organized. Sample’s ability to adjust well to changes in

environment, people, plans, or demands is not described as

problematic by the respondent.

Current models of self-regulation suggest that behavior

regulation and/or emotion regulation, particularly inhibitory

control, emotional control, and flexibility, underlie most other

areas of executive function. Essentially, one needs to be

appropriately inhibited, flexible, and well-modulated

emotionally for efficient, systematic, and organized problem

solving to take place. Sample’s elevated scores on scales

reflecting problems with fundamental behavioral and/or

emotional regulation suggest that more global problems with

self-regulation are having a negative effect on active cognitive

problem solving. Behavior and emotion regulation concerns do

not negate the meaningfulness of the elevated CRI score. Instead,

one must simultaneously consider the influence of the

underlying self-regulation issues and the unique problems with

Sample Client (111) 7

04/14/2015

cognitive problem-solving skills.

Sample Client (111) 8

04/14/2015

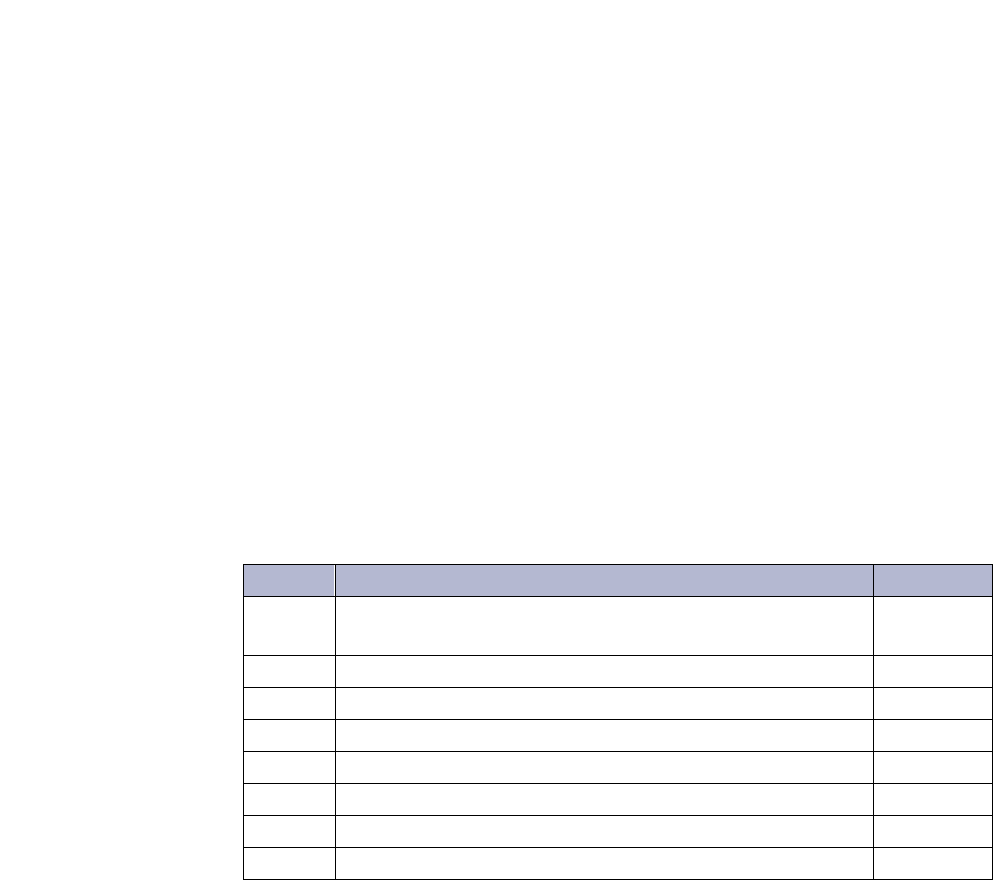

BRIEF

®

2 Teacher Score Summary Table

Index/scale

Raw score

T score

Percentile

90% C.I.

Inhibit

24

78

99

73-83

Self-Monitor

14

72

99

67-77

Behavior Regulation Index (BRI)

38

78

99

74-82

Shift

13

55

80

49-61

Emotional Control

15

66

91

62-70

Emotion Regulation Index (ERI)

28

62

88

58-66

Initiate

11

69

98

64-74

Working Memory

22

74

99

69-79

Plan/Organize

17

62

92

56-68

Task-Monitor

15

63

92

58-68

Organization of Materials

11

65

93

59-71

Cognitive Regulation Index (CRI)

76

70

95

67-73

Global Executive Composite (GEC)

142

72

98

70-74

Validity scale

Raw score

Percentile

Protocol classification

Negativity

0

98

Acceptable

Inconsistency

1

98

Acceptable

Infrequency

0

99

Acceptable

Note: Male, age-specific norms have been used to generate this profile.

For additional normative information, refer to Appendixes A–C in the BRIEF

®

2 Professional Manual.

Sample Client (111) 9

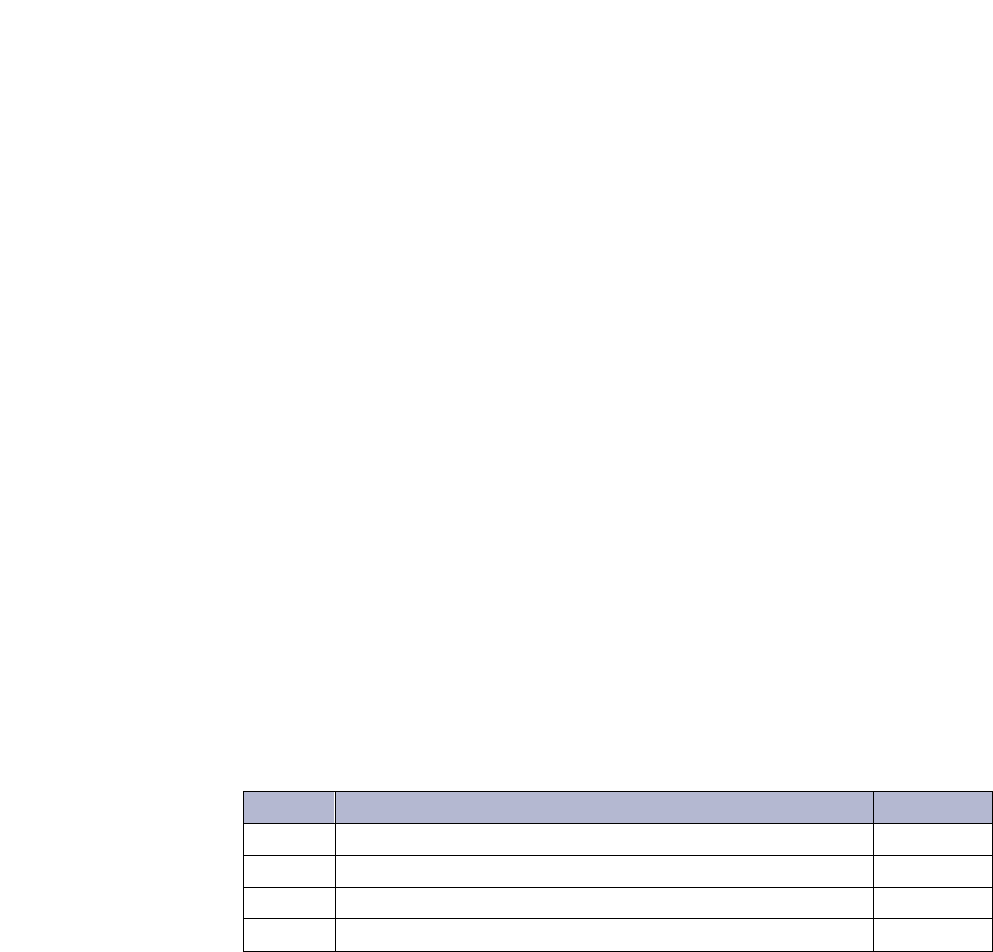

04/14/2015

Profile of BRIEF

®

2 T Scores

Note: Male, age-specific norms have been used to generate this profile.

For additional normative information, refer to Appendixes A–C in the BRIEF

®

2 Professional Manual.

Sample Client (111) 10

04/14/2015

Clinical Scales

The BRIEF2 clinical scales measure the extent to which the respondent reports problems

with different types of behavior related to the nine domains of executive functioning.

The following sections describe the scores obtained on the clinical scales and the

suggested interpretation for each individual clinical scale.

Inhibit

The Inhibit scale assesses inhibitory control and impulsivity. This

can be described as the ability to resist impulses and the ability to

stop one’s own behavior at the appropriate time. Sample’s score

on this scale is clinically elevated (T = 78, %ile = 99) as

compared to his peers. Children with similar scores on the Inhibit

scale typically have marked difficulty resisting impulses and

difficulty considering consequences before acting. They are often

perceived as (1) being less in control of themselves than their

peers, (2) having difficulty staying in place in line or in the

classroom, (3) interrupting others or calling out in class

frequently, and (4) requiring higher levels of adult supervision.

Often, caregivers and teachers are particularly concerned about

the verbal and social intrusiveness and the lack of personal safety

observed in children who do not inhibit impulses well. Such

children may display high levels of physical activity,

inappropriate physical responses to others, a tendency to

interrupt and disrupt group activities, and a general failure to

look before leaping.

In the contexts of the classroom and assessment settings, children

with inhibitory control difficulties often require a higher degree

of external structure to limit their impulsive responding. They

may start an activity or task before listening to instructions,

before developing a plan, or before grasping the organization or

gist of the situation.

Examination of the individual items that comprise the Inhibit

scale may be informative and may help guide interpretation and

intervention.

Item #

Inhibit items

Response

1

Is fidgety

Often

10

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Often

Sample Client (111) 11

04/14/2015

Item #

Inhibit items

Response

16

Often

24

Often

30

Often

39

Often

48

Often

58

Often

Self-Monitor

The Self-Monitor scale assesses awareness of the impact of one’s

own behavior on other people and outcomes. It captures the

degree to which a child or adolescent is aware of the effect that

his or her behavior has on others and how it compares with

standards or expectations for behavior. Sample’s score on the

Self-Monitor scale is clinically elevated, suggesting substantial

difficulty with monitoring his behavior in social settings (T = 72,

%ile = 99). Children with similar scores tend to show limited

awareness of their behavior and the impact it has on their social

interactions with others.

Item #

Self-Monitor items

Response

4

Is unaware of how his/her behavior affects or bothers

others

Often

13

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Often

20

Often

26

Sometimes

59

Often

Sample Client (111) 12

04/14/2015

Shift

The Shift scale assesses the ability to move freely from one

situation, activity, or aspect of a problem to another as the

circumstances demand. Key aspects of shifting include the ability

to make transitions, tolerate change, problem solve flexibly,

switch or alternate attention between tasks, and change focus

from one task or topic to another. Mild deficits may compromise

efficiency of problem solving and result in a tendency to get

stuck or focused on a topic or problem, whereas more severe

difficulties can be reflected in perseverative behaviors and

marked resistance to change. Sample’s score on the Shift scale is

within the average range compared with peers (T = 55, %ile = 80).

This suggests that Sample is generally able to change from task to

task or from place to place without difficulty, is able to think of or

accept different ways of solving problems, and is able to

demonstrate flexibility in day-to-day activities.

Item #

Shift items

Response

2

Resists or has trouble accepting a different way to solve a

problem with schoolwork, friends, tasks, etc.

Sometimes

11

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sometimes

17

Sometimes

31

Sometimes

40

Never

49

Sometimes

60

Never

63

Never

Sample Client (111) 13

04/14/2015

Emotional Control

The Emotional Control scale measures the impact of executive

function problems on emotional expression and assesses a child’s

ability to modulate or regulate his or her emotional responses.

Sample’s score on the Emotional Control scale is potentially

clinically elevated compared with peers (T = 66, %ile = 91). This

score suggests marked concerns with regulation or modulation of

emotions. Sample likely overreacts to events and likely

demonstrates sudden outbursts, sudden and/or frequent mood

changes, and excessive periods of emotional upset. Poor

emotional control is often expressed as emotional lability, sudden

outbursts, or emotional explosiveness. Children with difficulties

in this domain often have overblown emotional reactions to

seemingly minor events. Caregivers and teachers of such children

frequently describe a child who cries easily or laughs hysterically

with small provocation or a child who has temper tantrums of a

frequency or severity that is not age appropriate.

Item #

Emotional Control items

Response

6

Has explosive, angry outbursts

Sometimes

14

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sometimes

22

Sometimes

27

Sometimes

34

Sometimes

43

Sometimes

51

Never

56

Sometimes

Sample Client (111) 14

04/14/2015

Initiate

The Initiate scale reflects a child’s ability to begin a task or

activity and to independently generate ideas, responses, or

problem-solving strategies. Sample’s score on the Initiate scale is

potentially clinically elevated compared with peers (T = 69, %ile =

98). This suggests that Sample has marked difficulties getting

going on tasks, activities, and problem-solving approaches. Poor

initiation typically does not reflect noncompliance or disinterest

in a specific task. Children with initiation problems typically

want to succeed at and complete a task, but they have trouble

getting started. Caregivers of such children frequently report

observing difficulties getting started on homework or chores,

along with a need for extensive prompts or cues to begin a task

or activity. Children with initiation difficulties are at risk for

being viewed as unmotivated. In the context of psychological

assessment, initiation difficulties are often demonstrated in the

form of slow speed of output despite prompts to work quickly

and difficulty generating ideas such as for word and design

fluency tasks. There is often a need for additional prompts from

the examiner to begin tasks in general. Alternatively, initiation

deficits may reflect depression, and this should particularly be

examined if this finding is consistent with the overall affective

presentation of the child.

Item #

Initiate items

Response

9

Is not a self-starter

Sometimes

38

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Often

50

Often

55

Often

Sample Client (111) 15

04/14/2015

Working Memory

The Working Memory scale measures online representational

memory—that is, the capacity to hold information in mind for the

purpose of completing a task; encoding information; or

generating goals, plans, and sequential steps to achieve goals.

Working memory is essential to carrying out multistep activities,

completing mental manipulations such as mental arithmetic, and

following complex instructions. Sample’s score on the Working

Memory scale is clinically elevated compared with peers (T = 74,

%ile = 99). This suggests that Sample has substantial difficulty

holding an appropriate amount of information in mind or in

active memory for further processing, encoding, and/or mental

manipulation. Further, Sample’s score suggests difficulties

sustaining working memory, which has a negative impact on his

ability to remain attentive and focused for appropriate lengths of

time. Caregivers describe children with fragile or limited

working memory as having trouble remembering things (e.g.,

phone numbers or instructions) even for a few seconds, losing

track of what they are doing as they work, or forgetting what

they are supposed to retrieve when sent on an errand. They often

miss information that exceeds their working memory capacity

such as instructions for an assignment. Clinical evaluators may

observe that Sample cannot remember the rules governing a

specific task (even as he works on that task), rehearses

information repeatedly, loses track of what responses he has

already given on a task that requires multiple answers, and

struggles with mental manipulation tasks (e.g., repeating digits

in reverse order) or solving arithmetic problems that are orally

presented without writing down figures.

Appropriate working memory is necessary to sustaining

performance and attention. Parents of children with difficulties in

this domain report that they cannot stick to an activity for an

age-appropriate amount of time and that they frequently switch

or fail to complete tasks. Although working memory and the

ability to sustain it have been conceptualized as distinct entities,

behavioral outcomes of these two domains are often difficult to

distinguish.

Item #

Working Memory items

Response

3

When given three things to do, remembers only the first

or last

Often

Sample Client (111) 16

04/14/2015

Item #

Working Memory items

Response

12

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Often

19

Often

25

Often

28

Often

32

Often

41

Sometimes

46

Sometimes

Sample Client (111) 17

04/14/2015

Plan/Organize

The Plan/Organize scale measures a child’s ability to manage

current and future-oriented task demands. The scale has two

components: Plan and Organize. The Plan component captures

the ability to anticipate future events, to set goals, and to develop

appropriate sequential steps ahead of time to carry out a task or

activity. The Organize component refers to the ability to bring

order to information and to appreciate main ideas or key

concepts when learning or communicating information. Sample’s

score on the Plan/Organize scale is mildly elevated compared

with peers (T = 62, %ile = 92). This suggests that Sample has some

difficulty with planning and organizing information, which has a

negative impact on his approach to problem solving. Planning

involves developing a goal or end state and then strategically

determining the most effective method or steps to attain that

goal. Evaluators can observe planning when a child is given a

problem requiring multiple steps (e.g., assembling a puzzle or

completing a maze). Sample may underestimate the time

required to complete tasks or the level of difficulty inherent in a

task. He may often wait until the last minute to begin a long-term

project or assignment for school, and he may have trouble

carrying out the actions needed to reach his goals.

Organization involves the ability to bring order to oral and

written expression and to understand the main points expressed

in presentations or written material. Organization also has a

clerical component that is demonstrated, for example, in the

ability to efficiently scan a visual array or to keep track of a

homework assignment. Sample may approach tasks in a

haphazard fashion, getting caught up in the details and missing

the big picture. He may have good ideas that he fails to express

on tests and written assignments. He may often feel

overwhelmed by large amounts of information and may have

difficulty retrieving material spontaneously or in response to

open-ended questions. He may, however, exhibit better

performance with recognition (multiple-choice) questions.

Item #

Plan/Organize items

Response

7

Does not plan ahead for school assignments

Often

15

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sometimes

23

Sometimes

Sample Client (111) 18

04/14/2015

Item #

Plan/Organize items

Response

35

Often

44

Sometimes

52

Sometimes

57

Never

61

Sometimes

Task-Monitor

The Task-Monitor scale assesses task-oriented monitoring or

work-checking habits. The scale captures whether a child

assesses his or her own performance during or shortly after

finishing a task to ensure accuracy or appropriate attainment of a

goal. Sample’s score on the Task-Monitor scale is mildly elevated,

suggesting some difficulty with task monitoring (T = 63, %ile =

92). Children with similar scores tend to be less cautious in their

approach to tasks or assignments and often do not notice and/or

check for mistakes. Caregivers often describe children with

task-oriented monitoring difficulties as rushing through their

work, as making careless mistakes, and as failing to check their

work. Clinical evaluators may observe the same types of

behavior during formal assessment.

Item #

Task Monitor items

Response

5

Work is sloppy

Sometimes

21

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sometimes

29

Sometimes

33

Often

42

Often

62

Often

Sample Client (111) 19

04/14/2015

Organization of

Materials

The Organization of Materials scale measures orderliness of

work, play, and storage spaces (e.g., desks, lockers, backpacks,

and bedrooms). Caregivers and teachers typically can provide an

abundance of examples describing a child’s ability to organize,

keep track of, or clean up his or her belongings. Sample’s score

on the Organization of Materials scale is potentially clinically

elevated compared with children (T = 65, %ile = 93). Sample is

described as having marked difficulty (1) keeping his materials

and belongings reasonably well organized, (2) having his

materials readily available for projects or assignments, and (3)

finding his belongings when needed. Children who have

significant difficulties in this area often do not function efficiently

in school or at home because they do not have ready access to

what they need and must spend time getting organized rather

than producing work. Pragmatically, teaching a child to organize

his or her belongings can be a useful, concrete tool for teaching

greater task organization.

Item #

Organization of Materials items

Response

8

Cannot find things in desk

Often

37

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sometimes

45

Sometimes

47

Sometimes

53

Sometimes

Sample Client (111) 20

04/14/2015

Summary Indexes and Global Executive Composite

Behavior Regulation,

Emotion Regulation,

and Cognitive

Regulation Indexes

The Behavior Regulation Index (BRI) captures the child’s ability

to regulate and monitor behavior effectively. It is composed of

the Inhibit and Self-Monitor scales. Appropriate behavior

regulation is likely to be a precursor to appropriate cognitive

regulation. It enables the cognitive regulatory processes to

successfully guide active, systematic problem solving and more

generally supports appropriate self-regulation.

The Emotion Regulation Index (ERI) represents the child’s ability

to regulate emotional responses and to shift set or adjust to

changes in environment, people, plans, or demands. It is

composed of the Shift and Emotional Control scales. Appropriate

emotion regulation and flexibility are precursors to effective

cognitive regulation.

The Cognitive Regulation Index (CRI) reflects the child’s ability

to control and manage cognitive processes and to problem solve

effectively. It is composed of the Initiate, Working Memory,

Plan/Organize, Task-Monitor, and Organization of Materials

scales and relates directly to the ability to actively problem solve

in a variety of contexts and to complete tasks such as schoolwork.

Examination of the indexes reveals that the BRI is clinically

elevated (T = 78, %ile = 99), the ERI is mildly elevated (T = 62,

%ile = 88), and the CRI is clinically elevated (T = 70, %ile = 95).

This suggests difficulties with all aspects of executive function

including inhibitory control, self-monitoring, emotion regulation,

flexibility, and cognitive regulatory functions including ability to

sustain working memory and to initiate, plan, organize, and

monitor problem solving.

Sample Client (111) 21

04/14/2015

Global Executive

Composite

The Global Executive Composite (GEC) is an overarching

summary score that incorporates all of the BRIEF2 clinical scales.

Although review of the BRI, ERI, CRI, and individual scale scores

is strongly recommended for all BRIEF2 profiles, the GEC can

sometimes be useful as a summary measure. In this case, at least

two summary indexes are substantially different, with T scores

separated by an unusually large number of points relative to the

standardization sample, where differences of this magnitude

occurred less than 10% of the time. Thus, the GEC may not

adequately reflect the overall profile or severity of executive

function problems. With this in mind, Sample’s T score of 72

(%ile = 98) on the GEC is clinically elevated compared with the

scores of his peers, suggesting significant difficulty in one or

more areas of executive function.

Sample Client (111) 22

04/14/2015

Comparison of BRIEF2 Working Memory and Inhibit Scales

to ADHD Groups

The BRIEF2 Inhibit and Working Memory scales , in the context of a comprehensive

assessment, may be helpful in identifying children with suspected

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Theoretically, inhibitory control

enables self-regulation, and working memory enables sustained attention. It is

important at the outset, however, to appreciate the distinction between executive

functions and the diagnosis of ADHD: Executive functions are neuropsychological

constructs, whereas ADHD is a neuropsychiatric diagnosis based on a cluster of

observed symptoms. Although it is well-established that different aspects of executive

dysfunction contribute to the symptoms that characterize ADHD, executive dysfunction

is not synonymous with a diagnosis of ADHD. Further, problems with inhibitory

control and, in particular, working memory are not unique to the diagnosis of ADHD

but may be seen in many developmental and acquired conditions. Therefore, the

following analysis may be useful when there is a question about the presence or absence

of an attention disorder but should not be used in isolation or as the sole basis of

diagnosis. Information from the BRIEF2 may be helpful when combined with other

information such as parent and teacher ratings on broad-band scales, ADHD specific

scales, clinical interviews, observations and performance assessment.

Profile analyses have shown that children diagnosed with different disorders often have

recognizable and logical scale profiles on the BRIEF2. Children with ADHD, inattentive

presentation (ADHD-I) tend to have greater elevations on Working Memory,

Plan/Organize, and Task-Monitor scales than their typically developing peers but lower

scores on the BRI and ERI than children diagnosed with ADHD, combined presentation

(ADHD-C).

The BRIEF2 Teacher Form Working Memory scale exhibits limited sensitivity but good

specificity for detecting a likely diagnosis of ADHD regardless of whether inattentive or

combined type. In combined research and clinical samples, T scores of 65 or greater on

the Working Memory scale discriminated between healthy controls and children with

either the inattentive or combined type of ADHD with 74% classification accuracy. The

likelihood that a child with a T score of 65 or higher is a true case of ADHD was .86

(positive predictive value), whereas the likelihood that a child with a score below 65

would not have ADHD was .69 (negative predictive value). The likelihood of a child

being correctly identified as meeting criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD was more than 6

times greater with a Working Memory T score of 65 or greater.

The Inhibit scale can help further distinguish between children with ADHD-I versus

those with ADHD-C. Using a T score of 65 or greater, approximately 72% of children

were correctly classified as being diagnosed with ADHD-C versus ADHD-I in a

Sample Client (111) 23

04/14/2015

combined research and clinical sample. Children with T scores at or above 65 on the

Inhibit scale are 3.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with the combined type than the

inattentive type of ADHD. If the cutoff is increased to a T score of 70 or greater on the

Inhibit scale, sensitivity is reduced but specificity is increased. Children with T scores of

70 or more are more than 4 times more likely to have a diagnosis of ADHD-C than

ADHD-I.

While the BRIEF2 may be a helpful and efficient tool in evidence-based assessment for

ADHD, it is important that all relevant data be considered in the context of clinical

judgment before reaching a diagnostic decision.

In this particular profile, Teacher ratings of Sample’s working memory (T = 74, %ile =

99) are clinically elevated. T scores of 70 or greater on the BRIEF2 Teacher Form were

seen in over 40% of children clinically diagnosed with either type of ADHD but were

seen in only less than 3% of typically developing children and 4% of children with

learning disabilities. Scores at this level are more than 6 times more likely to be seen in

students diagnosed with ADHD and half as likely to be seen in typically developing

students, raising the possibility of the presence of ADHD. In considering ADHD

presentations, the Inhibit scale may be useful in the context of a significantly elevated

Working Memory scale. Sample’s ratings of his inhibitory control were also clinically

elevated (T = 78, %ile = 99). Students with significantly elevated Working Memory and

Inhibit T scores in a clinical sample were correctly classified as being diagnosed with

ADHD-C approximately 80% of the time.

Sample Client (111) 24

04/14/2015

Comparison of BRIEF2 Shift Scale to Children with Autism

Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have difficulties with executive

functions related to flexibility, planning, organization, and other aspects of

metacognition. Numerous studies have shown a signature BRIEF profile in children

with ASD with elevations across most BRIEF scales and a peak in problems captured on

the Shift scale. Parent and teacher ratings on the BRIEF2 in large numbers of clinically

referred children with well-defined ASD diagnoses showed similar patterns of

elevations on most scales with a prominent peak on the Shift scale. While the BRIEF2 is

not intended as a stand-alone diagnostic instrument, it can be useful as part of a more

comprehensive assessment for a wide range of clinical conditions. For children with

ASD, the BRIEF2 adds value to other measures of everyday functioning, social

responsiveness, and ASD characteristics in the context of medical history in reaching a

comprehensive diagnostic picture.

The BRIEF2 Teacher Form Shift scale exhibits good specificity for ruling out children

who do not have ASD. This is reflected in the positive predictive values of .92 for

teacher ratings at or above 65 and .98 when using a cutoff of 70. In clinical samples, T

scores of 65 or greater on the Shift scale discriminated between healthy controls and

children with ASD with 78% classification accuracy, and with 69% accuracy when T

scores were greater than or equal to 70. The lower classification accuracy is due to

reduced sensitivity at higher T scores for teacher ratings. The likelihood of a child being

correctly identified as meeting criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD was 10 times greater

(positive likelihood ratio = 10.83) with a Shift T score of 65 or greater, while the

likelihood of a child with an ASD being incorrectly ruled out was reduced by half

(negative likelihood ration = .41).

In this particular profile, Teacher ratings of Sample’s cognitive and behavioral flexibility

(T = 55, %ile = 80) are within normal limits. This suggests that Sample does not exhibit

the cognitive rigidity and adherence to routine and sameness that is often seen in

children diagnosed with ASD.

Sample Client (111) 25

04/14/2015

Executive Function Interventions

Ratings of Sample’s everyday functioning revealed some areas of concern.

Recommendations for interventions and accommodations are offered according to the

identified concerns. While the efficacy of each intervention has not been empirically

demonstrated, the majority are common interventions that are likely familiar to the

intervention team. These recommendations are general and are intended here as

suggestions or ideas that may be tailored to suit Sample’s needs. As with any

intervention, clinical judgment is paramount.

Remaining content redacted for sample report purposes

Sample Client (111) 26

04/14/2015

References

Braga, L. W., Rossi, L., Moretto, A. L. L., da Silva, J. M., & Cole, M. (2012). Empowering

preadolescents with ABI through metacognition: Preliminary results of a randomized

clinical trial. NeuroRehabilitation, 30, 205-212.

Chan, D. Y. K., & Fong, K. N. K. (2011). The effects of problem-solving skills training

based on metacognitive principles for children with acquired brain injury attending

mainstream schools: A controlled clinical trial. Disability & Rehabilitation, 33, 2023-2032.

Kenworthy, L., Anthony, L. G., Alexander, K. C., Werner, M. A., Cannon, L., &

Greenman, L. (2014). Solving executive functioning challenges: Simple ways to get kids with

autism unstuck and on target. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Levine, B., Robertson, I. H., Clare, L., Carter, G., Hong, J., Wilson, B. A., … & Struss, D.

T. (2000). Rehabilitation of executive functioning: An experimental-clinical validation of

goal management training. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 6,

299-312.

Marlowe, W. B. (2001). An intervention for children with disorders of executive

functions. Developmental Neuropsychology, 18, 445-454.

Wade, S. L., Wolfe, C. R., Brown, T. M., & Pestian, J. P. (2005). Can a web-based family

problem-solving intervention work for children with traumatic brain injury?.

Rehabilitation Psychology, 50, 337-345.

Wade, S. L., Wolfe, C. R., & Pestian, J. P. (2004). A web-based family problem-solving

intervention for families of children with traumatic brain injury. Behavior Research

Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 261-269.

Ylvisaker, M. (Ed.). (1998). Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: Children and adolescents

(2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Ylvisaker, M., & Feeney, T. (1998). Collaborative brain injury intervention: Positive everyday

routines. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group.

Ylvisaker, M., Szekeres, S., & Feeney, T. (1998). Cognitive rehabilitation: Executive

functions. In M. Ylvisaker (Ed.), Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: Children and

adolescents (2nd ed., pp. 221-269). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Sample Client (111) 27

04/14/2015

BRIEF

®

2 Teacher Form Item Response Table

Item

Response

Item

Response

Item

Response

1

Often

22

Sometimes

43

Sometimes

2

Sometimes

23

Sometimes

44

Sometimes

3

Often

24

Often

45

Sometimes

4

Often

25

Often

46

Sometimes

5

Sometimes

26

Sometimes

47

Sometimes

6

Sometimes

27

Sometimes

48

Often

7

Often

28

Often

49

Sometimes

8

Often

29

Sometimes

50

Often

9

Sometimes

30

Often

51

Never

10

Often

31

Sometimes

52

Sometimes

11

Sometimes

32

Often

53

Sometimes

12

Often

33

Often

54

Never

13

Often

34

Sometimes

55

Often

14

Sometimes

35

Often

56

Sometimes

15

Sometimes

36

Never

57

Never

16

Often

37

Sometimes

58

Often

17

Sometimes

38

Often

59

Often

18

Never

39

Often

60

Never

19

Often

40

Never

61

Sometimes

20

Often

41

Sometimes

62

Often

21

Sometimes

42

Often

63

Never

*** End of Report ***