TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 28 (2023): 19–41

19

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek

New Testament Manuscripts:

e Fragments

Zachary J. Cole, Reformed eological Seminary; Eunike C. Bentson, Tacoma, Washington;

and Randall M. Shandroski, Wyclie College, University of Toronto

Abstract: is study catalogs and categorizes the scribal corrections found in the ear-

liest fragmentary Greek New Testament manuscripts (second–fourth/h centuries).

Although corrections are normally identied and discussed by manuscript editors, this

analysis gathers such evidence from a wide range of artifacts in order to observe rele-

vant trends in scribal habits across the group as a whole. Corrections are identied in

the earliest 114 fragmentary manuscripts of the New Testament, including papyri and

parchment. ese corrections are then categorized and discussed, with attention given

to the copying process, text-critical evidence, and the identity of the correctors.

1. Introduction and Method

In recent years there have been numerous fruitful examinations of the scribal corrections

found in New Testament manuscripts, especially in the six largest papyri (P45, P46, P47, P66,

P72, and P75) and early majuscules.

1

Such studies have shed light on the following concerns:

scribal attitudes toward the text, the copying context, the transmission of the text, and the life

of a manuscript aer it was completed.

2

e present study seeks to analyze and draw obser-

We

would like to thank Peter Malik for his advice while we planned this project. We are grateful

also for the constructive suggestions made by the anonymous reviewer.

1

Notable is James R. Royse, Scribal Habits in Early Greek New Testament Papyri, NTTSD 36

(Leiden: Brill, 2008), who built upon the pioneering work of E. C. Colwell. On the corrections in

Codex Sinaiticus, see Dirk Jongkind, Scribal Habits of Codex Sinaiticus, TS 3.5 (Piscataway, NJ:

Gorgias, 2007), and more recently: Peter Malik, “e Earliest Corrections in Codex Sinaiticus: A

Test Case from the Gospel of Mark,” BASP 50 (2013): 207–54; Peter Malik, “e Earliest Correc-

tions in Codex Sinaiticus: Further Evidence from the Apocalypse,” TC 20 (2015): 1–12; and Peter

Malik, “e Corrections of Codex Sinaiticus and the Textual Transmission of Revelation: Joseph

Schmid Revisited,” NTS 61 (2015): 595–614. On Codex Bezae, see D. C. Parker, Codex Bezae: An

Early Christian Manuscript and Its Text (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). On Co-

dex Washingtonianus, see James R. Royse, “e Corrections in the Freer Gospels Codex,” in e

Freer Biblical Manuscripts: Fresh Studies of an American Treasure Trove, ed. Larry W. Hurtado,

TCS 6 (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2006), 185–226. On Codex Vaticanus, see Jesse

Grenz, “e Scribes and Correctors of Codex Vaticanus: A Study on the Codicology, Paleogra-

phy, and Text of B(03)” (PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 2021).

2

E.g., Larry W. Hurtado, e Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins

(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 186; Andrew Wilson, “Scribal Habits in Greek New Testament

Manuscripts,” Filología neotestamentaria 24 (2011): 95–126; Loretta H. Y. Man, “e Textual Sig-

nicance of Corrected Readings in the Evaluation of the External Evidence: Romans 5,1 as a Test

C a s e,” ZNW 107 (2016): 70–93; Katrin Maria Landefeld, “e Signicance of Corrections for the

Examination of the Emergence of Variants,” NTS 68 (2022): 418–30.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts20

vations from the scribal corrections found in the abundance of smaller, fragmentary New

Testament manuscripts.

It is, of course, true that manuscript editors usually (though not always) identify scribal

corrections where they appear in a given artifact, providing valuable insight into the work of

an individual scribe. As yet, though, there has been little by way of organized examination of

corrections across a wide range of witnesses. Other manuscript features have indeed been sub-

jected to broad-based studies, including features such as the nomina sacra, codex dimensions,

text divisions, and harmonization, for example, and with great benet.

3

Such analyses have

identied important trends and patterns across large bodies of material witnesses. By gath-

ering the evidence of corrections from a wide range of early manuscripts, this study seeks to

identify broader trends among early scribes, including questions about the overall frequency

of corrections, the kinds of corrections that scribes tended to make (or not), and the general

attitude that scribes had towards the text. e present study, therefore, will catalog and cate-

gorize the scribal corrections in all the early fragmentary manuscripts dated up through the

fourth/h century CE (second–fourth/h centuries), as a representative sample of scribal

behavior.

4

Given the amount of data under consideration here, our focus must necessarily be

restricted to a basic overview of the corrections from this period, with the hope that it will aid

future studies and investigations.

e exact denition of what constitutes a correction is not straightforward.

5

For the pur-

pose of this study, we include anything that appears to be an amendment to the text aer the

original act of writing, whether in the process of copying (in scribendo) or later, and those

by the original scribe or a later hand. Only corrections to the text are considered, not added

punctuation or diacritical marks. Corrections have been identied by examination of pub-

lished manuscript editions, including those in relevant editiones princepes and those available

on the INTF website.

6

Whenever possible, these were checked against manuscript images.

Close examination of the manuscripts led to the identication of some previously unnoticed

corrections.

3

On the nomina sacra, see Hurtado, Earliest Christian Artifacts, 95–134; on codex dimensions, see

Eric G. Turner, e Typology of the Early Codex (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1977); on text divisions, see Charles E. Hill, e First Chapters: Dividing the Text of Scripture in

Codex Vaticanus and Its Predecessors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022); on harmonization,

see Cambry Pardee, Scribal Harmonization in the Synoptic Gospels, NTTSD 60 (Leiden: Brill,

2019).

4

By “fragmentary” we mean all papyri (from II–IV/V, acc. to the Kurzgefasste Liste) except P45,

P46, P47, P66, P72, P75, and all majuscules from the same date range except 01, 03, and 032. For

studies of the corrections in these manuscripts, see note 1 above. e date range seeks to include

as many witnesses as possible while remaining manageable.

5

See the methodological discussion in Royse, Scribal Habits, 74–79, and the extensive bibliographic

footnote in Peter Malik, P.Beatty III (P47): e Codex, Its Scribe, and Its Text, NTTSD 52 (Leiden:

Brill, 2017), 72 n. 5.

6

For bibliographic information regarding editiones princepes, see the Liste and J. K. Elliott, ed., A

Bibliography of Greek New Testament Manuscripts, 3rd ed., NovTSup 160 (Leiden: Brill, 2015).

Other transcriptions were consulted occasionally, such as Lincoln H. Blumell and omas A.

Wayment, eds., Christian Oxyrhynchus: Texts, Documents, and Sources (Waco, TX: Baylor Uni-

versity Press, 2015), and Philip W. Comfort and David P. Barrett, eds., e Text of the Earliest New

Testament Greek Manuscripts, 2nd. ed. (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 2001). Note, however, that

the most recent third edition of Comfort and Barrett (Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic, 2019) has

removed the majority of notes related to scribal corrections included in the rst two editions.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 21

Of the 114 manuscripts under examination, 70 lack any extant corrections: P1, P7, P8, P9,

P10, P12, P22, P24, P25, P28, P29, P30, P32, P35, P39, P49,

7

P52, P57, P62, P64+67,

8

P65, P71, P78,

P80, P82, P85, P87, P89, P90, P91, P95, P98, P101, P102, P104, P107, P108, P109, P111, P113, P114,

P119, P120, P121, P122, P123, P125, P126, P133, P134, P137, 058, 0160, 0162, 0181, 0185, 0188, 0189,

0206, 0207, 0214, 0219, 0221, 0228, 0230, 0231, 0258, 0308, 0312, and 0315.

irty-seven of the manuscripts have at least one clear instance of a correction: P4, P5, P6,

P13, P15, P17, P18, P19, P20, P23, P27, P37, P40, P48, P50, P53, P70, P77,

9

P81, P86, P88, P92,

P100, P103, P106, P110, P115, P117, P118, P139, P141, 059+0215, 0169, 0171, 0220, 0242, and 0270.

e remaining seven have possible instances of corrections, but for reasons enumerated

below there is some uncertainty about them: P16, P21, P38, P69, P132, P138, and 057.

In the following sections, these corrections are presented by category of error, adapting the

categories used by James Royse and others: orthography, strictly nonsense, nonsense in con-

text, omissions, additions, substitutions, transpositions, and those that cannot be categorized

with certainty.

10

By strictly nonsense we mean readings that are nonsensical words or fragments

of words.

11

Nonsense in context denotes a proper Greek word or phrase that is incomprehen-

sible in its context. Readings are classied under orthography if the correction applies to a

vocalic or consonantal interchange known from the Koine period.

12

Given the diculties involved in identifying the hand responsible for a correction, it is

assumed that corrections are by the original scribe unless editors have explicitly suggested

otherwise (rsthand corrections indicated by

c

, secondhand by

2c

, third by

3c

). Attention is also

given to the possibility that a correction was made in scribendo, that is, while in the process of

copying.

13

Where these can be identied with some condence, they are highlighted. Relevant

text-critical information is also provided for each variation unit, although for the purpose of

this analysis such information has been kept to a minimum and restricted to Greek evidence

only.

14

When multiple corrections occur within a single verse, these are distinguished by an

accompanying letter (a, b, c, etc.) according to their order of treatment (e.g., Matt 1:1a).

7

It is possible that P49 and P65 belong to the same original codex.

8

It is possible that P4 and P64+67 belong to the same original codex.

9

It is possible that P77 and P103 belong to the same original codex.

10

Royse, Scribal Habits, 74–79.

11

Following E. C. Colwell, “Method in Evaluating Scribal Habits: A Study of P45, P66, and P75,” in

Studies in Methodology in Textual Criticism of the New Testament, NTTS 9 (Leiden: Brill, 1969),

106–24 (111), “e Nonsense Readings include words unknown to grammar or lexicon, words

that cannot be construed syntactically, or words that do not make sense in the context,” and

also Royse, who further distinguishes between strictly nonsense and nonsense in context (Royse,

Scribal Habits, 91).

12

According to Francis T. Gignac, A Grammar of the Greek Papyri of the Roman and Byzantine

Periods, Testi e documenti per lo studio dell’antichità 55, 2 vols. (Milan: Istituto Editoriale Cisal-

pino-La Goliardica, 1976–1981). On linguistic interchanges in recent study, see Mark Depauw and

Joanne Stolk, “Linguistic Variation in Greek Papyri: Towards a New Tool for Quantitative Study,”

GRBS 55 (2015): 196–220.

13

On which, see Royse, Scribal Habits, 115 n. 65.

14

e following apparatuses were used to obtain text-critical evidence: NA28; UBS5; Kurt Aland’s

Synopsis; Tischendorf’s Editio Octava Critica Major; Reuben Swanson’s volumes of Matthew,

Mark, Luke, John, Acts, and Romans; the IGNTP volumes of the Gospel according to Luke; the

ECM volumes of Mark, Acts, and the Catholic Epistles; and the critical edition of Hermann von

Soden. Due to the degree of error observed in von Soden’s apparatus, as a rule we have not listed

witnesses cited by him alone unless they could be conrmed by a photograph or transcription.

For the book of Revelation, Herman Hoskier’s collations were also consulted. Solus indicates

that, as far as can be established, the reading in question is found in no other Greek witnesses.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts22

Two sections (§§10–11) at the end provide summaries of the corrections that are identied

as in scribendo and those that are from a later hand, followed by a nal section with summative

and concluding observations (§12).

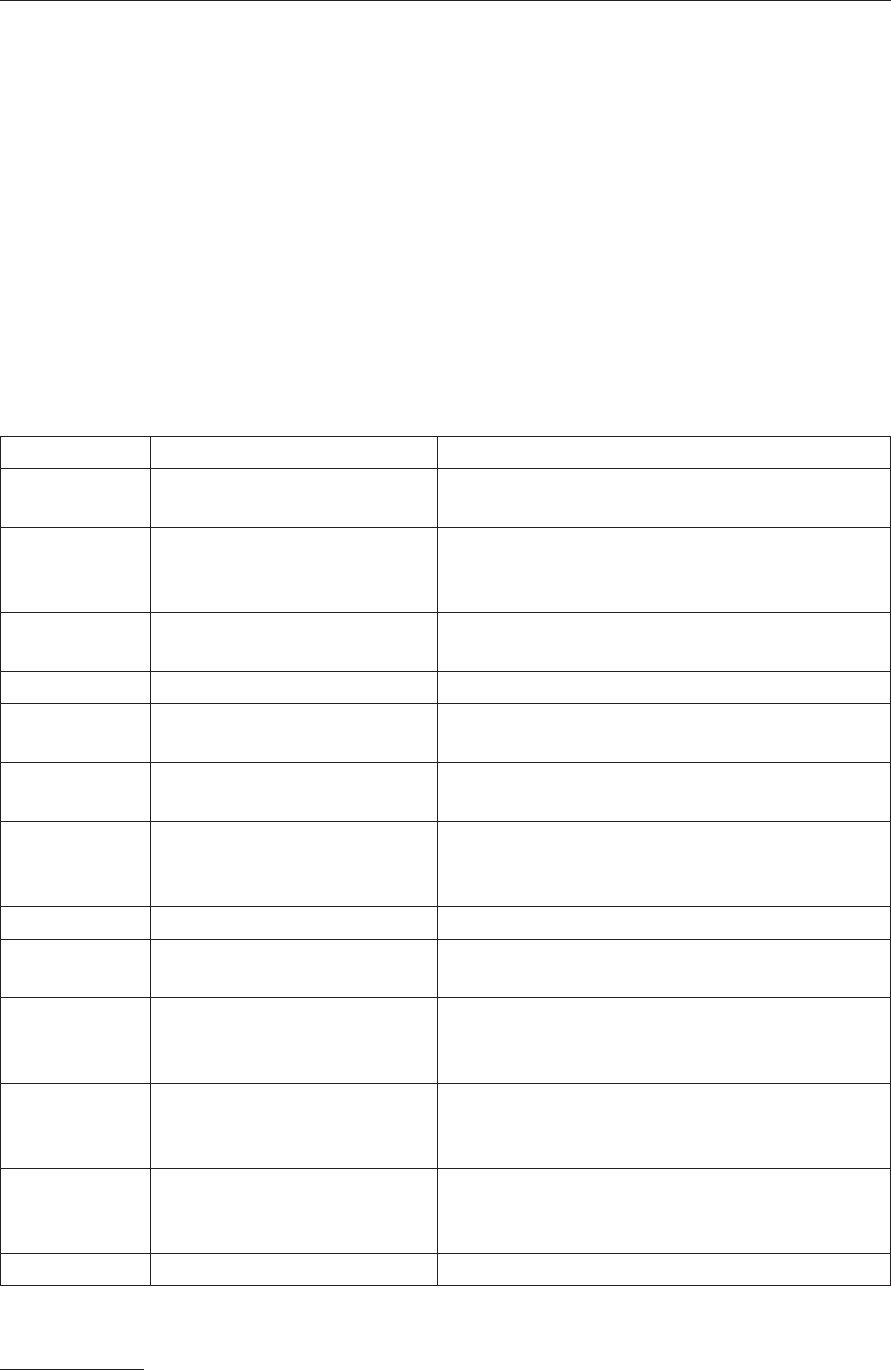

2. Orthography

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 5:24

15

οφεϲ P86* solus αφεϲ P86

c

rell

Matt 10:25a

16

βεελϲεβου̣λ̣ P110* solus βεελζεβου̣λ̣ P110

c

rell

(βεεζβουλ 349 | βεεζεβουλ 01 03 | βελζεβουλ

05 019 033 16 566* 1093*)

Matt 23:37a

17

[ηθ]ελεικα P77* solus [ηθ]εληκα P77

c

solus

(ηθεληϲα rell | ηθελιϲα 346 579 1346)

Matt 26:28

18

[εκ]χυνομενον P37* rell [εκ]χυννομενον P37

2c

01 02 03 04 05 019 035

037 038 041* 042 043 047 064 1 33 174* 489

1010 1219 1293 1295 1582*

Luke 3:29

P4* solus? ιηϲου P4

c

01 03 019 038 0124 f

13

33 69 346 543

788 826 983 1241 1604

(ιωϲη rell | ιεη 1192 | ιεϲη 22 1005 1210 1365 2372

| ιηϲω 036 f

1

1582* 2193 | ιοϲη 1685 | ιωϲηχ 033

213 892 1342 | ιωϲτη 273 | ιωϲϲη 1542 | om. του

ιηϲου 157 2757)

John 16:20

19

λοιπηθ̣η|[ϲεϲθε] P5* solus λυπηθ̣η|[ϲεϲθε] P5

c

rell

(λυπηθηϲεϲθαι 01 02 032 2* 33 579 1071 1235 |

λυπηϲεϲθε 022* | λυπιθησεσθαι 047)

John 16:21

λοι|[πην] P5* solus λυ̣|[πην] P5

c

rell

Acts 8:32a

20

αναγινωϲ|κεν P50* solus ανεγινωϲ|κεν P50

c

rell

(ανεγεινωϲκεν 03 | ανεγιγνωκϲεν 2243)

Rell indicates the remaining Greek manuscripts not explicitly cited, but some variants have been

ignored when they are irrelevant to the issue at hand.

15

On the interchange of α and ο, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:286–88, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 895.

16

On the interchange of ζ and ϲ, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:120–24, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 888. It

is worth mentioning that P110 uses an apostrophe in the word: βεελ'ϲεβου̣λ̣. Note also that NA28

(misleadingly) lists 05 and 019 in support of βεελζεβουλ.

17

On the interchange of η and ει, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:239–42, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 893.

e ed. princ. registers some doubt about the originally written text, but we are persuaded the

INTF transcription is correct with ει. In addition, since the beginning of the word [ηθ]εληκα must

be reconstructed, it is possible that a dierent form of the verb was written here. However, since

there are no other known variants in the verb form, we have followed the ed. princ. and INTF

transcription.

18

On the interchange of ν and νν, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:158, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 890. e

second hand is suggested by Henry Sanders in the ed. princ., but see Tommy Wasserman, “e

Early Text of Matthew,” in e Early Text of the New Testament, ed. Charles E. Hill and Michael J.

Kruger (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 83–107 (91), who suggests rst hand.

19

On the interchange of υ and οι, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:198–99, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 892.

20

On the interchange of ε and α, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:283, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 894.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 23

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Rom 5:3

21

[θ]λειψιϲ 0220* [θ]λιψιϲ 0220

2c

rell

(θληψειϲ 2147 | θληψηϲ 1243 | θληψιϲ 33 618

1646 2464 | θλιψειϲ 02 06 010 012)

Rom 6:15

22

[εϲμ]ε P40* solus [εϲμ]εν P40

c

rell

Rom 16:12

23

[τ]ρ̣υ̣φαναν P118* [τ]ρ̣υ̣φαιναν P118

c

rell

(τρυφεναν 01 02 010 012 025 326 1243 1837

2464 | τρυφηναν 1874

c

| τυφαιναν 04*)

1 Cor 7:23a

γινεϲθε P15* rell γεινεϲθε P15

c

P46 01 03*

(γεινεϲθαι 02 06* | γινεϲθαι 06

c

010 012 69* 88

131 218 440 460 1243 1646 1175 1735 1881

c

2125

2464 | γενηϲθε 330 2400)

Heb 3:6

24

χαυχη|[μα] P13* solus καυχη|[μα] P13

c

rell

Heb 3:10

25

προϲωκτειϲα P13* solus προϲωκθειϲα P13

c

solus

(προϲωχθιϲα rell | προϲοχθηϲα 131 1243 1735

1962 | προϲωχθειϲα 02 | προϲωχθηϲα 020 025

33 81 88 181 218 999 1245 1315 1424 1646 1751

1836 1874 1881 1891 1908 1912 | προϲωχθηϲαν

1319 2464 | προϲωχθητι 1573)

Heb 10:11

λιτου[ργων] P13* 01 06 λειτου[ργων] P13

c

rell (om. 2464)

Heb 11:3

26

φενομεν̣ων P13* 1243 1735 φα̣ι̣νoμεν̣ων P13

c

rell

(φαινωμενων 1319 | φαιν 01* | φενωμενον 1751)

Heb 11:32

27

δαυιδ P13* 06

c

0319 945 pm δαυειδ P13

c

P46 01 06*

( 02 018 020 025 pm | δαβιδ 1 al)

Heb 12:11a

28

[ι]ρηνικον P13* 01 ειρηνικον P13

c

rell

(ειρηνηκον 1 1243 | ειρινικον 1751)

21

On the interchange of ει and ι, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:189–90, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 892;

more recently, Joanne Vera Stolk, “Itacism from Zenon to Dioscorus: Scribal Corrections of <ι>

and <ει> in Greek Documentary Papyri,” in Proceedings of the 28th Congress of Papyrology, Barce-

lona 1–6 August 2016, ed. Alberto Nodar and Sofía Torallas Tovar, Scripta Orientalia 3 (Barcelona:

Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat 2019), 690–97.

22

On the omission of nal nu, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:111–12, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 887–88.

e correction in P40 at Rom 6:15 is located in fragment f, according to identications made by

Philip W. Comfort, “New Reconstructions and Identications of New Testament Papyri,” NovT

41 (1999): 214–30 (220–21). e correction itself is noted in Comfort and Barrett, e Text of the

Earliest (2nd ed.), but the images on NTVMR are not clear at this point.

23

On the interchange of αι and α, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:194, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 892.

24

On the interchange of κ and χ in the initial position, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:91–92, and Royse,

Scribal Habits, 887. Although the χ was overwritten with κ by the scribe of P13, the identication

is very likely. Note that the INTF transcription does not record many of the corrections recorded

in the ed. princ.

25

On the interchange of θ and τ, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:92, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 887.

26

On the interchange of αι and ε, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:192–93, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 892.

27

BDAG (s.v. “Δαυίδ, ὁ”) lists δαυειδ as an alternate spelling of δαυιδ. On the nomen sacrum form

more generally, see Ludwig Traube, Nomina Sacra: Versuch einer Geschichte der christlichen

Kürzung (Munich: Beck, 1907), 104–5.

28

Although the initial iota in [ι]ρηνικον in P13* (at Heb 12:11a) is no longer visible, there is no real

doubt about what letter stands beneath the correction ει-.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts24

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

James 1:10

29

ταπεινουϲι P23* solus ταπεινωϲι P23

c

03

(ταπεινωϲει rell | ταπινωϲει P74 01 | πιϲτει 614)

James 1:11a

30

καυϲο̣νει P23* solus καυϲωνει P23

c

(καυϲωνι rell)

Rev 8:7

31

[το] P115* 1719 [το] τριτ̣ο̣[ν]

2

P115

2c

pm

(το τριτω 2067 | το τριτων 1617 | τω τριτω 2051)

e orthographical corrections made in our manuscripts reect interchanges that were com-

mon in extrabiblical papyri, as indicated by the references to Francis Gignac’s grammar and

Royse’s study. Most of the errors involve phonetic confusion, and the majority of these involve

vowels. Some of these slips could perhaps involve visual confusion as well: for example, νν > ν

(Matt 26:28), κ > χ (Heb 3:6). ere is one instance of an omitted nal nu (Rom 6:15).

Two of the corrections relate to the use of abbreviations. At Luke 3:29, the scribe of P4

appears to have initially written the nomen sacrum and then changed it to the plene form

ιηϲου. Perhaps the full form was preferred because in this instance ιηϲου refers to Joshua rather

than Jesus.

32

e spacing suggests that this correction was made in scribendo.

Similarly, the last correction listed in this section (Rev 8:7 in P115) was made by a later hand

adjusting the form of a numeral. Whereas the original scribe used the shorthand in place

of the ordinal number τριτον, a later hand corrected it to the longhand form while preserving

the same value. Presumably this correction was made because numerical shorthand is unusual

for ordinal numbers in New Testament manuscripts and is potentially confusing to a reader,

since it obscures the case ending.

33

ere is another possible instance of this sort of correction

in P115 (see below).

Two other corrections appear to have been made in scribendo. In both P15 (1 Cor 7:23a) and

P50 (Acts 8:32a), the spacing of the letters suggests that the errors were caught and corrected

before the scribes continued to the following word.

ree additional instances of orthographical corrections are possible but uncertain due to

partial illegibility.

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Acts 23:27a

34

ϲυ[λ?]λημφθεντα P48* P74 01

02 03* 642 1175 2200

vid

ϲυνλημφθεντα P48

c

08

(ϲυηφθεντα rell | ϲυνληφθεντα 1884)

1 Cor 7:23b

[?] P15* P15

c

Rev 14:20

P115* solus? (cf. 1854) ⁰? P115

2c

[= διϲχιλιων εξακοϲιων 1854]

(“εν αλ ,β” 456

mg

| , rell [= χιλιων εξακοϲιων]

| χιλιων 1719 | , 1876 2014 2034 2036 2042

2043 2047 2074 2082 [= χιλιων εξακοϲιων εξ

2037 2046] | εξακοϲιων 2065

txt

| χιλιων 04

c vid

|

χιλιων διακοϲιων 01* 203 506)

29

On the interchange of ω and ου, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:209–11, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 892.

30

On the interchange of ω and ο, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:275–77, and Royse, Scribal Habits, 894.

31

Transcriptions of the text here vary in their details but agree in essence (cf. ed. princ., INTF,

ISBTF, Parker).

32

See Tommy Wasserman, “A Comparative Analysis of P4 and P64+67,” TC 15 (2010): 1–26 (7 n. 31).

33

See Zachary J. Cole, Numerals in Early New Testament Greek Manuscripts: Text-Critical, Scribal,

and eological Studies, NTTSD 53 (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 206–10.

34

On the assimilation of ν and liquids, see Gignac, Grammar, 1:169–170.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 25

In the case of Acts 23:27a in P48, it is possible that the rst nu of ϲυνλημφθεντα was writ-

ten over an initial lambda, but this is now unclear. Similarly, at 1 Cor 7:23b in P15, the scribe

appears to have begun writing ανθρωπων in full, as the now-eaced letter strongly resembles

a theta (so ed. princ.), but caught it immediately and corrected the text to the nomen sacrum

. If so, this correction would be another instance of one made in scribendo.

Similar to Rev 8:7 above, it appears that another numeral in P115 was altered, this time at

Rev 14:20, where the scribe originally wrote . is, too, is an ambiguously written numeral.

When standing for two thousand (as it presumably is here), the letter beta normally has either

a surmounting curl or a preceding diagonal stroke. us, the faint loop added to the top le of

the beta might be an attempt to clarify the meaning of the numeral, but, because of the faded

state of the ink, it is dicult to be certain.

35

3. Strictly Nonsense

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Mark 2:19

νανται P88* solus δυνανται

2

P88

3c

pm

(δυναντε 579 1579 l2211 | δυναται 728 1005*)

Mark 2:23

ϲ̣π̣ο̣ριων̣ P88* solus ϲ̣π̣ο̣ριμων̣ P88

c

rell

(εϲπαρμενων 032 | ϲπορμων 037 | ϲποριμον 117* |

ϲπορημων 740 752 983 1009 1029 | ποριμων l2211)

Luke 22:45

κοιμενουϲ 0171* solus κοιμωμενουϲ 0171

2c

rell

(κοιμουμενουϲ 022*)

John 1:33

μι P106* solus μοι P106

c

rell

John 11:2

ται P6* solus ταιϲ P6

c

rell

(τεϲ 038)

Acts 10:30a

τ P50* solus νηϲτ[ε]υ̣ων P50

c

02

c

05 08 020 044 33 104 614 1175

1241 1505 1884 2147 2495 2818 al

Acts 10:31a

προϲευε̣ P50* solus προϲευχη P50

c

rell

(αι προϲευχαι 1890 | ευχη P45 | δεηϲια 1829 | δεηϲιϲ

228 996 1243)

Acts 10:31b

ενωπ̣ι̣ου P50* solus ενωπ̣ι̣ον P50

c

rell

2 Cor 7:7

περ P117* solus υπερ P117

c

rell

(om. υπερ μου 018)

Heb 4:11

πετη P13* solus πεϲη P13

c

rell

(περιπεϲη 256 | πεϲει 025 131 1319 1735 2464 | om.

1573)

James 3:5

μ[ε]γαυ̣αυχει P20* solus μεγαλ̣αυχει P20

c

rell

(μεγαλα αυχει P74 02 03 04* 025 33

vid

43 81 330 400

1243 1270 1297 1390 1595 1598 1893 2344 l884)

James 3:14

ψεδε̣υ|[ϲθε] P100* solus ψευε̣υ|[ϲθε] P100

c

solus

(ψευδεϲθε rell | ψευδεϲθαι 01 33 1243 1751 1874

c

|

καταψευδεϲθε 1840 | om. και ψευδεϲθε l427)

Rev 11:18

[διαφθειρ]ονα̣ϲ̣ P115* solus [διαφθειρ]οντ̣α̣ϲ̣ P115

c

pm

35

Cf. David C. Parker, “A New Oxyrhynchus Papyrus of Revelation: P115 (P. Oxy. 4499),” NTS 46

(2000): 159–74 (164). It is unclear how the ISBTF transcription arrived at for P115

c

.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts26

Scribes created nonsense readings through a variety of means. Out of these thirteen errors, ve

result from the omission of a single letter (Mark 2:23; John 1:33; 11:2; 2 Cor 7:7; Rev 11:18), and

two result from the loss of two letters (Mark 2:19; Luke 22:45). Two errors involve the confu-

sion of letters (Acts 10:31b; Heb 4:11).

e correction in P106 at John 1:33 is worth highlighting because it appears to have been

made in scribendo. Note that, aer writing the mu of μοι, the scribe wrongly wrote iota but cor-

rected it to omicron with plenty of space to write iota again before the following word (ειπεν).

We can suggest causes for a few of these errors. For instance, the loss of δυ- from δυνανται

in Mark 2:19 (P88*) might have been prompted by parablepsis with the immediately preceding

ου. In addition, the confusion of letters at Heb 4:11 in P13 could have been a visual error: ϲ > τ,

as could have been the error ν > υ in P50 at Acts 10:31b.

e remaining four nonsense readings are more challenging to explain. e error at Acts

10:30a in P50 might represent an erroneous leap forward. e editor suggests that, aer writ-

ing ημην, the scribe began to write την εννατην (which would have omitted νηϲτευων και or

transposed it) but immediately corrected himself.

36

Similarly, in writing προϲευε̣ for προϲευχη

(Acts 10:31a), the scribe might have leapt to ϲου εμνηϲ- in the following line and xed it before

continuing, but this is just one possibility.

37

e precise reading of P100 at Jas 3:14 is dicult to discern. In any case, it is clear that the

scribe wrote a nonsense word and failed in the attempt to correct it clearly.

38

e same is true of

P20 at Jas 3:5. Although the correction has partially eaced the initially written text, the scribe

has apparently attempted to rectify a nonsense word.

39

In addition, three more nonsense corrections are possible but uncertain due to partial

illegibility.

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 10:26

β̣? P110* solus

om. P110

c

rell

Luke 3:27

ου [υ?]ηϲαυ P4* solus ου ρ̣ηϲαυ P4

c

solus

(ρηϲα rell | ραϲα f

13

| ρηϲϲα 69 700 713 2542 | ριϲα

179 l1056 | ϲηρα 1604)

Acts 18:27

40

τ[ι?]ν P38* solus την P38

c

rell

36

Alternatively, the copyist might have leapt to the tau in νηϲτευων.

37

e editor suggests the overwritten letter was sigma rather than epsilon (so INTF); either way, the

reading is nonsense.

38

Here we follow the INTF transcription; but cf. ed. princ.: “ψευ̣δευ: half-formed υ and δ apparently

run together, with supralinear dot over δ. e scribe may have written ψεδευ by mistake, then

attempted to insert υ aer the rst ε, signalling the error with a dot over the δ. In which case he

failed to delete the superuous υ.” Either way, the original reading classies as a nonsense error.

39

Here we depart from the transcription of the ed. princ. and INTF in favor of the reading oered

by J. K. Elliott, “e Early Text of the Catholic Epistles,” in Hill and Kruger, Early Text of the New

Testament, 204–24 (213 n. 29): “P20 reads μεγαυαυχει in which λ replaced υ

1

as a correction; this λ

was then understood in the ed. pr. to be a ligature of λα.” See also Blumell and Wayment, Christian

Oxyrhynchus, 87, who suggest that the scribe rst wrote μεγαλαυ and then corrected the reading

to μεγαλα αυχει, with the resulting restoration: μεγαλ[[α]]`α`υχει. Both proposals would classify

as strictly nonsense.

40

Compare Sanders’s rst transcription in the ed. princ., where he reads […]θε̣ι ̣ν̣ and calls it “doubt-

ful,” with his later judgment about the same reading (P.Mich. 3.138): “την was corrected from τιν

in slightly lighter ink or the cross line has faded more on this decayed margin.” We opt for his

latter opinion here. Note that INTF has τη at this point. Tischendorf also lists “12lect” in support

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 27

In P110 at Matt 10:26, the ed. princ. suggests that between ουν and φ[οβηθητε] stands a can-

celed beta. Clearly there is a stroke of ink. However, since we are unable to identify the stroke

as a beta or a part of one, we list it here as a possibility. e remaining two possible errors

involve the substitution of erroneous letters (Luke 3:27; Acts 18:27), but they are no longer

suciently legible.

4. Nonsense in Context

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 10:25b

[τοιϲ?]| οικιοιϲ P110* solus [τουϲ]| οικιουϲ P110

c

solus

(τουϲ οικιακουϲ rell | τοιϲ οικιακοιϲ 03* | τουϲ

οικειακουϲ 04 05 021 030 032 034 f

1

22 35 157 270

280 473 1005 1071 1582 2372 al)

Matt 26:26

εκαλεϲεν P37* solus εκλαϲεν P37

c

rell

(εκλαϲε 034 f

13

35 69 118 157 700 788 1005

c

1346

2372)

Mark 2:10

ε̣[χ]ε̣ P88* ε̣[χ]ε̣ι P88

2c

rell

(εχη 07 | εχι 01)

Luke 5:36

παλαι|ου P4* 827 2643 κα̣ιν̣|ου̣

1

P4

c

rell

(κενου 69*)

Acts 8:32b

τον P50* solus του P50

c

rell

Acts 10:28a

41

ιουδαιου P50* solus ιουδαιω P50

c

rell

Acts 10:28b

κ̣ο̣ινοι P50* solus κ̣ο̣ινον P50

c

rell

(κυνον 81)

Acts 10:30b

τη P50* ταυτηϲ P50

c

pm

Heb 10:16

[α]υτ̣ων α̣ P13* solus [α]υτ̣ων

2

P13

c

rell

Heb 10:19

εχοντα̣ϲ P13* solus εχοντε̣ϲ P13

c

rell

Heb 12:11b

42

αυτοι ̣ϲ P13* 06 1 1319c 1912 1962 αυτηϲ P13

c

rell

(αυτου 1315)

1 Pet 3:10

τη P81* P72 την̣ P81

c

rell

Rev 3:12

[του ν]α̣ου P115* solus [τω ν]α̣ω P115

c

rell

(το ναον 2087 | τω οικω 1006 1841 | τω ονοματι

911 920 1859 2027)

Several copyists wrote identiable Greek words that happen to be nonsense in their particular

contexts. Of these thirteen errors, three could simply be orthographical slips (Mark 2:10; Heb

10:19; 1 Pet 3:10), but they have in any case resulted in nonsense in their contexts. Additionally,

three readings could be the result of visual confusion (all in P50): του > τον; ιουδαιω > ιουδαιου;

and κ̣ο̣ινον > κ̣ο̣ινοι (Acts 8:32b; 10:28a, 28b). Regarding the latter correction in particular, spac-

of τη. However, if “12lect” is equivalent to l60 (cf. Caspar R. Gregory, Textkritik des neuen Tes-

taments, 3 vols. [Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1900–1909], 1:393, 465), then this would seem to be an error.

41

e precise reading here is uncertain. e ed. princ. suggests that the scribe rst (correctly) wrote

ιουδαιω, then (wrongly) corrected it to ιουδαιου, and then (re)corrected to the original ιουδαιω.

Above we list it as presented by the INTF transcription.

42

e ed. princ. notes that the underlying letter(s) here could be either ο or οι. We have followed

the INTF transcription here in printing αυτοι ̣ϲ. Either way, the reading would be nonsense in its

context.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts28

ing suggests that κ̣ο̣ινοι was corrected to κ̣ο̣ινον before the scribe copied the following words (η

ακαθαρ|τον).

ree instances result from harmonization to the immediate context. e substitution

of παλαιου for καινου by the scribe of P4 (Luke 5:36) is probably due to the frequent use of

the word in the context (5:36, 37, 39). At Heb 12:11b, the scribe of P13 originally wrote τοιϲ δι

αυτοι̣ϲ γεγυμναϲμενοιϲ instead of τοιϲ δι αυτηϲ γεγυμναϲμενοιϲ. e erroneous [του ν]α̣ου in

P115 (Rev 3:12) might be a harmonization to the immediately following phrase: του θεου. One

error appears to be a nonsensical harmonization either to the wider context or more familiar

wording: P37 at Matt 26:26 (cf. ἐκάλεϲεν in 25:14).

Regarding Matt 10:25b in P110, the editor suggests that, while it is possible that οικιοιϲ has

been corrected to οικιουϲ, it is more likely that the upsilon was simply reinked. We have decided

to retain it here as a correction because the shape of the originally written letter more closely

resembles iota rather than upsilon, suggesting that it is indeed a corrected error.

43

Although the superuous alpha in P13 at Heb 10:16 could be considered strictly nonsense,

it is listed here as nonsense in context because it could be understood as a word (e.g., relative

pronoun). It was the result of a leap from αυτων either to αυτουϲ (thereby omitting επιγραψω)

or, more likely, to των αμαρτιων or των ανομιων (10:17).

44

Either way, the scribe immediately

caught the error and canceled it. Similarly, the erroneous τη in P50 (Acts 10:30b) appears to be

a leap over the ταυ- in ταυτηϲ that the scribe caught immediately.

One more correction possibly ts in this category but cannot be conrmed due to partial

illegibility.

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Mark 2:25

ο̣υ̣? P88* solus οι̣ P88

3c

rell

According to the ed. princ. and INTF transcription, the scribe of P88 (at Mark 2:25) wrongly

wrote και ου, which was subsequently corrected to και οι̣. e IGNTP transcription, however,

notes that this is possible but uncertain due to the poor state of the papyrus.

5. Omissions

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 5:13 om. P86* 01 03 04 f

1

33 205 892

και P86

2c

rell

Matt 13:35 om. 0242* solus

[εν πα]|ραβολαιϲ το ϲτομα̣ [μου ερευξομαι]

0242

c

rell

Matt 13:56 om. P103* solus

[ει]ϲιν P103

2c

rell

(ειϲι 021 028 030 034 036 f

1

118 157 700

c

1071)

Matt 23:37b

45

om. P77* solus

και

2

P77

2c

rell

43

Note, for example, how other upsilons in P110 have a leward tail at the very bottom (e.g., ↓ ll. 1,

2, 4, 5; → ll. 3, 5, 6, 8) while the iotas lack it (↓ ll. 2, 5; → l. 6), as here. (Line numbers here follow

those of the INTF transcription rather than the ed. princ.) Note also that a similar correction was

made in Codex Vaticanus at this very point: τοιϲ οικιακοιϲ (03*), τουϲ οικιακουϲ (03

c

).

44

Ed. princ.: “e scribe apparently began to write αυτουϲ before επιγραψω, but that the α was

meant to be deleted is not certain and its partial eacement may be accidental.”

45

e ed. princ. identies this as a correction from a second hand, but see Wasserman, “e Early

Text of Matthew,” 98, and Peter Head, “Some Recently Published NT Papyri from Oxyrhynchus:

An Overview and Preliminary Assessment,” TynBul 51 (2000): 1–16 (7), both of whom identify it

as rsthand.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 29

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 24:14

46

[το | ευαγ]γ

̣

ελιο̣ν P70* 036 043

047 22 245 251 280 1012 1194

1295 1402 1574

[το | ευαγ]γ

̣

ελιο̣ν το̣υτο P70

2c

05 (579) 1223

(τουτο το ευαελιον rell)

Matt 26:29

47

om. P37* 01* 04 019

του P37

2c

rell

(om. τουτου 037 043 124 157 174

c

485 892 983

1010 1375 1424 1579 1689)

Matt 26:39a

48

om. P53* 019 037 042 f

1

205 892

2542

μου P53

2c

rell

Matt 26:49–50 om. P37* solus

δ̣ε̣ ο P37

c

solus

49

(χαιρει ραββι και κατεφιληϲεν αυτον ο δε

ειπεν pm)

Mark 15:32

αυτω 059+0215* rell ϲυν αυτω 059+0215

c

01 03 019 038 083 0184

79 372 472 517 579 713 780 892 949 1675 2427

2737

(om. 05 706 792 803 827 1029* 1241 1326 1402

1424 1446 1593 2542

s

1241 | μετ αυτου 044)

Luke 2:42

αυτω P141* solus αυτω ετη P141

c

05 019 579

(ετων rell | ετη 273)

John 1:38a om. P5* solus

οι δε P5

c

rell

(ο δε 579)

John 16:19 om. P5* 03 019 032 1071 ο P5

c

rell

John 16:23–24

50

[δωϲει υμειν] | om. P5* solus [δωϲει υμειν] | εν τω ονοματι [μου εωϲ αρ]τ[ι

ουκ ητηϲατε ουδεν] P5

2c?

01 03 04* 019 033 037

054 l844

(εν τω ονοματι μου δωϲει υμιν εωϲ αρτι ουκ

ητηϲατε ουδεν rell | δωϲει υμιν εωϲ αρτι ουκ

ητηϲατε ουδεν 118 205 209)

John 16:29

51

om. P5* 01 03 04* 022 038 039

041 044 0211 0250 1 157 262 489*

565 1187 1219 1342 1582* 2145

2193

[αυ]τ̣ω̣ P5

c

rell

(om. αὐτω οἱ 1321*)

46

e ed. princ. identies this as a correction from the rst hand, but Wasserman attributes it to a

second hand: Wasserman, “Early Text of Matthew,” 97.

47

e ed. princ. identies this as a correction from a second hand, but Wasserman attributes it to

the rst hand: Wasserman, “Early Text of Matthew,” 91.

48

Ed. princ.: “e added μου is by a dierent hand but probably contemporary.”

49

Although we have followed INTF here in reading the interlinear correction as δ̣ε̣ ο , the reading

is not certain. For more on this variation unit, see note below.

50

ere is some uncertainty here due to manuscript damage, but it is clear that the omission has

been restored (at least partially) in the bottom margin. Given the line length, it is more likely that

P5 followed 01 and 03 (etc.) in having δωϲει υμιν (or υμειν) prior to εν τω ονοματι μου (16:23) rath-

er than the majority of witnesses, which have it aer. Also, there are few dierent ways to restore

the text of the marginal correction; cf. ed. princ., INTF, IGNTP, and Comfort and Barrett (INTF is

followed above). For further discussion, see Peter M. Head, “e Habits of New Testament Copy-

ists: Singular Readings in the Early Fragmentary Papyri of John,” Bib 85 (2004): 399–408 (404),

and Lonnie D. Bell, e Early Textual Transmission of John: Stability and Fluidity in Its Second and

ird Century Greek Manuscripts, NTTSD 54 (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 119.

51

e NA28 apparatus appears to be in error here regarding the wording of 01 (John 16:29).

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts30

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

John 20:19 om. P5* solus

και

3

P5

c

rell

Acts 9:35 om. P53* 01*

τ[ον]

1

P53

c

rell

(την ϲαρρωναν l1188 | om. και τον ϲαρωναν

1642*)

1 Cor 15:10a

[η χ]α̣ριϲ ϲυν̣ εμοι 0270* solus [η χ]α̣ριϲ [του] ̣̣ ϲυν̣ εμοι 0270

2c

01* 03 06*

010 012 0243 6 1738 1739

(η χαριϲ του η ϲυν εμοι rell | η χαριϲ η ϲυν

εμοι 1611 1505 2495 | η χαριϲ του η ειϲ εμε

P46 | η χαριϲ αυτου η ϲυν εμοι 2143)

1 Cor 15:10b

[η χ]α̣ριϲ [του] ̣̣ ϲυν̣ εμοι

0270

c2

01* 03 06* 010 012 0243

6 1738 1739

[η χ]α̣ριϲ [του] ̣̣ η ϲυν̣ εμοι 0270

3c

rell

(η χαριϲ η ϲυν εμοι 1611 1505 2495 | η χαριϲ του

η ειϲ εμε P46 | η χαριϲ αυτου η ϲυν εμοι

2143)

Eph 1:11

52

om. P92* 044 263 1319 1573 2127

κ̣αι P92

c

rell

James 1:11b om. P23* 1890 2138

και

3

P23

c

rell

Rev 3:20

53

om. 0169* 1704 1852 2196

κρ̣ο̣υω ε[α]ν̣ τ[ιϲ] α̣κ̣ου[ϲη τηϲ | φωνη]ϲ μ[ου

και ανοιξη την θυραν και]

54

0169

c

rell

Rev 3:21a om. 0169* solus

[μ]ου 0169

2c

rell

Rev 4:3 om. 0169* rell

επι τον θρ̣[ονον] 0169

2c

solus

Rev 13:3 om. P115* rell

ε̣κ P115

c

01 02 04 046

c

025

Rev 14:15 om. P115* solus

η P115

2c

rell

As is evident, our copyists were especially prone to the omission of verba minora: conjunc-

tions, pronouns, articles, particles, prepositions, and the like. Of the twenty-ve corrected

omissions, most aect just one word: ve involve και, ve involve an article (η bis, ο, τον, του),

four involve a pronoun (αυτω, μου bis, τουτο), and two involve a preposition (ϲυν, εκ). Also

corrected are the omission of the verb ειϲιν and the noun ετη.

e remaining seven omissions involve more than one word. Four of these appear to be

erroneous leaps forward. At Matt 26:49–50, the scribe of P37 leapt from the ειπεν of 26:49 to

the ειπεν of 26:50, thus omitting χαιρε, ραββι, και κατεφιληϲεν αυτον. ο δε ειπεν. e inter-

linear correction δε ο (assuming this is an accurate transcription), fails to make sense of

the text, although it is possible that the rest of the omitted text was supplied in the now-lost

margin.

55

At John 1:38a in P5, the scribe omitted οι δε by leaping forward: [ζητει]τε οι δε. e

same scribe made another leap at John 16:23–24, from εν τω ονοματι μου in verse 23 to the same

words in verse 24, thereby omitting εν τω ονοματι μου εωϲ αρτι ουκ ητηϲατε ουδεν. e errone-

52

INTF expresses some caution about this reading, adding “vid,” but Royse cites it without hesita-

tion: James R. Royse, “e Early Text of Paul (and Hebrews),” in Hill and Kruger, Early Text of the

New Testament, 175–203 (197).

53

e original scribe of 0169 marked the omission and correction with an anchora symbol (↑).

54

Reconstruction taken from Peter Malik, “P.Oxy. VIII 1080: A Fresh Edition and Textual Notes on

a Miniature Codex of the Apocalypse,” APF 63 (2017): 310–20.

55

NA28 lists the error in P37 at Matt 26:49–50 as two separate variation units (the lengthy omission

and an addition of αυτω), but this is probably misleading. e explanation given above removes

the need to posit the addition of αυτω. For discussion, see Kyoung Shik Min, Die Früheste Über-

lieferung des Matthäusevangeliums (bis zum 3./4. Jh.): Edition und Untersuchung, ANTF 34 (Berlin:

de Gruyter, 2005), 89 n. 3.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 31

ously omitted text was supplied in the lower margin, possibly by a second hand.

56

At Rev 3:20,

the scribe of 0169 erroneously leapt over κρ̣ο̣υω ε[α]ν̣ … [θυραν και] due to homoioteleuton

and supplied the text in the lower margin in the same hand.

e omission at Matt 13:35 in 0242 does not have any obvious explanation and appears to

be a simple lapse. In the case of Rev 4:3 in 0169, the corrector has mistakenly added επι τον

θρ̣[ονον] aer ο καθημενοϲ, harmonizing to the immediate context and creating a singular read-

ing in the process.

e nal two corrected omissions occur in 0270 at the same point in 1 Cor 15:10. e scribe

originally wrote η χαριϲ ϲυν εμοι, an otherwise unattested reading. A corrector later added του

, making η χαριϲ του ϲυν εμοι, which is an attested but minority reading. A second cor-

rector then added another article, resulting in η χαριϲ του η ϲυν εμοι, which is the majority

reading. In making the addition of η, the latter scribe partially eaced του .

57

Two more examples are possible but uncertain.

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 10:33 om.? 0171 037* 157

[οϲτιϲ δ αν] α̣ρν[ηϲηται με ενπροϲ]| θεν

των̣ [] αρ[νηϲομαι καγω αυτον]|

ενπροϲθεν το[υ μου του εν ]

0171

2c

rell

Rev 11:9a

58

om. P115* rell

κ̣α̣[ι]? P115

2c

(post εθνων) solus?

In the upper margin of 0171, the text of Matt 10:33 is written in a smaller, second hand.

Because the folio is lacunose where the text should have been written originally, it can only

be presumed that the original scribe omitted that verse (due to homoioteleuton). e second

possible correction, Rev 11:9 in P115, is uncertain due to partial illegibility.

6. Additions

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Acts 10:29

ουν P50* solus

om. P50

c

rell

(τω 08 1884)

1 Pet 2:23

τον τ̣[οπον] P81* solus τ̣[οπον] P81

c

l1575

(om. rell)

Rev 2:27

αυτου[ϲ] P115* solus

om. P115

c

rell

Rev 3:10

[τ]ο̣υϲ P115* solus

om. P115

c

rell

Rev 13:18

η P115* solus

om. P115

c

rell

56

As suggested in the ed. princ.: “is mistake has been corrected at the foot of the page, where l. 35

has been rewritten in a smaller and probably dierent hand with the missing words incorporat-

e d .” Pace Blumell and Wayment, Christian Oxyrhynchus, 44, who attribute it to the rst hand. e

poor state of the manuscript makes identication of the hand dicult.

57

Cf. the suggestion in the ed. princ.

58

e manuscript is dicult to read at this point, but if the transcription of κ̣α̣[ι] is accurate, it is

a correction that creates a nonsense reading. One possible explanation for it could be the close

proximity of τα [πτωματα] (INTF) or τα [πτωμα] (ISBTF) in l. 22 and [τα πτωματα] in l. 23, the

second of which is (correctly) preceded immediately by κα[ι]. e corrector might have confused

the two and mistakenly added και to the rst.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts32

ere are ve corrected additions in our manuscripts. ree of these are obvious cases of erro-

neous dittography: ουν τινι ουν (Acts 10:29), τ̣ον τον (1 Pet 2:23), and [τ]ο̣υϲ τ̣[ουϲ] (Rev 3:10).

Particularly interesting is the insertion of αυτου[ϲ] at the end of Rev 2:27. According to

NA28, the wider context runs thus: καὶ ποιμανεῖ αὐτοὺϲ ἐν ῥάβδῳ ϲιδηρ ὡϲ τὰ ϲκεύη τὰ

κεραμικὰ ϲυντρίβεται (2:27), which is clearly a paraphrase of Ps 2:9 (LXX): ποιμανεῖϲ αὐτοὺϲ

ἐν ῥάβδῳ ϲιδηρ, ὡϲ ϲκεῦοϲ κεραμέωϲ ϲυντρίψειϲ αὐτούϲ. Herman Hoskier’s collations show

that no witness to John’s Apocalypse other than P115* has αυτουϲ aer ϲυντριβεται.

59

While it is

possible that the copyist erroneously repeated αυτουϲ from the rst clause, it seems equally as

likely that the addition reects harmonization to Ps 2 (LXX).

60

At Rev 13:18 in P115, it is clear that an eta stands before the numeral , and it is further clear

that a dot was written above it. However, it is not entirely certain that the dot is a cancellation

dot (what precedes it is lacunose), and it is unclear what this letter could have meant in the rst

place.

61

Still, the most plausible explanation seems to be that the eta is a canceled error (or the

end of one). If so, this error was corrected prior to the writing of .

ere is another possible instance of a corrected addition:

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

John 1:38b

αυ|[τω] P5* rell

om.? P5

c

178 251 1424

e IGNTP transcription records deletion dots above the rst two letters of αυ|[τω] in con-

junction with the corrected omission οι δε in John 1:38a (see above). It is unclear why αυ|[τω]

would be canceled, since this would put P5 out of step with the vast majority of manuscripts.

e poor state of the papyrus makes it dicult to be certain about the reading here.

7. Substitutions

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 10:25c

62

[επεκα?]|λεϲεν P110* solus [επεκα]|λεϲαν P110

c

? 01

c

03 04 017 032 037

f

13

565 579 pm

(εκαλεϲαν 038 0171 f

1

700 1424 pm |

απεκαλεϲαν 030 034 157* 267 270 291

473 713 998 1200 1170 | εκαλεϲαντω 019 |

επεκαλεϲαντο 01* 022 042 043 4 16 59 273

1010 1293 1555 1604 | καλουϲιν 05)

Matt 26:24

63

εγενηθη P37* 02 038 28 579 700* εγεννηθη P37

2c

rell

Mark 2:22

64

[βα]λ̣ ει ̣ P88* 0211 117* 273 713 [βα]̣ ει ̣ P88

c

rell

(βαλι 038 | βαη 732* 829)

59

Herman C. Hoskier, Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 2 vols. (London: Quaritch, 1929),

2:88–89.

60

Parker suggests that either the exemplar contained annotations on another text or that the scribe

consulted another copy or copies (“New Oxyrhynchus Papyrus,” 163).

61

See Parker, “New Oxyrhynchus Papyrus,” 160 n. 7.

62

e ed. princ. notes that P110 could have read either επεκαλεϲαν or εκαλεϲαν here.

63

e second hand is suggested by Sanders in the ed. princ., but see Wasserman, “Early Text of

Matthew,” 91, who suggests rst hand.

64

ECM has a question mark here for the reading of P88*.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 33

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Acts 8:32c

αυτου P50* solus

65

αυτον P50

c

rell

(αυτο 321)

Rom 8:21

[ελευθερ?]ωθη [εκ?] P27* solus [ελευθερο]υται απ̣[ο] P27

2c

solus

(ελευθερωθηϲεται απο rell)

1 Cor 15:14

ημων 0270* 03 06* 049 0243 33 81

1241 1739 1881 l147 al

υμων 0270

c

rell

Eph 1:19

π̣λ̣ ουτο[ϲ] P92* solus υ̣π̣ερβα[ον] P92

c

rell

(υπερ 385 | υπερβαων 1877 | om. 010 012)

Phlm 19

αυτο[ν] P139* solus εαυτο[ν] P139

c

0150 256 263 365 1241 1933

2110

66

(ϲεαυτον rell)

Heb 9:14

67

[π]οϲ̣[ω] P17* rell [π]ο̣ [ω] P17

c

33 1751

Heb 11:4

αυτoυ P13* rell αυτω P13

c

solus

Rev 1:6

του ̣ P18* 2196 τω̣ ̣ P18

c

rell

Rev 3:19

ζ

̣

ηλε̣υε̣ 0169* rell

ζ

̣

ηλωϲον 0169

2c

01 025 2053 M

A

(ζηλου 314 617 664 743 1094 2016 2075

2077 2078 2436 | ζητηϲον 1957)

Rev 3:21b

ν̣ενεικηκ[α] 0169* solus ενικηϲ[α] 0169

2c

rell

Rev 3:21c

κ̣εκαθι̣κα 0169* solus εκαθι̣ϲα 016

2c

rell

(εκαθειϲα 02 | εκαθηϲα 046 69 181 922 935

1894 1918 2026 2033 2036 2043 2047 2050

2052 2065* 2082 2329 2351)

Rev 9:20

68

[προϲκυνη]ϲ̣ουϲι̣[ν] P115* P47 01

02 04 104* 452 459 467* 922 1828

2019 2021 2082 2084

[προϲκυνη]ϲ̣ωϲι̣[ν] P115

c

rell

(προϲκυνιϲωϲι 1864)

Several of these substitutions might simply be orthographical slips (Matt 10:25c; 26:24; Mark

2:22; 1 Cor 15:14; Rev 9:20) or visual confusions (Acts 8:32c), but they have in any case created

alternative readings. One error was caused by a leap back: in P92* at Eph 1:19, aer writing

τι το, the scribe accidentally leapt backward to τιϲ ο (in 1:18) and wrote πλουτοϲ instead of

65

Von Soden lists δ602 (= GA 522) in support of αὐτοῦ, apparently in error. Manuscript images

show that, although the script sometimes makes it dicult to discern the dierence between nu

and upsilon, the word is accented as αὐτὸν.

66

Von Soden lists α174 (= GA 255) as support for εαυτον in Phlm 19, but we are unable to verify this

reading.

67

We follow the INTF transcription and the ed. princ., although the editor notes some uncertainty:

“But the decipherment is doubtful, the rst supposed λ being of a curiously rounded shape.” Pace

Klaus Wachtel and Klaus Witte, eds., Die Paulinischen Briefe: Gal–Hebr, vol. 2.2 of Das Neue Tess-

tament auf Papyrus (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1994), xliii, who observe the interlinear text but express

doubt that it was intended as a correction.

68

e presence of the movable nu at the end of προϲκυνηϲουϲιν (Rev 9:20 in P115) is uncertain, so

Hoskier’s textual evidence has been simplied to focus on the relevant variation between -ου-

and -ω-.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts34

υπερβαον but caught the error and corrected it.

69

And in one case the scribe appears to have

attempted to improve the sense of the text (P13 at Heb 11:4).

70

Four substitutions involve the change of verb tense. According to the most recent analysis

of P27, the original reading at Rom 8:21 was either ελευθερωθη εκ or ηλευθερωθη εκ, either of

which would be a singular reading that substitutes an aorist passive in place of the majority

reading of the future passive (ἐλευθερωθήϲεται).

71

e correction, however, created another

singular reading, a present middle/passive form, which certainly changes the sense of the text

here. Somewhat similar is the correction at Rev 3:19 in 0169. e original scribe wrote ζηλευε

(present imperative) in line with the majority reading, but a secondhand corrector altered it to

the relatively rarer aorist imperative ζηλωϲον. Twice the corrector rectied unique readings of

the original scribe, who had wrongly substituted perfect indicatives for aorist indicatives (Rev

3:21b, c).

e remaining three corrected substitutions are dicult to explain. One of these might

reect harmonization. In P18 at Rev 1:6, the scribe initially wrote ϊερειϲ του but quickly

corrected it to ϊερειϲ τω̣ ̣. e phrase ἱερεῖϲ τ θε with the dative occurs only here in all of

the LXX and New Testament (and ἱερεύϲ τ θε never), but the same construction with the

genitive (ἱερεῖϲ τοῦ θεοῦ or ἱερεύϲ τοῦ θεοῦ) appears occasionally.

72

In any case, since the omega

of ̣ stands immediately aer the canceled upsilon and before the next word, it is clear the

scribe made the correction in scribendo.

e substitution in P139 at Phlm 19 could simply be a scribal slip (the omission of ϲε-), but

both the original reading and its correction are understandable alternatives. It is unclear what

would have caused the error.

In P17 at Heb 9:14, the scribe originally wrote the majority reading ποϲω μαον but appears

to have corrected it to ποω μαον. Given the scant support for this reading, it seems unlikely

to have been inuenced by another exemplar. In addition, since the latter reading is only

slightly more common in the New Testament than the former, it was probably not caused by

harmonization to familiar wording.

73

One more corrected substitution is possible but uncertain due to the poor state of the papy-

rus. Although not noted in the ed. princ., the INTF transcription notes the following as a

possible correction in P53:

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 26:39b

α̣υ̣του P53* rell ε̣α̣υ̣του? P53

c

solus

69

See Royse, “Early Text of Paul,” 197.

70

See the discussion in Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament

(London: United Bible Societies, 1971), 671–72 (rst edition, not in the second edition), though

he suggests it is a transcriptional error.

71

Samuli Siikavirta, “P27 (Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1355): A Fresh Analysis,” TC 18 (2013): 1–10 (7). See

also Royse, “Early Text of Paul,” 191.

72

Heb 7:1; Rev 20:6; Gen 14:18; 1 Sam 14:3.

73

E.g., ποω μαον: Matt 6:30; Mark 10:48; Luke 18:39; Rom 5:10, 15, 17; 1 Cor 12:22; 2 Cor 3:9, 11;

Phil 2:12. ποϲω μαον: Matt 7:11; 10:25; Luke 11:13; 12:24, 28; Rom 11:12, 24.

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 35

8. Transposition

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Acts 10:31c

του̣ ̣ ενωπ̣ι̣ον P50* solus ενωπ̣ι̣ον του P50

c

rell

Acts 23:27b

υπο των ιο̣υ̣δαιων ϲυνλημφθεντα

P48* solus

ϲυνλημφθεντα υπο των ιουδαιων P48

c

08

(ϲυηφθεντα υπο των ιουδαιων pm)

Two corrections involve erroneously transposed wording. One might be tempted to classify

these errors as dittographies, since they result in the doubling of words. However, it is more

likely in both cases that the scribes mistakenly transposed the wording of their exemplar. In

the case of Acts 10:31c in P50, the scribe should have written εμνηϲθηϲαν ενωπιον του , but the

text appears as: εμνηϲ|θηϲαν του ενωπιον | του . Strictly speaking, this could be classied as

an addition of του . However, the more likely cause of error was a leap over ενωπιον, which

was immediately caught and xed by deleting the preempted word and writing the text in the

correct sequence. e same explanation makes the most sense of the error at Acts 23:27b in

P48.

74

e scribe should have written τον ανδρα τουτον ϲυνλημφθεντα υπο των ιουδαιων, but

the text appears as: τον ανδρα τουτον υπο των ιουδαιων ϲυνλημφθεντα υπο των ιουδαιων. e

scribe most likely leapt over ϲυνλημφθεντα but immediately caught the error, deleted the initial

υπο των ιουδαιων, and wrote the text in the correct sequence. As such, both of these constitute

corrections made in scribendo.

9. Uncertain

9.1. Uncertain Category

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Matt 10:25d

[βεελζε?]βουλ 0171* [βεελζε?]ββουλ 0171

c

(βεελζεβουλ rell | βεεζβουλ 349 | βεεζεβουλ 01 03

| βελζεβουλ 05 019 033 16 566* 1093*)

Matt 10:33

75

α̣ρ̣νη̣ ϲ̣[ομε?] P19* α̣ρ̣νη̣ ϲ̣[ομ]α̣ι̣ P19

c

rell

(απαρνηϲομαι f

1

| αρνηϲομε 01 038 | αρνηϲωμαι 045

1071 | αρνηϲωμε 017 019 2* 28

c

| αρνιϲομαι 579)

Matt 26:46

76

αγ

̣

[?]μεν P37* αγ

̣

ωμεν P37

c

rell

(αγομεν 045 2372*)

Mark 2:12

ε̣ξ

̣

? P88*

om. P88

c

rell

( 79)

Acts 10:31d

77

ειϲη[?]ουϲθ̣η̣ P50* ειϲηκουϲθ̣η̣ P50

c

rell

(εηϲηκουϲθη 2344 | εηϲηκουϲθηϲαν 1890)

74

Note, e.g., that Christopher Tuckett, “e Early Text of Acts,” in Hill and Kruger, Early Text of the

New Testament, 157–74 (168), classies the error in P48 as dittography.

75

Printed here is the INTF transcription, pace the editor: “ere is no room for αρνηϲομαι or -με,

and the scribe evidently made some error; possibly he wrote αρνηϲω.”

76

According to Min, Die Früheste, 89, “αγομεν P37*

vid

.”

77

Εd. princ.: “e kappa of εἰϲηκούϲθη is superimposed upon an indistinguishable letter.”

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts36

Reference Uncorrected Text Corrected Text

Acts 10:31e

78

[?] P50*

αι P50

c

rell

(om. 020 049 81 218 319* 326 636 1243 1751 1838

1852 2147 2344)

Acts 23:12

[?]εγοντ̣εϲ P48* λεγοντ̣εϲ P48

c

pm

(om. pm)

Heb 10:12

79

π̣ροϲε[?]εγ

̣

καϲ P13* π̣ροϲεν̣εγ

̣

καϲ P13

c

rell

In many cases, it is certain (or nearly so) that a scribal correction has been made, but for some

reason the error cannot be categorized with condence. For example, on several occasions

scribes corrected themselves by overwriting an erroneous letter that is now illegible, as in P13

(Heb 10:12), P37 (Matt 26:46), P48 (Acts 23:12), and P50 (Acts 10:31d, 31e), which may reect

either orthography, nonsense (strict or contextual), or substitution, if the original reading

could be discerned.

At Matt 10:33 in P19, half the word in question is lacunose due to manuscript damage, so the

exact nature of the correction cannot be determined. e same is true of 0171 at Matt 10:25d. At

Mark 2:12 in P88, the scribe wrote something prior to ωϲτε and then erased it, leaving a mostly

blank space with just traces of εξ. Assuming this is the correct transcription, it would suggest

that the scribe either leapt over ωϲτε and began writing the following word, εξιϲταϲθε̣, or leapt

back to εξηλθεν. Either way, this correction would classify as in scribendo.

9.2. Stray Letters, Marks, and Traces of Ink

In many cases scholars note stray letters or traces of ink that very well could be corrections but

lack sucient context or clarity for certainty. ere are too many of such instances to catalog

here, so we oer the following simply by way of illustration:

Manuscript Notes

P13

INTF notes a possible but now unreadable interlinear correction aer εχει at Heb

3:3 (f.47v l. 15).

P16 According to the ed. princ. at Phil 4:3 (v l. 23): “ere are some faint marks above

the ζ which might be interpreted as an over-written ν (ϲυνζυγε), but they are not

certainly ink.”

P21

According to the ed. princ. at Matt 12:32 (r l. 6): “Traces of ink above το[υτ]ω per-

haps indicate a correction.”

P38

According to Comfort and Barrett at Acts 18:28 (r l. 2), the omicron of ευτονωϲ was

written over “a letter that is unable to be deciphered.”

80

P69 According to omas Wayment, there are traces of a correction at Luke 22:41 (→

l. 2).

81

78

Εd. princ.: “αἱ may rst have been ω.” INTF, however, suggests η.

79

e ed. princ. transcribes this word as προϲενεν̣καϲ and comments, “e second ν if it be ν, in

προϲενενκαϲ was converted from ι or υ. e previous ν also seems to have been altered.” In contrast

to the rst statement, here we follow the INTF in transcribing as -εγ

̣

καϲ.

80

Comfort and Barrett, Complete Text (1st ed.), 135.

81

omas A. Wayment, “A New Transcription of P. Oxy. 2383 (P69),” NovT 50 (2008): 351–57 (354).

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 37

Manuscript Notes

P81 e editor notes the presence of an anchora symbol (↑) in the margin (at 1 Pet 3:7),

which oen signals the presence of a correction (cf. the omission in 0169 at Rev

3:20 above).

82

However, manuscript damage prevents certainty about the function

of the symbol here.

83

P86

INTF notes the interlinear letter μ aer κρυβηναι at Matt 5:14 (r l. 5).

P115

e ed. princ. notes possible a correction above τω at Rev 2:14 (pp. 3–4, l. 3) and

a possible deletion aer φωνην at 10:4 (pp. 13–14, l. 113–114). In addition to these,

note what appears to be a supralinear eta in 2:15 (pp. 3–4, l. 6); a supralinear pi aer

ημιϲυ at 11:9b (pp. 17–18, l. 164); and what appears to be a deletion stroke at 11:15 (pp.

17–18, l. 175).

P132 According to the ed. princ. at Eph 3:21 a visible ink stroke above the tau might be a

now-lost interlinear correction (↓ 4).

P133 According to the ed. princ. at 1 Tim 3:15 there are some ink strokes that might be

traces of interlinear corrections (↓ 9).

P138 According to the ed. princ. at Luke 13:27 there is some superscripted ink that might

be a correction (↓ 7).

P139

According to the ed. princ. at Phlm 20, there are possible deletion dots over ρ and

χ (↓ ll. 8–9).

057 According to the ed. princ. at Acts 3:10, the scribe initially wrote and then partially

erased an iota adscript in τω (col. 2, l. 3).

84

0169 According to the ed. princ. at Rev 4:1, portions of hair side ll. 18–19 have been cor-

rected and/or reinked.

85

Similarly, at 4:2 (l. 25) there are traces of a marginal correc-

tion that could be a και.

0220 Recent analysis of this fragment suggests that there is evidence of a scribal correc-

tion at Rom 5:3 (r. l. 12), but physical damage prevents certainty.

86

10. Corrections Made In Scribendo

Above we noted certain corrections that could be classied with some condence as in

scribendo, or made by the original scribe while in the process of copying. Here we repeat them

for ease of reference, recalling that in one case there is some uncertainty due to illegibility

(indicated by an asterisk).

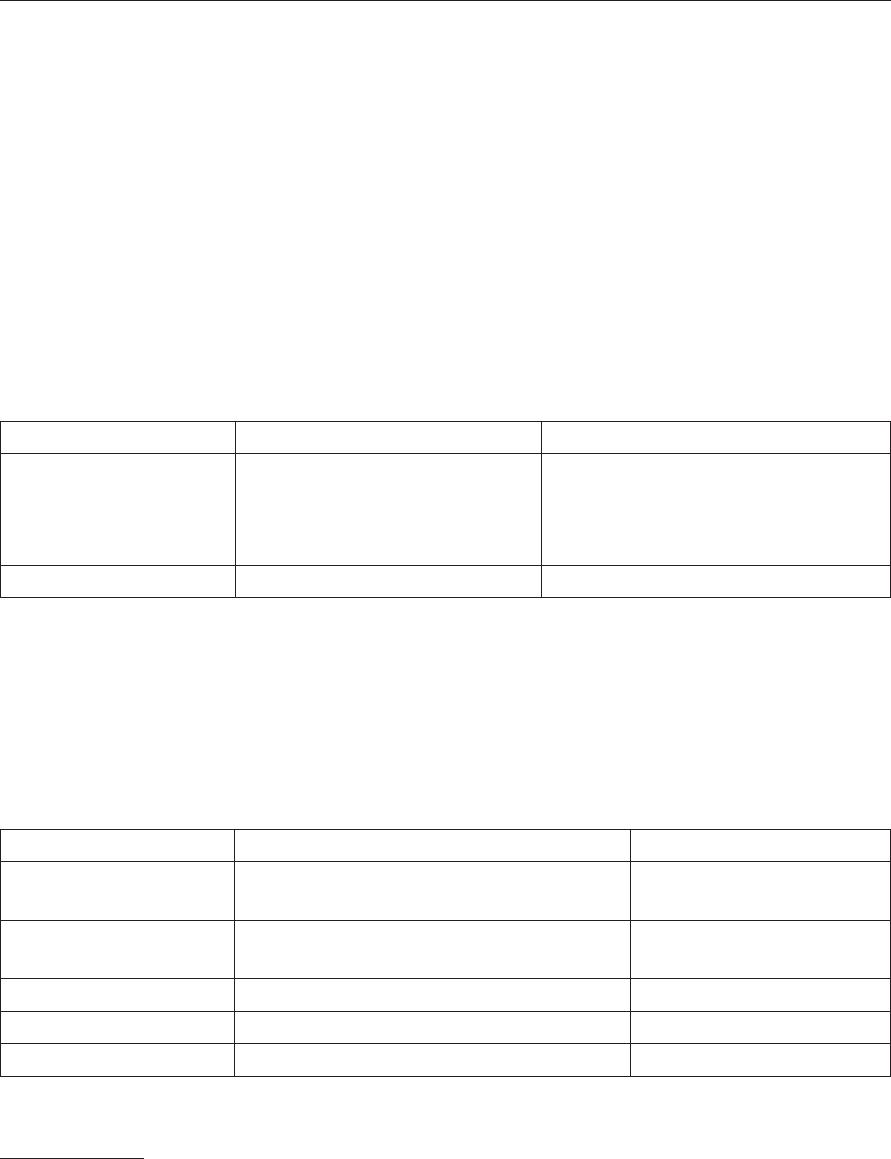

Manuscript Reference Type of correction

P4 Luke 3:29 orthography

P13 Heb 10:16 nonsense in context

P15 1 Cor 7:23a, 23b* orthography

P18 Rev 1:6 substitution

82

E. G. Turner, Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World, Bulletin Supplement 46 (London: Institute

of Classical Studies, 1987), 15–16; Alan Mugridge, Copying Early Christian Texts: A Study of Scribal

Practice, WUNT 2/362 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016), 102.

83

ECM lists several possible textual variants in 1 Pet 3:7.

84

More likely, the mark is a line ller (cf. col. 2 l. 7).

85

But see the cautionary remarks in Malik, “P.Oxy. VIII 1080,” 317–18.

86

Daniel Stevens, “e Wyman Fragment: A New Edition and Analysis with Radiocarbon Dating,”

NTS 68 (2022), 431–44 (esp. 439).

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts38

Manuscript Reference Type of correction

P48 Acts 23:27b transposition

P50 Acts 8:32a orthography

Acts 10:28b, 30b nonsense in context

Acts 10:30a, 31a strictly nonsense

Acts 10:31c transposition

P88 Mark 2:12 uncertain category

P106 John 1:33 strictly nonsense

P115 Rev 13:18 addition

A signicant observation to be made here is the variety of categories that were subject to

in scribendo corrections by the rst hand. Every category of error is represented here, with the

exception of omission (unless the uncategorized correction in P88 at Mark 2:12 qualies as

such). Moreover, the relative proportion of categories of in scribendo corrections corresponds

well to the overall tally of all corrections (see §12), with the exception of omission. As we

have seen, the category of corrected omissions is prominent among corrections as a whole,

constituting no less than 20 percent, but it is virtually unrepresented among those that can

be identied as in scribendo. is fact is unexpected. It could suggest that scribes were less

likely to catch omissions while in the process of copying compared to other categories of error.

However, the perhaps more likely explanation is that in scribendo corrections of omissions are

simply dicult for modern-day editors to identify. Because omissions are normally corrected

by scribes via interlinear insertion of the omitted text (rather than in-line correction), it is

generally more dicult to determine when these were made. us, many of the corrected

omissions identied here may well have been made by the rst hand while in the process of

copying, but they cannot be identied with condence due to their interlinear placement. In

any case, it is signicant that scribes could be attentive to virtually every category of error

while in the process of copying.

11. Later Correctors

Determining the identity of correctors is challenging even in well-preserved and clearly pho-

tographed manuscripts. It is all the more dicult in fragmentary and poorly photographed

ones. We have, therefore, simply noted the suggestions of manuscript editors who perceive

evidence of a later hand and summarize these here, recalling that in certain cases there is some

uncertainty due to illegibility (indicated by an asterisk):

Manuscript Reference Type of correction

P5 John 16:23–24 omission

P27 Rom 8:21 substitution

P37 Matt 26:24 substitution

Matt 26:28 orthography

Matt 26:29 omission

P53 Matt 26:39a omission

P70 Matt 24:14 omission

P77 Matt 23:37b omission

P86 Matt 5:13 omission

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts 39

Manuscript Reference Type of correction

P88 Mark 2:10 nonsense in context

P103 Matt 13:56 omission

P115 Rev 8:7; 14:20* orthography

Rev 11:9a* omission

0169 Rev 3:19, 21b, 21c substitution

Rev 3:21a; 4:3 omission

0171 Matt 10:33* omission

Luke 22:45 strictly nonsense

0220 Rom 5:3 orthography

0270 1 Cor 15:10a, 10b omission

Particularly striking here is the high percentage of secondhand corrections in the category

of omissions. While there are a total of twenty-ve corrected omissions, no fewer than eleven

(possibly thirteen) of these are corrections by a second hand. In contrast, the category of

orthography has a comparable total of twenty-one corrections, but only three (possibly four)

of these are by a later hand. is dierence in frequency could have several explanations. It

may be that we are seeing an indication of what was happening in the various stages of quality

control and that secondhand correctors were especially attuned to the possibility of omissions.

However, it is also possible (and probably more likely) that corrected omissions are simply

easier for modern editors to identify as secondhand since the supplied text oers more hand-

writing for analysis and comparison. In comparison, for example, by their nature deletion dots

or strokes over added text usually do not provide an adequate writing sample to compare with

the rst hand. us, the high percentage of secondhand corrections of omissions is probably

skewed by the fact that they are more easily identied as such compared to other categories of

correction.

In only a few cases did editors identify a thirdhand corrector. P88 shows evidence of two

distinct correctors aer the original scribe on at least one occasion (strictly nonsense in Mark

2:19) and possibly again (nonsense-in-context reading in 2:25). Likewise, 0270 appears to have

a two-step correction process aer the original scribe at an omission in 1 Cor 15:10.

12. Summary and Conclusion

By way of summary and conclusion, some observations are in order. As noted in the beginning

of the study, out of the 114 manuscripts included in this sample, seventy lack clear indication

of a scribal correction, while thirty-seven contain at least one correction. Seven more manu-

scripts possibly qualify. is means that roughly one third of the manuscripts examined here

have at least one visible correction. Of course, the fragmentary nature of the artifacts means

the true number of manuscripts with scribal corrections is probably much higher. We are

glimpsing only bits and pieces of the material evidence.

e majority of the corrections appear to have been made by the copyists themselves, and

some (although few) of these can further be classied as in scribendo. e in scribendo cor-

rections reect all categories of errors with the exception of omissions, which is most likely

attributable to the dicultly of discerning precisely when an interlinear correction was made.

At least fourteen manuscripts seem to have had a secondhand corrector aer the original

scribe (possibly a diorthōtēs), and these frequently rectify erroneous omissions. e high per-

centage of corrected omissions attributable to a second hand probably reects the fact that

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts40

supplied text lends itself to identication as secondhand more so than deleted text. Only two

manuscripts show evidence of a thirdhand corrector.

We can also make summative observations about the categories of corrections made

(excluding those listed as only possible), although, as we saw above, some corrections could be

categorized in dierent ways:

Type of Correction Total number

Orthography 21

Nonsense 26

(Strictly nonsense 13)

(Nonsense in context 13)

Omission 25

Addition 5

Substitution 15

Transposition 2

Uncertain 8

Total 102

Even if a handful of the corrections were to be categorized dierently, we are nevertheless

able to make some instructive observations of these results. It is not surprising that the two

largest categories of corrected errors are nonsense readings and omissions, which together

constitute half of all the corrections identied. e high frequency of these two categories of

corrections accords well with the ndings of other recent studies, although a full comparison

with these is beyond our scope here.

87

It appears likely that the high frequency of corrections

to nonsense in this and other studies stems from the fact that, given their nature, nonsense

readings would be among the easiest errors for a scribe or corrector to identify.

With respect to omissions, it is surely signicant that we nd ve times the number of cor-

rected omissions than we do additions. e relatively high frequency of corrected omissions

probably reects the now widely recognized tendency among early scribes to omit rather than

to add.

88

at is, the most likely reason why we nd more corrected omissions than additions

is because scribes were more frequently omitting text than adding text in the rst place.

e high percentage of orthographical corrections is arguably the most surprising result of

this study and merits further attention.

89

Unlike nonsense errors and omissions, we might pre-

87

Cf. Royse, Scribal Habits, esp. 227–28, 436–42, 563–65, 634–37; Royse, “Corrections in the Freer,”

185–226; Jongkind, Scribal Habits, esp. 159; Malik, P.Beatty III, 97.

88

E. C. Colwell, “Scribal Habits in Early Papyri: A Study in the Corruption of the Text,” in e Bible in

Modern Scholarship: Papers Read at the 100th Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, December

28–30, 1964, ed. J. Philip Hyatt (Nashville: Abingdon, 1965), 370–89; republished in E. C. Colwell,

Studies in Methodology in Textual Criticism of the New Testament, NTTS 9 (Leiden: Brill, 1969),

106–24; Peter M. Head, “Observations on Early Papyri of the Synoptic Gospels, Especially on the

‘Scriba l Habits,’ ” Bib 71 (1990): 240–47; Peter M. Head, “e Habits of New Testament Copyists:

Singular Readings in the Early Fragmentary Papyri of John,” Bib 85 (2004): 399–408; Jongkind,

Scribal Habits, 246; Juan Hernández Jr., Scribal Habits and eological Inuences in the Apocalypse:

e Singular Readings of Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, and Ephraemi, WUNT 2/218 (Tübingen: Mohr

Siebeck, 2006), 87–88; Royse, Scribal Habits, 705–36; Malik, “Earliest Corrections in Codex Sinait-

icus: Further Evidence from the Apocalypse,” 8; Wilson, “Scribal Habits,” 97–105.

89

In fact, as noted above, many corrections classied as nonsense in context (Mark 2:10; Heb 10:19;

1 Pet 3:10) and substitutions (Matt 10:25c; 26:24; Mark 2:22; Rev 9:20) might simply have been

Scribal Corrections in Early Greek New Testament Manuscripts

© Copyright TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism, 2023

41

sume that orthographical errors by nature would be less easily identied by the original scribe

or a later corrector. Such would seem to be the case in some recent studies of scribal correc-

tions, specically of the rsthand corrections in Codex Sinaiticus, which report proportionally

fewer orthographical corrections.

90