S S

Space War in Ukraine

Robin Dickey

Michael P. Gleason

A W S

Jake Suss

US Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve

Gary L. Davenport

Offensive Dominance in Space

Brian R. Goodman

Funding National Defense

Hardwired for Hardware

T S

C N

E W

M I

Douglas E. Lumpkin

Philip N. Stewart

Joel D. Kornegay

L T US A

David J. Kritz

Shane A. Smith

Narratives in Conflict

D A

Robert S. Hinck

Sean Cullen

Vol. 3 No. 1 S 2024

A Journal of

Strategic Airpower & Spacepower

Chief of Staff, US Air Force

Gen David W. Allvin, USAF

Chief of Space Operations, US Space Force

Gen B. Chance Saltzman, USSF

Commander, Air Education and Training Command

Lt Gen Brian S. Robinson, USAF

Commander and President, Air University

Lt Gen Andrea D. Tullos

Chief Academic Officer, Air University

Dr. Mark J. Conversino

Director, Air University Press

Dr. Paul Hoffman

Editor in Chief

Dr. Laura M. urston Goodroe

Mark J. Conversino, PhD

James W. Forsyth Jr., PhD

Kelly A. Grieco, PhD

John Andreas Olsen, PhD

Nicholas M. Sambaluk, PhD

Evelyn D. Watkins-Bean, PhD

John M. Curatola, PhD

Christina J.M. Goulter, PhD

Michael R. Kraig, PhD

David D. Palkki, PhD

Heather P. Venable, PhD

Wendy Whitman Cobb, PhD

https://www.af.mil/ https://www.spaceforce.mil/ https://www.aetc.af.mil/ https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/

Æther

A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower

Advisory Editorial Board

Senior Editor Print Specialists Illustrator Web Specialist Book Review Editor

Dr. Lynn Chun Ink Cheryl Ferrell

Diana Faber

Catherine Smith Gail White Col Cory Hollon, USAF, PhD

Æther

A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower

SPRING 2024 VOL. 3, NO. 1

3 Letter from the Editor

Funding National Defense

5 Hardwired for Hardware

Congressional Adjustments to the Administration’s Defense

Budget Requests, 2016 to 2023

Travis Sharp

Casey Nicastro

Spacepower and Strategy

20 Space and War in Ukraine

Beyond the Satellites

Robin Dickey

Michael P. Gleason

36 Asymmetric Warfare in Space

Five Proposals from Chinese Strategic Thought

Jake Suss

50 US Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve

Integrating Commercial Capabilities for a Resilient and Flexible

Space Architecture

Gary L. Davenport

66 Offensive Dominance in Space

Brian R. Goodman

Narratives in Conflict

81 Decoding the Adversary

Strategic Empathy in an Era of Great Power Competition

Robert S. Hinck

Sean Cullen

Ethics and Warfare

95 Moral Injury

Wounds of an Ethical Warrior

Douglas E. Lumpkin

Philip N. Stewart

Joel D. Kornegay

111 Lethal Targeting through US Airpower

A Consequentialism Perspective

David J. Kritz

Shane A. Smith

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 3

FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Reader,

In March, the administration released the Department of Defense’s scal year (FY)

2025 budget proposal, which reects the short- term belt- tightening implemented by

the FY 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act. e implications of this, coupled with the ten-

dency for Congress to default to appropriation by continuing resolution, portends an-

other year of overall programmatic development and execution uncertainty for the

Department. Ongoing global geopolitical unrest, compounded most recently by active

wars in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip and aided and abetted by nonstate actors, is occur-

ring simultaneously with the advent of what looks to be the most contentious US pres-

idential campaign in recent history.

In sum, there is no shortage of urgent national and international security topics

relevant to the Department of the Air Force worth exploring. Accordingly, our spring

issue of Æther: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower considers subjects rang-

ing from defense spending and space strategy to strategic narratives and ethics in war.

In Funding National Defense, Travis Sharp and Casey Nicastro analyze congressional

changes to budget requests from FY 2016 through FY 2023 and nd the legislative

branch has preferenced programmatic spending over personnel and operation and

maintenance expenditures, requiring DoD leaders to convey priorities clearly and

Congress to sustain critical levels of nonhardware defense spending.

Our Spacepower and Strategy forum leads with an article calling attention to

Ukraine’s novel use of space. Robin Dickey and Michael Gleason discuss how

Ukraine, a nonspacefaring nation, has made far better use of the domain than its

spacefaring adversary, Russia—particularly in the areas of ground infrastructure, so-

ware, and information- sharing practices. ese ndings yield signicant policy,

strategy, and doctrine lessons for the US armed forces. In the second article in the fo-

rum, Jake Suss oers ve proposals for space strategy based on historic Chinese strate-

gic thought. ese proposals center on exploiting asymmetric advantages that will

limit adversaries’ use of the domain and help the United States win conicts in and

through space.

e third article considers resiliency in space. Gary Davenport argues the newly

created Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve—modeled on the Civil Reserve Air

4 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

From the Editor

Fleet (CRAF)—should build on lessons learned from CRAF structure and implemen-

tation in order to ensure commercial interest in the program and overall success when

implemented. Lastly, Brian Goodman analyzes the US Space Force’s notion of com-

petitive endurance through international relations theory, proposing a new theory of

oense dominance in space and oering recommendations to mitigate the possibility

of conict in and through space.

Our third forum, Narratives in Conict, features an in- depth analysis of the notion

of strategic empathy. Robert Hinck and Sean Cullen explain the function strategic

narratives serve in the development and practice of strategic empathy and the role

such empathy plays in military planning and strategy.

In the rst article of our nal forum, Ethics and Warfare, Douglas Lumpkin, Philip

Stewart, and Joel Kornegay examine the occurrence of moral injury in US service

members. ey nd that while it can result in highly negative outcomes, it can build

readiness and resilience in military teams and organizations if leaders approach it cor-

rectly. e forum and our issue conclude with a discussion on lethal targeting/targeted

killing, viewed through the lens of the ethics theory of consequentialism. David Kritz

and Shane Smith propose a four- element, ethics- based model that military planners

can employ in situations involving the potential for lethal targeting/targeted killing.

ank you for your continued support of the journal. As always, we encourage

thoughtful, well- reasoned responses to our articles, with the potential for publishing

in a future issue. Æ

~e Editor

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 5

Funding National Defense

HARDWIRED FOR

HARDWARE

Congressional Adjustments to

the Administration’s Defense

Budget Requests, 2016 to 2023

Travis sharp

Casey NiCasTro

As a result of the 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act, defense budget growth will be limited for

scal year (FY) 2024 and FY 2025. An analysis of congressional adjustments to defense

budget requests from FY 2016 to FY 2023 reveals a Congress that favors programmatic

expenditures over personnel and operation and maintenance. In a time of scal austerity in

the near term, DoD priorities must be clearly and concisely conveyed to Congress, and

Congress must balance its predilection for hardware with the need to appropriately fund

the nonhardware programs and components of the Department.

A

er increasing the DoD budget in real terms during seven of the past eight

scal years (2016–23), Congress has pivoted toward suppressing spending by

passing the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

1

Approved in June 2023 as part of the

debt ceiling deal, the law limits defense budget growth for the next two years while

threatening automatic across- the- board cuts, known as sequestration, of approxi-

mately $40 billion below planned spending levels if Congress takes too long to pass

full- year appropriations.

2

ese provisions eectively hold the defense budget hostage

to incentivize Congress to complete its appropriations work on time.

e law’s ultimate eects on spending will depend on future congressional actions,

particularly how Capitol Hill handles regular and supplemental budget bills in 2024

and 2025. Despite these uncertainties, the shi from steady spending growth to sud-

den budgetary restraint indicates a mercurial Congress struggling to balance compet-

ing priorities and factions.

e Hill’s uneven approach to the defense budget’s size, with years of bipartisan

support for hey increases suddenly giving way to an intensive focus on spending

Lieutenant Commander Travis Sharp, USNR, PhD, is a senior fellow and director of defense budget studies at the

Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments in Washington, DC.

Casey Nicastro is an analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments in Washington, DC, and holds

a master in international relations from Johns Hopkins University’s Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced Interna-

tional Studies.

1. Travis Sharp, Inconsistent Congress: Analysis of the 2024 Defense Budget Request (Washington, DC:

Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments [CSBA], October 2023), 5, https://csbaonline.org/.

2. Sharp, 7.

6 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

limits, also characterizes its treatment of specic expenditures. Based on an analysis of

congressional adjustments to the administration’s defense budget requests from 2016

to 2023, this article nds that Congress has exhibited a programmatic orientation to-

ward defense spending characterized by adding funds for procurement and, to a much

lesser extent, research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E).

At the same time, Congress has subtracted funds for military personnel, including

service member pay and allowances, and operation and maintenance (O&M), includ-

ing ying hours, ship operations, training, and maintenance. In short, Congress has

retained its long- running xation on acquiring “hardware,” particularly favored weap-

ons systems such as missile defense, ships, and aircra. Of note, this article uses adjust-

ments as a generic term referring to Congress’ combined adding and subtracting of

funds to DoD budget requests, not as a technical term denoting the various processes

for realigning or reprogramming appropriated funds.

3

Congress’ preference for hardware is not exactly surprising. Lawmakers possess

compelling reasons to address defense spending programmatically.

4

As Charles Hitch,

creator of the Defense Department’s Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System,

observed in the 1960s, “ese [weapons systems] choices have become . . . the key

decisions around which much else of the defense program revolves.”

5

Other studies

have determined Congress’ obsession with big- ticket weapons programs remains alive

and well.

6

Still, the article’s reconrmation of this enduring pattern should alert de-

fense strategists as budgets atten during the Fiscal Responsibility Act’s two- year

timespan—and potentially remain at aerward due to continued congressional ad-

vocacy for spending limits, a political dynamic that dominated 2023.

e United States is currently navigating intense military competitions against

China and Russia while managing deadly conicts in Ukraine and the Middle East.

is extraordinarily demanding security environment, which blends long- term and

immediate challenges, necessitates varied investments across the Joint force. As Gen-

eral Mark Milley, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Sta, remarked in 2023, “We

must not allow ourselves to create the false trap that we can either modernize [for to-

morrow] or focus only on today—we must do both.”

7

3. Philip J. Candreva, National Defense Budgeting and Financial Management: Policy and Practice

(Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2017), 318–26.

4. Samuel P. Huntington, e Common Defense: Strategic Programs in National Politics (New York:

Columbia University Press, 1961), 3–7.

5. Arnold Kanter, “Congress and the Defense Budget: 1960–1970,” American Political Science Review

66, no. 1 (March 1972): 135.

6. Seamus P. Daniels and Todd Harrison, “Assessing the Role of Congress in Defense Acquisition Pro-

gram Instability,” paper prepared for the 18th Annual Acquisition Research Symposium, Naval Postgradu-

ate School, Monterey, CA, May 2021, https://dair.nps.edu/; and Report on Congressional Increases to the

Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 Defense Budget (Washington, DC: Department of Defense [DoD], August 4, 2023),

https://comptroller.defense.gov/.

7. Jim Garamone, “Milley Says Investments in Military Capabilities Are Paying O,” DoD, May 11,

2023, https://www.defense.gov/.

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 7

As budgets stagnate, if Congress does not moderate its hardware spending add- ons,

at least in select areas, then it risks shortchanging the “soware” underpinning US mili-

tary power, including people, readiness, education, and other key ingredients of combat

eectiveness oen funded through the military personnel and O&M budgets.

8

History shows the risk of underfunding these critical areas is real. Since the Cold

War’s end, military personnel and O&M cuts oen have exceeded procurement and

RDT&E cuts when defense spending stagnates, worsening readiness shortfalls during

those periods. Making hard trade- os between hardware and so- called soware

proved less necessary for Congress as it boosted defense budgets throughout the past

decade. Such trade- os will prove essential under the Fiscal Responsibility Act as well

as any prospective spending control agreement enacted in its wake. Congress will not

have to stop adding money for weapons systems, but it will likely have to lessen those

additions to ensure readiness receives the necessary funding.

If history is any guide, overcoming these diculties now and in the future will re-

quire both the Department of Defense and Congress to make improvements. e Pen-

tagon should nd new ways to persuade Congress to support essential investments,

particularly for nonhardware priorities. At the same time, military planners must de-

velop concepts to ght and win with what the Department already has. On the legisla-

tive side, Congress needs a stronger pipeline of defense policy entrepreneurs capable

of leading their colleagues to more sound decisions more of the time, specically by

harnessing their procedural power to elicit more impactful information from the Pen-

tagon. Without actions like these, Congress’ xation on hardware could inadvertently

produce a US military that is less broadly prepared to succeed in a dangerous world

where the margin of error has become perilously small.

9

Hypotheses and Data on Congressional Spending

Adjustments

Over the past 60 years, scholars have developed three competing hypotheses about

how Congress addresses the administration’s defense spending requests.

10

e negli-

gible hypothesis holds that Congress does not have a signicant impact on either the

overall level of defense spending or the allocation of spending across programs.

8. Michael C. Horowitz, e Diusion of Military Power: Causes and Consequences for International

Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 5; and Stephen Biddle, Military Power: Explaining

Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 203.

9. Robert M. Gates, “e Dysfunctional Superpower: Can a Divided America Deter China and Rus-

sia?,” Foreign Aairs 102, no. 6 (November/December 2023).

10. Raymond H. Dawson, “Congressional Innovation and Intervention in Defense Policy: Legislative

Authorization of Weapons Systems,” American Political Science Review 56, no. 1 (March 1962): 43; Edward

J. Laurance, “e Congressional Role in Defense Policy Making: e Evolution of the Literature,” Armed

Forces and Society 6, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 436–38; Barry M. Blechman, e Politics of National Security:

Congress and U.S. Defense Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 23–29; and Jamie M. Morin,

“Squaring the Pentagon: e Politics of Post- Cold War Defense Retrenchment” (Ph.D. diss., Yale Univer-

sity, May 2003), 306–7.

8 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

Proponents of this view imagine a Congress that essentially tinkers at the margins and

functions as “a pushover for the Pentagon,” as Senator William Proxmire (D- Wisconsin)

once put it.

11

If the negligible hypothesis holds true, then congressional spending adjust-

ments should appear small and inconsequential, generally adhering to the administra-

tion’s plans.

e scal hypothesis posits that Congress concerns itself with the defense spending

topline and pays limited attention to the particulars. Advocates of this model envision

a Congress that modies DoD funding requests primarily to achieve government-

wide budgetary goals. If the scal hypothesis holds true, then congressional spending

adjustments should concentrate on the largest portions of the defense budget—the

O&M and military personnel accounts—and exhibit an across- the- board or balanced

character, in dollar or percentage terms, consistent with a general indierence toward

specic programs.

e programmatic hypothesis claims that, as one analyst describes it, “Congress

addresses the defense budget in policy terms and uses its power of the purse as a

tool to inuence the shape of defense programs.”

12

Lawmakers may demonstrate a

programmatic orientation for strategic reasons, as when they feel that specic mili-

tary activities underpin America’s place in the world. ey may also focus on pro-

grams for parochial reasons, as when their constituents depend on funding associ-

ated with certain activities. In practice, these strategic and parochial motivations

oen overlap and may conict, making them dicult to disentangle.

13

If the pro-

grammatic hypothesis proves true, then congressional spending adjustments should

exhibit discernible patterns across time and category whereby funds ow toward

favored activities and away from disfavored activities.

To assess these hypotheses, the authors collected data on congressional defense

spending adjustments from scal year (FY) 2016 to FY 2023. e dataset started with

2016 because that was the rst year of the upward dri in defense spending referenced

in the introduction and ended with 2023 because that was the last year data were

available. e dataset contains adjustments as reported in Congress’ annual enacted

basic DoD appropriations bill, meaning it excludes military construction, family

housing, nuclear weapons activities, and supplementals, or extra expenditures added

outside the Department’s annual base budget request. Since the dataset covers only

11. Kanter, “Congress,” 129.

12. Lawrence J. Korb, “Congressional Impact on Defense Spending, 1962–1973: e Programmatic

and Fiscal Hypotheses,” Naval War College Review 26, no. 3 (November–December 1973): 50.

13. James M. Lindsay, “Parochialism, Policy, and Constituency Constraints: Congressional Voting on

Strategic Weapons Systems,” American Journal of Political Science 34, no. 4 (November 1990); James M.

Lindsay, Congress and the Politics of U.S. Foreign Policy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994),

172–75; and Rebecca U. orpe, e American Warfare State: e Domestic Politics of Military Spending

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 9

enacted appropriations, it excludes both authorizing legislative activity and House and

Senate interim decisions preceding nal enactment.

14

e authors made certain technical modications to the data to account for irregu-

lar reporting practices used in the nal years of the Budget Control Act, the law that

capped defense budgets from FY 2012 to FY 2021, specically with respect to funding

for Overseas Contingency Operations. Skipping these corrections or performing them

dierently does not change the central ndings.

Altogether, the dataset consists of nearly 10,000 observations, a gure that excludes

the arithmetical and ination manipulations required to generate the results. Al-

though the dataset does not include every line item contained in the DoD appropria-

tions bill, it provides a sucient body of evidence for the article’s analysis.

Congressional Adjustments to DoD Funding Requests,

2016 to 2023

Over the past 75 years, Capitol Hill has not reexively given the Pentagon whatever

it asked for, refuting the negligible hypothesis. From FY 1950 to FY 2023, Congress

subtracted from DoD’s base budget request three times more oen than it added to

the request.

15

Understanding this historical thriiness illuminates the anomaly of re-

cent years in which Congress approved signicantly larger base budgets than the De-

partment of Defense requested. Congress has overridden the Department with such

generosity only twice before. Once was during President John F. Kennedy’s rst year

controlling the budget (FY 1962), as the young president maneuvered to fulll his

campaign pledge to eliminate a “missile gap” with the Soviet Union.

16

e second was

during one of the most intense phases of the war in Iraq (FY 2006 and FY 2007).

14. Robert J. Art, “e Pentagon: e Case for Biennial Budgeting,” Political Science Quarterly 104, no.

2 (Summer 1989); Mackubin T. Owens, “Micromanaging the Defense Budget,” Public Interest 100 (Sum-

mer 1990); and Paul Stockton, “Beyond Micromanagement: Congressional Budgeting for a Post- Cold War

Military,” Political Science Quarterly 110, no. 2 (Summer 1995).

15. Linwood B. Carter and omas Coipuram Jr., Defense Authorization and Appropriations Bills:

FY1970–FY2006 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service [CRS], November 8, 2005), 29–30,

https://apps.dtic.mil/; Barbara Salazar Torreon and Soa Plagakis, Defense Authorization and Appropria-

tions Bills: FY1961–FY2021 (Washington, DC: CRS, July 12, 2021), 39, https://crsreports.congress.gov/;

and Sharp, Inconsistent Congress, 15.

16. Travis Sharp, “Wars, Presidents, and Punctuated Equilibriums in US Defense Spending,” Policy

Sciences 52, no. 3 (September 2019): 386–89.

10 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

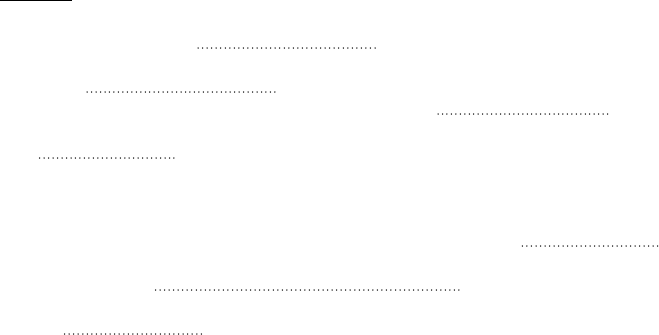

Figure 1. Congressional adjustment to president’s budget request as report-

ed in enacted DoD appropriations bill, by appropriation subtitle (FY23 $ bil-

lions, excluding supplementals).

17

Since FY 2016, Congress has not concentrated its spending adjustments in military

personnel and O&M, the appropriation titles that receive the most funding (g. 1).

Instead, it has emphasized procurement and RDT&E. is nding thus rebuts the s-

cal hypothesis. From FY 2016 to FY 2023, Congress added $79 billion for procure-

ment above the administration’s requests. (e article reports all budgetary gures in

FY 2023 constant dollars). at $79 billion gure is 1.4 times greater, in absolute value

terms, than the adjustments made to the three other accounts combined. Congress

added nearly 40 percent of that extra $79 billion in FY 2022 and FY 2023 following

the expiration of the Budget Control Act.

is procurement push likely reected a desire to compensate for years of smaller-

than- preferred hardware budgets.

18

Lawmakers perhaps also reasoned that under-

funding military personnel, and thereby freeing up funds for procurement additions,

17. Sharp, Inconsistent Congress, 18–19.

18. Eric Edelman et al., Providing for the Common Defense: e Assessment and Recommendations

of the National Defense Strategy Commission (Washington, DC: DoD, November 2018), 54–56, https://

www.usip.org/.

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 11

was warranted because recruiting shortfalls resulted in personnel costs being smaller

than expected.

19

Regardless of the rationale, however, previous studies have reported a

similar congressional preoccupation with procurement, so the nding here rearms

an enduring trend, not an isolated response to contemporary circumstances.

20

Over-

all, the data show that Congress has continued its long- running pattern of using pro-

curement increases as a preferred tool for shaping the US military, supporting the

programmatic hypothesis.

Although procurement received most of Congress’ largesse, two aspects of RDT&E

spending deserve mentioning. First, the RDT&E budget grew faster than other ac-

counts over the past decade, and the data prove that Congress enabled this central

trend in US defense spending.

21

Second, Congress continued relying heavily on

RDT&E-directed spending requests, commonly known as earmarks, to steer funds to

pet projects.

22

So, even though Congress’ RDT&E additions totaled less than its pro-

curement additions, the former still provided legislators with a powerful way to ad-

vance their priorities in line with the programmatic hypothesis.

Congress’ recent practice of overfunding procurement and RDT&E while under-

funding military personnel and O&M carries risks with defense spending attening

under the Fiscal Responsibility Act. During budgetary downturns since the end of the

Cold War, hardware funding has oen received preferential treatment, at least accord-

ing to the crude metric of absolute dollars. In years since FY 1992, when defense

spending remained at or declined in real terms, military personnel and O&M fund-

ing reductions exceeded procurement and RDT&E reductions 71 percent of the time

by an average margin of $18 billion.

23

e portion of defense spending dedicated to military personnel plus O&M has

declined modestly since FY 1992, so Congress has not been simply cutting more from

a growing spending area, contradicting the scal hypothesis. is 30-year trend re-

verses the pattern from the Cold War, when procurement plus RDT&E reductions

were usually larger and procurement oen functioned as a “slack variable” by absorb-

ing disproportionate cuts during budgetary downturns.

24

Readiness shortfalls have oen intensied in those years with at budgets and

larger cuts to military personnel and O&M, particularly when that outcome repeated

19. omas Novelly et al., “Big Bonuses, Relaxed Policies, New Slogan: None of It Saved the Military from

a Recruiting Crisis in 2023,” Military.com, October 13, 2023, https://www.military.com/.

20. Kanter, “Congress,” 131–32; Korb, “Congressional Impact,” 54–55; and Daniels and Harrison, “As-

sessing the Role,” 8–9.

21. Sharp, Inconsistent Congress, 3.

22. John M. Donnelly, “Hill- Favored Projects Called Defense Budget’s ‘Black Hole,’ ” Roll Call, May 23,

2023, https://rollcall.com/.

23. DoD, National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2024 (Washington, DC: CRS, May 2023), Table

6-8, 138–145, https://comptroller.defense.gov/.

24. Kevin N. Lewis, National Security Spending and Budget Trends since World War II (Santa Monica,

CA: RAND Corporation, 1990), 81, 109, https://www.rand.org/.

12 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

itself over multiple years, as happened during the mid-1990s and early-2010s.

25

In

general, underfunding military personnel and O&M can degrade military prepared-

ness in many ways, including by diminishing support for service members, reducing

training opportunities, and constraining equipment maintenance.

26

Today, the Air

Force and Navy are suering from several of these problems, with reduced ying

hours and inadequate maintenance infrastructure, respectively, representing areas of

special concern.

27

Congress could mitigate these diculties with funding increases, but under con-

strained budgets, those additions would have to come at the expense of procurement

add- ons. Continuing to add procurement funds risks exacerbating readiness chal-

lenges by forcing the US military to possess equipment that it did not request, creating

larger- than- anticipated bills for the personnel, training, and maintenance needed to

operate that equipment.

To be clear, the argument here is not that distributing cuts equally across appro-

priation titles constitutes a strategically optimal response to contracting budgets. Such

an approach is awed because it fails to incorporate assessments of both the probabil-

ity of war erupting and the US military’s standing relative to potential adversaries. By

the same logic, however, privileging hardware over military personnel and O&M, re-

gardless of shiing war risks and power balances, represents an equally unsound ap-

proach. In the budget- constrained years ahead, Congress’ willingness to forswear add-

ing funds for hardware when necessitated by international developments, and instead

allocating those funds to invest in readiness and other deserving areas of the Joint

force, will prove essential to producing a US military that is as prepared as possible to

defend the nation’s interests across the globe.

From FY 2016 to FY 2023, Congress concentrated its spending adjustments in fa-

vored and disfavored investment areas, precisely as the programmatic hypothesis pre-

dicts. Five appropriation subtitles emerged as clear congressional favorites, receiving

among the largest increases in both dollar and percentage terms: Navy shipbuilding

and conversion, Navy aircra procurement, Air Force aircra procurement, Army

RDT&E, and Army aircra procurement.

Although Congress clearly preferred adding money for procurement and RDT&E,

not military personnel and O&M, it did subtract funds from multiple procurement

subtitles, including several missile and ammunition accounts. For example, it cut the

25. Jerre Wilson and Michael E. O’Hanlon, Shoring Up Military Readiness (Washington, DC: Brook-

ings Institution, January 1999), https://www.brookings.edu/; and Robert Hale, Budgetary Turmoil at the

Department of Defense from 2010 to 2014: A Personal and Professional Journey (Washington, DC: Brook-

ings Institution, August 2015), 4–9, https://www.brookings.edu/.

26. Todd Harrison, “Rethinking Readiness,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 8, no. 3 (Fall 2014): 42–44.

27. Dakota L. Wood, 2024 Index of U.S. Military Strength (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation,

2024), 456–59, 492–99, https://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/; Military Readiness: Improvement in Some

Areas, but Sustainment and Other Challenges Persist, GAO-23-106673 (Washington, DC: Government Ac-

countability Oce, May 2, 2023), https://www.gao.gov/; and Michael P. DiMino and Matthew C. Mai, “e

US Military Has a Readiness Problem,” Stars & Stripes, October 24, 2023, https://www.stripes.com/.

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 13

Air Force’s missile procurement requests by an average of 5 percent (~$140 million)

per year in real terms. e fact that Congress underfunded munitions purchases, de-

spite their residing in the favored procurement account, demonstrates a selectivity

consistent with the programmatic hypothesis rather than the indiscrimination associ-

ated with the scal hypothesis.

In terms of policy implications, the underfunding of munitions indicates Congress

shares responsibility for the disappointing state of the US munitions industrial base

revealed by ongoing American support for Ukraine.

28

Without steadier congressional

support for munitions procurement, the US military will face serious problems in any

future war against a peer adversary.

29

Digging even deeper into line- item data for the ve favored subtitles, Congress

added funds for favored investments in line with the programmatic hypothesis, al-

though some evidence also exists for the scal hypothesis. Congress increased spend-

ing on preferred programs, in particular unmanned aircra systems (UAS) across the

services, Army rotary wing aircra, Navy surface and expeditionary vessels, and Air

Force C-130s. e extra resources absorbed by these programs, measured in both dol-

lar and percentage terms, conrms their status as congressional darlings, a result also

reported in previous research.

30

Of course, DoD budgetary gamesmanship potentially aected the observed out-

comes. e Pentagon may have knowingly reduced its budget requests for certain pro-

grams anticipating that Congress would add funding during the appropriations pro-

cess. Additionally, any favoritism in Congress’ allocation of classied funds cannot be

addressed by this unclassied analysis.

Judging whether the favored programs deserved Congress’ budgetary largesse un-

der the current US defense strategy is another matter entirely. On the one hand, the

funding increases provided to UAS oer a clear example of Congress embracing

newer technologies critical to US strategy, particularly since military service support

for several of these systems has proven uneven at best.

31

On the other hand, Congress’ generous funding of helicopters and C-130s, among

others, shows its preference for supporting established weapons systems. ese types of

programs potentially lack the compelling operational need justifying hey budgetary

28. Stacie Pettyjohn and Hannah Dennis, Precision and Posture: Defense Spending Trends and the FY23

Budget Request (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security [CNAS], November 2022), https://

s3.us- east-1.amazonaws.com/; Pettyjohn and Dennis, “Production Is Deterrence”: Investing in Precision-

Guided Weapons to Meet Peer Challenges (Washington, DC: CNAS, June 2023), https://s3.us- east-1

.amazonaws.com/; and Tyler Hacker, “Money Isn’t Enough: Getting Serious about Precision Munitions,”

War on the Rocks, April 24, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/.

29. Tyler Hacker, Beyond Precision: Maintaining America’s Strike Advantage in Great Power Conict

(Washington, DC: CSBA, June 2023), https://csbaonline.org/.

30. Daniels and Harrison, “Assessing the Role,” 17.

31. Valerie Insinna, “Get Ready for Another Fight over the Future of the MQ-9 Reaper,” Defense News,

May 26, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/.

14 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

increases, especially given the opportunity costs of funding them.

32

In a March 2023

statement before the House Armed Services Committee, for instance, General Jacque-

line Van Ovost, commander of US Transportation Command, testied that the current

C-130 inventory remains adequate for meeting airli requirements in the near future.

33

at said, it remains dicult to make unassailable judgments about the operational rel-

evance of specic weapons given the unpredictability of the future strategic environment.

Congressional committee assignments do not fully explain Capitol Hill’s preference

for established weapons systems. Air Force C-130s illustrate the point. Since FY 2016,

the C-130 and EC-130 programs received increases of 84.5 percent and 85.1 percent,

respectively, over the Defense Department’s aggregate requests. From FY 2018 to FY

2023, Congress provided the Air Force with an additional $6.3 billion for the procure-

ment of C-130J aircra—a nearly 1,825 percent increase from the Defense Depart-

ment’s requested amount of $347 million.

Yet, the legislator whose district features the main C-130 plant, Representative

Barry Loudermilk (R- Georgia), has never served on a committee relevant to C-130

acquisition.

34

C-130 contractors, supply chains, and basing locations are spread

throughout the United States, fortifying its political support, but the same is true for

other programs such as the F-35 that received only a 10.8 percent congressional in-

crease over the Defense Department’s aggregate requests. Ultimately, the C-130’s re-

cent budgetary success likely has resulted from Air National Guard and industry lob-

bying, the aircra’s broad range of uses, and Congress’ decades- long love aair with

the program. ese three factors, though more complex, oer more explanatory

power than the notion of a small cabal of legislators sitting on the right committees

who control the program’s destiny.

35

Two patterns in Congress’ spending adjustments indicate a more scal than pro-

grammatic orientation. First, Congress regularly reduced spending on programs

viewed as underperforming or overfunded, including the Army’s RQ-11 UAS and

Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense Elevated Netted Sensor System (JLENS)

blimp; the Navy’s Infrared Search and Track (IRST) and carrier refueling and overhaul

programs; and the Air Force’s KC-46A refueling tanker. In each of these cases, Con-

gress justied its cut by invoking program management factors such as cost growth,

acquisition plan modications, accidents, production quality shortcomings, and

schedule delays. In no cases reviewed by the authors did Congress justify the reduc-

tion by citing a given program’s lack of relevance to US defense strategy.

32. Jan Tegler, “Air Force under Pressure as Airli Capacity Falls,” National Defense, June 3, 2022,

https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/,

33. Joint Readiness and Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee Hearing: Posture and Readiness

of the Mobility Enterprise – TRANSCOM and MARAD, Hearings before the House Armed Services Commit-

tee, 118th Congress (2023) (statement of General Jacqueline D. Van Ovost, commander, US Transporta-

tion Command, United States Air Force), https://www.ustranscom.mil/.

34. Ballotpedia, s.v. “Barry Loudermilk,” accessed July 27, 2023, https://ballotpedia.org/.

35. Frank R. Baumgartner et al., Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why (Chi-

cago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 15

is rst pattern reveals an irony in congressional defense budgeting. Although

Congress displays a programmatic orientation driven by strategy or parochialism or

both, it generally justies its decisions in scal terms using the language of eciency

and stewardship of taxpayer dollars. As a result, scal rationales function as a shield

for Congress to make decisions that are presumably rooted in programmatic consid-

erations of one kind or another.

Second, in areas such as Army RDT&E and Navy aircra procurement, Congress

distributed its spending increases across a wide variety of programs, a pattern also

more consistent with the scal hypothesis. Many of these investments supported wor-

thy programs, but Congress’ failure to make more decisive choices, particularly with

Army RDT&E, indicates a tendency to spread extra money around rather than mak-

ing informed bets on a handful of key programs.

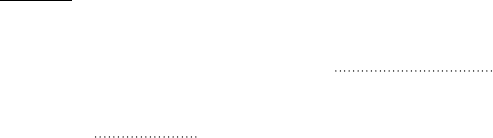

Surveying congressional spending adjustments over time brings two insights into

sharper relief (g. 2). First, congressional adjustments did not discernibly change fol-

lowing the release of the 2018 National Defense Strategy, an important document that

codied the Defense Department’s intention to prevail in great power competition.

Congress reoriented aspects of its legislative agenda aer the strategy appeared, to be

sure, but that reorientation did not register clearly in the budgetary outcomes analyzed

here. In fact, some congressional adjustments seemingly contradicted the strategy.

For instance, steady congressional increases for defense- wide and Army RDT&E

contrasted with volatile adjustments for Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps RDT&E.

e strategy called for implementing technological advancements across the Joint

force, of course, but it emphasized elding forces capable of striking diverse targets

inside enemy air and missile defense networks—a capability typically associated with

air and naval forces.

36

Although the size of congressional adjustments does not necessarily reect their

quality, Congress did not provide the type of steady RDT&E increases for air and na-

val forces that one might expect given the strategy. Of course, it is possible that Con-

gress identied fewer deciencies with air and naval RDT&E requests and thus had

fewer reasons to add funds. Still, the diering treatment of RDT&E budgets across

components provides at least suggestive evidence for the programmatic hypothesis.

36. James N. Mattis, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America:

Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge (Washington, DC: DoD, January 2018), 6, https://

dod.defense.gov/.

16 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

Figure 2. Congressional adjustment to president’s budget request as re-

ported in enacted DoD appropriations bill, appropriation titles, and selected

subtitles by year (FY23 $ billions, excluding supplementals).

37

Second, some congressional spending additions exhibited the across- the- board or

balanced character associated with the scal hypothesis. e appropriation titles and

Air Force procurement charts in gure 2, for example, depict balanced growth rates

across dierent spending categories, a sign of Congress doling out proportional in-

creases while still favoring certain categories in dollar terms. Yet the procurement by

department chart oers a counterexample of Congress bestowing faster- growing in-

creases on the Air Force than on other departments. Overall, although the balance of

evidence supports the programmatic hypothesis, Congress is still prone to making

scal- style adjustments in certain areas.

Conclusion

is article demonstrates that Congress continues to exhibit a largely program-

matic orientation toward defense spending characterized by overfunding procure-

ment and RDT&E while underfunding military personnel and O&M. e article’s

analysis of spending adjustments since 2016 show that congressional action signi-

cantly aects the defense budget’s size and shape, refuting the negligible hypothesis,

37. Sharp, Inconsistent Congress, 20–21.

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 17

and it displays discernible preferences across programs, undercutting the scal hy-

pothesis. e central policy problem identied by the article involves whether Con-

gress can stave o its hunger for hardware and steer funds into other parts of the Joint

force, when needed, to maximize US military preparedness under the constrained

budgets of the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

e Department of Defense and Congress both shape defense budget outcomes,

and both institutions should take steps to improve their handling of American defense

policy in the challenging years ahead. If they do not, the US military may nd itself

less prepared to compete eectively against China and Russia while protecting

broader American interests around the world.

e Defense Department should nd better ways to persuade Congress to support

capabilities viewed as essential to warghting success. For starters, senior defense of-

cials should communicate precise, tangible, and specic rationales for the minimum

investments needed in each spending account. ey should express these rationales to

Congress in compelling, jargon- free, plain English that makes their force requirements

clear—a departure from the Department’s tendency to bury its recommendations in

technocratic language that can inadvertently obscure the existence of risk.

38

As retired

Air Force Lieutenant General David Deptula concluded recently, “Making better-

informed decisions about the acceptability of risk and, by extension, what should be

done about it requires better communication among all relevant stakeholders.”

39

e Department of Defense should also recognize that Congress possesses a pro-

grammatic orientation and thus will never approve exactly what the Pentagon requests,

though clearer communication by the Pentagon will help shape congressional desci-

sions. As a result, defense planners must develop operational concepts that enable the

US military to ght and win using what Congress has provided. If senior ocials judge

they cannot accomplish the mission with the resources provided, then they must let

Congress know. Yet senior ocials should also avoid letting the perfect become the

enemy of the good by a disproportionate focus on what Congress withholds, and in-

stead concentrate on making ecient and eective use of what is provided.

As an atomistic institution lacking the Defense Department’s hierarchical structure,

Congress depends on individual lawmakers to achieve policy outcomes. Consequently,

any lasting improvements in Congress’ handling of the defense budget will only come

from actions taken by individual policy entrepreneurs who synthesize politics, problems,

and policies to create meaning for other lawmakers trying to navigate the oen intimi-

dating ambiguity of defense policymaking.

40

A skilled policy entrepreneur not only must

38. ane C. Clare, “Networking to Win: Mission Prioritization for Wartime Command and Control,”

War on the Rocks, January 15, 2024, https://warontherocks.com/; and Peter C. Combe II, Benjamin Jensen,

and Adrian Bogart, Rethinking Risk in Great Power Competition (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and

International Studies, February 2023), 4–8, https://www.csis.org/.

39. David A. Deptula, “Managing Risk in Force Planning,” in 2022 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed.

Dakota L. Wood (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation, 2022), 30, https://www.heritage.org/.

40. Nikolaos Zahariadis, Ambiguity and Choice in Public Policy (Washington, DC: Georgetown Uni-

versity Press, 2003), 19–22.

18 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Hardwired for Hardware

act outside their political self- interest with some regularity but also must know more

about the policy process than any of their colleagues.

41

Expanding Capitol Hill’s pipeline of defense policy entrepreneurs has never been

easy, and today’s fractured politics present additional diculties. Yet opportunities do

exist to make progress. In the mid-1970s, Representative Les Aspin (D- Wisconsin),

then a newly elected congressman who later became a leading defense policy entre-

preneur of his generation, penned a series of insightful articles about Congress’ role in

defense policy and budgeting.

Aspin’s main advice was that legislative policy entrepreneurs should focus on im-

plementing procedural changes that indirectly shape decision- making processes to

produce better outcomes more of the time. Emphasizing procedure plays to Congress’

strengths because, as he observed, “Making decisions on the basis of rational argu-

ment requires confronting the issues directly, and Congressmen, who are pressured

from all sides, who are continually short of time, and who suer from lack of exper-

tise, are not likely to do that.”

42

In short, skillful legislators use procedure to get what

they want through subtlety rather than confrontation.

Procedural expertise and subtlety are virtues in short supply on Capitol Hill today,

but they still oer the best hope of improving congressional defense budgeting. Poten-

tial procedural rearrangements available to Congress include changing executive

branch reporting relationships, mandating the establishment of certain facts before

actions can occur, designating who can make decisions, and bringing outside groups

or new groups into decision processes.

43

Of these options, mandating the establishment of facts prior to action appears es-

pecially promising. Such mandates, if designed properly, would force senior defense

ocials to present the type of clear, tangible, and specic assessments described in

order to satisfy DoD budget requests. e goal here would not be to burden the

Defense Department with additional pro forma reporting requirements. Rather, it

would be to create categorically dierent requirements whereby senior DoD leaders

must deliver plain- English justications for advancing preferred programs in hopes

of convincing a critical mass of lawmakers to approve them.

Establishing facts prior to action should happen when DoD leaders testify before

Congress on their annual budget requests; however, that process has devolved into

duplicative hearings characterized by an excess of indecipherable jargon making it of

questionable value to Congress, the Department of Defense, or the American public.

Excising a signicant portion of these unproductive annual posture testimonies

and replacing them with a smaller number of more consequential and comprehensible

sessions dedicated to assessing the Department’s progress on important initiatives

would generate far more useful information for Congress to make decisions. Such

41. Zahariadis, 21–22, 166.

42. Les Aspin, “e Defense Budget and Foreign Policy: e Role of Congress,” Daedalus 104, no. 3

(Summer 1975): 165.

43. Les Aspin, “Why Doesn’t Congress Do Something?,” Foreign Policy 15 (Summer 1974): 78–80.

Sharp & Nicastro

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 19

information will not eliminate the challenges created by Congress’ programmatic ori-

entation, but it stands a reasonable chance of helping Congress improve the coherence

and eectiveness of US defense policy by funding programs consistent with the Na-

tional Defense Strategy and DoD missions. Æ

20 ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER

Spacepower and Strategy

SPACE AND WAR IN

UKRAINE

Beyond the Satellites

robiN DiCkey

MiChael p. GleasoN

Much of the international attention on the use of space in Russia’s war in Ukraine—

commercial space services in particular—has focused on satellite capabilities while ignor-

ing the signicance of other aspects of space systems, such as ground infrastructure, so-

ware, and information- sharing practices. Although Russia has numerous military satellites

while Ukraine has none, international and commercial space information sharing and

innovations in terrestrial hardware and soware have allowed Ukraine to exceed Russia in

the use of space at the operational, strategic, and diplomatic levels. e US armed forces

can learn policy, strategy, and doctrine lessons including the importance of robust space

doctrine; decentralized, strategic information sharing; and the need to protect the ground

and communications segments of space systems.

S

pace has played a highly visible role in Russia’s war in Ukraine since and even

before Russia’s invasion in February 2022. Satellite images of Russian troop con-

voys and destroyed Ukrainian buildings have provided the backdrop informing

international perspectives of the war, while space data and services have directly sup-

ported warghters on the ground. Many observers have begun to refer to the war in

Ukraine as the “rst commercial space war,” paralleling descriptions of the 1991 Gulf

War as the “rst space war.”

1

Satellites themselves are usually the focus in discussions on military uses of space.

Yet, satellite ground systems, satellite data processing soware, decentralized informa-

tion sharing, and novel applications of data from existing satellite capabilities by

troops on the ground have transformed the value and use of space, especially for

Ukraine and its allies. Russia has failed to capitalize on a clear lead in number and

Robin Dickey, a member of the technical staff at The Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy,

holds a master’s degree in international studies, concentrating in strategic studies, from the Johns Hopkins School

of Advanced International Studies.

Dr. Michael Gleason is a national security senior project engineer in The Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space

Policy and Strategy.

1. Sandra Erwin, “On National Security: Drawing Lessons from the First ‘Commercial Space War,’ ”

SpaceNews, May 20, 2022, https://spacenews.com/; and Jonathan Beale, “Space, the Unseen Frontier in the

War in Ukraine,” BBC, October 5, 2022, https://bbc.com/.

Dickey & Gleason

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 21

quality of satellites over Ukraine, which owned and operated no national satellites

when Russia invaded. e underwhelming eects of Russia’s initial, perceived space

superiority indicate that space lessons learned from its war in Ukraine should also include

the importance of space doctrine, information- sharing processes, and ground- based en-

abling segments beyond the satellites—whether commercial or government- owned.

e networked, distributed approach to using and sharing information from space

pursued by Ukraine and its allies has demonstrated the asymmetric advantages of this

approach compared to the centralized, hierarchical structure used by Russia. Russian

forces have struggled to both collect sucient tactically useful information from satel-

lites and disseminate that information to warghters in a timely manner, due to their

rigid command structure.

Ukrainian forces on the other hand have been able to innovate and adapt with

more decentralized command and control (C2) and more direct communications and

coordination between tactical units. is has increased the demand for data process-

ing architectures able to process and disseminate much larger amounts of data to a

much larger number of recipients, a burden that could be considered and addressed in

future US architectures and strategies. is article explores the uses of space in Rus-

sia’s war in Ukraine and how innovations beyond those involving the satellite per-

forming the mission have shaped the battleeld, providing some preliminary lessons

for the United States’ uses of space across the Joint force in future conicts.

Components of Space Systems

Space systems can typically be broken down into three segments: (1) the space seg-

ment, or the satellites performing the mission; (2) the ground segment, or the systems

and personnel on Earth that operate the satellites and the facilities that receive, pro-

cess, and distribute data from satellites; and (3) the “link” segment, or the signals that

connect the satellites to each other and to users and operators on the ground through

data uplinks to the space segment and data downlinks back to the ground segment.

2

Each of these segments is vital to the collection and dissemination of data so that ne-

glecting any one segment diminishes the value of the others.

While satellites—the space segment—are usually what come to mind when think-

ing about space systems, the ground segment, link segment, and enabling soware

expand the denition of space systems far beyond the objects in orbit. e ground

segment can be subdivided into satellite command and control (C2) on the one hand

and the end- user segment on the other. For satellite C2, ground stations send com-

mands to and can receive updates and data from satellites, and for the end- user seg-

ment, individual- level systems such as mobile terminals, antennas, receivers, and

transmitters can provide interfaces between satellites and users in the eld. Figure 1

represents the three major segments.

2. Air Command and Sta College Schriever Space Scholars, Air War College West Space Seminar,

AU-18 Space Primer (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 2023), https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/.

22 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Space and War in Ukraine

Figure 1. Space system segments

Satellite Capabilities Supporting Ukraine and Its Allies

At the onset of the Russian invasion, Ukraine did not own or operate any satellites;

however, the United States and its NATO Allies have made space support available in

various forms. Commercial actors have also provided a historic degree of space ser-

vices to Ukraine. As a result, Ukraine has been able to leverage space systems far be-

yond expectations based on its capabilities prior to February 2022, which did not in-

clude independent access to space. While signicant public attention has been

directed at Ukraine’s success in using commercial space services at the tactical level,

space- based systems have also had notable operational- and strategic- level eects.

Position, Navigation, and Timing

Ukraine uses satellite services provided by the US military, most notably, GPS

position, navigation, and timing (PNT) signals. GPS signals enable a wide range of

precision strike rockets, bombs, and artillery shells used by Ukrainian forces.

3

At

the operational and strategic levels, GPS has been the NATO standard for PNT for

decades.

4

As Ukraine depletes its stocks of Soviet/Russia- sourced military equip-

ment, and as NATO countries rearm Ukraine with NATO standard weapons,

3. Beale, “Unseen Frontier.”

4. Tim Vasen, “Is NATO Ready for Galileo?,” Journal of the JAPCC [Joint Air Power Competence Cen-

tre] 28 (December 2019), https://www.japcc.org/; and Michael P. Gleason, “Galileo, Power, Pride, and

Prot” (Ph.D. diss., George Washington University, January 31, 2009), 97, 215, https://apps.dtic.mil/.

Dickey & Gleason

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 23

Ukraine may rely more upon GPS. Although there are alternatives to GPS, such as

the European Galileo system, open- source reporting on the conict does not sug-

gest if or how they are being used.

Electro- optical and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Imagery

Before the February 2022 invasion, Ukraine beneted in several ways from US na-

tional security satellites. Imagery satellites provided intelligence to US national- level

leadership, enabling the Biden administration to condently raise the alarm globally

about Russia’s intentions and alert Allies to the threat. US- furnished strategic intelli-

gence made its way to NATO eld commands prior to the invasion, and the Alliance

deployed additional forces in the region.

5

Once the ghting began, US national security

Earth observation and electronic signals intelligence helped ll the intelligence gaps as

the US military pulled its surveillance planes back from international airspace near Rus-

sia’s borders and the Black Sea.

6

Commercial remote- sensing satellites include those capable of collecting high-

resolution, electro- optical imagery and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery. SAR

imagery, although not collected by as many satellites and operators as electro- optical

imagery, has the unique benet of functioning even in low- visibility conditions, such

as nighttime or cloudy weather. Commercial satellites help track buildups of Russian

forces and troop movements within Ukraine and in Russia and Belarus. e availabil-

ity of various kinds of imagery has helped Ukraine accurately locate, track, and target

Russian forces prior to strikes and conduct battle damage assessments aerwards,

which has in turn helped improve the eciency and conservation of ammunition.

7

Journalists and nongovernmental organizations have used satellite imagery creatively

to reveal war crimes committed by Russia. Commercial companies such as Maxar,

Planet, and BlackSky have directly contributed to this activity by providing images to

these entities.

8

ese collaborations have been used to map mass graves, the systematic

looting and destruction of cultural heritage sites, the forced adoption and re- education

5. Garrett Reim, “Lessons from War in Ukraine from Former USAFE Commander,” Aviation Week

Network, December 6, 2022, https://aviationweek.com/; and W. J. Hennigan, “U.S. Deploys Forces in Re-

sponse to Putin’s Ukraine Moves,” Time, February 22, 2022, https://time.com/.

6. Reim.

7. David Ignatius, “How the Algorithm Tipped the Balance in Ukraine,” Washington Post, December 19,

2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/; Steve Rosenberg and Jaroslav Lukiv, “Ukraine War: Drone Attack

on Russian Bomber Base Leaves ree Dead,” BBC, December 26, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/; Anna

Ahronheim, “Russian Bombers Capable of Carrying Nukes Detected near Finland,” Jerusalem Post, Septem-

ber 30, 2022, https://www.jpost.com/; and Egle E. Murauskaite, “U.S. Military Assistance to Ukraine in 2022:

Impact Assessment,” Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA), SMA EUCOM Speaker Series, livestreamed

presentation, March 15, 2023, YouTube recording, 1:01:47, https://www.youtube.com/.

8. Denise Chow and Yuliya Talmazan, “Watching from Space, Satellites Collect Evidence of War

Crimes,” NBC News, May 3, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/.

24 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Space and War in Ukraine

of Ukrainian children in camps, the systematic destruction of food production and stor-

age capacities, and the targeted destruction of health and education facilities.

9

Satellite Communications

Ukraine uses several commercial satellite communication (SATCOM) systems for

a wide variety of purposes. In the opening days of the conict, Ukrainian President

Volodymyr Zelensky stayed in regular contact with the United States even while mo-

bile, using a secure satellite phone that the White House had given the Ukrainian gov-

ernment before the invasion occurred.

10

Iridium, Globalstar, and Inmarsat all have

capabilities in that sector.

11

Zelensky also uses Starlink satellites to directly address Ukrainians, national parlia-

ments, and international organizations around the world. Commercial telecom satel-

lites enable Ukrainians to stay connected with each other as well. e Luxembourg-

based satellite operator SES broadcasts most Ukrainian TV channels and has provided

space- based emergency internet and phone services to refugee camps along the

Ukrainian border.

12

Starlink provides broadband internet connectivity for a wide range of military and

civilian users across Ukraine and has been crucial to Ukraine’s battleeld successes.

Starlink satellites provide connectivity enabling secure communication and situational

awareness from top echelons to command bunkers and units in the eld.

13

On the

battleeld, Ukrainian warghters have used internet connectivity provided by Starlink

as a key communication method for a wide range of activities as they nd, target, and

destroy enemy forces.

14

Starlink also enables “tele- maintenance” of US and NATO weapon systems in Ukraine.

When something breaks and Ukrainian forces lack the expertise to repair it, Ukrainian

forces have used Starlink to reach back to US maintenance specialists at a base in Poland.

9. “Recent Reports,” Conict Observatory, accessed on March 1, 2023, https://hub.conictobserva

tory.org/.

10. Kylie Atwood and Zachary Cohen, “US in Contact with Zelensky through Secure Satellite Phone,”

CNN, March 1, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/; “e Phone at Zelensky Uses to Avoid Being Found by

Russia,” Marca, March 16, 2022, https://www.marca.com/; and “Iridium 9575A for U.S. Government,”

Iridium (website), accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.iridium.com/.

11. Ben Gran, “What Is a Satellite Phone?,” SatelliteInternet.com, June 12, 2023, https://www.satelliteinter

net.com/.

12. Pierre Weimerskirch, “SES Supports Ukraine from Space,” RTL Today, March 2, 2022, https://

today.rtl.lu/.

13. Beale, “Unseen Frontier.”

14. Sam Skove, “How Elon Musk’s Starlink Is Still Helping Ukraine’s Defenders,” Defense One, March

1, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/; Nick Allen and James Titcomb, “Elon Musk’s Starlink Helping

Ukraine to Win the Drone War,” Telegraph, March 18, 2022, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/; and Alexander

Freund, “Ukraine Using Starlink for Drone Strikes,” DW (Deutsche Welle), March 27, 2022, https://www

.dw.com/.

Dickey & Gleason

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 25

ese specialists diagnose the problem via video, walk the Ukrainian forces through the

recommended xes, or help put a new part on order directly from the eld.

15

ere have been several challenges involved in relying on Starlink, including public

incidents where SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk questioned on social media

whether Starlink services should continue to be provided to Ukraine.

16

SpaceX’s grow-

ing restrictions on Starlink services within Ukraine have caused concern and driven

some exploration of alternatives.

Other commercial satellite companies provide Ukraine internet connectivity from

space, including Viasat, OneWeb, SES, Iridium, Inmarsat, Eutelsat, and Avanti.

17

Vi-

asat, OneWeb, and SES are all working to build more capacity, including through new

constellations and new agreements with Ukrainian telecom operators.

18

Nevertheless,

Starlink remains the most visible provider of mobile satellite communication services

in Ukraine.

Radio Frequency Monitoring

Some commercial satellites have another relevant capability: the ability to monitor

radio frequency (RF) signals. Commercial space- based RF sensing is useful to detect

jamming of GPS and communication signals and geolocating the jamming’s source.

19

GPS jamming can disrupt many basic services, including transportation networks, air

travel, logistics, and telecommunication. Tracking this interference can help operators

come up with alternatives and work- arounds.

20

For example, in March 2022, the com-

pany HawkEye 360 publicly announced it had “the capability to detect and geolocate

Global Positioning System (GPS) interference, with analysis of data over Ukraine re-

vealing extensive GPS interference activity.”

21

e United States, the European Union (EU), and like- minded nations also use

commercial satellites to help enforce the sanctions imposed on Russia and Russian

individuals. For example, the yachts of individually sanctioned Russian oligarchs have

15. Patrick Tucker, “US Soldiers Provide Telemaintenance as Ukrainians MacGyver eir Weapons,”

Defense One, September 18, 2022, https://www.defenseone.com/.

16. Isabelle Khurshudyan et al., “Musk reatens to Stop Funding Starlink Internet Ukraine Relies on

in War,” Washington Post, October 14, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/.

17. eresa Hitchens, “A Musk Monopoly? For Now, Ukraine Has Few Options outside Starlink for

Battleeld Satcoms,” Breaking Defense, October 19, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/.

18. Hitchens; “OneWeb Conrms Successful Deployment of 40 Satellites Launched with SpaceX,”

Eutelsat OneWeb, press release, January 10, 2023, https://oneweb.net/; Martin Coulter and Supantha

Mukherjee, “Telecom Operator Veon Conrms Deal with British Satellite Firm OneWeb,” Reuters, March

1, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/; and Courtney Albon, “SES Launches Advanced Broadband Satellites

As Military Demand Grows,” C4ISRNet, December 16, 2022, https://www.c4isrnet.com/.

19. Tracy Cozzens, “HawkEye 360 Tech Reveals Early GPS Interference in Ukraine,” GPS World, April 29,

2022, https://www.gpsworld.com/.

20. Cozzens.

21. “Hawkeye 360 Signal Detection Reveals GPS Interference,” Hawkeye 360, press release, March 4,

2022, https://www.he360.com/; and Cozzens.

26 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Space and War in Ukraine

been tracked globally using RF monitoring of onboard ship automatic identication

system transmitters from companies such as Hawkeye 360, Spire, and Kleos Space.

22

Such tracking has enabled the seizure of the yachts when they reach foreign ports.

23

Likewise, the same commercial space companies contribute to tracking cargo ships

that are evading sanctions, documenting the the of Ukrainian grain and enabling

subsequent enforcement actions and future reparations.

24

Space Capabilities beyond Satellites

e robust and diverse satellite capabilities coming to bear in Russia’s war in

Ukraine, especially from the commercial sector, are only a third of the story. Every

service provided by a satellite in orbit is made usable by hardware and soware on

Earth. Innovations in these terrestrial aspects of space systems as well as novel policies

and practices for sharing satellite information have done just as much, if not more,

than the satellite capabilities themselves to provide Ukraine an advantage in the war.

The Ground Segment

Russia’s war in Ukraine has demonstrated both the value and the vulnerability of

the Earth- based aspects of space systems. Modems, terminals, and other ground-

based receivers of satellite communications signals have been highly visible in the

conict. One of the reasons Starlink has been so broadly used at the tactical level is

because the antennas are the size of a pizza box, smaller than those of many other

commercial satellite systems, making them easy to carry by mobile, tactical teams.

25

Mobile satellite ground systems have been vital for replacing the telecommunications

ground infrastructure destroyed by Russia.

Ground segments of space architectures have also become targets. In the hour be-

fore troops moved into Ukraine in February 2022, Russia conducted a cyberattack

that disabled Viasat modems, including terminals used for Ukrainian command and

control. is attack also had international and strategic eects, disabling tens of thou-

sands of ground- based terminals throughout Europe and disrupting wind turbines

22. Tim Fernholz, “Satellites Are Hunting ‘Dark Vessels’ at Evade Sanctions at Sea,” Quartz, Novem-

ber 8, 2022, https://qz.com/.

23. Alessandra Bonomolo and William McLenna, “Inside the Capture of a Russian Oligarch’s Super

yacht,” BBC, November 11, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/.

24. Simão Oliveira, “Grain Laundering: Seeing Who’s Hiding in the Dark Shipping,” Spire (blog), Oc-

tober 26, 2022, https://spire.com/; Michael Biesecker et al., “Russia Smuggling Ukrainian Grain to Help

Pay for Putin’s War,” AP, October 3, 2022, https://apnews.com/; Fernholz, “Satellites”; and Jérôme Weiss,

“Sanctions on Russia As It Presses In on Ukraine,” Spire, April 14, 2022, https://spire.com/.

25. Admin, “David, Goliath, & Space – Is is How Future Wars Will Be Fought?,” Downlink, Produced

by US Defense & Aerospace Report, podcast, 37:12, February 12, 2023, https://defaeroreport.com/; and

Hitchens, “Musk Monopoly?”

Dickey & Gleason

ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC AIRPOWER & SPACEPOWER 27

and internet services.

26

Russia’s action showed how many aspects of infrastructure and

communications in Ukraine and Europe relied on the terminals, while also highlight-

ing a major cyber vulnerability in these ground systems.

27

Unlike the similarities between the threats posed by cyberattacks to ground and

space segments, physical threats can play very dierent roles against the ground seg-

ments of space systems than against the space segments. While physical threats to

satellites are still somewhat limited to either direct- ascent missiles or co- orbital weap-

ons capable of reaching specic orbits, satellite control centers or terminals traveling

with military units can be just as vulnerable to physical attack as any other facility or

materiel on Earth.

Conversely, Ukrainian armed forces have sometimes taken advantage of some of

Russia’s unwitting uses of data from space systems. For example, GPS PNT receivers

are commercially available and ubiquitous around the world, embedded within in-

numerable commercially available products, such as smartphones. Some smartphone

photos taken by Russian forces and posted on social media had embedded GPS-

enabled geolocation data.

28

Ukrainian forces were able to target those GPS coordinates

and destroy Russian forces with precision, using GPS- enabled munitions.

29

The Link Segment

Space does not just connect people to other people; it also connects people to sys-

tems that sense and shoot. Autonomous vehicles and remotely piloted drones are of-

ten guided through satellite communications links, allowing much greater drone

range. At the unit level, Ukrainian forces have leveraged Starlink to relay drone video

feeds directly to artillery batteries in real time, allowing artillery batteries to observe

precisely where their artillery rounds are landing and adjusting re as needed.

30

Re-

connaissance drones using Starlink satellite relays have also enabled coordination of

other ground forces, such as directing soldiers with shoulder- red, antitank weapons

where to position themselves for an attack.

Attack drones that directly target Russian tanks, positions, and other objectives are

also enabled by Starlink.

31

One example is the coordinated drone attack on the Russian

navy at Sevastopol on October 29, 2022. Drones provided real- time intelligence, con-

fused the enemy by creating chaos at the base, and enabled the main explosive- laden

26. Anthony J. Blinken, “Attribution of Russia’s Malicious Cyber Activities against Ukraine,” US De-

partment of State, press release, May 10, 2022, https://www.state.gov/.

27. Katrina Manson, “e Satellite Hack Everyone Is Finally Talking About,” Bloomberg, March 1,

2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/.

28. Stavros Atlamazoglou, “Deadly HIMARS Strikes Show How Ukrainian Forces Are Turning Cell

Phones into ‘Force Multipliers,’ ” Business Insider, January 15, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/.

29. Beale, “Unseen Frontier.”

30. Skove, “Starlink”; and Tamir Eshel, “Coordinated Drone Attack Targets the Russian Black Sea Fleet

at Sevastopol,” Defense Update, October 30, 2022, https://defense- update.com/.

31. Skove; and Freund, “Ukraine.”

28 VOL. 3, NO. 1, SPRING 2024

Space and War in Ukraine

autonomous strike boats to close in on the intended targets. is targeting included a

precision hit on the Admiral Makarov, reportedly the Black Sea Fleet’s new agship aer

themissile cruiser Moskva sank.

32

Yet the direct use of space to enable drones and other military systems has raised

concerns from the commercial operators of such satellite communications networks.

In February 2023, following complaints to the UN by Russia about Starlink’s support

to Ukraine, SpaceX Chief Operating Ocer Gwynne Shotwell expressed opposition to

certain “oensive” uses of Starlink by Ukrainian forces and stated actions were being

taken to restrict those uses.

33

Although the eects or follow- through on that statement are not yet clear in open

sources, this dynamic raises questions of whether certain commercial satellite opera-