2023

National Veteran

Suicide Prevention

Annual Report

VA Suicide Prevention

Oce of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention

November 2023

2

Contents

Introduction 5

Anchors of Hope 5

A Call to Action for Each of You 6

Reviewing Veteran Suicide Within the Context of 2021 6

Key Findings 8

Need for a Whole-of-Nation Public Health Approach to Veteran Suicide Prevention: Themes for Action 10

Organization of Report 13

Part 1: Suicide Among Veterans, 2001–2021 14

Suicide Deaths 14

Average Number of Suicides Per Day 15

Suicide Rates 16

Suicide Rates, by Sex 17

Suicide Rates, by Age 18

Suicide Rates, by Sex and Age 19

Suicide Rates, by Race and Ethnicity 20

Suicide Rates in Year Following Military Separation 22

Method-Specific Suicide Rates 24

Method-Specific Suicide Rates, by Veteran Status and Sex 26

Method-Specific Suicide Rates, by Sex and Veteran status 26

Lethal Means Involved in Suicide Deaths 27

Comparing Suicide Mortality Among Veterans and Non-Veteran U.S. Adults 30

Veteran Leading Causes of Death 34

Years of Potential Life Lost 37

COVID-19 Pandemic: Suicide Surveillance 37

3

Review of Overall Veteran Suicide Data 37

Reflecting Back, Looking Forward: Laying the Foundation for Future

Courses of Action for Suicide Prevention for All Veterans 38

Promote Secure Firearm Storage for Veteran Suicide Prevention 38

Implement and Sustain Community Collaborations Focused Upon Community-Specific

Veteran Suicide Prevention Plans 40

Continue Expansion of Readily Accessible Crisis Intervention Services 42

Improve Tailoring of Prevention and Intervention Services to the Needs,

Issues, and Resources Unique to Veteran Subpopulations 44

Communication and Outreach 44

Community Prevention 44

Research and Innovation 45

Clinical Innovation 46

Part 2: Veterans with VHA or VBA Contact 47

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Health Care 47

VHA Health Care Engagement, 2001–2021 47

Suicide Deaths 48

Suicide Rates 49

Marital Status 52

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Diagnoses 52

Homelessness 55

Veterans Justice Programs 55

Rurality 57

Gender Identity 57

VHA Priority Eligibility Groups 58

Veteran All-Cause Mortality, Overall and by VHA Engagement 61

Leading Causes of Death, for Recent Veteran VHA Users and Other Veterans 62

Recent Veteran VHA Users 62

Other Veterans 63

VA Community Care 64

4

Veterans, by Receipt of VHA and VBA Services 66

VBA Benefit Types Received, Percentage, Among Veterans with VBA Benefits, 2019–2021 68

Suicide Rates Among Veterans by Receipt of VBA or VHA Services 69

Suicide Decedents in 2021: Contacts with VHA and VBA 71

Suicide Decedents, VBA Contact 72

Suicide Decedents with Recent VBA Contact, VBA Services Received 72

Suicide Decedents, Recent Veteran VHA Users with Behavioral Health Autopsy Program Reviews 73

Reflecting Back, Looking Forward: Laying the Foundation for Future

Courses of Action for Suicide Prevention for VHA- and VBA-Engaged Veterans 74

Advance Suicide Prevention Meaningfully into Non-Clinical Support and

Intervention Services, Including Financial, Occupational, Legal and Social Domains 74

Increase Access to and Utilization of Mental Health Services Across a Full Continuum of Care 76

Integrate Suicide Prevention Within Medical Settings to Reach All Veterans 78

Conclusion 81

Appendix A: Brief Summary of 2021 VA Suicide Prevention Initiatives 83

Appendix B: Suicide Prevention Demonstration (Pilot) Projects, FY 2024 86

5

Introduction

This Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) “2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report” provides new

information regarding suicide mortality among Veterans and non-Veteran U.S. adults, from 2001 through 2021,

including the first full year of information since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020. This annual report

of Veteran suicide mortality over time is a critical part of our public health approach to inform next steps in suicide

prevention across the Nation, reflecting on the lives lost and reviewing themes of action to move forward to prevent

suicide. In alignment with prior concerns about the potential for increases in suicide rates with the worldwide COVID-19

pandemic,

1,2

and consistent with trends for the overall U.S. population,

3

this report documents increases in suicide rates in

2021 for Veterans and non-Veteran U.S. adults. Overall reductions in suicide rates among U.S. adults in 2019 and 2020 were

not repeated in 2021. This may reflect a trend in which suicide rates are seen to initially remain stable or diminish during

emergencies and natural disasters, due to a collective “coming together,”

4

followed by increases in rates in ensuing years.

5,6

In 2021, 6,392 Veterans died by suicide, an increase of 114 suicides from 2020. When looking at increases in rates from

2020 to 2021, the age- and sex-adjusted suicide rate among Veterans increased by 11.6%, while the age- and sex-adjusted

suicide rate among non-Veteran U.S. adults increased by 4.5%. Veterans remain at elevated risk for suicide. These

numbers are more than statistics — they reflect Veterans’ lives prematurely ended, which continue to be grieved by

family members, loved ones and the Nation. One Veteran suicide is 1 too many. In this report we reflect on the context

of 2021 and the themes of data which will drive us towards further action for our work together in the mission of suicide

prevention. Our actions are built upon a foundation of hope, and we begin our review reflecting first upon these anchors

for our future work together.

Anchors of Hope

Hope is essential to life and hope serves an important role within suicide prevention efforts. Within the challenges faced

in 2021, key areas of hope emerged, including:

• From 2020 to 2021:

• Suicide rates fell by 8.1% for Veteran men aged 75-years-old and older.

• Among Recent Veteran Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Users

7

between ages 55- and 74-years-old, the

suicide rate fell by 2.2% overall (-0.6% for men, -24.9% for women).

• Among male Recent Veteran VHA Users, suicide rates fell by 1.9% for those aged 18- to 34-years-old.

1

Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. 2020. Suicide Mortality and Coronavirus Disease 2019—A Perfect Storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 77(11), 1093-1094.

2

Banerjee D, Kosagisharaf JR, Rao TSS. 2021. ‘The Dual Pandemic’ of Suicide and COVID-19: A Biopsychosocial Narrative of Risks and Prevention.

Psychiatry Research. 295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113577

3

Garnet MF, Curtin SC. 2023. Suicide Mortality in the U.S., 2001–2021. CDC National Center for Health Statistics, Data Brief 464.

4

These may have fragmented protective feelings of social integration that commonly follow elections. See: Classen TJ, Dunn RA. 2010. The Politics of

Hope and Despair: The Effect of Presidential Election Outcomes on Suicide Rates. Soc Sci Q. 91(3): 593–612.

5

Horney JA, Karaye IM, Abuabara A, Gearhart S, Grabich S, Perez-Patron M. 2020. The Impact of Natural Disasters on Suicide in the United States,

2003–2015. 42(5):328-334. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000723.

6

Kolves K, Kolves KE, De Leo D. 2013. Natural Disasters and Suicidal Behaviours: A Systematic Literature Review. 146(1):1-14.

7

Recent Veteran VHA Users are defined as Veterans who were alive at the start of the year and who received inpatient or outpatient care from VHA

providers in the year or prior year.

6

• Among male Recent Veteran VHA Users, suicide rates fell by 8.6% for those aged 75-years-old and older.

• Among male Veterans not in VHA care who were aged 75-years-old and older, the suicide rate fell by 7.8%.

• From 2001 to 2021:

• The suicide rate among Recent Veteran VHA Users with mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses

fell from 77.8 per 100,000 to 58.2 per 100,000 in 2021.

• Suicide rates fell for Recent Veteran VHA Users with diagnoses of sedative use disorder (-40.4%), depression

(-32.9%), posttraumatic stress disorder (-27.6%) and anxiety (-26.9%).

• Recent Veteran VHA Users rates grew more slowly across 20 years when compared to rates of Veterans

without Recent VHA use. From 2001 to 2021, age-adjusted suicide rates rose 24.5% for male Veterans with

Recent VHA use and 62.6% for male Veterans without Recent VHA use. Age-adjusted suicide rates rose 87.1%

for female Veterans with recent VHA use and 93.7% for female Veterans without Recent VHA use.

• From 2011–2012 to 2020–2021, the suicide rate among Veterans in VHA care with diagnoses related to gender

identity fell from 267.9 per 100,000 person-years to 84.6 per 100,000 person-years.

Hope is the foundation for action in suicide prevention. As we reflect on these anchors of hope, we move to review the

larger context of 2021, laying out a pathway for our course of action for Veteran suicide prevention.

A Call to Action for Each of You

Reviewing Veteran Suicide Within the Context of 2021

This report reflects the complexity of suicide inherent in the Veteran population, and the United States as a whole, in the

context of 2021. Suicide prevention entails numerous and complex risks and protective factors across individual,

relational, community and societal levels.

8

Within 2021, Veterans and the entire U.S. population directly faced health and

mortality effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

9

Weekly U.S. COVID-19 deaths peaked, ebbed, and climbed anew across

2021. By year’s end, over 837,000 Americans had died from COVID-19 since the pandemic began, including over 469,000

Americans who perished from COVID-19 in 2021 alone.

10

In 2020 and 2021, COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death

in the U.S., both overall

11,12

and for Veterans. There were 52,538 Veteran deaths from COVID-19 in 2020, and 60,356 in 2021.

Veteran age- and sex-adjusted all-cause mortality rates were 13.7% higher in 2020–2021 than in 2017–2019.

13

In addition

8

Reed J, Quinlan K, Labre M, Brummett S, Caine ED. 2021. The Colorado National Collaborative: A Public Health Approach to Suicide Prevention. Prev

Med. 152(Pt 1):106501.

9

In September 2021, COVID-19 became the deadliest respiratory pandemic in U.S. history. Lovelace B. CNBC. Covid is Officially America’s Deadliest

Pandemic as U.S. Fatalities Surpass 1918 Flu Estimates. 9/20/2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/20/covid-is-americas-deadliest-pandemic-as-us-

fatalities-near-1918-flu-estimates.html (Accessed 7/2/2023).

10

https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_weeklydeaths_select_00 (Accessed 7/7/2023). Also, in 2021 alone, there were over 2.5 million

COVID-19 hospitalizations in the United States, reaching over 3.6 million from the start of the pandemic through 12/31/2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/

covid-data-tracker/#trends_cumulativehospitalizations_select_00. Despite having substantial prevention resources, U.S. mortality outcomes were

poor relative to other countries. See: Ledesma JR, Isaac CR, Dowell SF, Blazes DL, Essix GV, Budeski K, Bell J, Nuzzo JB. 2023. Evaluation of the Global

Health Security Index as a Predictor of COVID-19 Excess Mortality Standardised for Under-Reporting and Age Structure. BMJ Global Health. doi:

10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012203.

11

Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief, 427. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2021. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/112079/cdc_112079_DS2.pdf (Accessed 6/25/2023).

12

Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, 456. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db456.pdf (Accessed 6/25/2023).

13

Assessed by comparing the average of the annual rates.

7

to these losses, the Nation faced greater financial strain,

14

housing

instability,

15

anxiety and depression levels,

16

barriers to health care and

increased firearms availability, all of which are associated with heightened

suicide risk.

17,18

With the increased purchasing of firearms noted in 2020

and 2021, those who purchased and owned firearms were more likely than

non-firearm owners to report experiencing thoughts of suicide,

19

and

first-time firearm purchasers were more likely to report suicidal ideation.

20

In 2021, potential further distress was experienced by many as a result of

social conflict and political violence.

21

Veteran distress increased from fall

2019 to fall and winter 2020, with evidence of the highest increases in

distress among Veterans aged 18- to- 44-years-old and among women

Veterans. These increases in reported distress were associated with

increasing socioeconomic concerns, greater problematic alcohol use and

decreased community integration.

22

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Veterans were found to experience more mental

health concerns than non-Veterans. A systematic review of 23 studies found increases in the prevalence rates of alcohol

use, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, stress, loneliness and suicidal ideation. The results of this

systematic review found key risk factors to include pandemic-related stress, family relationship strain, lack of social

support, financial concerns and preexisting mental health disorders.

23

14

Data from the 2021 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking indicate that: 1) for both Veterans and non-Veteran U.S. adults,

financial hardships (e.g., lower income, greater debt, residence in economically challenged areas, lack of a rainy day fund) were associated with

poorer physical health, and 2) Veterans more commonly reported financial challenges involving credit card debt and overdraft fees. Personal

communication. 8/7/2023. E. Elbogen, VA National Veterans Financial Resource Center.

15

Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Blakey SM, Wagner HR, Tsai J. 2021. Suicidal Ideation and Thoughts of Self-Harm During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of

COVID-19-Related Stress, Social Isolation, and Financial Strain. Depression Anxiety. 38:739-748.

16

Fischer IC, Na PJ, Harpaz-Rotem I, Krystal JH, Pietrzak RH. 2023. Characterization of Mental Health in US Veterans Before, During, and 2 Years After

the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 6(2):e230463.

17

Monteith LL, Miller CN, Polzer E, Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Iglesias CD, Schneider AL, Brenner LA, Simonetti JA. 2023. “Feel the need to prepare

for Armageddon even though I do not believe it will happen”: Women Veterans’ Firearm Beliefs and Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic,

Associations with Military Sexual Assault and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms. PLOS ONE. 18(2):e0280431. As noted by Monteith and

colleagues, “… it is unclear how women Veterans’ firearm beliefs and behaviors might have changed following 2020, nor whether the pandemic

itself or other relevant societal events (e.g., racial justice protests, political violence) were the predominant drivers of perceptions among any

individual participant.”

18

Miller M, Zhang W, Azrael D. 2022. Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results From the 2021 National Firearms Survey. Annals of

Internal Medicine. 175(2):219-225.

19

Also referred to as suicidal ideation.

20

Anestis MD, Bandel SL, Bond AE. 2021. The Association of Suicidal Ideation with Firearm Purchasing During a Firearm Purchasing Surge. JAMA

Network Open. 4(10):e2132111. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32111.

21

Of note, January 2021 included a single week with the most U.S. COVID-19 deaths of the entire pandemic (25,974 deaths in the week of 1/9/2021

https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_weeklydeaths_select_00); the invasion and looting of the U.S. Capitol by over 2,000 individuals;

impeachment of the former president for inciting insurrection; and the largest increase in the number of firearm purchases in the period from

1/1/2020-4/26/2021 (Miller M, Zhang W, Azrael D. 2022. Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results From the 2021 National

Firearms Survey. Annals of Internal Medicine. 175(2):149-304.) In summer 2021, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan raised additional concerns

as a potential stressor for Veterans. In 2021, conflicting perspectives regarding pandemic responses, social justice, election integrity, and political

violence were in plain view.

22

Fischer IC, Na PJ, Harpaz-Rotem I, Krystal JH, Pietrzak RH. 2023. Characterization of Mental Health in US Veterans Before, During, and 2 Years After

the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 6(2):e230463.

23

Li S, Huang S, Hu S, Lai J. Psychological Consequences Among Veterans During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Psychiatry Research.

2023 Jun;324:115229.

Heavily Impacted Groups in 2021

• Women Veterans

• American Indian or Alaska Native

Veterans

• VHA Veterans

• Homeless Veterans

• Justice-Involved Veterans

8

Simultaneously, VA was moving forward key suicide prevention initiatives in collaboration with other federal agencies,

Veterans Service Organizations (VSO), community partners, non-profit organizations, and others across the Nation

to address the rising needs outlined in 2021. These included the following: Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) 988 preparation;

Suicide Prevention 2.0 (SP 2.0) clinical telehealth expansion; SP 2.0’s Community-Based Intervention for Suicide

Prevention (CBI-SP) growth; Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant Program (SSG Fox SPGP) and

Mission Daybreak development; expansion of special population suicide prevention efforts; and firearm lethal means

safety (LMS) efforts (see Appendix A for a summary). Yet, more work remained for full implementation to occur in each of

the areas.

The context of 2021 challenges for the Nation, and for Veterans specifically, is critical to consider as we review highlights

of this year’s data and outline key courses of action moving forward. Veteran suicide deaths increased by 114 from 2020,

with 6,392 individual Veteran lives lost to suicide in 2021. It is also important to reflect on the subpopulations of Veterans

to identify the unique impacts and potential courses of action to address suicide prevention moving forward. From 2020

to 2021, suicide rates fell by 8.1% for Veteran men aged 75-years-old and older, which may reflect a Nation more fully

focused on connection and support for its more vulnerable individuals during the pandemic. Unfortunately, Veteran

suicide rates increased for other age groups. The increase in Veteran suicides seen in 2021, compared to 2020, was

particularly seen in women Veterans, for whom there was a 24.1% increase in the age-adjusted suicide rate, compared to

an increase of 6.3% among male Veterans. Similarly, when looking at race/ethnicity, we saw the largest increase in rate

among American Indian or Alaska Native Veterans. Among Veterans in VHA care, those with legal system involvement

were at increased risk of suicide-related behavior.

24

The suicide rate for recipients of VA Justice Program services was

10.2% higher in 2021 than in 2020. Additionally, in 2021, the unadjusted suicide rate among Recent Veteran VHA Users

with indications of homelessness was 38.2% higher than in 2020. Finally, 48.7% of all 6,392 Veterans who died by suicide

in 2021 had received either VHA or Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) services in 2020 or 2021,

25

while 51.3%

had received neither VHA nor VBA services. This underscores the need to continue to reach outside of VA into local

communities and neighborhoods to connect with all Veterans as part of our national approach to end Veteran suicide.

Key Findings

• In 2021, suicide was the 13th-leading cause of death for Veterans overall, and the second-leading cause of death

among Veterans under age 45-years-old.

• There were 6,392 Veteran suicide deaths in 2021. This was 114 more than in 2020.

• In 2021, there were 6,042 suicide deaths among Veteran men and 350 suicide deaths among Veteran women.

• The unadjusted rate of suicide in 2021 among U.S. Veterans was 33.9 per 100,000, up from 32.6 per 100,000 in 2020.

• In 2021, unadjusted suicide rates were highest among Veterans between ages 18- and 34-years-old, followed by

those aged 35- to 54-years-old.

• In 2021, the unadjusted suicide rate was 46.3 per 100,000 for American Indian or Alaska Native Veterans; 36.3 per

100,000 for White Veterans; 31.6 per 100,000 for Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Veterans; 17.4 per 100,000

for Black or African American Veterans; and 6.7 per 100,000 for Veterans of multiple races.

• In 2021, the unadjusted suicide rate was 19.7 per 100,000 for Veterans with Hispanic ethnicity, and it was 33.4 per

100,000 for other Veterans.

24

Palframan KM, Blue-Howells, J, Clark SC, McCarthy JF. 2020. Veterans Justice Programs: Assessing Population Risks for Suicide Deaths and

Attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 50(4):792-804.

25

Of the 6,392 Veterans who died from suicide in 2021, 38.1% received VHA services in 2020 or 2021 and 34.0% received VBA services in 2020 or 2021.

9

• Suicide was the fourth-leading cause of years of potential life lost (YPLL)

26

in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic;

in 2020 and 2021, suicide was the fifth-leading cause of YPLL.

• Among U.S. adults who died from suicide in 2021, firearms were more commonly involved among Veteran deaths

(72.2%) than among non-Veteran deaths (52.2%).

• Within the overall unadjusted suicide rate for Veterans in 2021 (33.9 per 100,000), its largest component was firearm

suicide mortality (24.5 per 100,000), followed by suffocation suicide mortality (5.0 per 100,000), poisoning suicide

mortality (2.7 per 100,000) and suicide involving other methods (1.8 per 100,000).

• Among Veterans, in each year, firearm suicide and suffocation suicide mortality rates were greater for men than for

women, while the poisoning suicide mortality rate was lower for men than for women.

• Among U.S. adult men and women, rates of firearm and of poisoning suicide mortality were greater for Veterans

than for non-Veterans, and differentials in rates by Veteran status were particularly high among women (e.g., the

firearm suicide rate among Veteran women was 281.1% higher than that of non-Veteran women, while the firearm

suicide rate among Veteran men was 62.4% higher than for non-Veteran men).

• Consistent with higher-complexity medical and psychosocial needs among Veterans who seek VHA care, rates in

2021 were higher among Recent Veteran VHA Users than for Other Veterans for all-cause mortality and for leading

causes of death, including heart disease, cancer, COVID-19, unintentional injury, and suicide.

• Age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates were higher among Recent Veteran VHA Users than for Other Veterans. In

comparison with Veterans not receiving VHA care, Veterans receiving VHA care have a higher risk with being more

likely to have lower annual incomes; poorer self-reported health status;

27

more chronic medical conditions

28

and

self-reported disability due to physical or mental health factors;

29

greater depression and anxiety;

30

and greater

reporting of trauma, lifetime psychopathology and current suicidality.

31

These differences may help to explain the

greater suicide rates among Recent Veteran VHA Users compared to Other Veterans.

• However, Recent Veteran VHA Users rates grew more slowly across 20 years when compared to rates of Veterans

without Recent VHA use. From 2001 to 2021, age-adjusted suicide rates rose 24.5% for male Veterans with Recent

VHA use and 62.6% for male Veterans without Recent VHA use. Age-adjusted suicide rates rose 87.1% for female

Veterans with recent VHA use and 93.7% for female Veterans without Recent VHA use.

• Among Recent Veteran VHA Users experiencing homelessness, the suicide rate in 2021 (112.9 per 100,000) was the

highest observed over the period 2001–2021, after increasing 38.2% since 2020.

• The suicide rate in 2021 among Recent Veteran VHA Users who received Justice Program services was also the

highest over this period (151.0 per 100,000) after a 10.2% increase since 2020.

26

Years of potential life lost is a measure of premature death which expresses the number of years that would have been lived if premature death

had not occurred. It is calculated as the difference between age at death and 75 (approximate life expectancy). If individuals live to or beyond age

75, YPLL is equal to 0. See: CDC. 1986. Premature Mortality in the United States: Public Health Issues in the Use of Years of Potential Life Lost. MMWR,

12/19/1986, 35(2S):1s-11s. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001773.htm (Accessed 7/4/2023).

27

Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. 2000. Are Patients at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers Sicker? A Comparative Analysis of Health

Status and Medical Resource Use. Arch Intern Med. 160:3252-3257.

28

Dursa EK, Barth SK, Bossarte RM, Schneiderman AI. 2016. Demographic, Military, and Health Characteristics of VA Health Care Users and Nonusers

Who Served in or During Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2009–2011. Public Health Reports. 131(6):839-843.

29

Nelson KM, Starkebaum GA, Reiber GE. 2007. Veterans Using and Uninsured Veterans Not Using Veterans Affairs (VA)

Health Care. Public Health Rep. 122:934-100.

30

Fink DS, Stohl M, Mannes ZL, Shmulewitz D, Wall M, Gutkind S, Olfson M, Gradus J, Keyhani S, Maynard C, Keyes KM, Sherman S, Martins S, Saxon

AJ, Hasin DS. 2022. Comparing Mental and Physical Health of U.S. Veterans by VA Healthcare Use: Implications for Generalizability of Research in the

VA Electronic Health Records. BMC Health Services Research. 22:1500 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08899-y

31

Meffert BN, Morabito DM, Sawicki DA, Hausman C, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH, Heinz AJ. 2019. U.S. Veterans Who Do and Do Not Utilize VA Health

Care Services: Demographic, Military, Medical, and Psychosocial Characteristics. Primary Care Companion CNS Disorders. 21(1):doi:10.4088/

PCC.18m02350.

10

• Among VHA-enrolled Recent Veteran VHA Users in 2021, the suicide rate was highest for those in Priority Eligibility

Group 5, which includes income-based eligibility (57.1 per 100,000).

• In 2020 and 2021, suicide rates were highest for Veterans who received any Community Care services, followed by

Veterans who received any VHA direct care, and suicide rates were lowest among Veterans who did not receive

either Community Care or VHA direct care.

32

• In 2020 and 2021, suicide rates were greater among Veterans who received VA Community Care services and did not

receive VHA direct care services than among Veterans who received VHA direct care services and did not receive VA

Community Care services.

• Overall, 48.7% of Veterans who died from suicide in 2021 had received VHA or VBA services in 2020 or 2021, while

51.3% of Veterans in 2021 did not.

• For the overall Veteran population in 2021, 47.2% received some VHA or VBA services in 2020 or 2021, while 52.8% of

the overall Veteran population in 2021 did not.

• In 2021, suicide rates were highest among Veterans who only received VHA services, followed by those who

received both VHA and VBA services, then those who received neither VHA nor VBA services. Suicide rates were

lowest among Veterans who received VBA services and did not receive VHA services.

• Among Recent Veteran VHA Users whose suicide deaths occurred in 2019–2021 and were reported to VHA Suicide

Prevention teams, VA Behavioral Health Autopsy Program data indicated that the most frequently identified risk

factors were: pain (55.9%), sleep problems (51.7%), increased health problems (40.7%), relationship problems (33.7%),

recent declines in physical ability (33.0%), hopelessness (30.6%) and unsecured firearms in the home (28.8%).

Need for a Whole-of-Nation Public Health Approach to Veteran Suicide Prevention:

Themes for Action

The significant and unprecedented challenges this country faced in 2021 fuel this report’s continued call to action related

to a whole-of-government and whole-of-Nation approach to suicide prevention. Suicide is a complex problem requiring

a full public health approach involving community prevention and clinical intervention. VA services are a critical part

of this public health approach, as the data from this report highlights. The data across 20 years reveals that Veterans

engaged in VHA care have shown a less sharp rise in suicide rates, underscoring the importance of VHA care. Over 20

years of Veteran suicide data also reveal a substantial reduction in suicide rates, specifically for Recent Veteran VHA Users

with mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses (77.8 per 100,000 in 2001 to 58.2 per 100,000 in 2021), falling

32.9% for Veterans with depression, 27.6% for those with posttraumatic stress disorder, 26.9% for those with anxiety and

40.4% for those with sedative use disorder. Comparing Veterans with Recent VHA use to other Veterans, we also find

notable trends. While overall rates of Veteran suicide rose across the 20 years, age-adjusted suicide rates rose 24.5% for

male Veterans with Recent VHA use compared to 62.6% for male Veterans without Recent VHA use. While less notable

for women Veterans, the age-adjusted suicide rates rose 87.1% for female Veterans with Recent VHA use and 93.7% for

female Veterans without Recent VHA use. Likewise, when looking more specifically across 2020 and 2021, we find the

greatest increase in unadjusted rates for Veterans who were neither engaged with VHA nor with VBA. From 2020 to

2021, there were also notable decreases for particular subpopulations of Veterans with Recent VHA use, including those

between ages 55- and 74-years-old (overall suicide rate -2.2%, -0.6% for men, -24.9% for women), males between ages

18- and 34-years-old (overall suicide rate -1.9%) and males aged 75-years-old and older (overall suicide rate -8.6%). These

findings underscore the importance of continuing to expand access to and engagement of Veterans in VHA and VBA

services, as over 50% of Veterans who died by suicide in 2021 had not been engaged in either service.

Yet, in order to address the complex interweaving of individual, relational, community and societal risks, VA must

continue to fully engage with other federal agencies; public-private partnerships; government at the local, state and

32

As noted above, Veterans receiving VHA care show evidence of higher risk with being more likely to have lower annual incomes, poorer self-

reported health status, more chronic medical conditions, and self-reported disability due to physical or mental health factors, greater depression

and anxiety, and greater reporting of trauma, lifetime psychopathology, and current suicidality.

11

national levels; VSOs; and local communities to reach all Veterans to support the implementation of a full public health

approach, as outlined in the White House Strategy Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide (2021)

33

and VA’s National

Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide (2018).

34

These guiding documents have been operationalized through SP 2.0;

Suicide Prevention Now initiative (SP Now); new laws, including the 2020 Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental

Health Care Improvement Act; the Veterans Comprehensive Prevention, Access to Care and Treatment Act (COMPACT)

of 2020; the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020; and emerging innovations combined with research and

program evaluation. As 2021 has again shown, this public health approach must include both community-based prevention

and clinical interventions to reduce suicide in the Veteran population. As we reflect on the core of what we learned about

Veteran suicide in 2021, 7 themes emerge for our call to action (see summary listing and description below).

While no one solution can address the complexity of all factors involved in suicide, the data clearly outlines that significant

reductions in Veteran suicide will not occur without meaningful focused effort to address Veteran firearm suicide. While

we vigorously pursue enhanced policies, research, and programs to effectively address the broader socioecological and

individual risk and protective factors which speak to “why” a Veteran may consider suicide, we must address directly the

“how” of Veteran suicide. It is inescapable that the “how” in 72% of Veteran suicide deaths is firearm compared to 52% of

non-Veteran U.S. adult suicides. We therefore begin our call to action with a focus on secure firearm storage.

1. Promote secure firearm storage for Veteran suicide prevention. Firearm ownership and storage practices vary

among Veterans.

35

One in 3 Veteran firearm owners store at least 1 firearm unlocked and loaded. This unsafe storage

practice is more frequent among Veteran firearm owners who seek VHA care (38.0%) than among other Veterans

who own firearms (31.9%).

36

As seen across years of Veteran suicide data, Veteran suicide deaths disproportionately

involve firearms; Veteran suicide rates exceed those of non-Veterans; and differentials in suicide rates by Veteran

status are greater for women than for men. Promoting secure storage of firearms has been found to reduce suicide

— this is not about taking away firearms but about promoting time and space during a time of crisis.

37

2. Implement and sustain community collaborations focused upon community-specific Veteran suicide

prevention plans. Over 60% of Veterans who died by suicide in 2021 were not seen in VHA in 2020 or 2021, and

over 50% had received neither VHA nor VBA services. In order to reach all Veterans, we must continue to expand

our work in the community through the SP 2.0 Community Based Intervention (CBI) Program. This includes the joint

VA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Governor’s Challenge to Prevent

Suicide Among Service members, Veterans, and their Families, which encompasses all 50 states, 5 territories and

work in over 1,700 local community coalitions. This also includes the SSG Fox SPGP awarding $52.5 million to 80

community-based organizations in 43 states, the District of Columbia and American Samoa in fiscal year (FY) 2023.

33

White House: Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide: Advancing a Comprehensive, Cross-Sector, Evidence-Informed Public Health Strategy. 2021.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Military-and-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Strategy.pdf

34

Department of Veterans Affairs (2018). National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide.

https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-

Veterans-Suicide.pdf

35

Combining reports from Azrael et al., 2017, and Cleveland et al., 2017, and VetPop estimates of the 2015 populations of Veteran men and women,

we estimate that in 2015 household firearm ownership among Veteran men was 62.3% higher than for non-Veteran men, and household firearm

ownership among Veteran women was 106.6% higher than for non-Veteran women.

36

Simonetti JA, Azrael D, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Miller M. 2018. Firearm Storage Practices Among American Veterans. American Journal of Preventative

Medicine. 55(4):445-454.

37

Mann JJ, Michel CA, Auerbach RP. 2021. Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. American Journal

of Psychiatry. 178(7):611-624.

12

3. Continue expansion of readily accessible crisis

intervention services. The Nation saw a reduction of

access to mental health services initially during the

COVID-19 pandemic.

38,39

Veterans desired access that was

not in-person and available whenever they needed it

40

and VHA care rapidly expanded remote care services

delivery.

41

Continued expansion of access to 24/7/365

services through the VCL 988 expansion and through

COMPACT Act implementation paved the way for more

emergency services for Veterans in acute suicidal crisis to

be provided at no cost, whether enrolled in VA or not.

42

4. Improve tailoring of prevention and intervention

services to the needs, issues, and resources unique

to Veteran subpopulations. Creating culturally

sensitive and responsive interventions to meet each

population’s needs will be required to address what 2021

revealed to us, with growing rates in American Indian/

Alaska Native Veteran populations, younger Veterans,

transitioning Service member populations, women

Veterans and more, as seen in the data for 2021.A

one-size-fits-all Veteran suicide prevention strategy will

not be effective in meeting the needs of the diverse

population of Veterans.

5. Advance suicide prevention meaningfully into

non-clinical support and intervention services,

including financial, occupational, legal, and social

domains. Suicide risk factors include issues outside

of mental health and require meaningful upstream

interventions across the Nation, as denoted in the White

House Strategy Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide

(2021).

43

Impacts related to homelessness and legal issues

were seen for Veterans in 2021, as outlined above. A

whole-of-Nation approach for upstream interventions in

employment, housing, legal support, and financial strain

is needed to address Veteran suicide prevention.

38

Zhang J, Boden M, Trafton J. 2022. Mental Health Treatment and the Role of Tele-Mental Health at the Veterans Health Administration During the

COVID-19 Pandemic.Psychological Services. 19(2):375-385.https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000530

39

Behavioral Health: Patient Access, Provider Claims Payment, and the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. GAO-21-437R. Mar 31, 2021.

40

Goetter EM, Iaccarino MA, Tanev KS, Furbish KE, Xu B, Faust KA. 2022. Telemental Health Uptake in an Outpatient Clinic for Veterans During the

COVID-19 Pandemic and Assessment of Patient and Provider Attitudes.Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 53(2):151-159.https://doi.

org/10.1037/pro0000437

41

Cornwell B, Szymanski BR, McCarthy JF. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Primary Care-Mental Health Integration Services in the VA

Health System. Psychiatric Services. 72(8):972-973.

42

The calls for action encompass work that has been ongoing since 2021 and needs for ongoing development. Thus, COMPACT and 988 are included

here, both of which had work underway in 2021.

43

White House: Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide: Advancing a Comprehensive, Cross-Sector, Evidence- informed Public Health Strategy. 2021.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Military-and-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Strategy.pdf

Call to Action: 7 Themes

Promote rearm secure storage for

Veteran suicide prevention.

Implement and sustain community

collaborations focused upon community-specic

Veteran suicide prevention plans.

Continue expansion of readily accessible

crisis intervention services.

Improve tailoring of prevention and intervention

services to the needs, issues, and resources

unique to Veteran subpopulations.

Advance suicide prevention meaningfully into

non-clinical support and intervention services,

including nancial, occupational, legal,

and social domains.

Increase access to and utilization of mental

health across a full continuum of care.

Integrate suicide prevention within medical

settings to reach all Veterans.

13

6. Increase access to and utilization of mental health services across a full continuum of care. The COVID-19

pandemic saw increased distress in the Veteran population

44

with initial decreases in utilization of mental health

services, while telemental health services expanded. During the pandemic, weekly patient encounters at VHA

decreased by 3% for ongoing suicide attempt care, while new treatment initiation for suicide attempts decreased

30%.

45

Making access as easy as possible to a continuum of evidence-based mental health treatments is an

important part of the public health approach to suicide prevention.

7. Integrate suicide prevention within medical settings to reach all Veterans. Our data again showed that a

significant percentage of VHA Veterans who died by suicide did not have a VHA mental health or substance use

disorder diagnosis. We need to creatively address the needs of those at risk who may never seek mental health

services and who may have other risk factors outside of mental health (e.g., pain, cancer, sleep disturbance) through

expansion of suicide screening, assessment, and safety planning into all medical settings, within VHA and within

community care.

Organization of Report

This year’s report is organized in alignment with the call to action, as Veteran suicide prevention will take all of us.

After an initial summary of key findings, the report is organized into two overarching sections:

1) The overall Veteran population; and

2) Veterans with Recent VHA or VBA engagement.

Specifically, the data is broken out in the following manner to assist ongoing efforts, together with you, to

reduce Veteran suicide:

• Suicide among Veterans, overall and compared to non-Veteran U.S. adults, including patterns of Veteran mortality,

including the initial 2 calendar years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

• Suicide among Veteran subpopulations, including:

• By VHA engagement, including:

- Veterans who received VHA health care

46

in the year or prior year, who in this report are described as

“Recent Veteran VHA Users.”

- Veterans who were not Recent Veteran VHA Users, who in this report are described as “Other Veterans.”

• By VBA engagement

- Overall and by receipt of categories of VBA benefits.

After each of these sections, the report will reflect on relevant research that has served to inform next steps, where VA

is moving next steps forward, and specific actions that VA and each of us across the Nation can take to join together in

Veteran suicide prevention. The detailed analyses of suicide mortality over time and across Veteran subgroups can help

us together to advance suicide prevention initiatives across both the individual and societal levels.

44

Fischer IC, Na PJ, Harpaz-Rotem I, Krystal JH, Pietrzak RH. 2023. Characterization of Mental Health in US Veterans Before, During, and 2 Years After

the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 6(2):e230463.

45

Zhang J, Boden M, Trafton J. 2022. Mental Health Treatment and the Role of Tele-Mental Health at the Veterans Health Administration During the

COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychological Services. 19(2):375-385.

46

VHA health care receipt is here defined as having at least 1 VHA inpatient or outpatient utilization record.

14

Part 1: Suicide Among Veterans, 2001–2021

Suicide Deaths

• In 2021, there were 46,412 suicides among U.S. adults. These included 6,392 suicides among Veterans

47

(114 more

than in 2020) and 40,020 among non-Veterans (2,000 more than in 2020).

• Among Veterans, non-Veteran adults, and U.S. adults overall, the number and rate of suicide deaths increased from

2020 to 2021 (Figure 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 1: Suicide Deaths Among Veterans and Non-Veteran U.S. Adults, by Year, 2001–2021

47

For this report, Veterans were defined as persons who had been activated for federal military service and were not currently serving at the time of

death. For more information see the accompanying 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report Methods Summary.

Veterans Non-Veteran Adults

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

45,000

40,000

35,000

30,000

25,000

20,000

15,000

10,000

5,000

0

2020 2021

6,000

6,392

23,580

40,020

Number of Suicides

15

Figure 2 details variation in the number of Veteran suicides, by year from 2001 to 2021.

Figure 2: Veteran Suicide Deaths, 2001–2021

Average Number of Suicides Per Day

48

• In 2021, there were on average 127.2 suicides per day among U.S. adults, including 17.5 per day among Veterans and

109.6 per day among non-Veteran adults.

• Among all U.S. adults, including Veterans, the average number of suicides per day rose from 81.0 per day in 2001 to

127.2 in 2021. The average number per day among U.S. adults was highest in 2018 (127.4 per day).

• The average number of Veteran suicides per day rose from 16.4 in 2001 to 17.5 in 2021. For U.S. adults, the average

number of suicides per day was highest in 2018 for Veterans (18.4 per day). Of the on-average 17.5 Veteran suicides

per day in 2021, approximately 38.1% (6.7 per day) were among Recent Veteran VHA Users

49

and 61.9% (10.8 per day)

were among Other Veterans.

48

Decreases in the size of the Veteran population and increases in the size of the U.S. population over this period limit interpretation of these

statistics. Rates of suicide, stratified by group, are the appropriate for understanding changes in Veteran and non-Veteran populations. These are

included elsewhere in this report and in the accompanying data appendix.

49

Consistent with prior reports, Recent Veteran VHA Users were defined as Veterans who received inpatient or outpatient care health care (in person

or via telehealth) at a VHA facility in the year of interest or the prior year (here, 2021 or 2020). Health care received from non-VHA facilities, including

such care that was funded by VA (i.e., community care) was not included.

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

7,000

6,800

6,600

6,400

6,200

6,000

5,800

5,600

2020 2021

6,000

6,142

6,008 6,004

6,035

6,126

6,249

6,567 6,545

6,519

6,447

6,441

6,501

6,645

6,467

6,481

6,616

6,686

6,392

6,278

6,718

Number of Suicides

16

Suicide Rates

From 2001 to 2021, the Veteran population decreased by 27.0%, from 25.8 million to 18.8 million. During this same

timeframe, the non-Veteran U.S. adult population increased by 28.4%, from 186.5 million to 239.5 million. In this context, it is

important to assess suicide mortality rates, which convey the incidence of suicide relative to the size of the population.

Unadjusted suicide rates represent the number of suicide deaths relative to the population’s time at risk of being

observed with a suicide death.

50

Rates are reported as suicides per 100,000.

51

Direct adjusted rates are used for

comparisons while adjusting for population differences, such as age and sex distributions.

52

To describe the burden of

suicide in a given population and period, we use unadjusted rates. To compare rates across populations or periods, we

use direct adjusted rates.

53

• The unadjusted suicide rate for Veterans was 23.3 per 100,000 in 2001 and 33.9 per 100,000 in 2021. For non-Veteran

U.S. adults, the suicide rate was 12.6 per 100,000 in 2001 and 16.7 per 100,000 in 2021.

• In 2021, Veterans between ages 18- and 34-years old had an unadjusted suicide rate of 49.6 per 100,000, while the

rate was 35.5 per 100,000 for those between ages 35- and 54-years old; 29.9 per 100,000 for those between ages 55-

and 74-years old; and 32.1 per 100,000 for those aged 75-years-old and older.

• In 2021, the unadjusted suicide rate of Veteran men was 35.9 per 100,000 (3.5% higher than in 2020) and it was 17.5

per 100,000 for Veteran women (23.7% higher than in 2020).

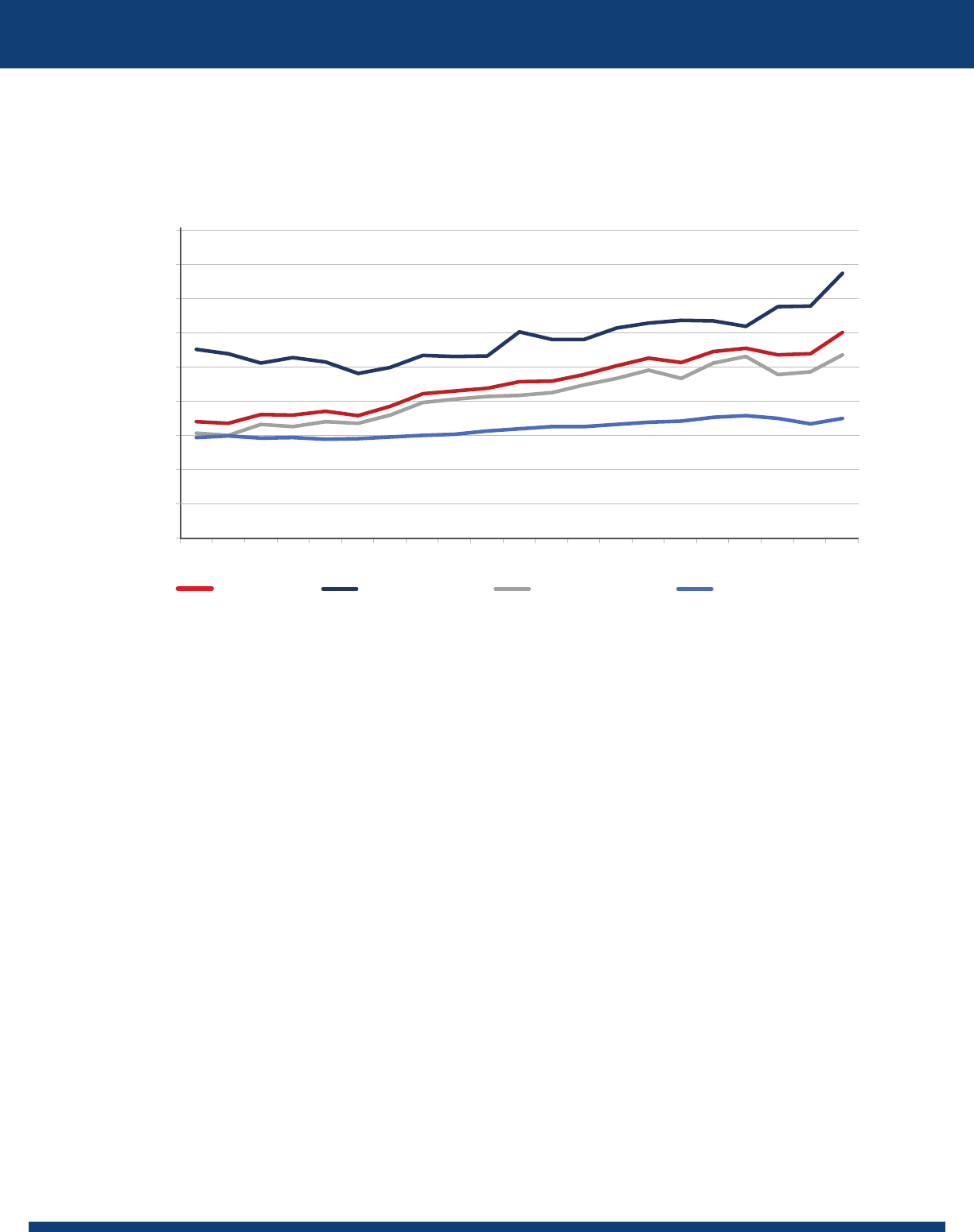

• Age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates from 2001 to 2021 are presented in Figure 3 for Veterans and non-Veteran U.S.

adults, by year. The difference in age- and sex-adjusted rates was greatest in 2021, when the age- and sex-adjusted

rate for Veterans was 71.8% greater than that of non-Veteran adults.

• Bivariate comparisons indicated that Veteran age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates were significantly greater in 2021

than in 2019 or 2020.

50

Risk time is measured using mid-year population estimates when individuals’ exact risk times were unavailable. It was calculated exactly for

analyses of subgroups of Veterans with recent VHA care.

51

For the Veteran population, risk time was assessed using the mid-year population estimate, as detailed in the accompanying methods summary.

When risk time was assessed per individual level risk-time information, we included “per 100,000 person-years.”

52

Unadjusted rates communicate the magnitude of suicide mortality in a given population in a time period. Suicide risks differ across age and sex

categories. Consequently, if groups differ in these characteristics, then that variation may account for some of the differences in unadjusted rates.

Adjusted rates translate the unadjusted rate for a population into a measure of what the rate would be if the compared populations had the same

distributions of the demographic factors that are adjusted for. Per standard practice, adjusted rates are calibrated to the demographic distribution

of the U.S. adult population in 2000. Calculating adjusted rates (e.g., age-adjusted or age- and sex-adjusted rates) enhances rate comparisons by

adjusting for population demographic differences. Notably, the Veteran and non-Veteran adult populations differ by age and sex, with Veterans

being on average older and more male.

53

The interpretation of adjusted rates is somewhat technical. They represent the level of suicide mortality that we would see in the population and

time period if the population had the same demographic distribution of a standard population, at least in terms of the adjustment variable(s).

Consistent with current practice, in this report adjusted rates use the U.S. adult population in 2000 as the standard population. Unadjusted rates

are presented when adjustment was not possible due to small numbers within strata. Use of the direct method and the standard U.S. population of

2000 for adjustment are consistent with CDC reporting (Garnet MF, Curtin SC. 2023. Suicide Mortality in the United States, 2001–2021. CDC NCHS,

Data Brief 464. Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age Adjustment Using the 2000 Projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2000 Statistical Notes, no. 20.

Hyattsville, Maryland: NCHS. January 2001).

17

Figure 3: Age- and Sex-Adjusted Suicide Rate, Veterans and Non-Veteran U.S. Adults, 2001–2021

Suicide Rates, by Sex

• Figure 4 presents age-adjusted suicide rates for Veteran men and for Veteran women, by year, 2001–2021. For

Veteran men and Veteran women, rates were highest in 2021.

• From 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 6.3% among Veteran men and 24.1% among Veteran

women. From 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 4.9% among non-Veteran men and 2.6% among

non-Veteran women.

• In 2021, the age-adjusted suicide rate of Veteran men was 43.4% greater than that of non-Veteran U.S. adult

men, and the age-adjusted suicide rate of Veteran women was 166.1% higher than that of non-Veteran U.S.

adult women.

54

54

For men and for women, differentials in adjusted rates by Veteran status were highest in 2021.

Veterans Non-Veteran Adults

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Age- and Sex-Adjusted Rate per 100,000

18

Figure 4: Age-Adjusted Suicide Rate, Male and Female Veterans, 2001–2021

Suicide Rates, by Age

Figure 5 presents unadjusted suicide rates for Veterans, by age categories and year, 2001–2021.

From 2020 to 2021, the suicide rate among Veterans aged 18- to 34-years-old increased by 7.1%; the rate for Veterans

aged 35- to 54-years-old rose by 10.7%; the rate for Veterans aged 55- to 74-years old rose by 7.4%; and for Veterans aged

75-years-old and older, the suicide rate fell by 8.0%.

Figure 5: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, Veterans, by Age Group, 2001–2021

Male Veterans Female Veterans

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Age-Adjusted Rate per 100,000

18-34 35-54 55-74 75+

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

19

Suicide Rates, by Sex and Age

Figures 6 and 7 present suicide rates

55

for Veteran men and women, by age categories and year, 2001–2021.

• In 2021, suicide rates were highest among Veterans between ages 18- and 34-years-old (55.4 per 100,000 among

Veteran men aged 18- to 34-years-old, and 24.8 per 100,000 among Veteran women aged 18- to 34-years-old).

• Suicide rates among male Veterans aged 75-years-old and older decreased by 8.1% from 2020 to 2021, while rates

for all other groups increased.

Figure 6: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, Male Veterans, by Age Group, 2001–2021

Figure 7: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, Female Veterans, by Age Group,

56

2001–2021

55

As rates are specific to age- and sex-subgroups, adjustment was not applicable.

56

Due to the small number of deaths among older age groups of female Veterans, the 55- to 74-years-old and 75-years-old and older age groups are

combined, for reporting purposes.

18-34 35-54 55-74 75+

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

18-34 35-54 55+

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

20

Suicide Rates, by Race and Ethnicity

Figure 8 presents unadjusted Veteran suicide rates, by race.

57

• In 2021, the suicide rate was 36.3 per 100,000 for White Veterans; 31.6 per 100,000 for Asian, Native Hawaiian or

Pacific Islander Veterans; 46.3 per 100,000 for American Indian or Alaska Native Veterans; 17.4 per 100,000 for Black

or African American Veterans; and 6.7 per 100,000 for Veterans of multiple races.

• In 2021, the highest suicide rate was among American Indian or Alaska Native Veterans and the lowest rate was

among Veterans of multiple races.

• Among the U.S. adult general population in 2021, which includes Veteran and non-Veteran adults and uses more

detailed race categories, unadjusted suicide rates were also highest among those who were American Indian or

Alaska Native, followed by those who were White, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiple races, Black or

African American and Asian.

58

Figure 8: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, Veterans, by Race,

59

2001–2021

57

It was not possible to generate adjusted rates, due to data constraints. Consequently, differences in rates may in part be due to population

differences in demographic factors that are independently associated with suicide risk.

58

Note that the U.S. adult population includes both Veteran and non-Veteran U.S. adults. Suicide rates for adults in the U.S. general population are

derived from CDC WONDER. For more information on CDC WONDER, see: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html. Unadjusted suicide

rates among U.S. adults in 2021 were as follows: American Indian or Alaska Native: 21.7 per 100,000; White: 20.1 per 100,000; Native Hawaiian or

other Pacific Islander: 14.0 per 100,000; multiple races: 12.0 per 100,000; Black or African American: 10.6 per 100,000; and Asian: 8.3 per 100,000.

59

Categories presented are mutually exclusive. The availability of information regarding race demographics for the overall Veteran population

is limited, sometimes combining the Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander race categories. To provide the most complete information

available, we present information using this combined category. The percentage of Veteran suicide deaths missing race information was 7.8% in

2001, 7.7% in 2002, 7.7% in 2003, 8.0% in 2004, 7.5% in 2005, 6.9% in 2006, 7.4% in 2007, 11.0% in 2008, 13.7% in 2009, 2.9% in 2010, 2.3% in 2011,

2.5% in 2012, 2.6% in 2013, 3.0% in 2014, 2.7% in 2015, 2.9% in 2016, 2.5% in 2017, 2.8% in 2018, 3.4% in 2019, 4.7% in 2020 and 4.2% in 2021.

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

White

Black or African

American

American Indian

or Alaska Native

Asian, Native Hawaiian,

or Pacific Islander

Multiple Race

21

Figure 9 presents unadjusted suicide rates for Veterans, by Hispanic ethnicity.

60

• From 2020 to 2021, suicide rates increased 0.5% for Hispanic Veterans and 4.7% for non-Hispanic Veterans. By

comparison, in the U.S. adult general population, suicide rates increased by 6.1% among individuals with Hispanic

ethnicity and by 3.7% among other adults.

Figure 9: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, Veterans, by Hispanic Ethnicity, 2001–2021

60

It was not possible to generate adjusted rates, due to data constraints. Consequently, differences in rates may in part be due to population

differences in demographic factors that are independently associated with suicide risk.

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

Hispanic Non-Hispanic

13.3

19.7

20.4

33.4

22

Suicide Rates in Year Following Military Separation

Figure 10 presents the unadjusted suicide rate per 100,000 over 12 months following Veterans’ separation from active

military service, by year of separation, 2010–2020.

61,62

Suicide rates in the 12 months following separations ranged from 34.8 per 100,000, for Veterans who separated in 2010,

to 48.9 per 100,000, for Veterans who separated in 2019.

Figure 10: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, 12 Months Following Separation from Active Military Service, by Year

of Separation, 2010–2020

61

Twelve-month suicide mortality rates are reported for cohorts of Veterans who separated from military service in the years 2010 through 2020.

Separations were identified using VA/Department of Defense Identity Repository (VADIR) data. Reporting is not included for years prior to 2010

due to data constraints. Given small cell sizes, it was not possible to calculate adjusted rates. The 12-month observation period for the most recent

cohort (separations in calendar year 2020) extended into 2021, using the most current available mortality data. Review of 95% confidence intervals

(not shown) indicated that these were overlapping for each year, indicating no statistical differences in rates over this period.

62

In 2010, there were 226,928 Veterans with most recent separations from active military service, and there were 195,385 in 2020. For Veterans who

separated in 2010, 16.8% were female and the median age at separation was 26. For those who separated in 2020, 17.4% were female and the

median age at separation was 27. There were 79 and 93 Veteran suicides within 12 months of military separations in 2010 and 2020, respectively.

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2020

Rate per 100,000 Person-Years

Year of Separation

34.8

42.8

39.4

42.1

41.7

35.6

35.8

46.7

48.1

48.9

47.6

23

Figure 11 presents unadjusted suicide rates in the 12 months following separation, by year of separation and service branch.

For the most recent separation cohort, who separated from active military service in 2020, suicide rates over the

following 12 months were highest among those who separated from the Marines Corps (80.9 per 100,000), followed by

the Navy (50.1 per 100,000) and Army (46.1 per 100,000).

63

Figure 11: Unadjusted Suicide Rate, 12 Months Following Separation from Active Military Service, by

Branch of Service and Year of Separation, 2010–2020

64

63

Not presented for Veterans who separated from the Air Force in 2020, as there were fewer than 10 suicide deaths.

64

Rates are suppressed if there were fewer than 10 suicide deaths, with dotted lines connecting non-suppressed data points. The dotted lines

represent suppressed rates and should not be interpreted as estimated rates.

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2020

Rate per 100,000

Year of Separation

Army Air Force Navy Marines

24

Method-Specific Suicide Rates

Figure 12 presents method-specific

65

suicide rates among Veterans, by year, 2001–2021, and the percentage change in

rates from 2001 to 2021.

• In each year, Veteran firearm suicide rates exceeded those of all other categories.

• Changes in Veteran method-specific suicide rates are listed below:

2001 to 2021 2019 to 2020 2020 to 2021

Firearm suicide rate +58.3% +1.4% +5.5%

Poisoning suicide rate (-13.4%) +0.4% (-1.1%)

Suocation suicide rate +55.6% (-10.8%) +5.0%

Other methods suicide rate +18.2% +6.3% (-5.9%)

Figure 12: Unadjusted Method-Specific Suicide Rate, Veterans, 2001–2021, and Change from 2001 to 2021

Similar to patterns for Veterans, among non-Veteran U.S. adults firearm suicide mortality rates exceeded all other

method-specific suicide rates in each year.

66

For non-Veteran U.S. adults, there was also a decrease from 2001 to 2021 in

poisoning suicide mortality rates (-11.2%) and increases in rates of firearm suicide mortality (+30.9%), suffocation suicide

mortality (+70.7%) and suicide involving other methods (+39.8%).

67

65

Methods were assessed from death certificate data per ICD-10 codes X72-X74 for firearm, X60-X69 for poisoning (including intentional overdose)

and X70 for suffocation (including strangulation). “Other Means” (U03, X71, X75-X84, Y87.0) included cutting/ piercing, drowning, falls, fire/flame,

other land transport, being struck by/against and other specified or unspecified injury.

66

Results not shown.

67

Firearm suicide mortality accounted for a larger portion of the overall Veteran suicide rate in 2001 and 2021 (66.5% and 72.2%, respectively) than

for non-Veterans (52.7% and 52.2%, respectively).

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

+58.3

-13.4

+55.6

+18.2

Percentage Change,

2001 to 2021

Firearm Poisoning Suffocation Other

25

Figures 13 and 14 show method-specific suicide rates for male Veterans and female Veterans, respectively.

Figure 13: Unadjusted Method-Specific Suicide Rate, Male Veterans, 2001–2021, and Change from 2001 to 2021

Figure 14: Unadjusted Method-Specific Suicide Rate, Female Veterans, 2001–2021, and Change from 2001

to 2021

68

68

Rates are suppressed for female Veterans, Other Means, for 2002 and 2013. Dashed lines are for presentation purposes and do not represent

estimated rates.

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

+61.8

-17.6

+54.0

+21.7

Percentage Change,

2001 to 2021

Firearm Poisoning Suffocation Other

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

2020 2021

Rate per 100,000

+157.7

+249.5

+2.2

-8.6

Percentage Change,

2001 to 2021

Firearm Poisoning Suffocation Other

26

Method-Specific Suicide Rates, by Veteran Status and Sex

Here we compare method-specific rates of Veteran men and women, and we compare rates of non-Veteran men and

women.

69

As indicated below, method-specific suicide rates varied by sex for Veterans and non-Veterans. The magnitude

of this variation differed by Veteran status.

• Among Veterans, in each year, firearm suicide and suffocation suicide mortality rates were higher for men than for

women, while poisoning suicide mortality rates were lower for men than for women. In 2021:

• Firearm suicide rate: 190.1% higher for Veteran men than for Veteran women

• Suffocation suicide rate: 50.9% higher for Veteran men than for Veteran women

• Poisoning suicide rate: 40.4% lower for Veteran men than for Veteran women

• Among non-Veteran U.S. adults, in each year, all method-specific suicide rates were greater for men than for

women. In 2021:

• Firearm suicide rate: 580.7% higher for non-Veteran men than for non-Veteran women

• Suffocation suicide rate: 313.0% higher for non-Veteran men than for non-Veteran women

• Poisoning suicide rate: 9.6% higher for non-Veteran men than for non-Veteran women

• Poisoning suicide mortality rates were lower for Veteran men than for Veteran women, and they were higher for

non-Veteran men than for non-Veteran women.

Method-Specific Suicide Rates, by Sex and Veteran status

Here we compare method-specific rates of male Veterans to those of male non-Veterans, and we compare method-

specific rates of female Veterans to those of female non-Veterans.

70,71

As indicated below, method-specific suicide rates

varied by Veteran status, for both men and women. The magnitude of this variation differed by sex.

• Among men, in each year, 2001–2021, firearm suicide mortality and poisoning suicide mortality rates were higher,

and suffocation mortality rates were lower, for Veteran men than for non-Veteran men. In 2021:

• Firearm suicide rate: 62.4% higher for Veteran men than for non-Veteran men

• Poisoning suicide rate: 14.3% higher for Veteran men than for non-Veteran men

• Suffocation suicide rate: 31.3% lower for Veteran men than for non-Veteran men

• Among women, in each year, 2001–2021, firearm suicide mortality and poisoning suicide mortality rates were higher

for Veteran women than for non-Veteran women. In 2021:

• Firearm suicide rate: 281.1% higher for Veteran women than for non-Veteran women

• Poisoning suicide rate: 110.1% higher for Veteran women than for non-Veteran women

• Among women, the suffocation suicide rate in 2021 was 88.0% higher for Veteran women than for non-

Veteran women.

72

69

Due to small cell sizes, it was not possible to provide age-adjusted method-specific rates.

70

Due to small cell sizes, it was not possible to provide age-adjusted method-specific rates.

71

Compared to non-Veteran adults, Veterans are more likely to own firearms. Estimates derived from 2015 National Firearm Survey reports and

VetPop data suggest that in 2015 firearm ownership was approximately 62% higher for Veteran men than for non-Veteran men, and it was

approximately 107% higher for Veteran women than for non-Veteran women.

72

This direction and scale of this differential ranged from 2006, when Veteran women had a 13.7% lower rate of suffocation suicide than non-Veteran

women, to 2021, when Veteran women had an 88.0% higher suffocation suicide rate than non-Veteran women.

27

Lethal Means Involved in Suicide Deaths

Table 1 provides information on lethal means, or methods, involved in suicide deaths of Veterans and non-Veteran U.S.

adults in 2021 and a measure of change compared to suicides in 2001.

• Overall and by sex, suicide deaths among Veterans were more likely to involve firearms than suicide deaths among

non-Veteran U.S. adults. For example, firearms were involved in 73.4% of suicide deaths in 2021 among Veteran

men, compared to 57.2% of suicide deaths among non-Veteran men; and firearms were involved in 51.7% of suicides

by Veteran women in 2021, compared to 34.6% of non-Veteran women.

• Among Veteran suicide deaths in 2021, relative to those in 2001, there were increases in the percentage involving

firearms (+5.7%) and suffocation (+0.9%) and decreases for poisoning (-5.4%) and other means (-1.2%).

• For suicide deaths of non-Veteran U.S. adults, there were increases from 2001 to 2021 in the percentage involving

suffocation (+6.1%) and other means (+0.5%) and decreases in the percentage involving firearms (-0.5%) and

poisoning (-6.0%).

72%

Firearm

Suicide

5.7%

1 in 3

of Veteran suicides

were by firearm in 2021.

Veteran firearm suicides

from 2001 to 2021

increased by

Firearm suicide rate among

Veteran men was

62.4% higher

than for non-Veteran

men in 2021.

Firearm suicide rate among

Veteran women was

281.1%

higher

than non-Veteran

women in 2021. There was a

14.7% increase in Veteran

women firearm suicide deaths

from 2001

–

2021.

Firearm ownership is

more prevalent

among Veterans (45%)

than non-Veterans (19%).

Veteran firearm owners store

at least one firearm

unlocked and loaded.

.

28

Table 1: Suicide Deaths, Methods Involved, 2021 and Difference From 2001, by Veteran Status, Sex and

Age Groups

73

Veterans

Non-Veteran

U.S. Adults

Veteran

Men

Non-Veteran

Men

Veteran

Women

Non-Veteran

Women

2021 Change 2021 Change 2021 Change 2021 Change 2021 Change 2021 Change

All Ages

Firearms 72.2% +5.7% 52.2% -0.5% 73.4% +6.1% 57.2% -0.8% 51.7% +14.7% 34.6% -0.9%

Poisoning 7.8% -5.4% 12.4% -6.0% 6.9% -5.5% 7.7% -4.7% 23.7% -19.2% 28.8% -9.2%

Suocation 14.9% +0.9% 26.8% +6.1% 14.6% +0.5% 26.9% +4.5% 19.7% +9.3% 26.8% +11.1%

Other 5.2% -1.2% 8.6% +0.5% 5.2% -1.1% 8.3% +1.0% 4.9% -4.9% 9.8% -1.0%

Ages 18–34

Firearms 66.2% +5.3% 49.7% -1.9% 68.0% +5.9% 53.9% -0.8% 49.4% +12.7% 31.9% -3.9%

Poisoning 5.9% -5.4% 8.9% -3.8% 4.6% -5.5% 6.2% -3.1% 18.8% -17.9% 20.9% -9.5%

Suocation 22.7% +0.6% 32.5% +4.0% 22.0% -0.5% 31.4% +2.2% 29.4% -- 36.8% +12.7%

Other 5.2% -0.5% 8.9% +1.6% 5.4% +0.2% 8.6% +1.7% -- -- 10.4% +0.7%

Ages 35–54

Firearms 62.1% +7.7% 46.5% -0.1% 63.3% +8.2% 50.1% -1.8% 49.7% +10.4% 34.9% +2.3%

Poisoning 9.0% -10.0% 13.4% -11.4% 7.7% -10.2% 8.7% -8.8% 23.5% -22.3% 28.5% -15.6%

Suocation 23.2% +3.8% 31.5% +11.6% 23.3% +3.5% 32.6% +10.1% 21.5% -- 28.0% +14.9%

Other 5.7% -1.4% 8.6% -0.1% 5.7% -1.4% 8.6% +0.5% -- -- 8.7% -1.5%

Ages 55–74

Firearms 72.7% -3.2% 56.8% -6.2% 73.5% -2.8% 63.8% -7.4% 55.3% -- 36.5% -5.4%

Poisoning 8.9% -1.1% 15.6% -1.1% 7.9% -1.8% 9.0% -0.5% 30.1% -- 34.9% -0.5%

Suocation 12.4% +4.0% 18.6% +6.6% 12.6% +4.2% 18.7% +6.4% -- -- 18.3% +6.8%

Other 6.0% +0.3% 9.0% +0.8% 6.0% +0.4% 8.5% +1.5% -- -- 10.3% -0.9%

Ages 75+

Firearms 86.5% +5.1% 73.5% +4.8% 86.6% +4.9% 81.8% +3.3% -- -- 36.4% +0.4%

Poisoning 6.1% -0.3% 11.8% +1.6% 6.1% -0.4% 6.0% +0.7% -- -- 38.4% +11.1%

Suocation 4.0% -2.0% 9.1% -4.0% 4.1% -1.8% 7.8% -3.2% -- -- 14.9% -5.6%

Other 3.3% -2.8% 5.6% -2.3% 3.3% -2.7% 4.5% -0.9% -- -- 10.3% -5.9%

73

“Change” is the absolute difference comparing the percentage of suicide deaths in 2021 to the percentage of suicide deaths in 2001. Percentages

and differences are not presented when based on fewer than 10 deaths, indicated by “--”.

29

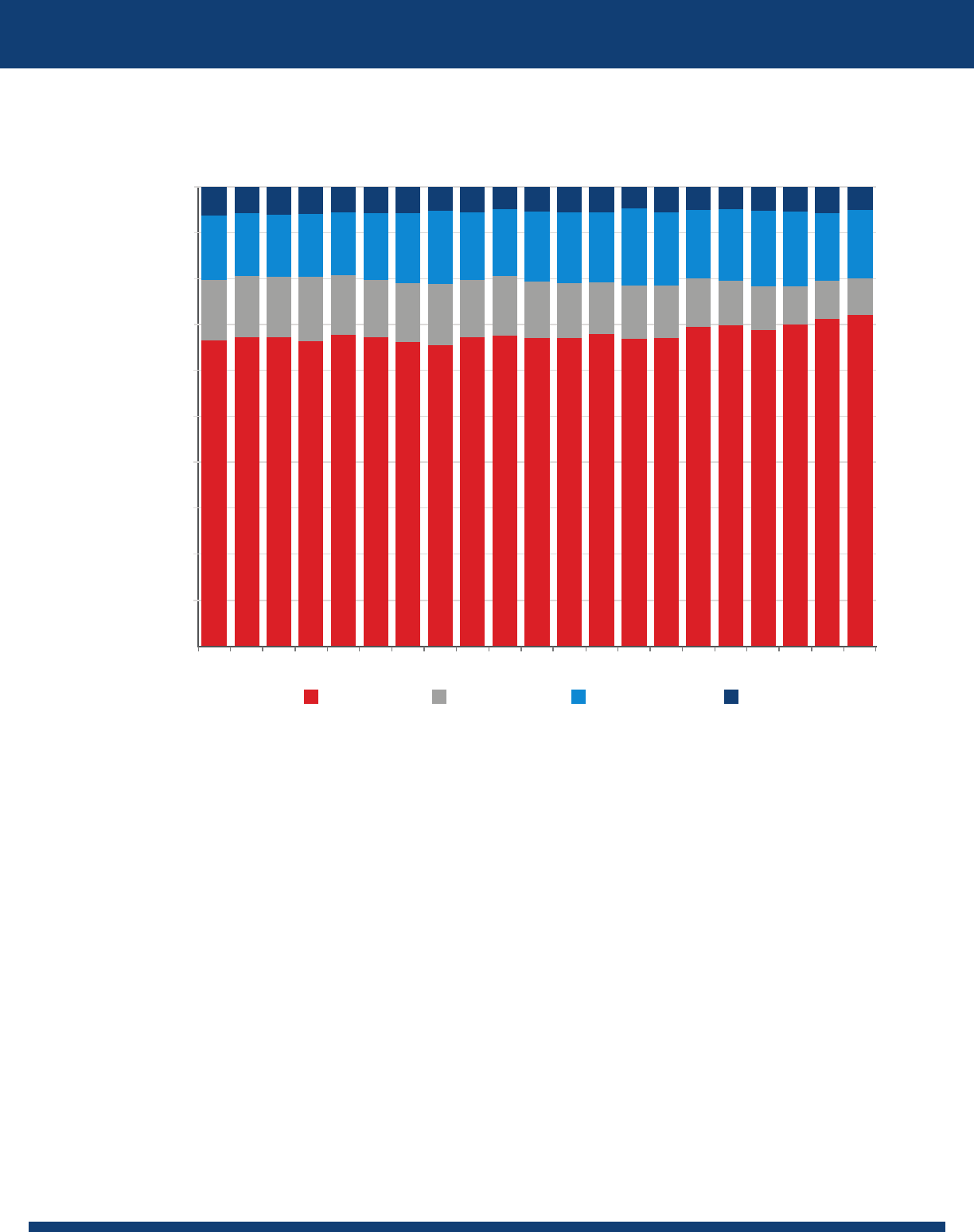

Figure 15 presents the distribution of methods involved in Veteran suicide deaths, from 2001–2021.

Figure 15: Methods Involved, Percentage, Veteran Suicide Deaths, 2001–2021

• From 2020 to 2021, among Veteran suicide deaths, the involvement of firearms and suffocation increased from

71.3% to 72.2% and 14.8% to 14.9%, respectively, while the involvement of poisoning and other methods decreased,

from 8.3% to 7.8% and from 5.7% to 5.2%, respectively.

• In 2021, firearms were involved in 73.4% of suicides by male Veterans, up from 72.3% in 2020, and in 51.7% of

suicides by female Veterans, up from 48.6% in 2020.

• The distribution of methods involved in suicides by non-Veteran U.S. adults changed from 2020 to 2021.

Involvement of firearms increased from 50.2% to 52.2%, while poisoning and suffocation decreased, from 12.9% to

12.4% and from 28.5% to 26.8%, respectively.

• Considering trends from 2019, prior to the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, from 2019 to 2021, among Veteran

suicide deaths, the involvement of firearms increased from 70.0% to 72.2%, while the involvement of poisoning,

suffocation and other methods decreased, from 8.2% to 7.8%, 16.5% to 14.9% and 5.4% to 5.2%, respectively. Among

non-Veteran U.S. adults from 2019 to 2021, involvement of firearms increased from 47.6% to 52.2%, while poisoning,

suffocation, and other methods decreased, from 13.9% to 12.4%, 29.7% to 26.8% and 8.7% to 8.6%, respectively.

Firearm Poisoning Suffocation Other

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Percent

6.4

5.9

5.2

5.7

5.4

5.2

5.0

5.2

5.6

4.8

5.55.6

5.4

5.0

5.6

5.3

5.75.8

5.5

5.9

6.2

13.9

13.6

14.9

14.8

16.5

16.6

15.5

14.8

16.0

16.7

15.4

15.4

15.4

14.5

14.7

15.9

15.2

14.5

13.7

13.8

13.5

13.2

13.3

7.8

8.3

8.2

9.3

9.7

10.5

11.4

11.6

11.1

11.9

12.2

13.0

12.6

13.4

12.9

12.4

13.1

14.0

13.1

66.5

67.3

72.2

71.3

70.0

68.9

69.9

69.6

67.1

66.9

68.0

67.267.1

67.5

67.2

65.4

66.1

67.2

67.7

66.3

67.3

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

30

Comparing Suicide Mortality Among Veterans and Non-Veteran U.S. Adults

Efforts to understand Veteran suicide include comparisons of suicide statistics for Veterans and non-Veteran U.S. adults.

Here, we consider suicide measures as resources for comparisons, and we discuss findings.

• Counts of suicide deaths. In 2021, there were 6,392 suicides among Veterans and 40,020 among non-Veteran