©2014 International Monetary Fund

IMF Country Report No. 14/80

MALAYSIA

2013 ARTICLE IV CONSULTATION—STAFF REPORT;

PRESS RELEASE; AND STATEMENT BY THE EXECUTIVE

DIRECTOR FOR MALAYSIA

Under Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, the IMF holds bilateral discussions with

members, usually every year. In the context of the 2013 Article IV consultation with Malaysia,

the following documents have been released and are included in this package:

The Staff Report prepared by a staff team of the IMF for the Executive Board’s

consideration on March 7, 2014, following discussions that ended on December 16, 2013,

with the officials of Malaysia on economic developments and policies. Based on

information available at the time of these discussions, the staff report was completed on

February 14, 2014.

An Informational Annex prepared by the IMF.

A Press Release summarizing the views of the Executive Board as expressed during its

March 7, 2014 consideration of the staff report that concluded the Article IV consultation

with Malaysia.

A Statement by the Executive Director for Malaysia.

The following document will be separately released.

Selected Issues Paper

The publication policy for staff reports and other documents allows for the deletion of market-

sensitive information.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund Publication Services

PO Box 92780 Washington, D.C. 20090

Telephone: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: [email protected]

Web: http://www.imf.org

Price: $18.00 per printed copy

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

March 2014

MALAYSIA

STAFF REPORT FOR THE 2013 ARTICLE IV CONSULTATION

KEY ISSUES

Near-term outlook. Malaysia’s healthy, noninflationary growth continued in 2013, albeit

at a somewhat slower clip than earlier years. While domestic demand remained robust,

the economy was buffeted by external headwinds, including from volatile capital flows in

spring-summer and weak export growth. The current account surplus continued to

narrow, although it remains comfortably in surplus. Continued strength in domestic

demand, especially investment, and a pickup in external demand should help maintain

robust growth going forward despite the welcome fiscal tightening.

Macroeconomic policy mix. Staff welcomes the timely, credible, and gradual

recalibration of macroeconomic policies, which should help achieve a smooth transition

to the post-UMP environment. The budget is being tightened and fiscal institutions

strengthened. Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), which maintains an accommodative

monetary stance for now, possesses ample policy credibility and should be able to

contain any second round price effects associated with fuel subsidy reductions.

Fiscal policy breakthrough. Amidst concerns about Malaysia’s public finances and a

sharp narrowing of the external surplus in spring-summer, the authorities took timely

action to secure fiscal sustainability and assure markets. Staff welcomes the

comprehensive and gradual approach to fiscal adjustment, which includes subsidy

rationalization, broadening of revenue bases, and the strengthening of the social safety

net. It urges the authorities to persevere in their efforts to rebuild fiscal buffers, improve

the management of contingent liabilities, and address ageing-related fiscal challenges.

Financial stability. Malaysia’s financial system is sound, supported by strong supervision

and regulation. Targeted, yet escalating macroprudential policies (MAPs) are being

employed to deal with the risks from high rates of credit growth and rising household

debt. These risks, as well as the effectiveness of MAPs, should continue to be closely

monitored. The exchange rate remains flexible and, together with Malaysia’s ample

financial buffers and sound monetary and fiscal policies; should safeguard the economy

from potentially volatile capital flows.

Inclusive growth: the role of human capital. The authorities have designed and are

implementing several ambitious transformation programs and blueprints to turn

Malaysia into a high-income, knowledge and innovation based nation by 2020. Their

efforts are on track, although skills mismatches need to be addressed through intensified

human capital development efforts. Progress in education, as outlined in the Malaysia

Education Blueprint, 2013−2025, is a high priority. This will call for achieving stronger

performance in education in a tighter budgetary environment.

February 14, 2014

MALAYSIA

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Approved By

Hoe Ee Khor and

Ranil Salgado

Mission dates: December 5−16, 2013

The mission comprised Alexandros Mourmouras (Head), Niamh

Sheridan, Elif Arbatli, Jade Vichyanond (all APD), Mustafa Saiyid

(MCM), and Geoffrey Heenan (Singapore Resident Representative) and

Seen Meng Chew (Resident Representative’s Office). Hoe Ee Khor

(APD Reviewer) participated in the policy discussions.

CONTENTS

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS, OUTLOOK, AND RISKS ______________________________________________ 4

NEAR-TERM ECONOMIC POLICIES: ACHIEVING A SMOOTH TRANSITION ___________________ 7

FISCAL POLICY: BREAKTHROUGH _____________________________________________________________ 10

FINANCIAL STABILITY __________________________________________________________________________ 14

CAPITAL OUTFLOWS: VULNERABILITIES AND RESILIENCE __________________________________ 20

EXTERNAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS __________________________________________________________ 22

BOOSTING GROWTH AND INCLUSION: THE ROLE OF HUMAN CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT _ 23

STAFF APPRAISAL ______________________________________________________________________________ 24

BOXES

1. Fiscal Policy Committee ______________________________________________________________________ 27

2. Goods and Services Tax (GST) _______________________________________________________________ 28

3. Medium-Term Fiscal Consolidation __________________________________________________________ 29

4. Household Debt _____________________________________________________________________________ 31

FIGURES

1. Growth and Exports __________________________________________________________________________ 32

2. Inflation and Domestic Resource Constraints ________________________________________________ 33

3. Monetary Developments _____________________________________________________________________ 34

4. Fiscal Policy Developments __________________________________________________________________ 35

5. Capital Inflows _______________________________________________________________________________ 36

6. Financial Sector Developments ______________________________________________________________ 37

7. Household Debt _____________________________________________________________________________ 38

8. House Prices _________________________________________________________________________________ 39

9. Financial Soundness Indicators, 2013:Q3 ____________________________________________________ 40

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

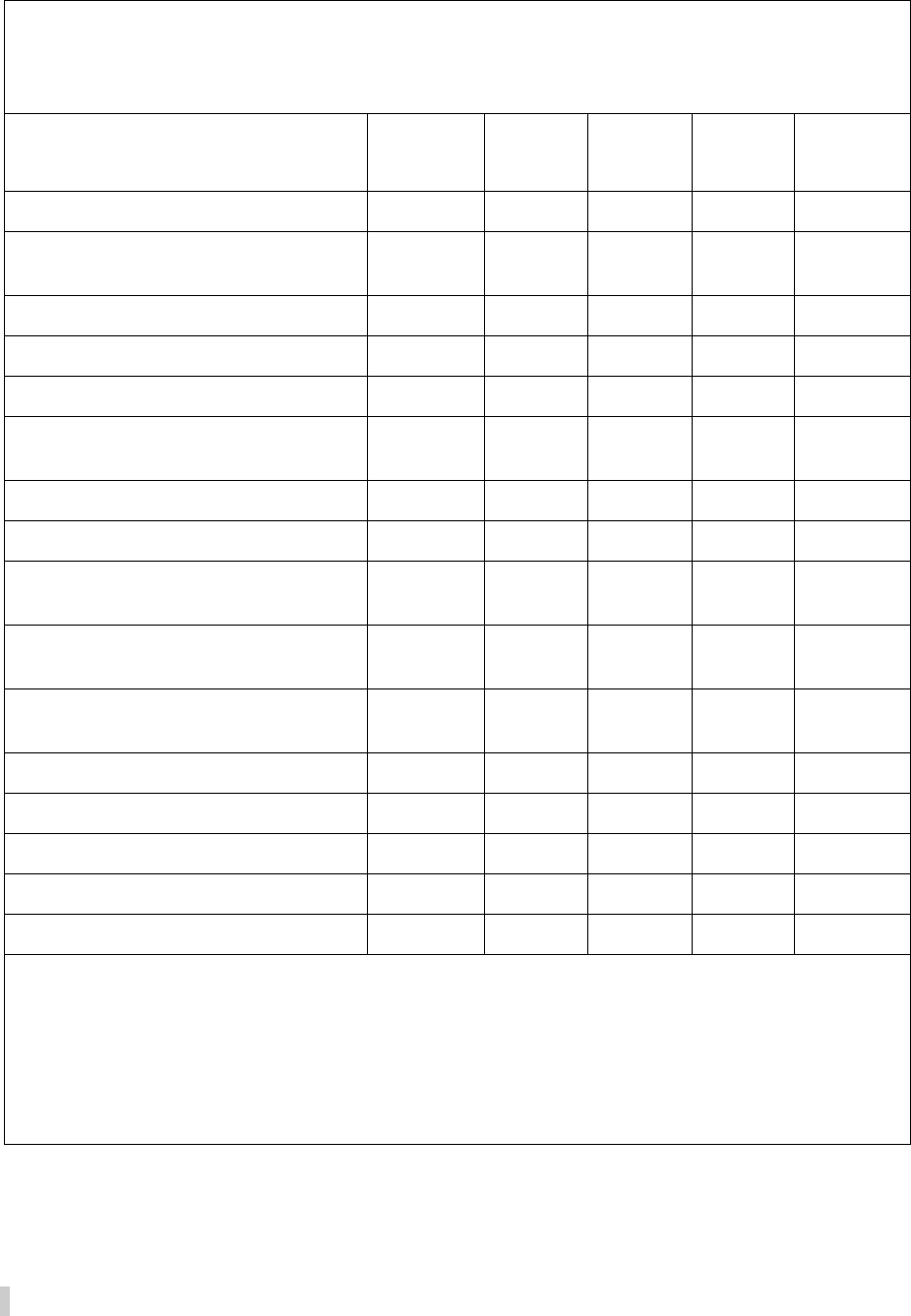

TABLES

1. Selected Economic and Financial Indicators, 2009–14 _______________________________________ 41

2. Indicators of External Vulnerability, 2008–12 ________________________________________________ 42

3. Balance of Payments, 2009–14 _______________________________________________________________ 43

4. Illustrative Medium-Term Economic Framework, 2009–18 ___________________________________ 44

5. Summary of Federal Government Operations and Stock Positions, 2009–14 ________________ 45

6. Monetary Survey, 2009–13 ___________________________________________________________________ 46

7. Banks’ Financial Soundness Indicators, 2009–13 _____________________________________________ 47

8. Macroprudential Measures Since 2010 ______________________________________________________ 48

APPENDICES

1. Staff Policy Advice from the 2011 and 2012 Article IV Consultations ________________________ 49

2. Risk Assessment Matrix ______________________________________________________________________ 50

3. External Sector Assessment __________________________________________________________________ 51

4. Public Debt Sustainability Analysis ___________________________________________________________ 56

5. External Debt Sustainability Analysis _________________________________________________________ 63

6. 2013 FSAP—High Priority Recommendations _______________________________________________ 66

7. Stress Tests of Banking, Household and Corporate Balance Sheets _________________________ 67

8. What Explains Malaysia’s Resilience to Capital Outflows? ___________________________________ 70

9. Transformation Plans to Boost Growth and Inclusion ________________________________________ 74

MALAYSIA

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS, OUTLOOK, AND RISKS

1. Context. General elections were held on May 5, 2013. Prime Minister Najib’s incumbent

coalition won narrow election, thus ensuring smooth policy transition. Amidst a difficult external

environment for Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) last spring-summer, the administration has

taken actions that signal its resolve to respond decisively to domestic and external challenges. A

High-Level Fiscal Policy Committee (FPC) was created to improve management of the public

finances, food and fuel subsidies and electricity tariffs are being rationalized, and a Goods and

Services Tax (GST) will be introduced in 2015. These measures are key steps towards rebuilding fiscal

buffers lost on account of expansionary policies during the global financial crisis.

2. Economic developments. Growth

slowed to 4.7 percent in 2013, compared

with 5.6 percent in 2012, but remained

healthy. Weak external demand, especially

in the first half of the year, weighed on

activity, and a small negative output gap

opened up. Domestic demand remained

robust, supported by healthy labor markets,

accommodative financial conditions and,

during the first half, expansionary fiscal

policies (Figure 1). Inflation remained

subdued through the spring and summer

despite the introduction of a minimum

wage in 2013 but picked up recently. Headline inflation rose to 3.2 percent year‐on‐year in

December, reflecting subsidy cuts. Core inflation has also increased but is still very low, less than

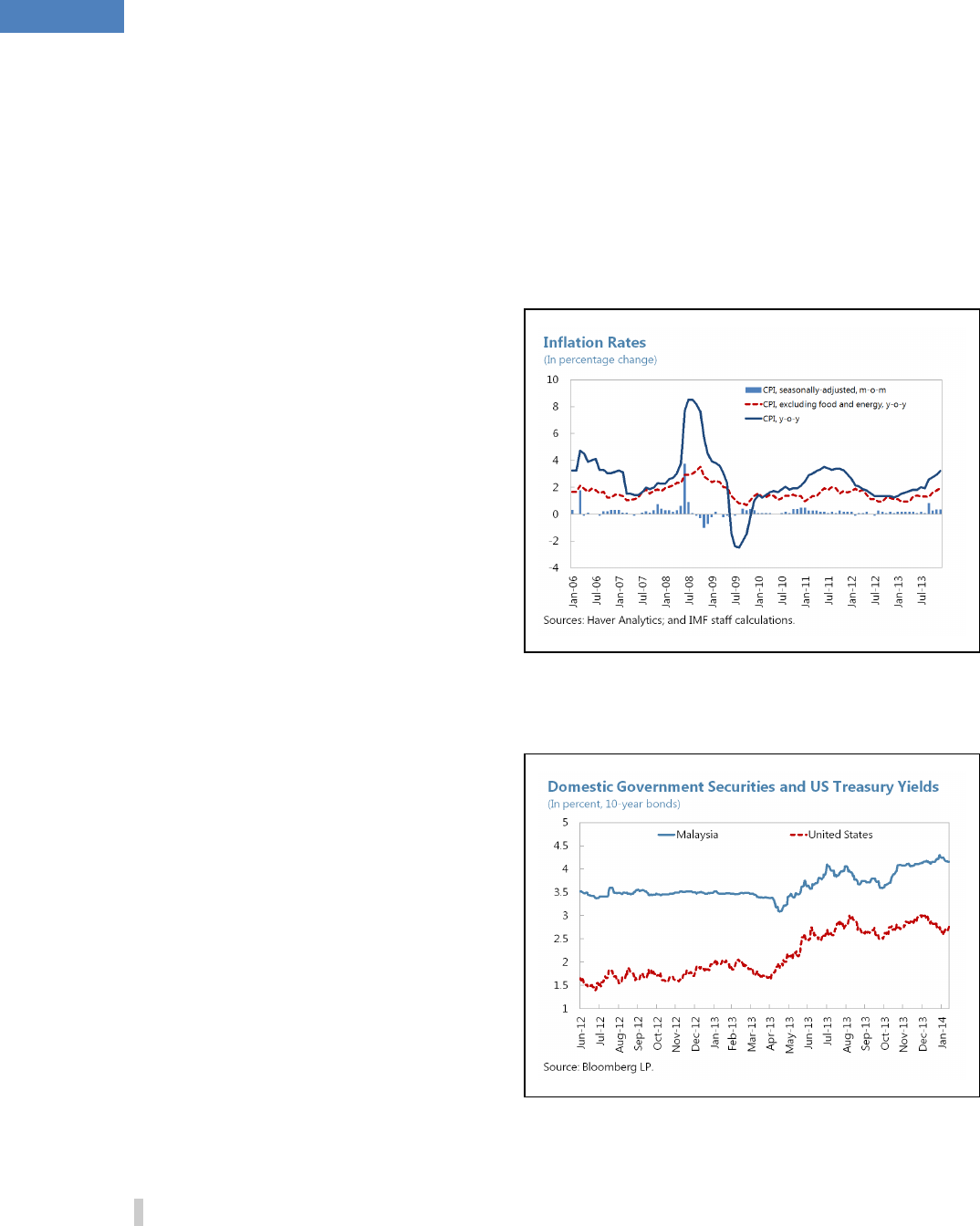

2 percent in December (Figure 2).

3. Financial Market Developments.

Like many other EMEs, Malaysia has been

experiencing capital outflows during

periods of market turbulence, including

spring-summer and early this year. Between

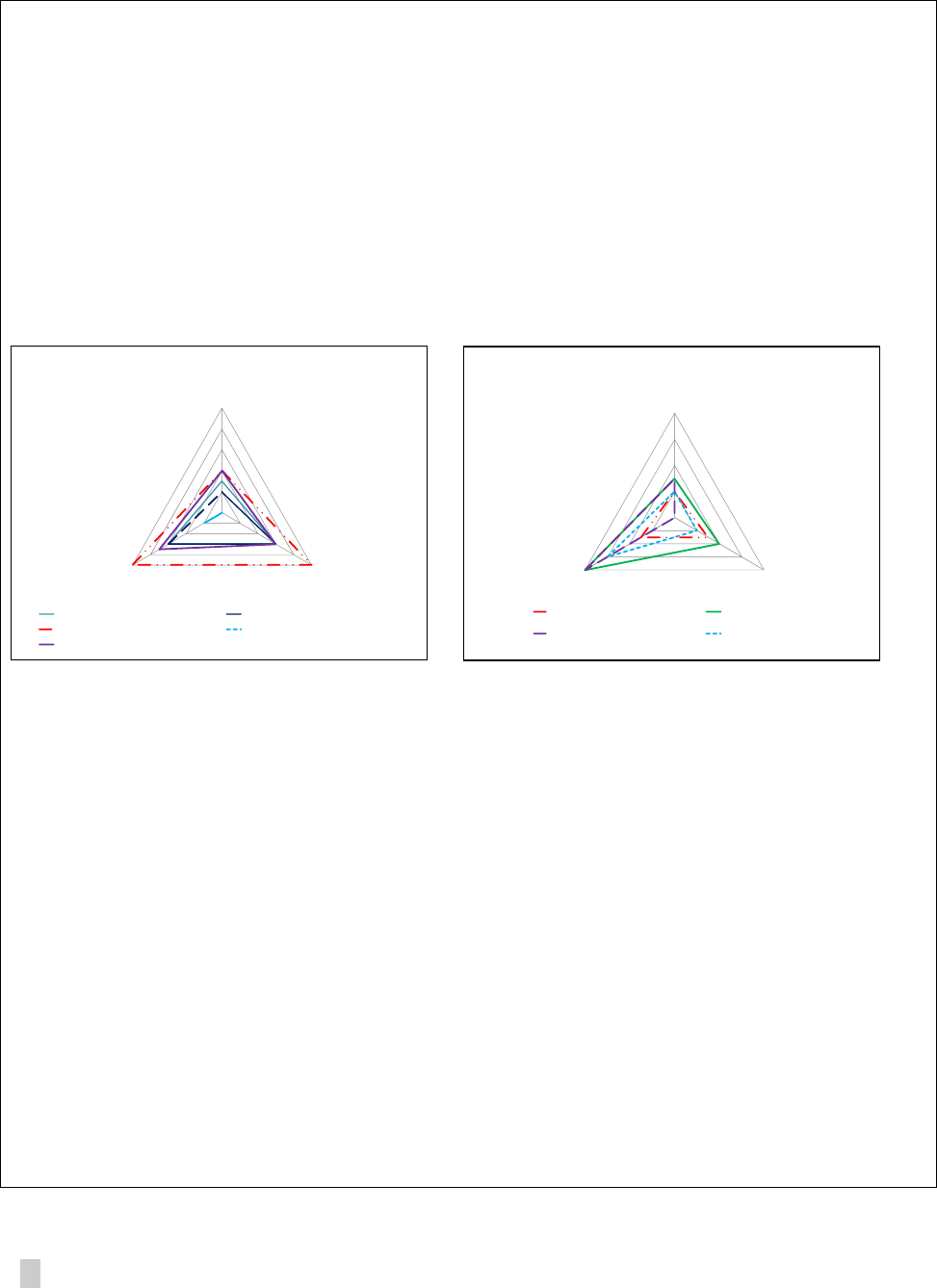

end¬May and end¬2013, the yield curve for

Malaysian Government Securities (MGS) has

steepened: 10‐year yields have increased by

70 bps, and the spread against the

U.S. dollar has widened by about 20 bps.

During summer turbulence, the ringgit

weakened by about 11 percent against the

dollar (peak-to-trough) and after a brief

period of strengthening is now back below the September

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

trough. Deep financial markets and a flexible exchange rate have helped facilitate financial

adjustment, and the economy has been able to absorb the shocks without appreciable harm to date.

4. Outlook. Growth is projected to accelerate to 5.0 percent in 2014. Consumption and

investment growth are expected to moderate somewhat but should generally hold up amidst

conditions of full employment and the long pipeline of large, multiyear investment projects. In

addition, the pickup of export growth since the second half of 2013 should be sustained as the

global economy continues to improve, and offset headwinds from fiscal consolidation (a fiscal

impulse of about minus 1 percent of GDP in 2014, although staff views the fiscal multipliers as low).

Over the medium term, growth is expected to average 5 percent, reflecting higher investment,

including infrastructure upgrades, which should help boost productivity. The gradual removal of

subsidies is expected to result in a modest increase in inflation during 2014. Second round price

effects are, however, expected to be limited in light of the low initial level of inflation, and BNM’s

considerable monetary policy credibility. Inflation will likely reach about 4.0 percent in 2015

following the introduction of GST, but in staff’s baseline scenario, is expected to gradually moderate

to below 3.0 percent in the medium term.

5. Risks. The risks to the staff’s baseline scenario are primarily on the downside and stem from

both external and domestic sources (Appendix 2).

External risks. A key risk is a potentially bumpy exit from unconventional monetary policies

(UMP) in advanced economies (AEs), which could trigger bouts of financial market turbulence

and dampen external demand. With foreign investors still holding sizeable positions in the

domestic bond and equity markets, Malaysia is vulnerable to capital outflows during periods of

heightened global financial stress, as evidenced during spring-summer 2013. Other risks include

a further slowdown in China, a protracted period of slow growth in Europe, and commodity

price shocks.

Domestic risks. The relatively high level of federal debt (close to the government’s self-imposed

ceiling of 55 percent of GDP) and large contingent federal liabilities limit the room for

countercyclical fiscal policy. And while recent fiscal actions are welcomed, there remain

implementation risks associated with these comprehensive reforms. In particular, setbacks in the

implementation of fiscal reforms could undermine investor sentiments and trigger outflows from

the bond market and a jump in yields which, in the context of the government’s high financing

needs, could have a significant macro-fiscal impact. In staff’s view, however, implementation

risks are low—the authorities have demonstrated the political will and possess the technical

expertise to carry reforms out. In addition, high house prices, rising household debt, and banks’

large exposure to real estate remain a concern, particularly in light of UMP unwinding and a

likely tightening in domestic financial conditions and higher interest rates. Other domestic risks

include a higher and more persistent increase in inflation and inflation expectations, triggered

by higher fuel and electricity prices as subsidies are being rationalized. Adjustments in fuel

prices are expected to add about 0.5 percentage point to annual inflation in 2014−15, while the

GST could add about 0.9 percentage point in 2015. The low starting level of inflation and the

MALAYSIA

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

substantial policy credibility of the monetary authorities, circumscribe, in staff’s view, the risk of

second round effects.

6. Policy advice. The authorities are taking decisive and proactive steps to reinforce Malaysia’s

macroeconomic and structural policies (Appendix 1). While specific measures are consistent with

Fund policy advice, they are home grown and driven by the authorities’ own multiyear adjustment

and reform programs. Specifically, the authorities took action to strengthen Malaysia’s public

finances during the second half of 2013. These measures are framed in the context of a medium

term fiscal adjustment program and are consistent with past Fund technical assistance and staff

policy advice. The authorities are carefully monitoring financial sector risks and are implementing

additional macro prudential measures; they are also in the process of strengthening their

information base through the collection of granular data on household assets and liabilities. The

authorities are allowing two-way exchange rate flexibility. They are also implementing wide ranging

structural reforms, and their specific programs benefit from extensive technical and policy support

from the IMF and other international organizations.

7. Authorities’ views. The authorities were in broad agreement with staff’s assessment of the

economic outlook and balance of risks.

They anticipate growth to increase in 2014 with the improvement in the external environment,

although the fiscal consolidation can be expected to be a drag on growth. Private investment

growth should remain robust at about 13 percent but some moderation in private consumption

growth is likely.

The authorities also see the main risks to the outlook are being primarily on the downside and

they highlighted risks from external sources, with a slowdown in global growth a key concern. In

addition, uncertainty surrounding the unwinding of UMPs and the potential for policy missteps

along the way and heightened volatility are also key risks for Malaysia.

On the domestic front, the authorities reiterated their commitment to steadfast implementation

of fiscal reforms. The authorities acknowledged the risk of spillover to prices of other nonfuel

goods and services from subsidy rationalization, which will raise headline inflation (albeit from

low starting levels). They assess the risk of second-round effect at this point to be limited.

The authorities are less concerned with risks to financial stability from high household debt and

house prices. They pointed to the large cushions provided by high levels of household financial

assets, healthy labor markets and low risk of unemployment. In addition, mortgage interest rates

are largely tied to the policy rate (indirectly through the base lending rate), which has been

relatively stable and makes sudden increases unlikely. Lastly, the authorities’ targeted and

phased approach to macroprudential policies, along with efforts to increase financial literacy,

has curtailed risks.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

NEAR-TERM ECONOMIC POLICIES: ACHIEVING A

SMOOTH TRANSITION

8. Policy mix. The authorities’ policy mix is appropriate in the present conjuncture, in which

Malaysia’s priority is to address fiscal vulnerabilities against a backdrop of low inflation, and an

improving external environment that is nevertheless still subject to large uncertainties and potential

capital flow volatility. The decisive, yet gradual tightening of fiscal policy should help Malaysia maintain

market access at low funding costs while avoiding undue damage to economic growth or igniting higher

inflation. The slightly accommodative monetary policy stance has been appropriately supportive of

growth in the context of low inflation, a small negative output gap and, until mid‐May 2013, strong

capital inflows. Going forward, however, monetary policy may need to be recalibrated as UMPs unwind

and if inflation risks rise. The tightening of macroprudential policies to date appears to have helped to

address potential financial stability risks, but continued monitoring is appropriate and additional

measures may be needed.

9. Fiscal policy. Following the market turmoil in spring-summer, the federal government

recalibrated fiscal policy in September-October and is on track to reach its fiscal deficit target of

4.0 percent of GDP in 2013.

1

According to staff projections, fiscal adjustment in 2013 was significant

(about 1 percent of GDP), driven by higher income taxes and lower development spending. Current

spending, which has increased considerably in recent years, driven by wages and subsidies, was higher

than budgeted in 2013 but is expected to remain stable relative to GDP. In particular, spending on

subsidies, which increased by 0.6 percentage points of GDP in 2012, is expected to remain elevated

in 2013 and would have been higher in the absence of the fuel price adjustments implemented in

September. The 2014 federal deficit target of 3.5 percent of GDP seems feasible if, as assumed in the

staff’s baseline projection, growth in current spending is contained within a tight envelope and fuel

prices are increased further during the year (Figure 4). Oil revenues are projected to decline by

0.5 percent of GDP, in line with a projected decline in international oil prices. Under the staff’s baseline

projection, fiscal adjustment in 2014 will be driven by subsidies (about 1 percent of GDP), the wage bill,

while development spending as percent of GDP will also slow down.

23

The fiscal impulse (based on staff’s

1

The authorities' measure of the overall fiscal balance differs from staff’s (net lending/borrowing) due to differences in

methodology/basis of recording (Government Finance Statistics Manual 2001 versus the authorities’ modified-cash based

accounting), and differences in the treatment of certain items. These reasons account for a 0.4−0.7 percentage point

difference in the measured fiscal deficits for 2012−13.

2

The decline in fuel subsidies is driven by the carry-over effect of the September fuel price adjustments (0.4−0.5 percent

of GDP). Staff assumes in its baseline projection an additional 20 sen hike to take place in mid-2014 with a half-year yield

of 0.2-0.3 percent of GDP, which will be partially offset by higher direct cash transfers.

3

Malaysia’s development budget is determined for five year intervals and the current budget allocation covers the five

year period ending in 2015. The 11

th

Malaysia plan, to be announced in 2015 will cover development spending during

2016-2020.

MALAYSIA

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

definition of fiscal balance) is about minus 1 percentage point of GDP.

4

Its impact on growth is

expected to be relatively small, given that a significant share of the adjustment comes from subsidy

rationalization, whose fiscal multipliers are low. The public sector deficit has widened in recent years,

reaching 5 percent of GDP in 2012, and is expected to be about 6½ percent of GDP

during 2013−2014. The increase in the public sector deficit was driven in part by higher development

spending by Nonfinancial Public Enterprises (NFPEs), which has offset the decline in development

spending at the federal government level. Fiscal impulse at the broader public sector level was

positive in 2013 but is expected to turn negative in 2014.

10. Monetary policy. Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) has kept its policy rate unchanged at

3 percent since May 2011 (Figure 3). This policy stance, reflecting BNM’s dual mandate of ensuring

medium-term price stability and sustainable

growth, kept real interest rates low and

supported growth, against a backdrop of

uncertain global growth prospects and low

domestic inflation rates. Looking ahead, staff

expects BNM to begin a gradual tightening

cycle. The gradualist approach is warranted by

the unusual degree of uncertainty around the

external environment and is also consistent

with the need to safeguard domestic financial

stability in an environment of high household

debt. Furthermore, while inflationary

expectations are well anchored at present, the succession of price increases stemming from subsidy

rationalization and the introduction of the GST

4

Fiscal impulse is defined as the change in cyclically-adjusted Federal Government overall balance as percent of

potential GDP.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

could lead to a pickup in inflation expectations. BNM’s task in the near term is to allow pass-through

of cost-related increases in prices (cost‐push inflation) while detecting and preempting, in a timely

and decisive fashion, any second round effects from becoming embedded in the wage-price

structure.

11. Macroprudential policies (MAPs). BNM’s current monetary policy stance is supported by

macroprudential policies to curtail financial stability risks from rapid increases in household debt

and house prices (see Box 3). Household debt reached 83 percent of GDP at end-September 2013,

up from 55 percent five years earlier. Over half of the debt is on residential property, of which nearly

70 percent is contracted at variable rates tied to the Base Lending Rate (BLR), although lending rates

have fallen recently even as the BLR has remained unchanged. Starting in November 2010 and

continuing, most recently, with the 2014 budget in October 2013, the authorities have imposed a

series of targeted, gradual, and escalating MAPs, which have been mainly directed at speculative

purchases of homes and unsecured credit (see Table 8). The 2014 budget also addressed

affordability issues through special financing schemes and measures to raise the supply of

affordable housing.

5

There are early signs that the more recent measures have slowed down the

approval of new loans and begun to cool the housing market; however, some inertia in loan growth

due to drawdowns of loans already committed can be expected. Should credit growth remain

strong, additional MAPs should be introduced, and their scope and stringency should depend on

the evolving stance of monetary policy, and they should be carefully designed to ensure

effectiveness and avoid circumvention. Options for additional macroprudential measures include

capping loan-to-value ratios (LTV) on second and first mortgages, explicit limits on debt

service-to-income ratios, or additional capital charges on high LTV loans.

12. Risks to the baseline and policy responses. In the present “inflection point” for growth in

EMEs, staff’s baseline scenario is subject to a wider-than-usual range of uncertainty. Should the

growth outlook deteriorate significantly, the flexible exchange rate can act as a shock absorber and

there is ample room for BNM to cut its policy rate to support growth. However, relatively high fiscal

deficit and public debt levels afford limited space for a sustained countercyclical fiscal response. Any

fiscal stimulus should be temporary, targeted and anchored in a credible medium term fiscal

consolidation program. Importantly, structural reforms and the all important subsidy rationalization

and GST implementation should not be delayed or compromised as sound public finances are

paramount to macrofinancial stability. Exchange rate flexibility, complemented by foreign exchange

intervention to smooth excessive volatility, should be the main response to unpredictable capital

flows.

13. Authorities’ views. The authorities reiterated their commitment to meeting their fiscal

targets, and to press ahead with subsidy rationalization and the implementation of the GST. The

5

The Private Affordable Ownership (MyHome) Scheme was introduced to incentivize private developers to build

more low- and medium-cost houses, with the subsidy provision of up to RM 30,000 per unit built. A total of

RM 300 million has been allocated in 2014 for the construction of 10,000 housing units. For Perumahan Rakyat

1Malaysia (PR1MA), the government has allocated RM 1 billion to provide 80,000 units of affordable housing to

middle income households (combined income of RM 2,500−7,500 per month) for homes in the RM 100,000−400,000

price range.

MALAYSIA

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

creation of the high-level FPC provides additional assurance that Malaysia will push through with

sound fiscal policies to ensure fiscal sustainability while safeguarding growth. The authorities view

the current monetary policy stance as supportive of growth but acknowledged the risk to inflation

from subsidy rationalization. Inflation developments are closely monitored, both in terms of the

pervasiveness and persistence of price increases across all items of the CPI basket, using various

qualitative and quantitative indicators including the newly developed survey of price expectations. In

terms of the impact of unwinding of UMPs in AEs, the authorities welcomed the prospect of

recovery in AEs and normalization of global interest rates as beneficial for Malaysia but were

concerned about potential volatility and capital outflows. A monetary policy response to the

unwinding of UMPs would depend on the implications to the overall outlook for growth and

inflation for the Malaysian economy.

FISCAL POLICY: A BREAKTHROUGH

14. Background. The authorities took vital steps to shore up fiscal management and policy in

the second half of 2013, and signaled their commitment to secure medium-term fiscal targets in

the 2014 Budget. Fiscal management and institutions were strengthened substantially by the

establishment of a high-level FPC (Box 1). In addition, subsidies on fuel, electricity, and sugar are

being rationalized, and a GST will be introduced in April 2015 (Box 2). To mitigate the impact of

fiscal consolidation on the poor, the authorities are taking steps to strengthen the social safety net

by enhancing the existing cash transfer program to lower income groups. The authorities are

committed to their large and complex fiscal reform agenda and are striving to carefully design and

execute it in order to mitigate implementation risk.

15. Fiscal sustainability and medium-term fiscal adjustment. The authorities’ decisions

in 2013 are tantamount to a fiscal policy breakthrough aiming to contain federal debt and related

fiscal risks. Federal debt has risen significantly in recent years, to an estimated 54.8 percent of GDP

at end-2013, from about 40 percent of GDP at the start of the global financial crisis. Based on staff’s

debt sustainability analysis (see Appendix 4

), under a no adjustment scenario (the constant primary

balance scenario), the federal debt-to-GDP ratio would exceed the authorities’ self-imposed debt

ceiling of 55 percent in the medium-term and would continue to increase thereafter.

16. Staff position. Staff welcomes the authorities’ comprehensive fiscal reform package, which

is well timed, appropriately paced, and allows sufficient preparation time for the introduction of the

GST, including an all important public education campaign. The authorities’ plans to strengthen the

social safety nets by better targeting them are also welcome. Finally, the management of fiscal

policy has been strengthened by the establishment of the high-level FPC. Implementation and

political risks from fiscal reforms are, in staff’s view, circumscribed by the authorities’ commitment to

the reforms and by their sound preparation and technical plans to carry them out. Fiscal reforms are

a marathon, not a sprint, and the large unfinished agenda in this area requires careful design and

execution in order to mitigate implementation risk.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

17. Staff supports the authorities’ plans to reduce the federal deficit to 3 percent by 2015, and to

about zero by 2020. The proposed fiscal adjustment signals the authorities’ commitment to fiscal

consolidation and is

appropriately paced, with

significant frontloading that

is commensurate with the

need to rebuild fiscal buffers.

Under the mission’s baseline

assumptions, a cumulative

improvement of about

4 percent of GDP in the

cyclically-adjusted primary

balance is required in order

to lower the federal debt-to-

GDP ratio to its pre-crisis

level of about 40 percent.

This medium-term debt

target is needed to rebuild

buffers to allow for

countercyclical fiscal policy,

absorb contingent liabilities, and ensure that the debt to GDP ratio remains below 55 percent.

6

The authorities’ target of reducing the deficit to 3 percent of GDP by 2015 is feasible if, as assumed

in staff’s baseline, the GST is implemented and fuel price subsidies are rationalized. However, further

measures will be needed beyond 2015 to balance the federal budget by 2020 as oil revenues are

projected to decline and nondiscretionary expenditures are expected to rise. Spending pressures will,

inter alia, arise from civil service pensions and other aging-related costs; the need to repay previous

off-budget stimulus spending; and other federal obligations, such as spending on the Mass Rapid

Transit (MRT) project.

7

In this context, staff supports the authorities’ plan to further elaborate,

quantify and communicate their medium term fiscal consolidation strategy.

To achieve the authorities’ fiscal targets for 2020 and generate sustained fiscal savings, staff

elaborated a medium-term fiscal strategy that relies on revenue and expenditure instruments with a

desirable mix of stabilization, efficiency, growth, and distributional characteristics (see Box 3 and

Selected Issues Paper on Malaysia’s medium-term fiscal strategy). These characteristics include low

fiscal multipliers; reduced reliance on corporate and oil revenues; and a progressive (or at least less

regressive) distributional impact. This fiscal strategy should also be underpinned by concrete

structural reforms to promote efficiency, growth and equity.

6

The 2012 Malaysia Article IV report (Box 4) details the medium-term debt target and staff’s stochastic Debt Sustainability

Analysis (DSA).

7

MRT is a public infrastructure project that is funded off-budget through a special vehicle that enjoys a federal guarantee;

given the non-commercial nature of the project, it may be assumed that a fraction of the debt repayments associated with

the MRT will be eventually funded through the budget.

Potential Yield

Description (Percent of GDP)

Revenue measures

GST

Broaden the tax base through revising the list

of zero-rated and exempt goods. Increase GST

rate from 6

percent to 8

percent.

1

-

1.5

Property taxes Broaden recurrent property taxes 0.3

-

0.5

Expenditure measures

Rationalize non-fuel subsidies

Rationalize subsidies on rice, flour and cooking

oil and partially replace them with targeted

transfers.

0.2

-

0.3

Restrict wage growth

Continue to limit the establishment of new

posts, restrict bonus payments and achieve

savings in emoluments in the education sector.

0.2

-

0.5

Reduce inefficiencies in spending

Continue efforts to improve procurement,

improve efficiency of education spending and

spending on social safety nets.

0.5

-1

Malaysia: Potential Revenue and Expenditure Measures Beyond 2015

MALAYSIA

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Viewed from this perspective, the authorities’ plans to date to rationalize subsidies, introduce a

GST, increase transfers and improve their targeting, and protect public investment spending are

a step in the right direction. Staff also argued that there was a need to restrict wage growth and

improve the efficiency of public spending in general, and education spending in particular.

Finally, staff recommended raising contributions to the Civil Service Pension Fund (KWAP) to

reduce the unfunded portion of federal pension liabilities and consider other measures to

address its long-term sustainability.

8

18. Tax policy. Staff strongly welcomed the authorities’ efforts to implement the GST, which

should help to broaden the tax base and reduce reliance on oil and gas revenues over time (Box 3).

The GST should also help reduce informality and improve tax buoyancy.

9

The net revenue yield from

GST, estimated at about 0.3 percent of GDP, is however expected to be relatively small initially. This

is due to the relatively low standard rate, the reduction of income taxes and other offsetting

measures adopted in the 2014 budget.

Staff argued that, small initial revenue gains notwithstanding, the GST provides a powerful and

flexible revenue-generating mechanism to respond to future economic shocks. If needed, GST

base broadening, including the reduction of GST exemptions and zero-rated goods, should take

precedence over increasing the standard rate.

10

Staff strongly urged the authorities to resist

pressures to expand the list of exempt and zero-rated goods to ensure that the efficiency of GST

is not compromised.

Staff argued that recurrent property taxes, a growth-friendly and progressive revenue source,

are currently underutilized in Malaysia relative to its peers and could also be used to broaden

the revenue base going forward.

11

The authorities are also conducting an assessment of the effectiveness and costs of tax

incentives. Staff recommended better targeting of incentives based on this cost-benefit analysis.

8

The pension scheme for civil servants, Kumpulan Wang Persaraan (KWAP) is a defined benefit scheme that is

partially funded by the budget, unlike the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), the scheme for private sector workers

which is a fully funded defined contribution scheme. KWAP was incorporated in 2007, taking over the assets and

liabilities of the Pension Trust Fund, which the government had established in 1991 to help fund its future pension

liabilities. KWAP covers employees who joined civil service after 1991 (pension liabilities of civil servants who joined

before 1992 are funded on a pay-as-you-go basis from the budget). KWAP was intended to be fully funded, by

contributions from federal, state and local governments; however, federal contributions are currently below levels

consistent with full funding.

9

Being a value-added tax, the GST generates relevant information on different tax payers along the production

chain.

10

As a general principle, minimizing the number of GST exemptions, including at the implementation stage, is crucial

to improve efficiency (already at the implementation stage).

11

Taxes on financial and property transactions and other property-related taxes are about 1.1 percent of GDP in

Malaysia, which is lower than the median of 1.6 percent of GDP in OECD countries.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

19. Subsidy reform. At over 10 percent of

federal spending, fuel subsidies are regressive and

costly to the budget. Staff welcomed the price

adjustments announced in September as a first step

in replacing them with more targeted transfers to

low-income Malaysians.

12

Staff made the following

recommendations:

Gradual but credible rationalization of fuel

subsidies and a switch, eventually, to an

automatic price adjustment mechanism for fuel

prices would ensure that fiscal savings are

preserved and the issue is depoliticized.

13

The authorities’ plans to gradually reduce off budget

subsidies on natural gas and electricity are also critical in this regard. Bringing on budget these

implicit subsidies would improve the transparency of fiscal policy, and could bolster support for

subsidy reform.

Cash transfers (Bantuan Rakyat 1Malaysia (BR1M)), first introduced in 2012, were increased

subsequently, their eligibility criteria were broadened, and these transfers now benefit over

55 percent of households. Staff noted that it would be desirable to improve the targeting of

welfare transfers under different programs and welcome steps to create a comprehensive

database on welfare recipients and programs, as announced in the 2014 budget.

20. Fiscal risks. Despite important recent progress, Malaysia still faces significant fiscal risks.

Continued reliance on oil and gas revenues is a medium term risk to debt sustainability in view of

the depletion of the oil and gas resources over time. Oil price shocks or exchange rate shocks can

lead to unanticipated increases in the subsidy bill, offsetting the savings from domestic price

adjustments. Federal contingent liabilities are sizeable, with loan guarantees alone amounting to

15 percent of GDP.

14

In staff’s view, the FPC, which will be in charge of endorsing medium-term fiscal

targets and strategy, should also play a critical role in monitoring, assessing, and managing fiscal

risks going forward. In this context, staff

12

Prices of gasoline and diesel were raised by 20 sen per liter in September, reducing the price gap (the difference

between market price and subsidized price) from 30 to 23 percent for gasoline and from 36 to 29 percent for diesel.

After the adjustment in September, there is still a subsidy of 63 sen per liter for gasoline (RON 95) and 80 sen per

liter for diesel.

13

Staff assumes in its baseline scenario that fuel prices are gradually increased to reach parity with international

prices by end-2016.

14

Federal contingent liabilities include loan guarantees (15 percent of GDP), potential obligations under user-funded

PPPs, liabilities of NFPEs, insured deposits under the deposit insurance, the deposits of some development finance

institutions and government linked investment funds, and credit guarantee schemes. About 20 percent of loan

guarantees are to statutory bodies and the rest are to public companies.

MALAYSIA

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Argued for anchoring budget targets on the nonoil primary balance, which would help insulate

the budget from these risks and also reduce the procyclicality of spending.

Supported efforts to improve the monitoring and management of loan guarantees and other

contingent liabilities, and recommended preparing a fiscal risks statement to be published with

the budget documents.

Highlighted the risk that as federal gross debt approaches the government’s self-imposed

ceiling, there could be pressure to push spending off-budget, which would undermine the

credibility of the formal budget process and the medium term fiscal consolidation.

Supported reforms to strengthen public financial management, including adopting accrual

accounting, introducing a medium-term fiscal framework, and reducing the use of

supplementary budgets, some of which are already underway.

Welcomed the authorities’ efforts to improve public procurement and move towards

performance-based budgeting.

21. Authorities’ views. The authorities stated their commitment to a medium-term fiscal

consolidation, including subsidy rationalization and the introduction of the GST in 2015,

underpinned by efforts to strengthen fiscal management and institutions and other structural

reforms. The authorities emphasized the importance of adopting a gradual approach in

implementing fiscal adjustment and subsidy rationalization, and the need to protect vulnerable

households. In their view, implementation risks are small, as evidenced by the political commitment

at the highest level to these reforms and the high level of their technical preparedness. They agreed

with staff on the need to outline a medium-term fiscal plan, to be endorsed by the FPC, and

indicated that work was underway to formulate a medium-term fiscal plan. The authorities stated

that although federal loan guarantees have increased recently, government’s loan guarantees are

primarily to commercial nonfinancial public enterprises with evident capacity to service debt, and

that contingent liabilities should be analyzed taking into account their (low) probability of default.

FINANCIAL STABILITY

22. Background. The 2012 IMF-World Bank Financial Assessment Program (FSAP) found that

Malaysia’s financial system is sound and backed by a strong supervisory and regulatory system.

Malaysia’s financial system is well diversified although banks continue to provide over 85 percent of

credit domestically. Nonbanks, including development financial institutions, provide the remaining

15 percent of credit but constitute only 9 percent of financial system assets. Consistent with the

FSAP, staff found that Malaysian banks are well-capitalized, profitable, and have adequate liquidity

buffers. With a Tier 1 capital ratio of 13.9 percent at end-2012, banks are well-positioned to meet the

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

Basel III target of 8.5 percent by 2019.

15

Banks’ liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) of 60 percent is consistent

with the 2015 Basel III target but meeting the 2019 target of 100 percent, while attainable, is more

challenging under current definition.

16

Banks’ funding structure is dominated by deposits, which make

up 80 percent of the total; 17 percent of these deposits are classified as strictly callable. Banks are

moderately profitable, with return on equity averaging about 14 percent in recent years, although

recent heightened competition for retail deposits has compressed net interest margins.

17

Looking

ahead, banks’ funding costs are likely to increase as deposit rates rise with the unwinding of UMPs but,

with variable rate loans largely tied to the BLR (which has tended to only change when the OPR

changes), banks could face further compression of their net interest rate margins.

18

23. FSAP update. Staff noted that the authorities have made significant progress with

implementation of the recommendations of the FSAP (see Appendix 6). Notably, the Financial Services

Act (FSA) and the Islamic Financial Services Act (IFSA) came into force on June 30, 2013, strengthening

BNM’s powers, including the ability to take prompt corrective action for financial institutions and to

carry out consolidated supervision of financial holding companies. In addition, the regulatory

perimeter is widened to include onshore nonbank financial entities and nonbank financial entities

operating in the offshore

15

The decline in banks’ CAR from 17.6 percent at end-2012 to 14.7 percent at Q3:2013, is reflective of banks’ efforts to

reduce capital that no longer qualifies as loss-absorbing capital under Basel III. The Tier 1 capital ratio of the banking

system, the relevant Basel III metric, has remained stable over this period.

16

Liquidity as measured by one-year coverage of liabilities with assets has come down slightly since 2012 but remains

similar to the 2011 level. Under the LCR, the more stringent Basel III definition of liquidity, that measures one-month

coverage of liabilities, banks are consistent with the global phase-in schedule.

17

Banks’ spreads between lending and deposit rates have shrunk over the past 10 years (by about 100 bps) as lending

rates have come down faster than deposit rates, reflecting, in part, increasing competition in the banking sector and

improving borrower creditworthiness (as evidenced by falling amounts of impaired loans for the overall system).

18

However, BNM issued an industry consultation paper in January 2014 proposing a new reference rate to replace the

BLR. The proposed new reference rate is designed to reflect each financial institution’s funding costs, enhancing

transparency in setting the reference rate, and increasing the sensitivity of the reference rate to changes in an

institution’s funding costs, which will reduce their risk.

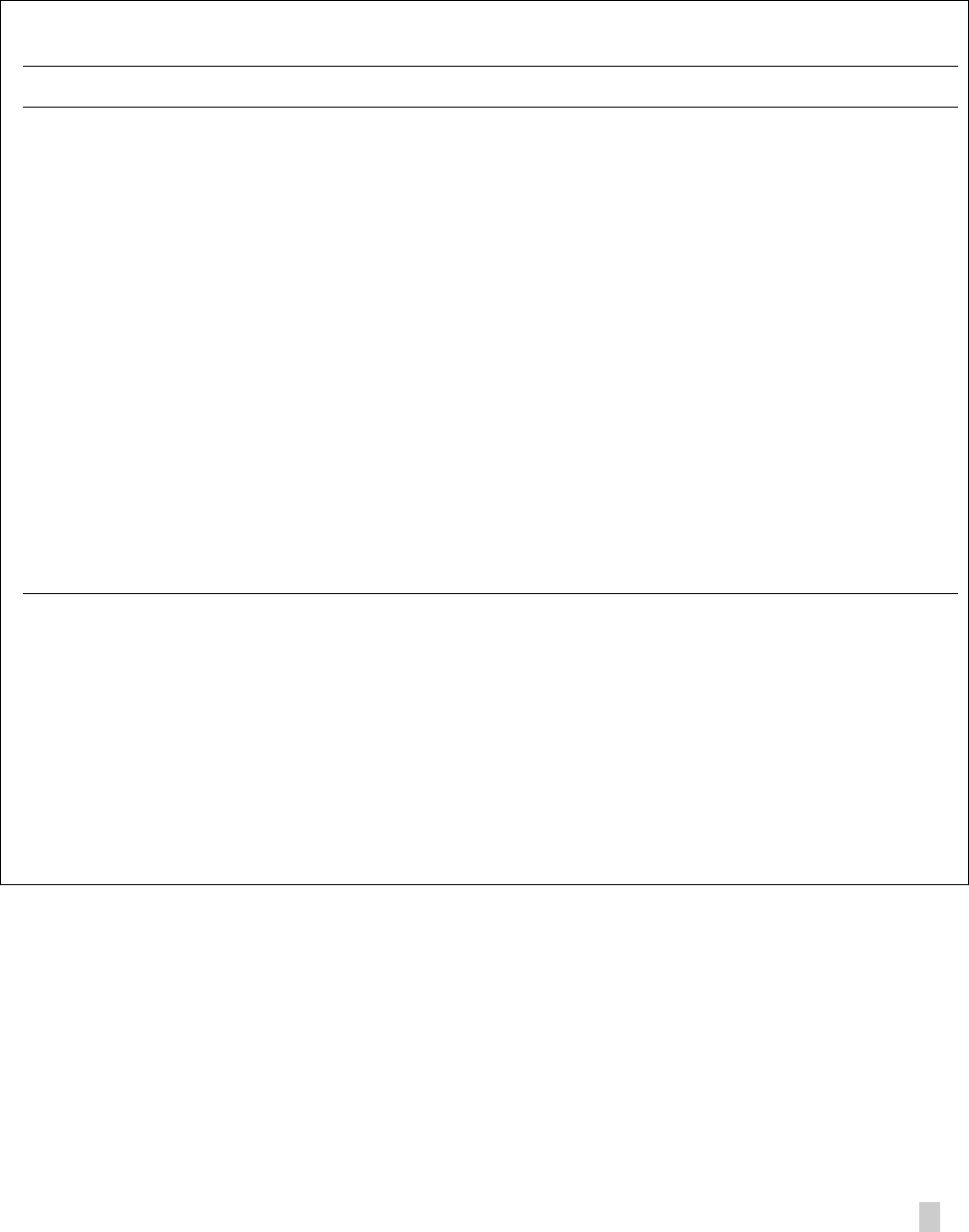

0

2

4

6

8

10

Sovereign CDS spread

(bps)

Private domestic credit

growth (percent y/y)

Regulatory Tier 1

Capital to Risk-

Weighted Assets

Non-performing loans

(NPL) ratio

Liquid assets to short-

term liabilities

Gross portfolio inflows

to GDP

2012Q3

2013Q3

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics and Financial Soundness

Indicators; Bloomberg LP.; Haver analytics; and IMF staff calculations.

1/ Away from center signifies higher risks, easier monetary and financial

conditions, or higher risk appetite.

Malaysia: Macrofinancial-Environtment Spidergram 1/

MALAYSIA

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Labuan International Business and Financial Center (Labuan IBFC) other than those licensed by the

Labuan Financial Services Authority. The IFSA provides a legal framework that is consistent with

Shariah on regulation and supervision, from licensing to the winding up of institutions. Separately, a

high-level committee, the Financial Stability Executive Committee, comprising the BNM, Perbadanan

Insurans Deposit Malaysia (PIDM), and the fiscal authority, formed since 2010 to discuss systemic risk

issues and decide on measures to address such risks, including those emanating from entities outside

of the regulatory purview of BNM, has expanded its permanent membership to include the Securities

Commission. With regard to the FSAP recommendation for improvement in granular data on

household assets and liabilities, the authorities expect to complete collection of data by income group

by end-2014.

24. Staff position. In staff’s view, the following areas warrant attention:

Household debt. Concerns have centered on rapidly growing household debt of 83 percent of

GDP, amid rising exposure of banks to the household sector (47 percent of banks’ assets), vigorous

house price appreciation, and strong growth in unsecured consumer credit (see Box 4).

19

Given the

rapid credit growth to households and growing credit intermediation by nonbanks to households,

staff suggested that additional macroprudential measures may be needed and emphasized the

importance of continuing to enhance monitoring. Options for additional macroprudential policies

include explicit limits on debt service-to-income ratios, which would have to be supported by

ongoing development of credit registries; capping LTVs on second and first mortgages, or

additional capital charges on loans with high LTVs.

20

Recent independent policy actions by state

governments to curb price increases also suggest there is scope for closer coordination between

local and federal authorities to ensure that combined measures are not overly restrictive. Staff

welcomed progress with the collection of

granular data to support surveillance and steps

recently taken by the authorities to issue

guidelines for responsible financing to nonbanks

that are similar to those applicable to banks.

Banks’ exposure to real estate. Banks carry

significant exposure to the nonfinancial

corporate sector (43 percent of banks’ assets).

Exposure to the real estate sector makes up

about 30 percent of the total stock of corporate

loans, and nearly 40 percent of recent flow,

which suggests that a price correction in the real estate market could have a significant

19

In November 2013, S&P downgraded its rating outlook for one large bank and two mid-tier banks on concerns that

asset quality could deteriorate in the future due to rising household indebtedness and potential for a correction in

house prices. However, also during November 2013, Moodys’ affirmed its stable ratings for 9 Malaysian banks, including

the one large bank downgraded by S&P, while raising its future outlook to positive from stable.

20

In its guidelines on responsible financing for financial institutions, the BNM already requires banks to set a prudent

limit on the debt service ratio (DSR). Importantly, there is no set limit for all borrowers but rather banks are expected to

vary the DSR based on borrower creditworthiness.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

impact on the value of banks’ collateral. The aggregate nonfinancial corporate sector has assets

estimated to be more than 4 times GDP.

Corporate debt. Corporates rely mainly on bank loans for financing, which make up nearly

60 percent of total liabilities. Debt issuance is long term in nature and mainly denominated in

ringgit, averaging almost 80 percent of the total in recent years. Following the advent of the

global financial crisis in 2008, there was a surge in U.S. dollar-denominated debt issuance by

Malaysian corporates seeking to take advantage of low borrowing rates in global markets, but

this has reverted to the average pre-crisis level since 2010. The aggregate solvency situation

appears comfortable with earnings of nearly four times interest expense on debt liabilities, while

the liquidity situation with current assets of nearly 1.6 times current liabilities is adequate. In

aggregate, cash buffers estimated at 14 percent of assets are reasonable, and leverage is

moderate with a debt-equity ratio of about 45 percent. Nevertheless, the solvency situation

varies considerably across the corporate universe and the aggregate picture could change

rapidly as earnings are volatile.

21

Resident companies including large multinational companies

hedge their foreign currency exposure either with onshore banks or by relying on foreign

currency earnings from abroad to meet the foreign currency commitment.

22

There were no

reports of concerns in the corporate sector from the depreciation of the ringgit during the

summer of 2013.

Asset quality. Overall asset quality has

improved significantly in recent years with

nonperforming loans at a relatively low level

of 2 percent of gross loans in 2013 compared

with 6 percent at end-2007. Against a

backdrop of strong credit growth, the long

term improvement in asset quality is

confirmed by a trend decline in the amounts

of impaired loans, although there has been a

slight reversal in this trend since March 2013.

Providing a cushion, banks’ provisions cover

nearly 100 percent of all impaired loans.

Banks’ holdings of government and corporate securities comprised about 16 percent of total

assets in August 2013, of which federal government securities are 4.5 percent, although

accounting for government-guaranteed securities increases the potential exposure.

Nevertheless, with many of these securities held to maturity, there was no significant impact on

banks’ capital from higher MGS yields in 2013.

21

Unlike the household sector, data on individually listed corporates is available on filings data and it is therefore

possible to assess potential vulnerabilities at a granular level.

22

Further detailed assessment of foreign currency assets and liabilities of domestic corporates is desirable. It would

require access to banks’ data on the size and nature of foreign currency hedging done by corporates as this is not

publicly available information.

MALAYSIA

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Foreign currency and cross-border exposures. For the banking system as a whole, foreign

currency exposure is 4 percent of loans and 5 percent of deposits. The authorities’ own stress

tests indicate a manageable level of FX liquidity risk in the banking system. Banks emphasize the

need to strengthen fee-based income and to continue with plans to expand overseas in ASEAN.

As cross-border banking activity continues to grow, the authorities are appropriately expanding

the list of countries with which they have Memoranda of Understanding for cross-border

supervision. At present, cross-border assets are mainly funded from host countries. Overseas

lending by the top five banks makes up nearly 24 percent of total lending while loans-to-local

deposit ratios are moderate at about 84 percent. Most of the exposure and international

earnings contributions come from Singapore, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Thailand and Cambodia.

Although Malaysian banking operations in Indonesia and Thailand remain profitable as of

Q3:2013, asset quality could weaken in response to recent developments. Malaysian banks are

likely to continue expanding abroad as ASEAN economic integration picks up steam in the years

ahead. International experience suggests that substantial financial integration spearheaded by

rapid bank expansion in new markets can pose challenges for bank risk management and

supervisory monitoring. Going forward, it will thus be important to deepen home-host

cooperation and supervision and strengthen crisis prevention and mitigation mechanisms, as

outlined in Malaysia’s Financial Sector Blueprint.

25. The impact of higher interest rates. In view of ongoing and prospective unwinding of

UMPs in AEs and the normalization of global interest rates, staff conducted a simple solvency

sensitivity analysis of the aggregate household, corporate and banking balance sheets to increases

in MGS yields, the OPR, banks’ deposits rates and nonperforming loans (NPLs) (see Appendix 7).

From a financial stability perspective, plausible increases in domestic interest rates resulting from

orderly tapering of UMP in advanced economies appear manageable at the aggregate level. For

example, an increase in MGS yields by 100 bps combined with an increase in the OPR of 50 bps over

the course of one year is estimated to have little impact on aggregate household balance sheets or

bank capital because of earnings and savings buffers. However, the corporate interest servicing ratio

rises by 2.6 percentage points to 27.6 percent, which could potentially lead to difficulties at some

individual corporates but is unlikely to have a systemic impact.

26. More stringent stress tests. While an increase in borrowing costs by 100 bps over

12 months is plausible, more stringent tightening of financial conditions cannot be ruled out going

forward. A 200 bps increase in the policy rate over a one-year period would:

Increase the aggregate household debt servicing ratio (DSR) by 4 percentage points to nearly

48 percent ignoring the corresponding increase in income from savings; including the latter

would raise the aggregate household DSR by only half a percentage point. However, the asset

and liability positions may not match across all categories of households and some income

groups may experience larger increases in their DSR and may become stressed.

Raise the corporate interest service ratio by nearly 8 percentage points to 33 percent, assuming

no change in corporate earnings and full rollover of debt coming due.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

Reduce the banking system’s Tier 1 capital ratio by 1.1 percentage points to 12.8 percent (same

as a doubling of NPLs).

The same rate shock over a 2 year period would have a much lower impact on bank capital as it

would allow use of additional earnings as a buffer. It is important to emphasize that these results are

obtained at the aggregate level; and the future availability of granular data on households together

with more detailed analysis at individual corporate and banking level would provide more

information on vulnerabilities of individual institutions.

27. Authorities’ views. The authorities agreed with staff’s assessment that the financial sector is

well-diversified; and the banking system is strongly capitalized, very liquid and reasonably profitable.

They noted recent enhancements in internal models used to stress-test banks’ solvency and

liquidity, addressing, for instance, the FSAP recommendation for multiyear bottom-up analysis. In

terms of asset quality, the authorities commented that while the household debt burden has risen as

a proportion of GDP in recent years, it remains well-supported by much larger financial asset buffers;

while on the corporate side, leverage remains moderate. They described their approach to

macroprudential policies as intentionally gradual in order to avoid unintended consequences and

over-adjustment. They noted that rapidly increasing house prices are a concern but argued the

increase is not solely driven by credit but primarily reflects mismatches between supply and

demand, motivating increases in the Real Property Gains Tax (RPGT) and other budgetary measures

to increase the supply of affordable housing. With regards to the impact of UMP withdrawal, the

authorities believe that households will remain largely unaffected as potentially higher debt

servicing costs would be offset by higher rates of return on savings including deposits. The

authorities highlighted steps taken in strengthening regulation of the financial sector, in particular,

the implementation of the Financial Services Act and the Islamic Financial Services Act, which

significantly expand the scope of BNM’s supervisory and regulatory powers. In particular, the power

in relation to consolidated supervision allows BNM to extend the perimeter of its regulation and

supervision to the subsidiaries of domestic banks operating in the Labuan International Business and

Financial Center. The authorities pointed out the challenges faced by domestic banks in meeting the

Basel III LCR requirement related to the Basel III standardized assumptions regarding run-off rates

for deposits in comparison to BNM’s behavioral modeling approach. Separately, the authorities have

been monitoring closely the growth in credit provided by nonbanks to households and have taken

steps to collaborate with the relevant regulator in issuing guidelines for responsible lending.

MALAYSIA

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

CAPITAL OUTFLOWS: VULNERABILITIES AND

RESILIENCE

28. Background. Like other EMEs, Malaysia was affected by capital flow volatility in May-June

2013 and in early 2014. During May through

end-July, foreign investors reduced their

exposures to Malaysian bonds and equities (by

3.5 percent and 1.3 percent, respectively, of early-

May allocations on a net basis). Over this period,

the yield curve for government securities

steepened, with 10year yields rising by 102 bps

peak-trough, while U.S. 10-year treasury yields

rose 69 bps. Malaysian corporate bonds sold off

during the summer turbulence with yields

increasing by 120 bps (JP Morgan JACI Malaysia).

On the equity side, there was no pronounced

impact despite some foreign investor outflow, as domestic investors stepped in with purchases and

stock prices rose by 1.3 percent between mid-May and end-July. The ringgit weakened by about

11 percent against the dollar (peak-to-trough).

29. Vulnerabilities and resilience. The spring-summer 2013 episode is the latest in a series of

risk on/risk off cycles that Malaysia has endured in recent years, resulting in significant volatility in

net portfolio flows (Figure 5). With UMP withdrawal and the normalization of interest rates in AEs,

the carry trade advantage for Malaysian assets, especially government securities, will likely become

less pronounced. While the mission’s baseline assumption is that UMP exit is likely to be gradual,

the possibility of sudden and significant portfolio outflows from Malaysia and other emerging

market countries cannot be ruled out. Malaysia’s vulnerability is related to its relatively high level of

federal debt and large foreign holdings of government securities (42 percent). These risks were

traditionally mitigated by Malaysia’s strong external position but have come to the fore recently,

following the decline in its current account surplus (to 3−4 percent of GDP in 2013−14 from an

average of 12½ percent of GDP in 2009−11). But, similar to its experience during bouts of volatility

in global capital flows in recent years, Malaysia dealt with the latest episode skillfully, allowing the

exchange rate to act as a shock absorber while intervening to avoid excessive volatility.

30. The role of domestic institutional investors. The Malaysian economy’s resilience during

the May-June episode was facilitated by offsetting opportunistic purchases by large domestic

institutional investors who provided depth to its financial markets. Staff confirmed that domestic

investors, including banks and saving funds, resorted to significant purchases of equities as well as

domestic government securities during the turbulent period, thus facilitating “financial” (as opposed

to “real”) adjustment (See Appendix 8 and WEO, October 2013, Chapter 3). Domestic investors play a

stabilizing role in the market: if foreign investors were to reduce holdings of domestic assets sharply,

the resulting depreciation of the ringgit would make sales of foreign assets by domestic investors

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

1234123412341234123

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

EPF Foreign Banks

Malaysia: Federal Domestic Debt by Holder

(In billions of ringgit)

Sources: Bank Negara Malaysia; staff calculations

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

more attractive prompting an offsetting inflow. Staff’s illustrative calculations using data for the third

quarter of 2013 suggest domestic investors have additional capacity of about 6 percent of GDP for

purchases of MGS. By comparison, foreign outflows from MGS during Q2:2013 amounted to about

1 percent of GDP, and foreign investors held about 13 percent of GDP in MGS as of Q3:2013.

Nevertheless, caution is warranted: international exposure of domestic institutional investors,

estimated at about 20 percent of GDP, is well below that of total foreign ownership of domestic

equities and bonds; and, overseas holdings of domestic institutional investors may not be fully

liquid.

31. Authorities’ views. The authorities highlighted the growing depth of domestic capital

markets, which has led to a structural increase in nonresident holdings of government and BNM

securities. They noted that compared with past episodes of capital flight, Malaysia is now better

prepared to deal with potential risks of capital outflows on account of higher levels of international

reserves, better capitalized financial intermediaries, a wider range of monetary instruments to

manage liquidity, and much deeper capacity of domestic institutional investors to absorb selling by

nonresidents. The authorities also observed that the volatility in capital flows experienced during

May-September 2013 did not have any significant adverse impact on the real economy.

Estimated Capacity for Additional Holdings of Malaysian Government Securities Domestically

Assets Estimated Target Q3:2013 MGS Space in MGS Space Total

Entity (In percent MGS Allocation Underweight Stock of Assets in Flow MGS Capacity

of GDP)

EPF--Domestic Pension Fund 52.9 30.0 2.0 1.1 0.5 1.5

KWAP--Civil Service Employees Pension 10.1 25.0 3.0 0.3 0.1 0.4

LTH--Haj Support Fund 4.9 28.0 3.0 0.1 0.1 0.2

Khazanah 12.2 -- -- -- -- --

PNB--Permodalan National Berhad 25.7---- ------

Banks 205.9 5.0 0.5 3.1 0.5 3.6

Total 311.8 1.5 0.6 5.8

Total stock of MGS 51.6

Foreign holdings of MGS 13.2

MGS outflow (June-September) 1.0

Sources: Bank Negara Malaysia; GLICs; and IMF staff estimates (December 2013).

(In percent of GDP)(In percent)

MALAYSIA

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

EXTERNAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS

32. Background. In recent years, the Malaysian economy has undergone significant external

rebalancing, reflecting robust domestic demand (including from large investment projects under the

government’s Economic Transformation Program (ETP)) and weak external demand. This has led to a

dramatic narrowing in the external current account surplus, which declined to 3.8 percent of GDP

in 2013, from 6.1 percent of GDP in 2012 and 11.6 percent in 2011, while the nonoil current account

balance has swung into a deficit of about 2.4 percent of GDP from 4.2 percent surplus for 2011.

From a savings-investment perspective, about two thirds of the adjustment was due to a strong

surge in private investment and the large investment projects under the ETP, which bodes well for

the medium term growth outlook. Over the past year, the exchange rate has fluctuated more widely

than in 2010−2012, but around a fairly horizontal trend. International reserves have decreased

slightly and the IMF’s composite reserve adequacy metric stands at a comfortable 117 percent. The

net international investment position was a small positive in 2011 but has turned negative and now

stands at –2 percent of GDP.

33. Outlook and Assessment. Looking ahead, over the medium term, increased public sector

savings will be offset by sustained private consumption and investment activity and is expected to

result in a current account surplus of 3−4 percent over the medium term.

23

The significant reduction

in Malaysia’s current account surplus is reflected in a commensurate narrowing of Malaysia’s

estimated external imbalances or gaps (see Appendix 3). Staff views any remaining current account

and real exchange rate gaps as reflecting inadequate social protection (beyond that captured by

public health expenditure), the need to improve the risk sharing characteristics of the pension

system, investment bottlenecks, infrastructure

gaps, labor force skill mismatches, and rigidities in

the labor market. Staff’s estimate of the cyclically-

adjusted current account norm for 2013 is

1.5 percent of GDP, compared to the External

Balance Assessment’s (EBA) norm of -0.1 percent.

With a projected cyclically adjusted current

account surplus of 4.1 percent of GDP, this

implies a total current account gap of 2.6 percent

of GDP, with the policy gap contributing to the

bulk. Malaysia’s real effective exchange rate

(REER) is assessed as moderately undervalued by about 9 percent, reflecting savings and investment

gaps and consistent with the identified current account gap, with the estimate subject to

considerable uncertainty.

23

Staff estimates indicate that every 1 percentage point improvement in the fiscal balance could strengthen the

current account by about 0.4 percentage point.

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

34. Policies. Structural reforms aimed at strengthening social protection while safeguarding

fiscal sustainability, together with improvements in the investment climate, and population aging

should help reduce the saving-investment gap over time. However, these changes take time as they

involve the creation and reform of institutions.

Staff recommended the introduction of unemployment insurance, which the authorities are

studying, and which would further strengthen the safety net and reduce precautionary savings.

Staff also noted that there is scope to improve the coverage and adequacy of retirement

schemes in the private sector in order to provide more effective protection against poverty in

old age.

These measures should be complemented by continued exchange rate flexibility with

intervention limited to dampening excessive volatility, which will likely be associated with a

gradual appreciation of the real exchange rate over time and support external rebalancing.

35. Authorities’ views. The authorities agreed with staff that the current account will remain in

small surplus for the foreseeable future; however, they disagreed with staff’s assessment of external

imbalances, particularly the exchange rate. They questioned the validity of the EBA exercise for

Malaysia where there are large unexplained residuals and argued that EBA’s cross-country approach

may not fully capture Malaysia's unique characteristics. The authorities questioned the assessment

of the exchange rate as undervalued in view of the selloff of the ringgit during periods of financial

turbulence. They emphasized that they do not manage the level of the exchange rate but intervene

only to smooth excessive volatility. In addition, the authorities questioned the staff’s assessment that

the current account surplus is too large in view of the sensitivity of the global financial markets to

current account deficits in emerging market economies, as reflected in the vulnerability of deficit

countries to capital outflows during crisis periods.

BOOSTING GROWTH AND INCLUSION: THE ROLE OF

HUMAN CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT

36. Background. Malaysia is implementing an extensive agenda of structural reforms aimed at

strengthening growth and making it more broadly shared, as elaborated in a number of multiyear

transformation programs to upgrade human capital, foster technological readiness, inject greater

competition in product markets, and strengthen the government’s performance (Appendix 9). In this

connection, and in the face of heightened international demand (and competition) for talents,

efforts to strengthen Malaysia’s education system have acquired heightened importance. Malaysia

has made important progress in raising school enrollments: secondary net enrollment has risen

sharply, as has enrollment in tertiary education. But Malaysia still faces shortages of high-skill

workers, and skill mismatches are an important constraint in efforts to raise potential growth and

reduce income inequality.

MALAYSIA

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

37. Policies. While Malaysia has achieved much in this area, additional reforms are needed to

make the education system more efficient and cost effective.

The authorities have created an array of initiatives but, in the context of scarce resources, some

deliberate prioritization is needed. Priorities should include expanding access to tertiary

education and increasing availability of financing to underserved groups.

Quality control in private universities and retaining Malaysian-grown talent in the domestic

economy are also important (World Bank, 2012).

More work is needed to improve educational attainment (what students actually know) at the

basic and secondary level. In this regard, staff welcomes the authorities’ goal to place Malaysian

students in the top third of international assessments and to reform and improve the

performance of the Ministry of Education (see Malaysian Education Blueprint 2013−25).

38. Authorities’ views. The authorities stressed that their ambitious transformation programs

and blueprints are helping them achieve their goal of transforming Malaysia into an advanced,

high-income nation by 2020. They pointed out that they are engaged in a multifaceted effort to

improve skills, including through partnerships between businesses and higher education catalyzed

by government funding. They recently merged the Ministry of Higher Education into the Ministry of

Education and expect the requirement of greater accountability from teachers and researchers to

result in improved results in teaching and academic research. They are also intensifying human

capital development efforts in the elementary and secondary education with a view to bring

Malaysian students to the top one third of countries tracked by the Program for International

Student Assessment (PISA). Progress in improving educational attainment, as outlined in the

Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2013−2025, is a high priority for them. They agreed with the call for

achieving better performance in education in a tighter budgetary environment.

STAFF APPRAISAL

39. Outlook. The Malaysian economy’s near-term growth prospects are favorable, and the

transition to the post-UMP environment should be relatively smooth: real GDP growth picked up in

the second half of 2013 and this momentum is likely to be sustained in 2014. Continued robust

domestic demand, together with an improved external environment, should offset mild headwinds

from the timely, decisive, yet gradual fiscal consolidation. Underlying inflationary pressures remain

subdued, but headline inflation has picked up somewhat reflecting the effects of subsidy

rationalization.

40. Risks. Downside risks to growth include a bumpy exit from UMP, which could be associated

with a protracted period of economic and financial volatility in EMEs. However, Malaysia’s current

account should remain comfortably in surplus, and its financial system is deep and has

demonstrated its capacity to withstand such volatility and contain the impact on the real economy.

A flexible exchange rate regime combined with credible monetary policy have put Malaysia in a

MALAYSIA

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25