Center for Municipal Finance

1155 East 60th Street

Chicago IL 60637

T 773.834.1468

The Impact of Property Tax Appeals on Vertical

Equity in Cook County, IL

Robert Ross

June, 2017

0

This paper began in a practicum lead by Professor Chris Berry during the fall of 2016. Chicago Tribune Reporter Jason Grotto

helped obtain the public records necessary for this analysis. Thanks also to the students who participated in the practicum organising

data and producing preliminary results: Sarah Guminski, Michael Harvey, Dani Litovsky Alcala, Megan Maxwell, Hector Salvador

Lopez, Alex Sarabia, Daniel Truesdale, and Alvaro Valdes Mena.

Abstract

Cook County has one of the highest rates of property tax appeals in the

country. Do appeals make property taxes more fair and accurate? Using

administrative property tax data from for 2003-2015, I quantify the level

of regressiveness in property taxes. I find property taxes to be highly

regressive. I then investigate whether the appeals process mitigates or

exacerbates regressiveness. I find that post-appeal assessment ratios are

more regressive than pre-appeal ratios, providing evidence that the prop-

erty tax appeal process decreases vertical equity. I further find that ef-

fective tax rates are higher in neighborhoods with a higher percentage of

minorities, and lower in wealthier and better educated neighborhoods.

1 Introduction

In his survey of taxation during the first 100 years of

American independence, Richard T. Ely wrote:

The fundamental idea of our tax systems is

a democratic one. It is... that men are

bound to serve the state in the degree in

which they have the ability to serve them-

selves. The reasons why these earliest meth-

ods [of assessment] were abandoned are suf-

ficiently evident... When one acre of land

was often worth ten or twenty times, or even

fifty times, as much as another situated in

the same commonwealth, there could not

fail to arise a demand for a system of tax-

ation which would adjust the burdens of the

government more accurately and make them

bear upon each individual more nearly in

proportion to his ability.

1

Property tax assessment is a politically contentious

exercise. As assets have become more complex and less

visible, estimating an individual’s “capacity to serve her-

self” has become highly technical and difficult. Modern

systems of property tax assessment evolved out of a se-

ries of technical and legal innovations to become quasi-

judicial apparatus with both administrative and legal

levels of review. Local governments nevertheless con-

tinue to rely heavily on property taxes, and fairness in

taxation is important to the political and economic sta-

bility of those governments. However, while economists

are generally in favor of property taxes, the public’s

mind is well set against them; the property tax is re-

garded as the “least fair” tax by the average American.

2

The greater the perception that property taxes are

unfair, the more likely taxpayers are to appeal their

taxes. Indeed, property tax appeals are becoming more

numerous nationwide.

3

Cook County, IL (the County),

enthusiastically follows this trend. In 2015, about 20

percent of residential taxpayers filed more than 360,000

appeals. Figure 3 shows statistics for appeals between

2003 and 2015. Over that period, the number of appeals

increased by about 20% with every reassessment cycle,

as has the percentage of appeals resulting in a reduction

in taxable value.

The increase in appeals has been actively encour-

aged by various County officials and offices. County of-

ficials actively encourage taxpayers to appeal their prop-

erty tax assessments, and the County Board of Review

(BOR) trains elected officials, including Chicago legisla-

tors, to help constituents appeal their taxes. In addition,

the County recently instituted a new online property tax

appeal system which allows property owners to easily ap-

peal their own taxes without legal representation. These

features of the County’s property tax system result in a

very large number of appeals. Do the large and growing

number of property tax appeals encourage fairness and

accuracy in Cook County’s property tax system?

The focus of this paper is the impact of the prop-

erty tax assessment system, and property tax appeals

in particular, on vertical equity in property taxation.

I investigate the prima facia case for vertical equity

in assessment ratios, property taxes, and tax appeals.

The assessment ratio of a property is the ratio of the

Cook County Assessors’ Office’s (CCAO) estimate of

that property’s market value to the actual sale price of

the property, in the year the property sold.

4

The effec-

tive tax rate on housing wealth is the ratio of taxes paid

in the year a property sold to the sale price of that prop-

erty, in the year the property sold. If effective tax rates

are strongly negatively correlated with home values, I

take this as evidence of regressive property taxes.

Using administrative data from the Cook County As-

sessors’ Office (CCAO), I find that property taxes in

Cook County became extremely regressive following the

collapse of the housing bubble in 2008. Figure 4 shows

the depressive effect of the housing bubble on sales vol-

umes and median home prices in the County. Figure 7

displays effective property tax rates by home value for

the period following the housing bubble. That figure

clearly shows a strong negative relationship between ef-

fective tax rates and property values. This is prima faci

evidence of regressiveness in property taxes.

I also find that appeals make taxes more regressive.

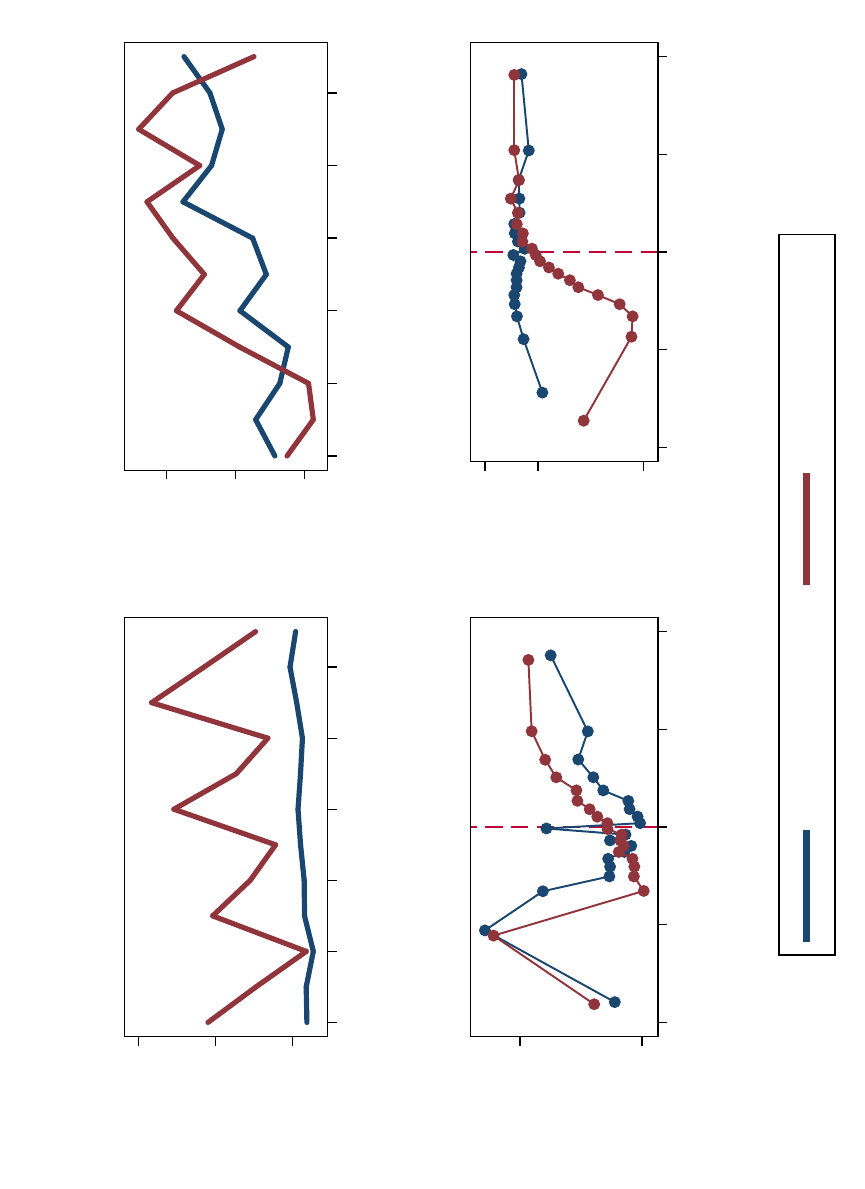

Figure 1 shows the change in assessment ratios for all

properties for the period 2009-2015. Though appeals

reduces taxable values, on average, across the range of

home values, they tend to decrease them more for more

valuable properties. The appeals process as a whole de-

creases vertical equity by granting proportionately larger

reductions in value to more valuable properties.

Property assessment is a complex, constantly evolv-

ing field. While the data for this analysis comes from

Cook County, IL, I do not believe the County is unique

in terms of veritcal equity or property tax appeals. This

analysis suggests a number of policy changes to encour-

1

Ely (1888),[8] p. 131

2

Gallup (2005)[11]. Also see Chapter 11 of Fisher (1996)[9].

3

Doerner and Ihlanfeldt (2012)[7].

4

For simplicity, I calculate the assessment ratio as 10*(assessed value)/(market value), so that an assessment ratio of 1 means that

the assessor has perfectly predicted a property’s value.

1

age more equity in the property tax system. Lessons

learned in the revision and execution of assessment prac-

tices in the County can be duplicated by other counties

nationwide.

2 The “least bad” tax

The property tax as administered in the United States

is a paradox: on the one hand, voters regularly report

that they believe they get the “best bang for the buck”

from property taxes,

5

local governments rely heavily on

property taxes to finance local services,

6

and economists

credit the property tax with a number of positive at-

tributes. On the other hand, voters regularly report that

the property tax is the “most unfair,” “worst” tax ac-

cording to repeated opinion surveys,

7

there are frequent

property tax revolts and other initiatives to limit prop-

erty taxation, and property tax revenues as a share of

GDP are declining in the US even while other tax rev-

enues are increasing. Indeed, the property tax revolts of

the late 1970s were defining events in the political econ-

omy and local public finance of the United States, and

yet there is no consensus to date on the causes of these

revolts.

8

Canonical public finance textbooks take an opti-

mistic view of the property tax with respect to vertical

equity. Fisher (2007) sums up a discussion of the eco-

nomic effects of the property tax writing “these factors

combined do not support a conclusion of general prop-

erty tax regressivity.”

9

Rosen (2002) argues that the

property tax is broadly hated because it is perceived as

being regressive. This perception he attributes to the

dominance of the “traditional view” of property taxes

as excise taxes on a bundle of land and capital, and the

disjoint between housing wealth and liquidy assets for

some subgroups of taxpayers.

10

He equivocates as to

whether the tax is, in fact, regressive.

Other economists have argued as well that the prop-

erty tax is theoretically progressive.[30] In an environ-

ment where the Tiebout Hypothesis holds, property

taxes are fully capitalized into home values and behaves

like a user fee rather than a tax. In such an environment,

Rosen (2002) writes that “the notion of progressiveness

is meaningless.” It is unclear, however, whether ver-

tically inequitable property taxes might still behave as

use taxes; do lower income residents derive greater pro-

portional benefits from local government than wealthier

residents? Most recently, Youngman (2016)[29] writes

“The easy use of the term regressive to describe the prop-

erty tax in popular debate is not justified on economic

grounds,” arguing that the ambiguity of the incidence of

the property tax makes it difficult to ascertain its true

regressiveness.

Most of the aforementioned work deals with the inci-

dence of a uniform tax on real estate. Recent empirical

research, on the other hand, has focused more on the ad-

ministration of the property tax. In that body of work,

there is an emerging consensus that property taxes are

administer in such a way as to be regressive on their

face. This seems particularly true when conditions for

property appraisal are unfavorable, like the period af-

ter a major real estate bubble. Suits (1977)[25], Phares

(1980)[20], Metcalf (1994)[18], and Plummer (2003)[21]

use different approximations of income to compute a

suites index and determine whether property taxes are

regressive.

11

In these studies, estimated Suites Indices

range from .23 (fairly progressive) to -.13 (a bit regres-

sive). More recently, Cornia and Slade (2006)[6] and

McMillen and Weber (2008)[17] find that property taxes

are regressive in Cook County specifically, although their

data are limited in size and cover periods from before the

collapse of the housing bubble.

McMillen (2011)[15], Hodge et. al. (2016)[12], and

Krupa (2012)[14] find that post-housing bubble assess-

ments became highly regressive in Cook County, Detroit,

and Indiana respectively. McMillen (2013)[16] exam-

ines the impact of property tax appeals in Chicago in

2006, finding that they decrease vertical equity slightly.

Doerner and Ihlandfeldt (2012) [7] examine the effect

of appeals on assessment ratios in Miami-Dade County

and find that they disproportionately benefit white, rich

neighborhoods. This paper most resembles these papers

in scope, methods, and focus.

5

Cabral and Hoxby (2012)[5]

6

Anderson and Ross (2013)[3]

7

Gallup (2005)[11]

8

Anderson and Pape (2011)[2]

9

Fisher (2007)[10], p. 370

10

Rosen (2002)[22], p. 494

11

The Suites Index was proposed by Suites (1977)[25] as a standard measure of verhtical equity in taxation. I calcualte the index in

Appendix B. For a good description of the Suites Index, and a bootstrapping method for hypothesis testing, see Anderson (2003)[1].

For a summary of recent empirical work on progressivness in property taxes, see Stanahan et. al. (2014)[26]. The suites index follows

the logic of the Gini Coefficient calculated from the Lorenze Curve. To calculate the Suites Index, plot the cumulative tax payments

against the cumulative wealth of a population, and calculate one minus the ratio of the area under this curve to the area under a 45

degree line. Like the Gini Coefficient, the resulting index shows the degree to which taxpayers at lower levels of wealth bear larger

proportions of the total tax burden.

2

This paper contributes to the literature on local

property taxes in a number of ways. First, I document

the prima facia regressiveness of the property tax sys-

tem in the second most populous county in the US using

a straightforward approach: effective tax rates. This is

the only study I am aware of to clearly show how regres-

sive assessments and appeals lead to regressive taxes. I

use a very large administrative dataset covering a large

period of time to show patterns of assessment and tax-

ation across realized property values and neighborhood

demographic attributes. The only other studies I am

aware of to use such a large dataset for this purpose is

Krupa (2012)[14] and Doerner and Ihlandfeldt (2012)[7].

This paper builds on their analysis by offering novel, and

simpler ways of measuring regressiveness, and by exam-

ining the period before, during, and after a large hous-

ing bubble. This informs our understanding of how the

County’s property tax performs under conditions which

are unfavorable to predicting property real estate values,

and whether the appeals process sufficiently corrects for

errors in assessed values during a housing bubble. My

findings add to a growing body of literature which sug-

gests that the property tax is regressive in practice be-

cause assessments are regressive.

3 Data and calculations

The data for this analysis comes from administrative

records of the CCAO, the Cook County Treasurer’s Of-

fice, the City of Chicago, and the US Census Bureau,

and includes more than 1.5 million residential properties’

taxes, assessed values, sales, appeals, and other infor-

mation used for property tax purposes from 2003-2015.

Unique Property Identification Numbers were matched

with the Census Tracts which contained them. This

allows me to identify correlations between census-tract

level characteristics with tract-level property taxes. My

final dataset contains 21.4 million observations of resi-

dential properties’ administrative property tax records

from 2003-2015.

I selected properties which sold between 2003-2015.

Consistent with standard assessment practices, I take

the sale price of a home as the realized value in the

year the home sold. My dataset of residential sales con-

tains just less than 600,000 residential home and condo-

minium sales from 2003-2015.

12

Annual sales volumes

and median prices are reported in Figure 4.

This study considers three phases in the property tax

assessment process. The first step in the assessment pro-

cess is a “first-pass” made be the CCAO. In this step, the

CCAO notifies taxpayers of their preliminary assessed

values. These assessed values mostly determine a tax-

payers’ property taxes for the next three years. After

being notified, taxpayers may appeal their assessments

through both the CCAO and the BOR, and then in court

following these agencies determinations. Following the

resolution of all appeals, a final assessed values is as-

signed to each property. Finally, taxes are calculated

based on that final assessed value, exemptions, and the

applicable tax rates. This paper focuses on the bench-

marks of this process: first-pass assessments, final as-

sessments, and taxes.

To measure regressiveness, I rely on the standard

measure used in ratio studies: Price Related Differen-

tial (PRD).

13

In Appendix B, I also calculate two other

measures of vertical equity. These other statistics are

consistent with the patterns shown by the PRD.

The PRD is given as the ratio of un-weighted mean

assessment ratios to weighted mean ratios in a given time

period:

P RD =

P

n

j=1

E

CCAO

[V

j

]/V

j

/N

P

N

j=1

w

j

∗ E

CCAO

[V

j

]/V

j

/N

(1)

where property values are used as weights. If the

weighted mean is equal to the unweighted mean, as-

sessments are perfectly uniform across home values and

the PRD will equal 1. If the weighted mean is rela-

tively smaller than the unweighted mean, higher value

properties are assessed at lower rations, and the PRD is

greater than 1. PRD is negatively associated with re-

gressiveness. The standard “acceptable” range for PRD

is [0.97, 1.02]. This range is asymmetric around 1 be-

cause there is an upward bias in the denominator which

does not effect the numerator.

14

The variance of this

statistic is not well defined, so I use bootstrapping to

obtain an estimate of the variance.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Vertical equity in assessments

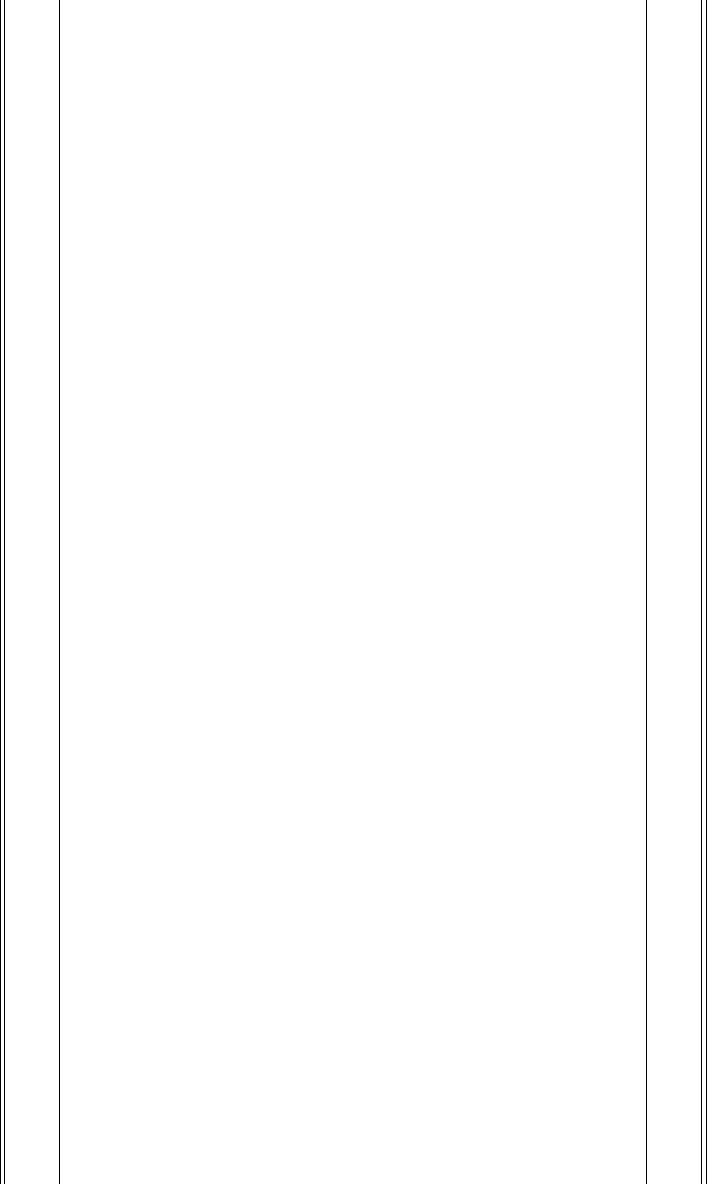

Table 1 and figure 5 show PRD before and after appeals.

Figure 2 plots the change in the PRD by major property

type, with bootstrapped margins of error. And figure 1

shows the change in assessment ratios by home value for

all County properties 2009-2015.

12

I dropped 68 observations where the appeals process actually increased properties’ taxable values. The omission of these observa-

tions has no qualitative effect on my results, but their inclusion causes my graphs to display oddly because the amount of increase was

extreamly large for these observations.

13

IIAO Standard for Ratio Studies, 2013, p. 17

14

IIAO (2013)[13], p. 35

3

Figure 1: Impact of appeals on assessment ratios by home value

.6 .8 1 1.2 1.4

Ratio of assessments

to sale price

$250K $500K $1 mln $1.3 mln

Sale value

Assessment ratios

−6% −5% −4% −3%

Effect of appeals on

assessment ratio

$250K $500K $1 mln $1.3 mln

Sale value

Difference in pre− and

post− assessment ratios

Cook County 2009−2015

Pre−appeal Post−appeal

Together, these figures demonstrate that property

tax assessments in the County are regressive, and are

made more so by appeals. Looking at homes in the 25th

and 75th percentiles of sale price 2009-2015, homes in

the lower quartile are assessed during the CCAO’s first-

pass at ratios 23% higher than those in the upper quar-

tile. At the end of the appeals process, homes in the

lower quartile are assessed at a rate 24% higher than

homes in the higher quartile. That is so because ap-

peals lower taxable value proportionally more at higher

home values. Assessment ratios are 3.3% less after ap-

peals for the 25th percentile, and 4.1% less for the 75th

percentile. Overall, appeals make property tax assess-

ments more regressive by granting larger reductions at

higher market values.

The CCAO & BOR introduce regressiveness into the

property tax system in the way they grant appeals. The

CCAO & BOR often grant reductions in assessed value

to properties which are already under-assessed. More

than half of under-assessed properties sold 2009-2015

filed an appeal, and the CCAO & BOR granted 22%

of those appealing properties some reduction in their

assessed values. On average, the CCAO & BOR re-

duced assessed values for already under-assessed prop-

erties which appealed by $5,700, or 23% of the average

assessed value for appealing under-assessed properties.

By comparison, over-assessed properties saw an aver-

age reduction of $8,169, 28% of average assessed values.

Simple regressions of the probability of winning an ap-

peal, and the percentage reduction in assessed value on

first-pass assessments shows very little correlation be-

tween winning appeals and first-pass assessment ratios.

Taxpayers are more likely to appeal their assess-

ments if they are over-assessed, and if their homes are

worth more. Even after accounting for these factors,

however, neighborhood demographic characteristics are

still significantly correlated with assessment ratios, ap-

peals, and effective tax rates. Table 2 shows the re-

sults of regressions on outcomes of interest. Areas with

higher levels of education, higher property values, and

fewer minorities pay significantly lower tax rates. Figure

8 shows selected correlations with demographic charac-

teristics of census tracts and mean effective tax rates.

Geographic patterns of tax appeals, assessment ratios,

effective tax rates, and home values are shown in 9 -

12. These maps convey a sense of the distribution of

property taxes to those familiar with the demographic

topography of Chicago.

Some of these correlations may be driven by the fact

that taxpayers self-select as to whether they appeal their

taxes or not. This self-selection may drive some regres-

siveness in the appeals process as well. For example,

many larger condominiums buildings hire attorneys to

file appeals for all of the units in the building, taking

4

advantage of the returns to scale in this type of appeal.

Effective tax rates may be consequently lower for larger

condominium buildings. Figure 6 shows the strong, pos-

itive relationship between condominiums’ building size

and the probability of any individual unit filing a prop-

erty tax appeal. The difference in effective tax rates be-

tween condominium properties and single-family homes

seen in figure 7 may be a product of the different rates

of appeal between these types of properties, although

assessment methods also differ between these types of

properties.

Another factor in tax appeals are attorneys: tax-

payers spent an estimated $22 million in lawyers’ fees in

2015 appealing their taxes. Tax lawyers in Cook County

solicit customers during tax season, and it may be that

those lawyers solicit more valuable property more of-

ten, since those properties are more likely to yield larger

nominal fees. Lawyers may also target English-speaking

populations, or areas with more density of sales, where

it is easier to find clients and win appeals. There may

also be other ways in which lawyers select clients which

increase regressiveness in property taxes.

Finally, there may be simple geographic informa-

tional spillovers in appeals off all residential properties,

making neighbors of taxpayers that appeal more likely

to appeal themselves. This may be because neighbors

voluntarily share tax information with each other, or be-

cause neighbors look at each others’ property tax infor-

mation online. This may result in some neighborhoods

having a very high rate of appeal, simply because of the

compounding effect.

15

4.2 Vertical equity in taxes

Regressive property tax assessments lead to regressive

property taxes. From 2009-2015, Chicago properties at

the 25th percentile of sale value were taxed at a rate 24%

higher than properties at the 75th percentile of value.

16

The 25th percentile sale values in Chicago was about

$156,000, paying an average tax of about $2,300.

The 75th percentile of sale value was nearly $370,000,

paying an average tax of $4,700. The average effective

tax rates at these quartiles were about 1.5% and 1.2%

respectively. If homes at the 25th percentile paid the

same tax rate as those at the 75th percentile, their taxes

would be about $465/year lower on average. On the

other hand, if Chicago properties in the 75th percentile

faced the average effective tax rate that properties in the

25th percentile faced, they would have paid $1,142/year

higher taxes on average.

To further contextualize these figures, I randomly se-

lected two representative properties which sold in 2011,

the year in which assessments in the County were most

regressive. I restricted my selection to owner-occupied,

single-family homes in the 25th and 75th percentiles of

property value with successful property tax appeals.

The property in the 25th percentile of home values is

in the Village of Stickney, IL, a mostly-white suburban

community bordering Chicago to the south west. Stick-

ney has a median household income of about $43,000,

and about 10% of residents are college educated. The

property in the 75th percentile of property values lies in

the North Park community of Chicago, where median

household income is about $71,000 and about 50% of

the residents hold a college degree.

The Stickney property sold in 2011 for $130,000,

and the CCAO estimated its market value at $238,660,

nearly double its actual market value. In contrast, the

North Park property sold in 2011 for $309,000, but the

CCAO estimated its market value at $281,100. Both

properties filed successful appeals in that year: the Stick-

ney won a reduction of $12,640 of taxable market value,

while the North Park won a reduction of $12,300 of tax-

able market value. The statutory property tax rates in

Stickney are nearly twice as high as they are in the City

of Chicago, a reflection in part of the lower amount of

commercial property value in that community. For a di-

rect comparison of the impact of assessments on taxes, I

apply the statutory rate in Chicago to both properties.

Under uniform tax rates, the Stickney’s property tax bill

would have been $4,300, and the North Park property’s

bill would been $5,100. If both properties had been as-

sessed perfectly, those bills would have been $2,400 and

$5,900 under uniform tax rates.

Regressiveness shifts a considerable portion of the

total property tax burden onto lower value properties.

Consider the 13,539 residential sales in the City of

Chicago in 2011. Cumulatively, the total value of those

sales was about $5.1 billion. Those properties paid $59.1

million in property taxes in that year. Those revenues

are not taken in equal proportion from every property.

The County’s property taxes were most regressive in

2011; the average effective tax rate on properties in

Chicago in the 25th percentile of property value was 30%

higher than that on properties in the 75th percentile of

property values. The nature of property taxes is such

that decreases in taxes for one group is mechanically

offset by increases in taxes for another group. Suppose

15

In Cook County, the public may look up property tax records, including taxes paid, exemptions applied, and appeal status, online.

16

Throughout this analysis, I use Chicago properties to compare effective tax rates, even though I use properties Countywide to

compare assessment ratios. This is so because all residential properties in Chicago lie in the same taxing jurisdictions, so comparisons

of effective tax rates reflect differences in the assessment process.

5

Figure 2: Impact of appeals on vertical equity

−.005 0 .005 .01 .015 .02 .025 .03 .035 .04

Change in PRD

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

year

Single−family homes

Effect of appeals on PRD

−.005 0 .005 .01 .015 .02 .025 .03 .035 .04

Change in PRD

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

year

Condominiums

Effect of appeals on PRD

2003−2015

Change in PRD

caused by appeals

Margin of error

for first−pass PRD

that the revenues from these properties was collected

uniformly according to property value, as is legally stip-

ulated: what impact would this have on tax bills?

Re-calculating each property’s tax bill by applying

the uniform rate required to raise these funds in equal

proportion from all properties, I can quantify the nomi-

nal level at which properties are over- and under-taxed.

In 2011, nearly 9,500 properties paid taxes higher than

that calculated from a uniform rate, while about 4,000

paid lower taxes.

17

Redistributing that tax burden in

equal proportion to housing wealth, I find that the av-

erage decrease in tax bills for properties paying a higher

effective tax rate is about $1,500, while the average in-

crease in tax bills for properties paying lower effective

tax rates is about $4,600. There are about 735,000 resi-

dential properties in the City of Chicago. If this sample

of about 1.8% of all properties is representative of the

general pattern of vertical inequity across the City, the

magnitude of redistribution of tax burdens from higher

to lower value homes could be as much as 50X larger.

Figure 13 graphs the results of this exercise. On the

left side of the panel, the average difference between ac-

tual taxes paid and taxes paid under a uniform tax rate

is plotted against property values. The x-axis is scaled

by value percentiles. This graph shows that more than

half of the properties in the sample would experience a

reduction in their property taxes if a uniform tax rate

was applied across home values. The right panel shows

the average effective tax rates paid at each percentile of

sale value, as well as the uniform effective tax rate re-

quired to raise an equivalent amount of revenues from

this subsample of properties. To the degree that the bias

in assessment ratios exhibited among properties which

sold is a good approximation of bias in assessment ratios

for all properties, this exercise illustrates the magnitude

of the impact of regressiveness in the County.

5 Policy recommendations

Estimating the value of real estate is a difficult and com-

plex task. Concerning California’s property tax system,

Frederick Stocker wrote

(The property tax) resembles a structure de-

signed by a mad architect, erected on a shaky

foundation by an incompetent builder, and

made worse by the well-intentioned repair

work of hordes of amateur tinkerers.

18

17

In calculating the uniform rate, I exclude properties in the top and bottom 1% of effective tax rate.

18

Stocker (1991)[27], p. 1.

6

To some degree, such can be said of any democratic in-

stitution which is the product of negotiated compromise.

With advances in computing and statistical sciences,

however, it increasingly seems as though the technical

aspects of property tax assessments are in want of re-

design. Improvements in the County’s assessments may

translate into large improvements in the administration

of the property tax nationwide.

First-pass assessments in the County need to be ac-

curate, and their errors should not be correlated with

property values. If traditional methods of estimation do

not yield such errors, the CCAO should explore non-

traditional methods. For example, the CCAO could

conduct a competition with a large cash award for the

person or group who designs a significantly better as-

sessment algorithm, similar in spirit to the famous Net-

fliz Prize. Another example might be to explore survey

methods of predicting property value. Are self-reported

property values, with some threat of audit, a more reli-

able way to estimate values? Do neighbors truthfully re-

port their neighbors’ property values? The CCAO could

investigate these and other approaches to property tax

assessment.

Transparency can help improve government services

simply by changing the political incentives faced by the

county assessor. The CCAO should make the property

tax database available, in full, to the public, along with

all computer code necessary to replicate the assessors’

estimation process. This would not only increase the

accountability of the system, but also may encourage an

entrepreneurial data scientist to suggest improvements

to the predictive models used by the CCAO.

The BOR explicitly evaluates assessments with re-

spect to uniformity, or horizontal equity. This ensures

that properties with similar characteristics are assessed

at similar levels. This does not address vertical equity

at all, as I have shown. Incorporating a systemic re-

view of assessments with respect to vertical equity into

BOR considerations might improve the end result of the

review process.

Improving the property tax assessment system in the

County is not merely a technical exercise. There is are

at least two entrenched political classes which benefit

from poor-quality assessments. From 2009-2015, tax

attorneys made an estimated $133 million in revenues

from successful tax appeals. Poor assessments create

revenues for tax attorneys, and any attempt to improve

assessment quality will likely be met by resistance from

these lawyers. In addition, most local politicians as-

sist constituents with tax appeals, in some cases hiring

staff members specifically for that purpose. This gener-

ates political capital elected officials will be reluctant to

trade for better quality assessments.

References

[1] Anderson, John E., Roy, Atrayee Ghosh, Shoe-

maker, Paul A. “Confidence Intervals for the Suites

Index.” National Tax Journal, n. 1, pt. 1, 2003.

[2] Anderson, Nathan and Andreas Pape. “A Model of

Constitutional Constraints on Benevolent Govern-

ments and a Reassessment of the 1970s Property

Tax Revolt.” Working Pape, 2011.

[3] Anderson, Nathan, and Robert Ross. “Rethinking

the Property Tax.” The Illinois Report: Institute

for Government and Public Affairs, 2013.

[4] Borg, Mary O., Stranahan, Harriet A., and William

Voorhees. “The Incidence of the Property Tax and

Property Tax Preferences.” 2014.

[5] Cabral, Marika, and Caroline Hoxby. “The Hated

Property Tax: Salience, Tax Rates, and Tax Re-

volts.” NBER Working Paper 18514. 2012.

[6] Cornia, Gary C., and Barrett A. Slade. “Horizontal

Inequity in the Property Taxation of Apartment,

Industrial, Office, and Retail Properties.” National

Tax Journal, no. 1, 2006.

[7] Doerner, William and Keith Ihlanfeldt. “An Empir-

ical Analysis of the Property Tax Appeals Process”

Journal of Property Tax Assessment and Admin-

istation, v.10, n. 4, 2012.

[8] Ely, Richard T. Taxation in the American States

and Cities. New York: T. Y. Crowell and Co, 1888.

[9] Fisher, G. The Worst Tax: A History of the Prop-

erty Tax in America. Lawrence, KA: University

Press of Kansas, 1996.

[10] Fisher, Ronald. State & Local Public Finance. 3rd

Ed. Thomson South-Western, 2007.

[11] Gallup, 2005. “Which is the Unfairest Tax of them

all?”

[12] Hodge, Timothy, McMillen, Daniel, Sands, Gary,

and Mark Skidmore. “Assessment Inequity in a De-

clining Housing Market: The Case of Detroit.” Real

Estate Economics, 2016.

[13] International Association of Assessing Officers stan-

dard on ratio studies. Kansas City, MO: IAAO.

2013.

[14] Krupa, Olha. “An Analysis of Indiana Property Tax

Reform.” State Tax Notes, V. 65 N. 10, 2012.

7

[15] McMillen, Daniel. “Assessment of Regressivity: A

Tale of Two Illinois Counties.” Land Lines, Lincoln

Institute of Land Policy, January, 2011.

[16] McMillen, Daniel.“The effect of appeals on assess-

ment ratio distributions: Some nonparametric ap-

proaches.” Real Estate Economics, n.1, 2013.

[17] McMillen, Daniel P. and Rachel N. Weber.“Thin

Markets and Property Tax Inequities: A Multino-

mial Logit Approach.” National Tax Journal, n. 4,

2008.

[18] Metcalf, Gilbert. “The Lifetime Incidence of State

and Local Taxes: measuring Chnes During the

1980s.” In Tax Progressivity and Income Inequality,

edited by Joel Slemrod. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

UP, 1994.

[19] Musgrave, Richard A. “Commentary on Local

Property Taxation in Theory and Practice.” In

Property Taxation and Local Government Finance,

edited by Wallace E. Oates, 339. Cambridge, MA:

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2001.

[20] Phares, Donald. Who Pays State and Local Taxes.

Cambridge: Oelgeschlager, Gunn and Hain, 1980.

[21] Plummer, Elizabeth. “Evidence on the Incidence

of Residential Property Taxes Across Households.”

National Tax Journal, no. 1, 2003.

[22] Rosen, Harvey. Public Finance. 6th Ed. McGraw-

Hill Irwin, 2002.

[23] Ross, Myron H. “The Property Tax Assessment Re-

view Process: A Cause for Regressive Property Tax-

ation?” National Tax Journal, no. 1, 1971.

[24] Sands, Gary and Skidmore, Mark. “Detroit and the

Property Tax: Strategies to Improve Equity and

Enhance Revenue.” Lincoln Institute of Land Pol-

icy, 2015.

[25] Suits, Daniel B. “Measurement of Tax Progressiv-

ity.” American Economic Review, n. 4, 1977.

[26] Stanahan, Harriet A., Coorhees, William, and

Borg, Mary. “The Incidence fo the Property Tax

and Property Tax Preferences.” Researgate, 2014.

[27] Stocker, Frederick C. Proposition 13: A Ten Year

Retrospective. Cambridge, MA: The Lincoln Insti-

tute of Land Policy. 1991.

[28] Wassmer, Robert W. “Property Taxation, Property

Base, and Property Value: An Empirical Test of the

‘New View’.” National Tax Journal, No. 2, 1993.

[29] Youngman, Joan. A Good Tax: Legal and Policy

Issues for the Property Tax in the United States.

Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy,

2016.

[30] Appendix G of Marshalls Principles of Economics

(1948), Tiebout (1956), Oats (1969), Epple, Fil-

imon, and Romer (1984), Hoxby (1999), Gal-

lagherm Kurban, and Persky (2013).

8

Appendix A: Graphical results and tables

9

Figure 3: Trends in property tax appeals

10% 30% 50%

Percent of all

properties appealing

2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Year

Probability of appealing

40% 60% 80%

Percent of all properties

winning an appeal

2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Year

Probability of winning an appeal

10% 30%

Percent reduction in

taxable value

0 .5 1 1.5 2

First−pass assessment ratio

2009−2015

85% 95%100%

Percent of properties

winning an appeal

0 .5 1 1.5 2

First−pass assessment ratio

2009−2015

Cook County 2003−2015

Single Family Condominiums

Cook County is divided into three assessment areas, each of which is reassessed every three years. The cyclical pattern in the rate of

appeal observed in the first graph of this panel reflects the fact that there are many more properties in the City of Chicago, the first

assessment traid, than there are in the other two triads.

10

Figure 4: Impact of the Housing Bubble on volume and prices in Cook County’s housing market.

$150k $200k $250k $300k $350k

Sale value of homes

(net personal property)

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Tax year

by triennial reassessment area

Median sale value of homes

0 10000 20000 30000 40000

Residential sales

(thousands of sales)

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Tax year

by triennial reassessment area

Volume of residential sales

Chicago NW Suburbs SW Suburbs

11

Figure 5: Price-Related Differential

1 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

year

Single−Family Condominiums

Price−related differential

12

Figure 6: Correlation between condominium building size and probabilty of appeal

0% 20% 40%

Probability of appealing

0 200 400 600 800

Number of units in

condominium building

By size of building

Probability of appealing

13

Figure 7: Regressivness in property taxes and assessments

.005 .01 .015 .02 .025

Effective tax rate on housing wealth

$500k $1mln $1.5mln $2mln

Sale value of property

For 113750 properties sold in Chicago 2009−2015.

Chicago 2009−2015

Effective tax rates

.5 1 1.5

Assessment ratios

$500k $1mln $1.5mln $2mln

Sale value of property

For 230177 properties sold in Cook County 2009−2015.

Cook County 2009−2015

Assessment Ratios

Single−Family Condominiums

14

Figure 8: Demographic correlates with effective tax rates

.012 .013 .014 .015 .016

Effective Tax Rate

on housing wealth

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

% African American

.01 .012 .014 .016 .018

Effective Tax Rate

on housing wealth

0% 20% 40% 60% 80%

% Hispanic

1.3% 1.5% 1.7%

Effective Tax Rate

on housing wealth

$31K $5K $100K $120K

Household income

.01 .012 .014 .016 .018

Effective Tax Rate

on housing wealth

20% 40% 60% 80%

% College Educated

For 97918 properties sold between 2009−2015

Chicago 2009−2015

15

Figure 9: Map of probability of filing a tax appeal by 2010 Cenusus tract

Quintiles of probability

of appealing

5th quintile

4th quintile

3rd quintile

2nd quintile

1st quintile

Cook County 2010 Census Tracts 2009−2015

Appeal rates

16

Figure 10: Map of post-appeal assessment ratios

Quintiles of post−appeal

assessment ratio

5th quintile

4th quintile

3rd quintile

2nd quintile

1st quintile

Cook County 2010 Census Tracts 2009−2015

Final Assessment Ratios

17

Figure 11: Map of mean effective tax rate by 2010 Cenusus tract

Quintiles of effective

tax rates

5th quintile

4th quintile

3rd quintile

2nd quintile

1st quintile

2010 Chicago Census Tracts 2009−2015

Effective tax rates

18

Figure 12: Map of mean residential sale value by 2010 Cenusus tract

Quintiles of mean

property value

5th quintile

4th quintile

3rd quintile

2nd quintile

1st quintile

2010 Cook County Census Tracts 2009−2015

Mean home value

19

Figure 13: Effect of applying a uniform tax rate to properties sold in 2011

−2 0 2 4 6 8

Avg. difference in uniform rate and

actual tax bills

(Thousands of $)

30 130 210 360 2940

Sale price of property

(Thousands of $)

1%

Uniform rate

2%

3%

Effective tax rate

on housing wealth

30 130 210 360 2940

Sale price of property

(Thousands of $)

For 13539 properties sold in Chicago in 2011

2011

20

Table 1: Effect of appeals on PRD by year

Year Number of

sales

First-pass

assessments

Margin of

error for

first-pass PRD

Final

assessments

Effect of

appeals on

PRD

Condominiums

2003 23647 .9804941 .0009667 .9864979 .0060037

2004 24687 .9992108 .0010699 1.0029 .0036888

2005 26361 1.003314 .001001 1.005927 .0026129

2006 22623 .9929795 .00108 .9989655 .005986

2007 20373 1.020422 .0013968 1.020143 -.0002795

2008 12757 1.079148 .002971 1.086757 .0076089

2009 13497 1.111139 .0048721 1.126737 .0155981

2010 12155 1.214219 .0089586 1.216193 .0019739

2011 10932 1.453566 .0112359 1.487601 .0340348

2012 11989 1.140018 .0063924 1.161866 .0218487

2013 15701 1.099589 .002935 1.09847 -.001119

2014 15059 1.063391 .0022468 1.069806 .0064142

2015 15057 1.002597 .0017878 1.015389 .0127921

Single-family homes

2003 47848 1.033248 .001004 1.034837 .0015888

2004 51599 1.016408 .0010209 1.018406 .0019974

2005 52785 1.035401 .0011508 1.037576 .0021751

2006 40962 1.025603 .001064 1.028046 .0024426

2007 28624 1.025314 .0015414 1.03179 .0064753

2008 17352 1.082953 .0034686 1.091926 .0089734

2009 16782 1.098144 .0034911 1.112224 .0140803

2010 17776 1.136879 .0037595 1.152979 .0161002

2011 16221 1.208911 .0052592 1.218689 .0097774

2012 18426 1.125253 .0034523 1.135212 .0099592

2013 24365 1.105195 .0024773 1.109264 .0040691

2014 21290 1.0922 .0021832 1.094257 .0020574

2015 20927 1.056025 .0019525 1.063649 .0076243

21

Table 2: Correlates with appealing, winning appeal

First-pass Probability of Probability of % reduction in Effective tax

assessments appealing winning an appeal taxable value rate

Property Characteristics

Sale price 4.87e-13 3.57e-13

∗∗∗

8.69e-13

∗∗∗

4.69e-13

∗∗∗

-1.34e-13

∗

($100,000) (1.89) (3.66) (4.35) (3.64) (-2.39)

Ratio of first-pass estimated 0.0315

∗∗∗

0.236

∗∗∗

0.174

∗∗∗

1.099

∗∗∗

market value to realized market value (6.61) (14.67) (5.45) (33.68)

Condominium 0.00631 0.0842

∗∗∗

0.139

∗∗∗

0.0201 -0.00741

(0.37) (13.51) (9.34) (1.18) (-1.01)

Number of units in -0.00442

∗∗

0.00620

∗∗∗

0.000148 0.00225 -0.00457

∗∗∗

a building (-3.18) (10.53) (0.16) (1.48) (-8.70)

Squared number of units 0.0000174 -0.0000246

∗∗∗

-0.000000105 -0.00000381 0.0000239

∗∗∗

in a building (1.49) (-4.01) (-0.01) (-0.46) (3.31)

Property Characteristics

% non-white 0.0100

∗∗∗

-0.000267

∗∗∗

0.00343

∗∗∗

-0.000769 0.00279

∗∗∗

and/or hispanic (50.22) (-4.15) (12.38) (-0.76) (8.69)

% Holding a BA or higher 1.452

∗∗∗

0.183

∗∗∗

0.458

∗∗∗

-0.231

∗∗∗

0.471

∗∗∗

(29.32) (9.53) (10.90) (-4.65) (10.22)

N 589259 589259 90016 90016 279428

r2 0.782 0.267 0.661 0.00196 0.913

t statistics in parentheses

Errors clustered on 2010 Census Tracts

∗

p < 0.05,

∗∗

p < 0.01,

∗∗∗

p < 0.001

22

Appendix B: Alternate measures of vertical equity

In addition to PRD, I also calculate Price Related

Bias (PRB), and a version of the Suites Index. Price

Related Bias is calculated by regressing the adjusted as-

sessment ratio against the adjusted mean sales price for

a given period, and capturing the resulting coefficient β

1

.

I trim the first and last percentile of assessment ratios

from my annual regression samples, which is consistent

with standard assessment practices. My regression is:

Y

i

= β

0

+ β

1

X

i

+

i

(2)

where

Y

i

=

V

i

− Median(E

CCAO

[V ])

Median(E

CCAO

[V ])

(3)

and

X

i

=

ln(

E

CC AO

[V

i

]

(Median(E

CC AO

[V ])

+ V

i

)

2ln(2)

(4)

Where Med(E

CCAO

[V ]) is the median CCAO estimated

market value.

PRD is positively correlated with regressiveness,

while PRB is negatively correlated with regressiveness.

The standard “acceptable” bounds for PRB are 0 ± .03.

The PRB may be interpreted as the effect of doubling

a property’s value on that property’s assessment ratio.

In 2015, the post-appeal PRB figure for the County was

-.042. The interpretation of this coefficient is that dou-

bling a property’s value would be associated with an

decrease in its assessment ratio by 4.2%. As with PRD,

I calculate PRB from both first and final assessment ra-

tios to measure the impact of appeals on progressiveness,

and find qualitatively identical results to PRD.

The Suites Index is given:

S = 1 − (1/5000)

Z

100

0

T (Y )dy (5)

S ≈

N

X

i=0

[T (Y

i

) + T (Y

i−1

)][Y

i

− Y

i−1

] (6)

where Y and T (Y ) are the cumulative percentage of the

total income and the corresponding cumulative percent-

age of tax burden, respectively. I use property value in

lieu of income, since I cannot directly observe individual

taxpayers’ incomes. I therefore calculate this Suites in-

dex using the subsample of properties which sold in each

year.

Figure 14 shows the “Suites Curve” plotted with a

45 degree line, representing a proportional distribution

of taxes across property values. In the figure, the Suites

Curve lies above the proportional line, indicating that

lower value properties bear a disproportional larger por-

tion of the property tax burden.

Since the Suites Index can only be calculated using

actual taxes paid, I cannot calculate a pre- and post-

appeals Index. In order to recalculate taxes for individ-

ual taxpayers supposing they had not appealed, I would

have to make an assumption about the effect if a larger

tax base on the statutory tax rate. Tax levies are set

ex ante the determination of the tax base, and tax rates

are determined simply by the ratio of the tax levy to

the base. Changing the base by excluding appeals will

increase the statutory rate in a somewhat unpredictable

way. Thus, I present indices only for post-appeal taxes.

23

Figure 14: Price-Related Differential

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1

Cumulative proportion of total tax

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1

Cumulative proportion of total property values

Suites Curve Proportional Distribution

Cook County, 2003−2015

Suites Curve

24

Table 3: Price-related Bias and Suites Indices

Year Number of

sales

First-pass

assessments

Final

assessments

Margin of

error for

first-pass

PRB

Effect of

appeals on

PRB

Suites Index Margin of

errror

2003 71495 -.0252729 -.02802 .0008249 -.0027471 .0037802 .0015675

2004 76286 -.0169512 -.0185279 .0008047 -.0015767 -.0048736 .0014858

2005 79146 -.037817 -.0383912 .0008311 -.0005742 -.003165 .0015807

2006 63585 -.0164822 -.0196375 .0008008 -.0031553 .0060896 .001734

2007 48997 -.0205835 -.0219423 .0010023 -.0013588 -.0183435 .0019752

2008 30109 -.0720933 -.0780768 .0014491 -.0059834 -.0779939 .00343

2009 30279 -.118095 -.1312703 .0021423 -.0131753 -.1106438 .0044872

2010 29931 -.146046 -.1514736 .0020353 -.0054276 -.1760897 .0064089

2011 27153 -.1864577 -.1939308 .0020569 -.0074731 -.3616682 .0078987

2012 30415 -.1304321 -.1353229 .0014716 -.0048909 -.1064669 .0042314

2013 40066 -.1122607 -.1064409 .0011106 .0058197 -.0896962 .0029003

2014 36349 -.0866059 -.0853196 .0010966 .0012862 -.079108 .003676

2015 35984 -.0353427 -.0426762 .001061 -.0073335 -.0325671 .0022702

25