Media and Communication

2024 • Volume 12 • Arcle 7482

https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.7482

ARTICLE

Open Access Journal

Unraveling US Newspapers’ Digital and Print Subscripons in the

Context of Price, 2016–2022

Hsiang Iris Chyi

1

and Sun Ho Jeong

2

1

School of Journalism and Media, The University of Texas at Austin, USA

2

Department of Mass Communication, Konkuk University, South Korea

Correspondence: Hsiang Iris Chyi ([email protected]xas.edu)

Submitted: 31 July 2023 Accepted: 10 October 2023 Published: 6 February 2024

Issue: This article is part of the issue “Examining New Models in Journalism Funding” edited by Merja

Myllylahti (Auckland University of Technology) and James Meese (RMIT University), fully open access at

https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.i398

Abstract

Despite industry‐wide efforts in digitally transforming news organizations, research showed that most

newspapers’ legacy products still outperformed the same newspaper’s digital offerings in terms of

engagement, circulation, readership, pricing, advertising, and subscription revenue—all by a wide margin. But

Covid‐19 created an unprecedented scenario where the need for instant, local news updates, the fear of

contacting anything tangible, and financial stress may have changed consumer behavior. To assess the state

of the newspaper industry, this study analyzes short‐term and long‐term trends in US newspapers’ digital

and print circulation before and during the pandemic. The analysis considered price, an important factor

often neglected in discussions about newspaper demand. Utilizing rich industry data, this study analyzed

18 US metro daily newspapers’ circulation trends during 2016–2022. The results revealed that digital

circulation increased rapidly after the onset of Covid‐19 but subsequently decreased after reaching the peak

in Q3 2021. Print circulation continued its rapid decline since 2016, accompanied by continuous, substantial

price hikes for print subscriptions—a typical print subscription now costs over $1,000 a year. Despite

circulation declines, the print edition remains the core product, with more subscribers paying far more than

digital subscribers. Because of the immense price gap (6 to 1), the seemingly promising increase in digital

subscriptions during Covid‐19 could not generate nearly as much revenue to cover the loss on the print side,

resulting in a substantial loss in total subscription revenue. The state of the US newspaper industry needs

immediate attention.

Keywords

Covid‐19; digital subscription; digital transformation; newspaper circulation; newspapers; subscription

revenue

© 2024 by the author(s), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY).

1

1. Introduction

Since the onset of digital journalism, dating back to the mid‐1990s, the economic sustainability of online

journalism has been a subject of scrutiny, which at its core revolves around the viability of digital

subscriptions as a source of funding for journalism. Despite longstanding, industry‐wide efforts in digitally

transforming newspaper firms and a large number of users accessing news online (Newman et al., 2023),

digital subscriptions have not turned into a reliable stream of revenue (Chyi & Ng, 2020; Edmonds, 2022).

Research on consumer behavior pointed to users’ lukewarm responses to newspapers’ digital offerings—in

terms of use (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2017; Thurman, 2014, 2017) and subscription (Chyi, 2012; Chyi & Ng,

2020)—as a significant reason underlying news organizations’ challenges in monetizing digital content. This

also explains why the vast majority of US newspapers continue to heavily rely on their legacy product, as it

remains the primary source of both advertising and subscription revenue (Chyi & Ng, 2020; Pew Research

Center, 2023). To compensate for the substantial loss in advertising revenue since the 2008 recession, the

industry sought short‐term profits by sharply raising the price of the print product (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2019).

The print edition, once considered the “cash cow” product (Picard, 2003), has also experienced substantial

declines in circulation in recent years (Pew Research Center, 2023).

While newspaper firms found themselves caught between an unsuccessful digital experiment and a rapidly

weakening print product, Covid‐19 created a scenario that may have resulted in a shift in newspapers’

financial landscape. First, during the pandemic, the demand for instant, local news updates skyrocketed (Kim

et al., 2022). Second, the reluctance to interact with tangible objects at the onset of the pandemic might

have weakened the existing demand for the printed product. The financial stress induced by the pandemic

also might have driven print subscribers to seek cheaper alternatives, such as the same newspaper’s digital

offerings. All these factors could have provided new momentum for newspaper firms, which have been

grappling with digital transformation for more than two decades. This scenario presents a great opportunity

to re‐assess news consumers’ willingness to pay for newspapers’ print and digital offerings.

Given circulation is the most important indicator of newspaper demand, this study seeks to unravel the

print‐digital gap by identifying both short‐term and long‐term trends in 18 US newspapers’ digital and print

circulation from 2016 to 2022—before and during the pandemic. Additionally, as previous research has

highlighted, price, the determinant of quantity demanded (Hoskins et al., 2004), is often neglected in

industry discussion and media coverage on newspaper demand (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2019). Consequently,

this study tracks the price of digital/print subscriptions over time and examines digital/print circulation in

this context. By analyzing both circulation and pricing data, this study also presents an evaluation of

subscription revenue trends.

While newspapers are confronting existential challenges, this study serves three primary goals: (a) to provide

a systematic, up‐to‐date examination of the state of newspapers through identifying long‐term and

short‐term industry trends in the appropriate economic context; (b) to contribute to media economics

research by examining digital news consumption in depth; and (c) to offer a critical review on US newspaper

firms’ technology‐centric product strategy.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

2

2. Digital Subscriptions: Research Inquiries

2.1. History of Industry Attempts

In the 1990s, some US newspapers worried about the “cannibalization effect,” fearing that a free web edition

might erode their print subscriber base, but the vast majority opted for the advertising model, giving content

away for free for well over a decade. The Wall Street Journal was a prominent outlier, charging 150,000 online

readers a $49 annual subscription fee back in 1998 (Steinbock, 2000).

After the internet bubble burst in 2000, while some publishers proposed to charge for the content they offered

online (Outing, 2002, as cited in Chyi, 2012) because “there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch,” users were

not ready to pay for online news. The sign‐up rate for paid‐for newspaper sites was as low as 0.2% to 2.6%

of the print circulation, and 71% of online news users said they would go somewhere else because free sites

were readily available (Borrell & Associates, 2001, as cited in Chyi, 2012). The notion that content must be

free unless it is highly specialized (Carlson, 2003) and “it is impossible to charge for general news content”

(Herbert & Thurman, 2007, p. 215) gained widespread acceptance in the industry.

The New York Times dropped its first fee‐based experiment (TimesSelect) in 2007, on which Jeff Jarvis (2007)

commented, “With it goes any hope of charging for content online. Content is now and forever free” (para. 1).

The vast majority of US newspaper sites continued giving content away for free (American Press Institute &

ITZBelden, 2009), with notable exceptions of The Wall Street Journal, The Arkansas Democrat‐Gazette (Hussman,

2007), and The Albuquerque Journal (Windsor, 2009).

After the 2008 recession, “the [industry’s] dream of getting people to pay” recurred (Kinsley, 2009, para. 2),

and the idea was put into practice in 2011. The Dallas Morning News started a “hard paywall,” charging $16.95

a month for a digital package that included web and apps (Doctor, 2011). Weeks later, The New York Times

implemented a metered model, or a “soft paywall,” requiring online users who view more than 20 articles

(reduced to 10 in April 2012) per month to pay a subscription fee (Peters, 2011).

While some newspapers dropped their paywalls (Ananny & Bighash, 2016), most major US newspapers have

adopted the digital subscription model, charging for online news access. By 2015, among the 98 US

newspapers with a total circulation of 50,000 or more, 77 implemented some kind of paywalls around their

digital products (Williams, 2016). In 2016, the result of the US election triggered a “subscription surge” (aka

the “Trump bump”). The growing number of digital subscribers among national newspapers (Benton, 2018;

Stelter, 2017), especially The New York Times, received substantial media attention.

However, most US newspapers’ paywall experiments were not nearly as successful. Drawing on data from

2017 released by the Alliance for Audited Media ([AAM] formerly ABC, the Audit Bureau of Circulations),

Chyi and Ng (2020) empirically examined 50 major US newspapers’ digital and print subscriptions. They

revealed that most newspapers charged digital subscribers a fraction of the print subscription price, but

digital subscribership remained trivial, contributing only 3% of total reader revenue. This study triggered

questions about the disparities between some newspapers’ self‐claimed digital subscription figures and the

audited data. When media business reporter Rick Edmonds investigated the issue, he found “extreme

reluctance” among news executives to discuss these discrepancies (Edmonds, 2021).

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

3

2.2. Subscription Surge During the Pandemic?

While the industry was experimenting with the subscription model, media scholars examined its viability from

the demand side (for a detailed review, see O’Brien et al., 2020). Yet, the pandemic has created an

unprecedented scenario where multiple factors, especially the skyrocketing demand for immediate updates on

Covid‐19 developments, may have boosted digital subscriptions, triggering another “subscription surge.’’ This

study takes this opportunity to measure news consumers’ demand for newspapers’ digital subscriptions by

empirically examining short‐term and long‐term digital circulation trends, addressing this research question:

RQ1: To what extent has digital circulation increased during Covid‐19?

2.3. Print Circulation: Long‐Term and Short‐Term Trends

The decline in print circulation is a well‐established trend that has persisted for decades. Industry data (Pew

Research Center, 2023) indicated that weekday newspaper circulation has been decreasing since 1987, while

Sunday circulation has seen a decline since 1993, even with the continuous growth of the US population.

Taking a broader perspective, newspaper penetration has exhibited a steady decline of 1–2% each year since

1950 (Picard, 2008; Picard & Brody, 1997).

Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist, also shed light on the matter, noting that newspaper circulation reached

its peak in 1972, suggesting that the decline in circulation can be attributed to competition from other media

outlets such as broadcast TV news, cable news, and the internet (Varian, 2013).

During the 2008 recession, most US newspapers experienced substantial print circulation declines (Chyi

et al., 2012; Pew Research Center, 2023). During the pandemic, the financial stress induced by Covid‐19 and

the apprehension of contacting tangible things during Covid‐19 may have quickened the decline in print

circulation. To examine the state of print newspapers, this study seeks to identify short‐ and long‐term print

circulation trends, addressing the following research question:

RQ2: To what extent has print circulation declined before and during Covid‐19?

2.4. The Print‐Digital Gap in Circulation

Despite the long‐term declines in print circulation and the industry’s efforts in digitally transforming their

newspaper, the print edition remained the core product, generating the majority of subscription and

advertising revenue (Benton, 2018; Pew Research Center, 2023; Picard, 2014; Thurman, 2014, 2017).

Empirical research showed that readers responded more favorably to the same newspaper’s print product

(Chyi, 2012; Herbert & Thurman, 2007; Myllylahti, 2014; Thurman, 2014, 2017). The gap between the

“supposedly promising” digital edition and the “supposedly dying” print product was also prominent in terms

of subscribership. A pre‐Covid‐19 study compared print and digital circulation among 39 US newspapers,

revealing that print circulation exceeded digital circulation in all cases, and digital subscribers often

constituted a small, almost negligible fraction of overall circulation (Chyi & Ng, 2020). Such findings

suggested that, more than 20 years into US newspapers’ digital experiment, news consumers’ willingness to

pay for online news was still non‐existent. But the scenario triggered by Covid‐19 might have significantly

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

4

changed user behavior and narrowed or even closed the enormous print‐digital gap for the very first time.

To assess the current state of the circulation gap between print and digital, this study proposes the following

research question:

RQ3: How does print circulation compare with the same newspaper’s digital circulation before and

during Covid‐19?

2.5. Price: The Determinant of Quantity

Price is the determinant of quantity demanded (Hoskins et al., 2004). It is however often ignored in

discussions and media coverage about newspaper demand (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2019). Since the 2008

recession, in hopes of reducing reliance on rapidly diminishing advertising revenue, most daily newspapers

implemented continuous price hikes on their print subscribers. A longitudinal study tracking 25 major US

newspapers’ print subscription rates in 2008, 2012, and 2016 revealed that these newspapers’ seven‐day

home delivery prices more than doubled since the recession (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2019). The increase in

prices naturally resulted in declines in circulation, which made news headlines and fueled the perception that

“print is dying.” However, industry reports and media coverage seldom consider price as a primary driver of

circulation declines. Since price directly affects quantity demanded (and revenue), it is essential to consider

changes in price when interpreting demand for multiplatform newspaper products. To contextualize changes

in print circulation, this study tracks changes in print subscription prices, addressing this research question:

RQ4: Have print subscription prices continued to rise over time?

Economic theory suggests that the price of a related good affects demand for a product (Hoskins et al.,

2004). It is therefore essential to consider how newspaper firms price their print and digital products

simultaneously. It is no secret that newspaper firms have had difficulties charging digital subscribers a

premium price. In a study empirically examining the pricing schemes of 50 US newspapers, it was found that

a digital subscription was priced at 23% of the cost of the corresponding print edition (Chyi & Ng, 2020).

This price gap suggested that it required over four digital subscribers to generate the same amount of

revenue as a single print subscription. To re‐examine whether the existing price gap changed during

Covid‐19, this study addresses this research question:

RQ5: How does the print subscription price compare with the same newspaper’s digital subscription

price?

2.6. Impact on Subscription Revenue

Newspapers generate revenue from two major sources: advertising and circulation. According to the latest

Pew report, industry‐side advertising revenue has been declining, and in 2020, circulation revenue surpassed

advertising revenue for the first time (Pew Research Center, 2023). As a result, circulation now stands as the

primary revenue source for newspapers.

Chyi and Ng (2020) estimated that in 2017, print subscriptions contributed 97% of total subscription

revenue, while digital accounted for only 3% of such revenue. That finding resembled a final verdict

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

5

suggesting US newspapers’ industry‐wide efforts in digital transformation did not make monetary sense.

However, the digital surge during Covid‐19 might have led to a shift in newspapers’ financial landscape.

To re‐assess the share of digital subscription revenue among total subscription revenue, this study addresses

the following research question:

RQ6: To what extent do digital subscriptions contribute to overall subscription revenue?

3. Method

To identify short‐term and long‐term circulation trends and to assess the impact of Covid‐19, this study

analyzes 18 US newspapers’ digital/print circulation and pricing data during 2016–2022. Since the pandemic

triggered extensive lockdowns and restrictions in the US starting in March 2020, the analysis comprised nine

time points—four before and four after Q1 2020.

3.1. Sample

Sampling started from a list of 50 news publications featured in Pew Research Center’s 2016 State of the

News Media Report (Pew Research Center, 2017), which includes four national newspapers and 46 metro

newspapers operating in 28 states. The researchers closely examined the data source and excluded

newspapers that did not file detailed digital circulation data during 2016–2022 and those with missing data

at more than two time points. The final sample includes 18 local dailies operating in 16 states—all are leading

newspapers in their respective markets. With 18 cases, we could reasonably generalize and at the same time

examine each individual case.

3.2. Data Collection

Each newspaper’s digital/print circulation and pricing data were manually retrieved from the audit reports and

the news media statements filed for the AAM in 2016–2019, Q1 2020, Q3 2020, Q1 2021, Q3 2021, and

Q1 2022.

Since the AAM reports after 2020 no longer include pricing data, current digital subscription prices and

promotion offers were collected from each newspaper’s website from June 2020 to February 2021.

3.3. Measures and Definitions

3.3.1. Print and Digital Circulaon

The print product refers to what AAM defined as a “traditional hard copy of the newspaper,” and the digital

product refers to what AAM defined as Digital Nonreplica, which is “a digital edition that is consistent in

character and editorial content with the print edition….Advertising may differ” (AAM, 2022b). Examples of

the latter include mobile apps and restricted websites with paywalls (AAM, 2022a).

The AAM reports provide both paid and non‐paid circulation data. Since this study focuses on paying

subscribership, the analysis is centered on paid circulation, which is the number of subscribers. Total

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

6

Average Paid Circulation data (including individually paid circulation and business/traveler paid circulation)

for weekdays (i.e., average Monday–Friday or Monday only) for digital nonreplica and print products

were retrieved.

3.3.2. Print and Digital Price

The print subscription price (2016–2019) refers to the yearly price, based on 52 weeks, for the home delivery

of the print edition as listed in the AAM audit reports. After 2020 the AAM no longer provides such data.

Regarding digital subscriptions, since the AAM no longer provides pricing data after 2020, the researchers

turned to each newspaper’s website and collected the digital price of the “unlimited digital access” package,

which typically encompasses access to the website, mobile app, digital‐edition replica, and in certain cases

the e‐reader edition for the Kindle. Also retrieved from each newspaper’s website was the promotional price,

which refers to the discounted introductory price for the “unlimited digital access” package, offered to

potential subscribers for a certain period of time. Data were retrieved from June 2020 to February 2021.

3.3.3. Subscripon Revenue

Digital/print subscription revenue refers to the earnings derived from digital/print subscriptions. It is estimated

by multiplying the number of subscribers by the subscription price using the most recent data accessible

(specifically, digital and print circulation from Q1 2022, digital subscription prices from 2020–2021, and print

subscription prices from 2019).

4. Results

RQ1 concerns the increases in digital circulation (i.e., the number of digital subscribers) during Covid‐19.

The analysis revealed that most of the 18 newspapers under study, with the exception of five cases,

experienced growth in digital circulation during the pandemic. Table 1 presents data for each of the

18 newspapers across nine time points. Taken as a whole, digital circulation increased rapidly after the onset

of Covid‐19—the median rose from 10,810 in 2019 (pre‐Covid‐19) to 21,959 in Q3 2021 (the peak), but

subsequently decreased to 14,248 by Q1 2022.

Among the 18 newspapers, The Boston Globe stands out as the most successful case both for starting with

the largest digital subscribership (75,166 in 2017) and for continuously growing it during Covid‐19 (adding

139,175 more since 2019). Percentagewise, the most substantial growth in digital subscriptions was reported

by The Fort Worth Star‐Telegram (350%), followed by Newsday (207%), The Miami Herald (198%), The Boston

Globe (133%), and The Seattle Times (112%).

RQ2 concerns declines in print circulation (i.e., the number of print subscribers) before and during Covid‐19.

Table 2 presents the results. All the 18 newspapers under study reported substantial, rapid declines in print

circulation over time—the median circulation decreased from 101,378 in 2016 to 59,446 in 2019, and then

to 34,474 in Q1 2022 (there was one case with missing data in 2016). Some newspapers lost more print

subscribers than others. The Los Angeles Times, the largest newspaper on the list, has lost more than 80,000

print subscribers since 2019, which is 36% of its print circulation. Percentage‐wise, The Fort Worth

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

7

Table 1. Number of digital nonreplica subscribers (2016–2022).

State Newspaper 2016 2017 2018 2019 Q1 2020 Q3 2020 Q1 2021 Q3 2021 Q1 2022 Change

since

2019

Change

since

2019 in %

AZ The Arizona Republic 10,985 10,384 11,349 13,938 16,157 22,540 24,354 27,939 27,501 13,563 97%

CA Los Angeles Times 30,793 42,985 58,403 60,468 64,550 89,066 78,780 68,679 68,039 7,571 13%

CA Sacramento Bee 6,618 5,596 3,939 5,891 6,868 8,404 10,043 10,813 10,719 4,828 82%

CO Denver Post 4,746 3,171 2,557 8,967 18,606 25,761 30,030 29,556 2,515 −6,452 −72%

FL Miami Herald 8,242 6,492 5,779 10,695 19,612 23,306 27,136 30,677 31,859 21,164 198%

IA The Des Moines Register 5,423 6,983 6,558 7,104 6,100 6,068 5,952 6,095 5,714 −

1,390

−

20%

IN Indianapolis Star 8,347 10,424 10,558 10,925 10,905 10,693 11,102 12,075 11,158 233 2%

KS The Kansas City Star 3,617 1,819 6,025 11,053 17,843 19,431 22,222 23,802 18,183 7,130 65%

KY The Courier‐Journal 4,065 6,020 5,698 5,628 5,586 5,710 5,442 6,121 5,817 189 3%

MA The Boston Globe NA 75,166 94,593 105,015 166,712 229,027 235,518 234,398 244,190 139,175 133%

MN The Star Tribune 65,987 69,368 69,364 76,117 90,363 100,128 100,345 95,362 94,902 18,785 25%

NC Charlotte Observer 2,740 3,510 6,308 8,741 10,272 11,630 13,229 14,146 14,196 5,455 62%

NY Newsday 6,271 6,778 8,741 20,011 23,906 34,095 37,752 54,804 61,528 41,517 207%

OH Cincinnati Enquirer 8,557 10,307 9,834 10,110 10,392 9,819 10,138 11,115 9,082 −1,028 −10%

TX Fort Worth Star‐Telegram 1,336 1,620 908 2,280 7,785 8,857 10,045 10,844 10,253 7,973 350%

TX San Antonio Express‐News 4,515 4,660 7,007 9,280 8,995 12,336 16,554 20,116 4,967 −4,313 −46%

WA Seattle Times 13,523 19,318 27,429 36,228 46,962 61,012 70,267 71,974 76,704 40,476 112%

WI Milwaukee Journal Sentinel NA NA 9,653 18,396 17,303 15,826 16,674 16,130 14,300 −4,096 −22%

Median 6,445 6,778 7,874 10,810 16,730 17,629 19,448 21,959 14,248 6,293 44%

Mean 11,610 16,741 19,150 23,380 30,495 38,539 40,310 41,369 39,535 16,154 —

Sum 290,780 —

Count (out of 18) 16 17 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 18

Note: NA = not available. Source: AAM (2016–2022).

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

8

Table 2. Number of print subscribers (2016–2022).

State Newspaper 2016 2017 2018 2019 Q1 2020 Q3 2020 Q1 2021 Q3 2021 Q1 2022 Change

since 2019

Change

since 2019

in %

AZ The Arizona Republic 163,678 142,354 124,944 99,676 101,162 80,132 80,992 66,545 68,437 −31,239 −31%

CA Los Angeles Times 331,337 296,572 254,906 221,517 190,875 173,485 162,272 146,724 140,795 −80,722 −36%

CA Sacramento Bee 104,486 88,911 72,673 58,199 52,703 49,569 44,808 39,656 35,923 −22,276 −38%

CO Denver Post 144,782 122,709 105,553 89,530 68,463 64,153 60,878 55,916 51,622 −37,908 −42%

FL Miami Herald 68,103 57,845 44,067 33,896 33,706 28,829 24,240 21,580 21,177 −12,719 −38%

IA The Des Moines Register 66,190 60,249 51,726 42,729 33,877 32,220 30,717 28,859 26,246 −

16,483

−

39%

IN Indianapolis Star 93,399 82,125 66,374 52,202 46,291 43,741 40,869 38,475 33,024 −19,178 −37%

KS The Kansas City Star 101,378 85,996 73,769 60,693 53,589 45,762 40,841 35,736 32,820 −27,873 −46%

KY The Courier‐Journal 84,338 76,330 62,657 49,277 41,509 38,828 35,717 32,413 28,995 −20,282 −41%

MA The Boston Globe NA 128,455 116,992 104,372 82,536 78,839 76,114 71,965 67,293 −37,079 −36%

MN The Star Tribune 182,913 171,257 156,777 142,219 120,805 119,804 113,310 108,643 102,354 −39,865 −28%

NC Charlotte Observer 78,780 67,441 55,316 47,373 42,388 39,003 34,046 29,685 25,763 −21,610 −46%

NY Newsday 202,853 179,892 159,309 140,207 123,010 117,853 110,479 103,325 96,879 −43,328 −31%

OH Cincinnati Enquirer 84,512 74,609 64,373 51,550 40,937 39,183 37,421 34,420 31,179 −20,371 −40%

TX Fort Worth Star‐Telegram 82,445 72,993 61,650 50,976 39,170 34,697 29,804 25,882 23,358 −27,618 −54%

TX San Antonio Express‐News 70,467 59,098 51,904 45,586 41,590 36,170 33,037 30,522 29,106 −16,480 −36%

WA Seattle Times 154,049 142,704 129,845 119,311 103,832 99,114 94,157 88,909 84,084 −35,227 −30%

WI Milwaukee Journal Sentinel 124,137 112,580 97,909 80,145 61,816 57,782 53,495 50,214 46,106 −34,039 −42%

Median 101,378 87,454 73,221 59,446 53,146 47,666 42,839 39,066 34,474 −27,746 −38%

Mean 125,756 112,340 97,264 82,748 71,014 65,509 61,289 56,082 52,509 −30,239 —

Sum −544,297 —

Count (out of 18) 17 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 18

Note: NA = not available. Source: AAM (2016–2022).

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

9

Star‐Telegram suffered the most significant decline, losing 54% of its print circulation, while The Kansas City

Star and Charlotte Observer both experienced a 46% decrease. The Star Tribune, despite outperforming the

rest of the newspapers in retaining print circulation, also lost 28% of its print subscribers during Covid‐19.

These results seem appalling. The subsequent analysis would contextualize these declines with pricing

information.

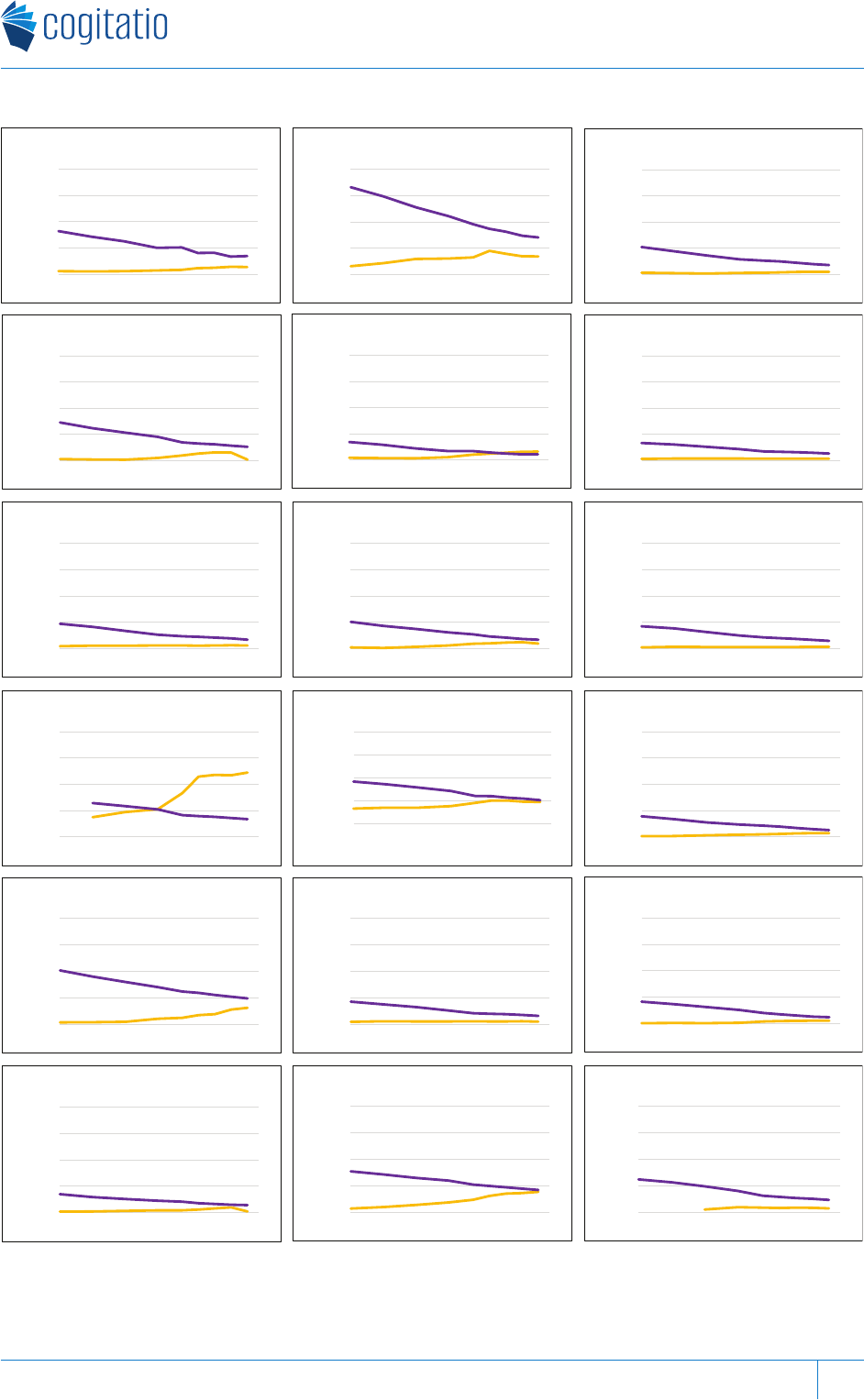

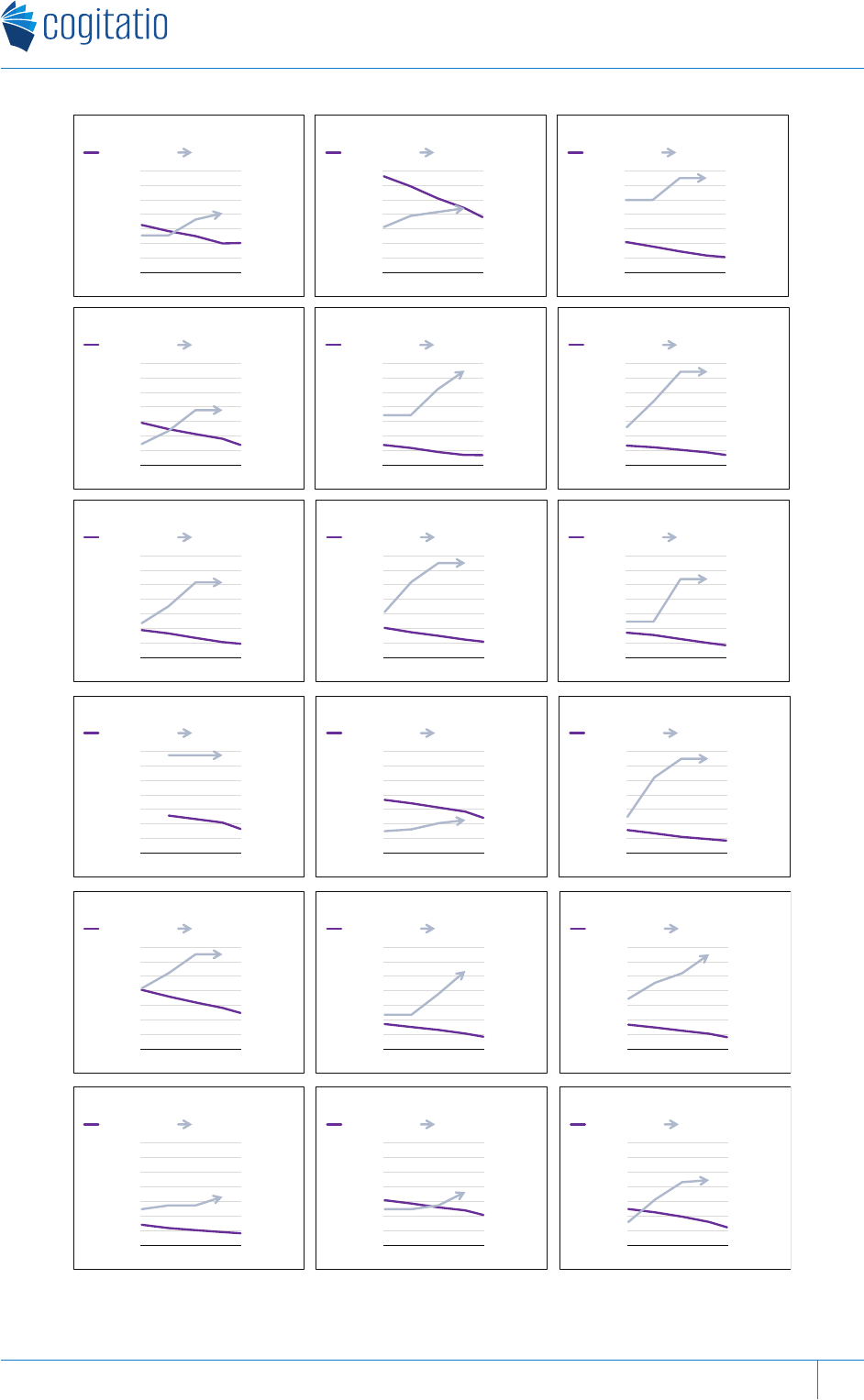

RQ3 concerns the extent to which Covid‐19 has narrowed or closed the print‐digital gap in circulation.

The analysis compared print and digital circulation before and during Covid‐19 for each of the

18 newspapers under study. Figure 1 presents the results. The enormous gap between print and digital

circulation has indeed narrowed significantly for all the 18 newspapers under study. In two cases (The Boston

Globe and The Miami Herald) the gap closed—meaning digital circulation surpassed print circulation during

Covid‐19, a pattern unseen in the pre‐Covid‐19 era. For the remaining 16 newspapers, however, the print

edition remains the primary product in terms of circulation despite the digital surge during the pandemic.

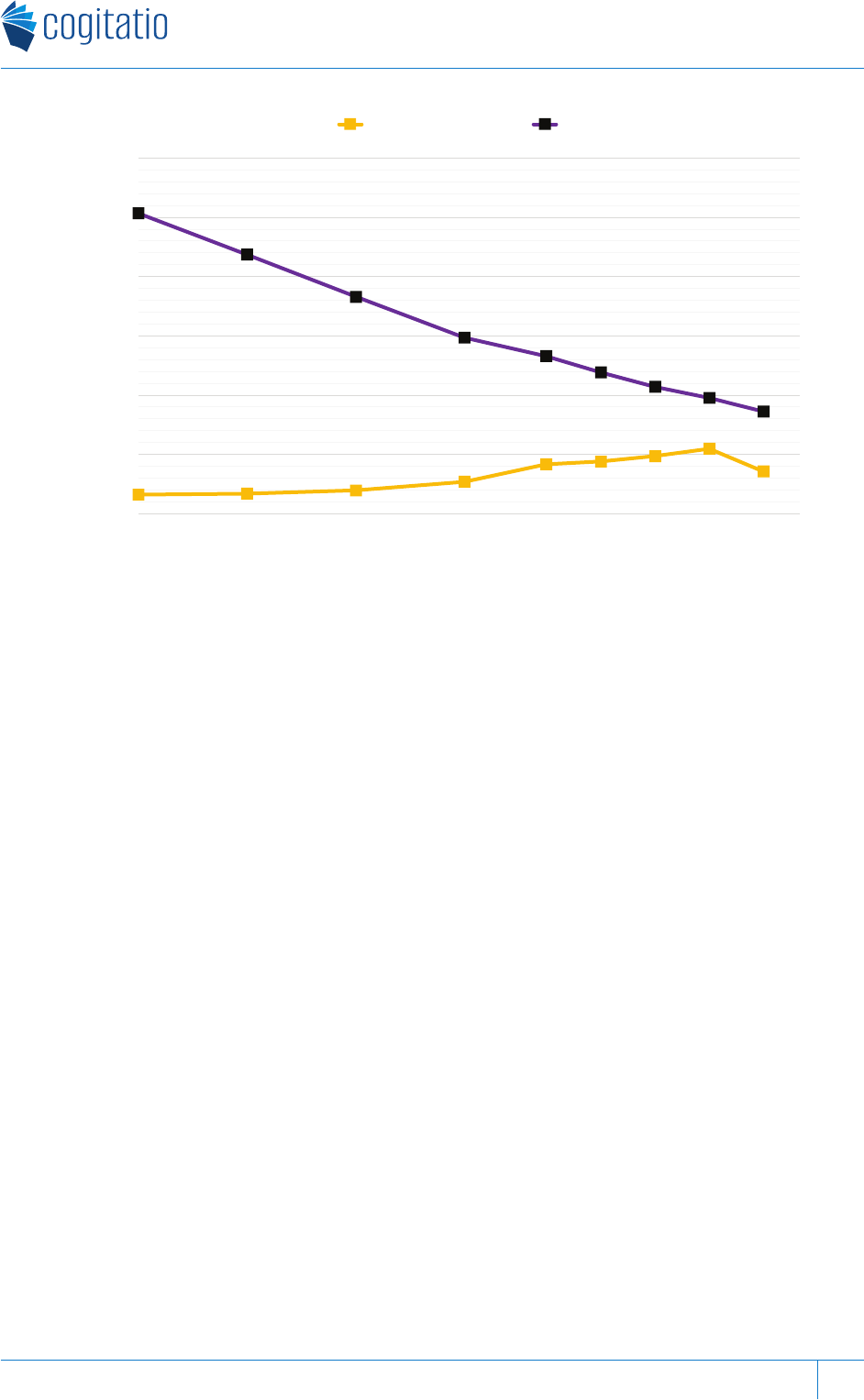

To present the overall picture, Figure 2 summarizes the aggregate digital/print circulation data (median) of

the 18 newspapers under study. Print circulation keeps declining, while digital circulation showed significant

growth during the pandemic until the peak around Q3 2021. The print‐digital gap has significantly narrowed;

however, print circulation (with a median of 34,474 across 18 newspapers) still exceeds digital circulation (with

a median of 14,248) by a considerable margin.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

10

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

The Arizona Republic

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Sacramento Bee

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Los Angeles Times

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Miami Herald

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

The Des Moines Register

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Denver Post

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Indianapolis Star

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

The Kansas City Star

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

The Courier-Journal

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

The Boston Globe

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2

0

16

2

0

17

2

0

18

2

0

19

2

02

0

2

0

21

2

0

22

The Star Tribune

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Charlo!e Observer

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Newsday

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Cincinna" Enquirer

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

San Antonio Express-News

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Sea!le Times

0

100000

200000

300000

400000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Milwaukee Journal Sen"nel

Figure 1. The print‐digital circulation gap before and during Covid‐19. Note: The purple line depicts print

circulation (source: Table 2); the yellow line depicts digital nonreplica circulation (source: Table 1).

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

11

6,445

6,778

7,874

10,810

16,730

17,629

19,448

21,959

14,248

101,378

87,454

73,221

59,446

53,146

47,666

42,839

39,066

34,474

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

digital nonreplica print

Figure 2. Digital and print circulation before and during Covid‐19 among 18 newspapers. Note: The purple line

depicts median print circulation (source: Table 2); the yellow line depicts median digital nonreplica circulation

(source: Table 1).

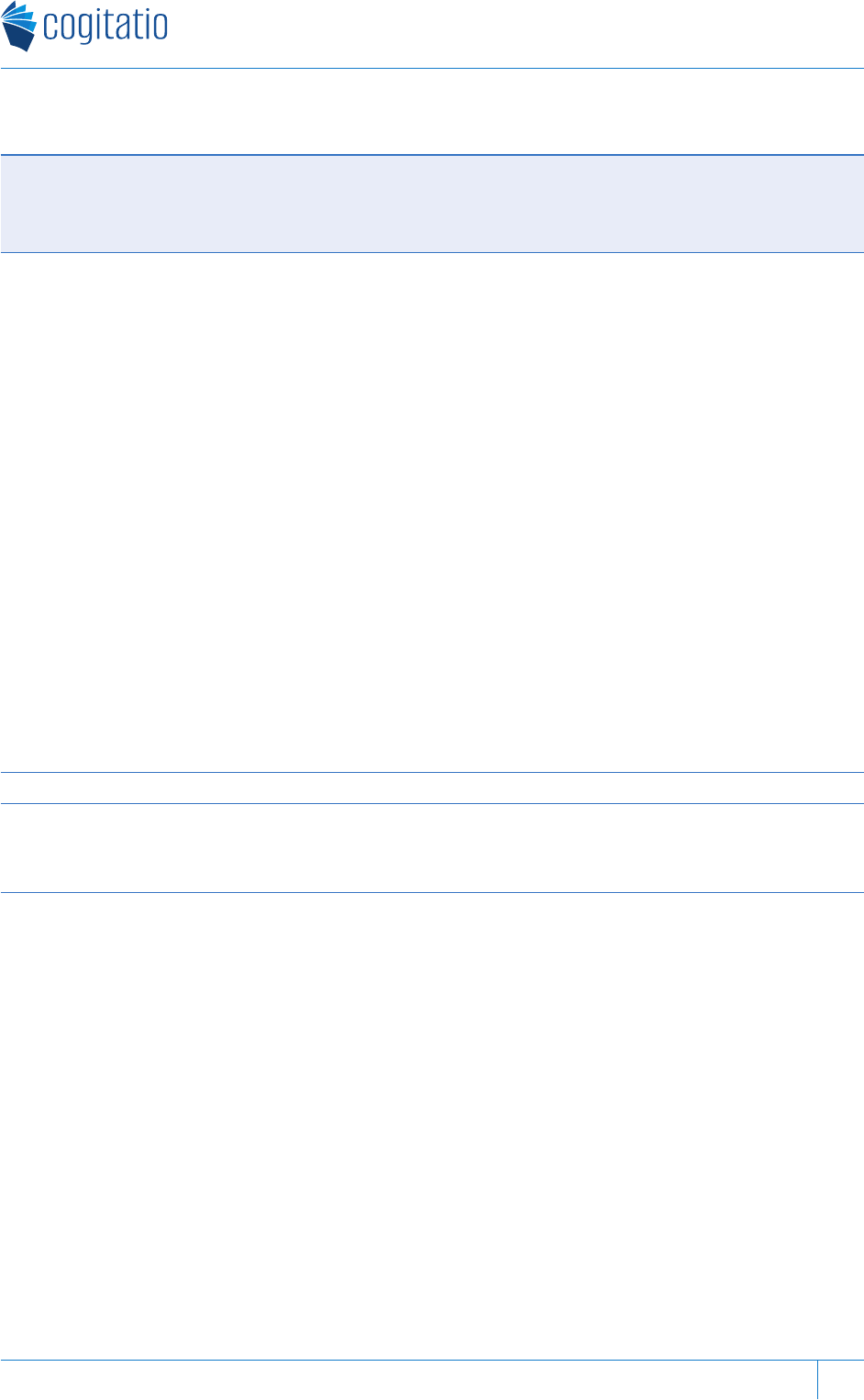

RQ4 questioned whether print subscription prices continued to rise over time. Table 3 presents changes in

home delivery prices for each of the 18 newspapers, and the answer is yes. Aggregately, the annual median

subscription price increased from $499 in 2016 (there was one case with missing data this year) to $1,075

in 2019 (data after 2020 are unavailable). In other words, these papers charged their print readers about

twice as much (or $564 more) in merely three years. All but one newspaper significantly increased the print

subscription price since 2016 (ranging from 30% to 178%), with The Boston Globe being the only exception.

This newspaper began charging its print subscribers a whopping annual rate of $1,347 as early as 2017.

A closer examination of how individual newspapers priced their legacy product revealed that some papers

were more radical than others. In addition to The Boston Globe, the most expensive print newspaper on the

list, Sacramento Bee, Miami Herald, The Kansas City Star, Charlotte Observer, and Fort Worth Star‐Telegram also

charge print subscribers $1,300 a year.

Given that price is the determinant of quantity demanded, the continuous declines in print circulation should

be understood in the context of the corresponding subscription price. Figure 3 visualizes simultaneously the

circulation and pricing data for each of the 18 newspapers from 2016 to 2019. In almost all cases, print

circulation declines were accompanied by substantial increases in price.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

12

Table 3. Continuous increases in print subscription price.

State Newspaper 2016 2017 2018 2019 Change 2016

to 2019

Rao

2019/2016

AZ The Arizona Republic $510 $510 $728 $816 $306 1.60

CA Los Angeles Times $624 $780 $832 $884 $260 1.42

CA Sacramento Bee $999 $999 $1,300 $1,300 $301 1.30

CO Denver Post $286 $468 $754 $754 $468 2.64

FL Miami Herald $684 $684 $1,040 $1,300 $616 1.90

IA The Des Moines Register $516 $876 $1,284 $1,284 $768 2.49

IN Indianapolis Star $468 $702 $1,032 $1,032 $564 2.21

KS The Kansas City Star $623 $1,040 $1,300 $1,300 $677 2.09

KY The Courier‐Journal $492 $492 $1,078 $1,078 $586 2.19

MA The Boston Globe NA $1,347 $1,347 $1,347 NA NA

MN The Star Tribune $299 $324 $410 $453 $154 1.52

NC Charlotte Observer $499 $1,040 $1,300 $1,300 $801 2.61

NY Newsday $831 $1,039 $1,299 $1,299 $468 1.56

OH Cincinnati Enquirer $468 $468 $754 $1,072 $604 2.29

TX Fort Worth Star‐Telegram $687 $910 $1,040 $1,300 $613 1.89

TX San Antonio Express‐News $494 $546 $546 $663 $169 1.34

WA Seattle Times $493 $493 $546 $728 $235 1.48

WI Milwaukee Journal Sentinel $320 $627 $864 $890 $570 2.78

median 499 693 1,036 1,075 564 1.90

mean 547 741 970 1,044 480 —

count 17 18 18 18 17 17

Note: NA = not available. Source: AAM (2016–2019).

RQ5 questioned how the print subscription price compares with the same newspaper’s digital subscription

price. Table 4 presents the latest pricing data accessible. Results indicated that the annual price for a print

subscription reached a record high by 2019 (median = $1,075). In contrast, a digital subscription was priced

at $181 during the pandemic. It takes six digital subscribers to generate the same revenue from one single

print subscription.

The price gap is most prominent for Fort Worth Star‐Telegram, The Kansas City Star, Newsday, Sacramento Bee,

Miami Herald, Charlotte Observer, The Des Moines Register, and The Boston Globe, where a print subscription

costs $1,000 more than the same newspaper’s digital edition.

Table 4 also presents each newspaper’s promotional price for new digital subscribers during Covid‐19.

The median is $0.25 a week, while The Boston Globe and The Des Moines Register offered introductory rates

as low as $0.04 a week.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

13

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

The Arizona Republic

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Los Angeles Times

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Sacramento Bee

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Denver Post

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Miami Herald

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

The Des Moines Register

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Indianapolis Star

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

The Kansas City Star

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

The Courier-Journal

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

The Boston Globe

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

The Star Tribune

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Charlo!e Observer

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Newsday

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Cincinna" Enquirer

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

San Antonio Express-News

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Sea!le Times

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

2016 2017 2018 2019

Price

Circula!on

Milwaukee Journal Sen"nel

Print circula!on Print subscrip!on price

Figure 3. Print circulation declines in the context of price. Source: Tables 2 and 3 (AAM no longer reports

pricing data after 2020).

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

14

Table 4. Comparing print and digital subscription prices.

State Newspaper Print price

a

(yearly)

Digital

price

b

(yearly)

Dierence

Print–

digital

Digital

promoonal

price

b

(weekly)

AZ The Arizona Republic $816 $120 $696 15% $0.08

CA Los Angeles Times $884 $192 $692 22% $0.25

CA Sacramento Bee $1,300 $192 $1,108 15% $0.25

CO Denver Post $754 $180 $574 24% $0.25

FL Miami Herald $1,300 $192 $1,108 15% $0.50

IA The Des Moines Register $1,284 $240 $1,044 19% $0.04

IN Indianapolis Star $1,032 $108 $924 10% $0.25

KS The Kansas City Star $1,300 $160 $1,140 12% $0.50

KY The Courier‐Journal $1,078 $108 $970 10% $0.25

MA The Boston Globe $1,347 $333 $1,014 25% $0.04

MN The Star Tribune $453 $182 $271 40% $0.25

NC Charlotte Observer $1,300 $192 $1,108 15% $0.50

NY Newsday $1,299 $181 $1,118 14% $0.25

OH Cincinnati Enquirer $1,072 $120 $952 11% $0.08

TX Fort Worth Star‐Telegram $1,300 $100 $1,200 8% $0.50

TX San Antonio Express‐News $663 $70 $593 11% $0.24

WA Seattle Times $728 $192 $536 26% $0.25

WI Milwaukee Journal Sentinel $890 $108 $782 12% $0.25

Median $1,075 $181 $961 15% $0.25

Mean $1,044 $165 $880 — $0.26

Count 18 18 18 18 18

Rao

digital /

print

Source:

a

AAM (2019),

b

18 newspapers’ websites, 2020–2021.

RQ6 concerns the share of digital subscription revenue among total subscription revenue. Table 5 presents

the estimates. While The Boston Globe stands out with the highest digital subscription revenue share (47.3%)

among the 18 newspapers, the median is 4.9%, suggesting that digital subscription revenue remains a fraction

of total subscription revenue for the vast majority of newspapers.

Overall, from 2019 to Q1 2022, the 18 newspapers as a group gained 290,780 digital subscribers while losing

544,297 print subscribers. Given the gigantic price gap (one to six), a substantial decline in total subscription

revenue is the outcome.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

15

Table 5. Estimated share of digital subscription revenue among total subscription revenue.

State Newspaper Digital subscripon revenue/total

subscripon revenue

AZ The Arizona Republic 5.6%

CA Los Angeles Times 9.5%

CA Sacramento Bee 4.2%

CO Denver Post 1.1%

FL Miami Herald 18.2%

IA The Des Moines Register 3.9%

IN Indianapolis Star 3.4%

KS The Kansas City Star 6.4%

KY The Courier‐Journal 2.0%

MA The Boston Globe 47.3%

MN The Star Tribune 27.1%

NC Charlotte Observer 7.5%

NY Newsday 8.1%

OH Cincinnati Enquirer 3.2%

TX Fort Worth Star‐Telegram 3.3%

TX San Antonio Express‐News 1.8%

WA Seattle Times 19.4%

WI Milwaukee Journal Sentinel 3.6%

Median 4.9%

Count 18

Note: These estimates were based on the most recent data accessible—digital and print circulation from Q1 2022, digital

subscription prices from 2020–2021, and print subscription prices from 2019.

5. Discussion

Utilizing rich industry data, this study presents a longitudinal analysis of circulation trends in a group of US

newspapers. It re‐assesses user demand for paid‐for newspapers in digital and print formats before and

during Covid‐19. The results revealed that, during the pandemic, print circulation continued its decline,

while digital subscriptions gained new momentum and experienced substantial growth, reaching a peak in

Q3 2021. This “Covid‐19 bump,” however, was subsequently followed by a noticeable decline in Q1 2022,

raising questions about the sustainability of the initial increase. Meanwhile, print circulation moved along

a remarkably consistent trendline since 2016, with declines showing no signs of acceleration during

the pandemic.

Given the rise of digital and the continuous decline in print circulation, the long‐time circulation gap between

print and digital has narrowed significantly during the pandemic. Nevertheless, for the majority of newspapers

examined in this study, print circulation continues to exceed digital circulation, suggesting that the resilience

of the print product in relation to its digital counterpart, as revealed in previous studies (Chyi & Ng, 2020; Chyi

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

16

& Tenenboim, 2017), has not entirely diminished. However, print circulation at the current level is a cause for

serious concern.

The potential death of newspapers was widely (and wildly) discussed during the 2008 recession (Chyi et al.,

2012), but the current print circulation figures indicate a true existential challenge. Price is a crucial factor.

The substantial industry‐wide price hikes implemented after the recession played a role in the decline in

readership from 2008 to 2016 (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2019). Yet, prices nearly doubled again between 2016

and 2019, undeniably contributing to the continuous declines in print circulation. When a typical print

subscription costs over $1,000 per year, which is on par with the price of the latest iPhone (a device with a

significantly longer lifespan), such a pricing strategy appears unsustainable as it alienates even the most

loyal readers.

While the price of print subscriptions has surged, monetizing online news access remains a challenge. Notably,

the price gap between print and digital subscriptions identified in prior research (Chyi & Ng, 2020) has widened.

Leading the game, The Boston Globe charges $1,347/year for a print subscription while offering its “all digital

access” package at $333 (already the highest digital price among all 18 papers). If price is taken as an indicator

of consumer preference, the price gap between print and digital reaffirms previous research findings that print

and online newspapers coexist not as two normal goods but as a combination of a normal good and an inferior

good (Chyi, 2013; Chyi & Yang, 2009).

Given such a vast price gap, readers’ migration from print to digital would result in substantial losses in

subscription revenue. Digital transformation, from the reader revenue standpoint, is equivalent to “trading

analog dollars for digital dimes” (Zucker, 2009, as cited in Farber, 2013, para. 1). It is also worth noting that

despite these 18 newspapers gaining 290,780 digital subscribers during the pandemic, they lost 544,297

print subscribers, indicating that not everyone who discontinued the increasingly expensive print

subscription turned to the same newspaper’s digital subscription despite a much lower price.

Therefore, these findings serve as a reaffirmation that news consumers are anything but platform‐agnostic

(Chyi & Ng, 2020; Chyi & Tenenboim, 2017; Thurman & Myllylahti, 2009). Despite the narrowing of the

circulation gap as people turned to digital news for various reasons during the pandemic, this did not imply a

fundamental shift in newspaper readers’ preference for the print edition in relation to the same newspaper’s

paid‐for digital product. These results raise a pressing question: In the post‐Covid‐19 era, how should

newspaper firms approach digital transformation when the outcome would further weaken the industry?

6. Limitations and Future Research

The sample comprises 18 metropolitan daily newspapers operating in different newspaper markets across

the US. However, prominent national newspapers, like The New York Times, which is known for successfully

expanding its digital subscriber base, were not included in the sample. This exclusion was due to these

newspapers not providing comprehensive digital data to the AAM (Edmonds, 2021; Pew Research Center,

2023). Nonetheless, The New York Times employs pricing strategies that are no different from those used by

the 18 newspapers studied, that is, significantly increasing the subscription price for its print product while

offering its digital edition at a much lower rate. Therefore, the revenue implications (i.e., exchanging analog

dollars for digital dimes) generated from the findings of this study equally apply to The New York Times or

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

17

other newspapers adopting a similar strategy. However, The New York Times’ national newspaper status

inherently affords it a considerably larger subscriber base.

Another limitation of this study is the lack of access to cost data, as cost reduction is frequently cited as a

major rationale for newspapers’ endeavors toward digital transformation. However, transitioning toward an

all‐digital production could reduce certain variable costs, such as printing and delivery, while major fixed costs,

such as content production, would remain unaffected. With digital accounting for 39–48% of newspapers’

shrinking advertising revenue 2021–2023 (Pew Research Center, 2023) and merely 5% of their subscription

revenue as estimated by this study, the print product remains the primary revenue source.

Research should continue monitoring news consumers’ use, preferences, and willingness to pay for

multiplatform news products. Newspapers must engage in a critical review of their technology‐centric

strategy, reinvesting in content as well as their legacy product, which has served as the lifeblood for

newspapers and likely may continue this role beyond the Covid‐19 era. Time is of the essence as the

industry is running out of opportunities to discover effective solutions.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

Alliance for Audited Media. (2022a). Identifying news media digital replica and nonreplica. https://support.

auditedmedia.com/identifying‐news‐media‐digital‐replica‐and‐nonreplica

Alliance for Audited Media. (2022b). News media circulation terms and definitions. https://support.

auditedmedia.com/news‐media‐circulation‐terms‐and‐definitions

American Press Institute, & ITZBelden. (2009). Online revenue initiatives. http://www.slideshare.net/

Mediatrend/online‐rev2009‐final

Ananny, M., & Bighash, L. (2016). Why drop a paywall? Mapping industry accounts of online news

decommodification. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3359–3380.

Benton, J. (2018, November 1). The New York Times is on pace to earn more than $600 million in digital this year,

halfway to its ambitious goal. Nieman Lab. http://www.niemanlab.org/2018/11/the‐new‐york‐times‐is‐

on‐pace‐to‐earn‐more‐than‐600‐million‐in‐digital‐this‐year‐halfway‐to‐its‐ambitious‐goal

Carlson, D. (2003). The history of online journalism. In K. Kawamoto (Ed.), Digital journalism (pp. 31–55).

Rowman & Littlefield.

Chyi, H. I. (2012). Paying for what? How much? And why (not)? Predictors of paying intent for multiplatform

newspapers. International Journal on Media Management, 14(3), 227–250.

Chyi, H. I. (2013). Trial and error: U.S. newspapers’ digital struggles toward inferiority (Vol. 14). University of

Navarra.

Chyi, H. I., Lewis, S. C., & Zheng, N. (2012). A matter of life and death? Examining how newspapers covered

the newspaper “crisis.” Journalism Studies, 13(3), 305–324.

Chyi, H. I., & Ng, Y. M. M. (2020). Still unwilling to pay: An empirical analysis of 50 U.S. newspapers’ digital

subscription results. Digital Journalism, 8(4), 526–547.

Chyi, H. I., & Tenenboim, O. (2017). Reality check: Multiplatform newspaper readership in the United States,

2007–2015.

Journalism Practice

,

11

(7), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1208056

Chyi, H. I., & Tenenboim, O. (2019). Charging more and wondering why readership declined? A longitudinal

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

18

study of U.S. newspapers’ price hikes, 2008–2016. Journalism Studies, 20(14), 2113–2129. https://doi.org/

10.1080/1461670X.2019.1568903

Chyi, H. I., & Yang, M. J. (2009). Is online news an inferior good? Examining the economic nature of online

news among users. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(3), 594–612.

Doctor, K. (2011, March 7). Nine questions on the Dallas Morning News pay plan. Newsonomics. http://

newsonomics.com/nine‐questions‐on‐the‐dallas‐morning‐news‐pay‐plan

Edmonds, R. (2021, July 21). Newspaper paid digital‐only subscriptions claims and audited numbers

are not in sync. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/business‐work/2021/newspaper‐paid‐digital‐only‐

subscriptions‐claims‐and‐audited‐numbers‐are‐not‐in‐sync

Edmonds, R. (2022, September 15). Traffic to local news websites has plummeted. What happens now?

Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/commentary/2022/local‐news‐website‐pageviews‐down‐2022

Farber, D. (2013, July 23). CNN’s Jeff Zucker trades analog dollars for digital quarters. CNET. https://www.cnet.

com/tech/services‐and‐software/cnns‐jeff‐zucker‐trades‐analog‐dollars‐for‐digital‐quarters/

Herbert, J., & Thurman, N. (2007). Paid content strategies for news websites. Journalism Practice, 1(2),

208–226.

Hoskins, C., McFadyen, S., & Finn, A. (2004). Media economics: Applying economics to new and traditional media.

SAGE.

Hussman, W. E., Jr. (2007, May 7). How to sink a newspaper.

Wall Street Journal

, A15.

Jarvis, J. (2007, September 20). Times deselected. BuzzMachine. http://www.buzzmachine.com/2007/09/17/

times‐deselected

Kim, S. J., Wang, X., & Malthouse, E. C. (2022). Digital news readership and subscription in the United States

during Covid‐19: A longitudinal analysis of Clickstream and subscription data from a local news site. Digital

Journalism, 10(6), 1015–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1984972

Kinsley, M. (2009, February 10). You can’t sell news by the slice. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/

2009/02/10/opinion/10kinsley.html?_r=1&ref=todayspaper

Myllylahti, M. (2014). Newspaper paywalls—The hype and the reality: A study of how paid news content

impacts on media corporation revenues. Digital Journalism, 2(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/

21670811.2013.813214

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters Institute digital news report

2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/

files/2023‐06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf

O’Brien, D., Wellbrock, C.‐M., & Kleer, N. (2020). Content for free? Drivers of past payment, paying intent and

willingness to pay for digital journalism: A systematic literature review. Digital Journalism, 8(5), 643–672.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1770112

Peters, J. W. (2011, March 17). New York Times to impose fees for web readers on March 28. The New York

Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/18/business/media/18times.html

Pew Research Center. (2017, June 1). State of the news media methodology. Pew Research Center’s Journalism

Project. http://www.journalism.org/2017/06/01/state‐of‐the‐news‐media‐methodology

Pew Research Center. (2023, November 10). Newspapers fact sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/

journalism/fact‐sheet/newspapers

Picard, R. G. (2003). Cash cows or entrecôte: Publishing companies and disruptive technologies. Trends in

Communication, 11(2), 127–136.

Picard, R. G. (2008). News consumption and the business of journalism. In New models for news: The 2008

Breaux symposium (pp. 112–118). Louisiana State University.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

19

Picard, R. G. (2014). New approaches to paid digital content. In N. Newman & D. Levy (Eds.), Reuters institute

digital news report 2014: Tracking the future of news (pp. 80–82). University of Oxford.

Picard, R. G., & Brody, J. H. (1997). The newspaper publishing industry. Allyn & Bacon.

Steinbock, D. (2000). Building dynamic capabilities: The Wall Street Journal interactive edition—A successful

online subscription model (1993–2000). International Journal on Media Management, 2(3), 178–194.

Stelter, B. (2017, September 26). Washington Post digital subscriptions soar past 1 million mark. CNNMoney.

http://money.cnn.com/2017/09/26/media/washington‐post‐digital‐subscriptions/index.html

Thurman, N. (2014). Newspaper consumption in the digital age: Measuring multi‐channel audience attention

and brand popularity. Digital Journalism, 2(2), 156–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.818365

Thurman, N. (2017). Newspaper consumption in the mobile age. Journalism Studies, 19(10), 1409–1429.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1279028

Thurman, N., & Myllylahti, M. (2009). Taking the paper out of news: A case study of Taloussanomat, Europe’s

first online‐only newspaper. Journalism Studies, 10(5), 691–708.

Varian, H. R. (2013, September 26). Hal Varian: The economics of the newspaper business. International

Journalism Festival. http://www.journalismfestival.com/news/hal‐varian‐on‐the‐economics‐of‐the‐

newspaper‐business

Williams, A. T. (2016, February 29). Paying for digital news: The rapid adoption and current landscape of

digital subscriptions at U.S. newspapers

. American Press Institute.

https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/

publications/reports/digital‐subscriptions

Windsor, T. (2009, February 10). Will paid content work? Two cautionary tales from 2004. Nieman Journalism

Lab. http://www.niemanlab.org/2009/02/will‐paid‐content‐work‐two‐cautionary‐tales‐from‐2004

About the Authors

Hsiang Iris Chyi is a professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of

Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on the economics of digital journalism, addressing

key issues facing the newspaper industry. Her Ramen Noodles Theory suggests that online

news, like Ramen Noodles, is an inferior good. Her book, Trial and Error: U.S. Newspapers’

Digital Struggles Toward Inferiority, challenges US newspapers’ technology‐centric strategy,

calling for a reassessment of the future of the industry.

Sun Ho Jeong is an assistant professor in the Department of Mass Communication at

Konkuk University, South Korea. Her primary research interests include journalism in

the context of digitization and globalization, and the role of digital media in fostering

social change. She has published in academic journals including Information, Communication

and Society, International Communication Gazette, International Journal of Communication,

Journalism, and Journalism Practice.

Media and Communicaon • 2024 • Volume 12 • Article 7482

20