May 2020

A Cash Flow Perspective on

the Small Business Sector

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

2

Introduction

Diana Farrell

Chris Wheat

Chi Mac

The small business sector is fre-

quently lauded for its contributions

to the U.S. economy. A thriving small

business sector is an indicator of a

strong economy, given the outsized

contributions to job creation that

certain innovative and entrepreneurial

small businesses make, though in an

economic downturn like the current

COVID-19 pandemic, the sector may

sustain the greatest job losses. In 2016,

firms with fewer than 500 employees

made up more than 99 percent of all

businesses in the U.S., and these firms

were responsible for nearly half of all

net new jobs.

1

In particular, a minority

of very fast growing firms have drawn

the attention of researchers by creat-

ing the majority of new jobs (Birch and

Medo, 1994; Audretsch, 2012). These

high-growth firms are identifiable

from their early behavior (Guzman and

Stern, 2016) and continue to distin-

guish themselves from other small

businesses over time (Pugsley, 2018).

While job creation is an important

outcome, it is not the only way that

small businesses contribute to the real

economy. Other than the jobs created

for their owners, job creation fails to

capture the economic contributions

of the 25 million small businesses

with no employees at all. All small

businesses sell goods and services

and procure the inputs needed to

produce those goods and services. The

revenues, expenses, and other cash

flows associated with this economic

activity provide an alternative lens on

the sector and its broader contribution

to economic vitality and growth. In

addition, a high-frequency lens on

revenue, expenses, and financial

flows provides a new opportunity to

understand how small businesses

manage cash-flow challenges while

attempting to survive and grow.

Over the past five years the

JPMorgan Chase Institute has

explored the financial lives of U.S.

small businesses through the lens

of de-identified transaction and

account summary data from over 1

million small businesses with a Chase

business deposit account.

2

These data

correspond to the universe of both

employer and nonemployer businesses,

and provide unprecedented views of

high-frequency cash flows in the small

business sector. Through answering

questions about how small businesses

contribute both to aggregate and

broad-based U.S. economic growth,

these analyses have generated three

consistent and cross-cutting insights:

• The small business sector makes

impor

tant contributions to the

real economy through revenue

generation and revenue growth.

• Small businesses operate in an

en

vironment of irregular cash flows

against limited cash liquidity.

• While small businesses have

the poten

tial to contribute to

broad-based growth, mean-

ingful dierences in outcomes

by owner gender, age, and

community characteristics limit

the contributions and resilience

of many firms in the sector.

A thriving small

business sector is

an indicator of a strong

economy, but the sector

can also be severely

impacted by economic

downturns.

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

3

Small Business Revenue

Generation and Growth

A first insight from financial transac-

tions data is that all small businesses,

employer or not, have the ability to

deliver economic gains to broad and

diverse segments of the U.S. economy.

Revenue generation is the foundation

for this growth and dynamism, allow-

ing small businesses to cover expenses

and provide a livelihood for owners

and their families. Revenue growth is

often an indicator of small business

financial health, and given the sheer

number of small businesses, even

modest increases in revenue gener-

ation and growth could have a large

eect on the economy and improve

the financial well-being of tens of

millions of small business owners.

The breadth of these contributions can

be obscured by a homogenous view of

the sector as comprised principally by

employer businesses, or technology-

intensive firms that grow through

external finance. In fact, the full small

business sector contains substantial

heterogeneity. Several observers have

proposed segmentations of the sector

that identify the distinctive contri-

butions of dierent small business

segments to the economy (Birch and

Medo, 1994; Mills, 2015; Farrell and

Wheat, 2017a). While these segments

dier in their contributions to the

economy, liquidity and the manage-

ment of cash flows are core issues to

businesses seeking to grow as well

as those simply seeking to survive.

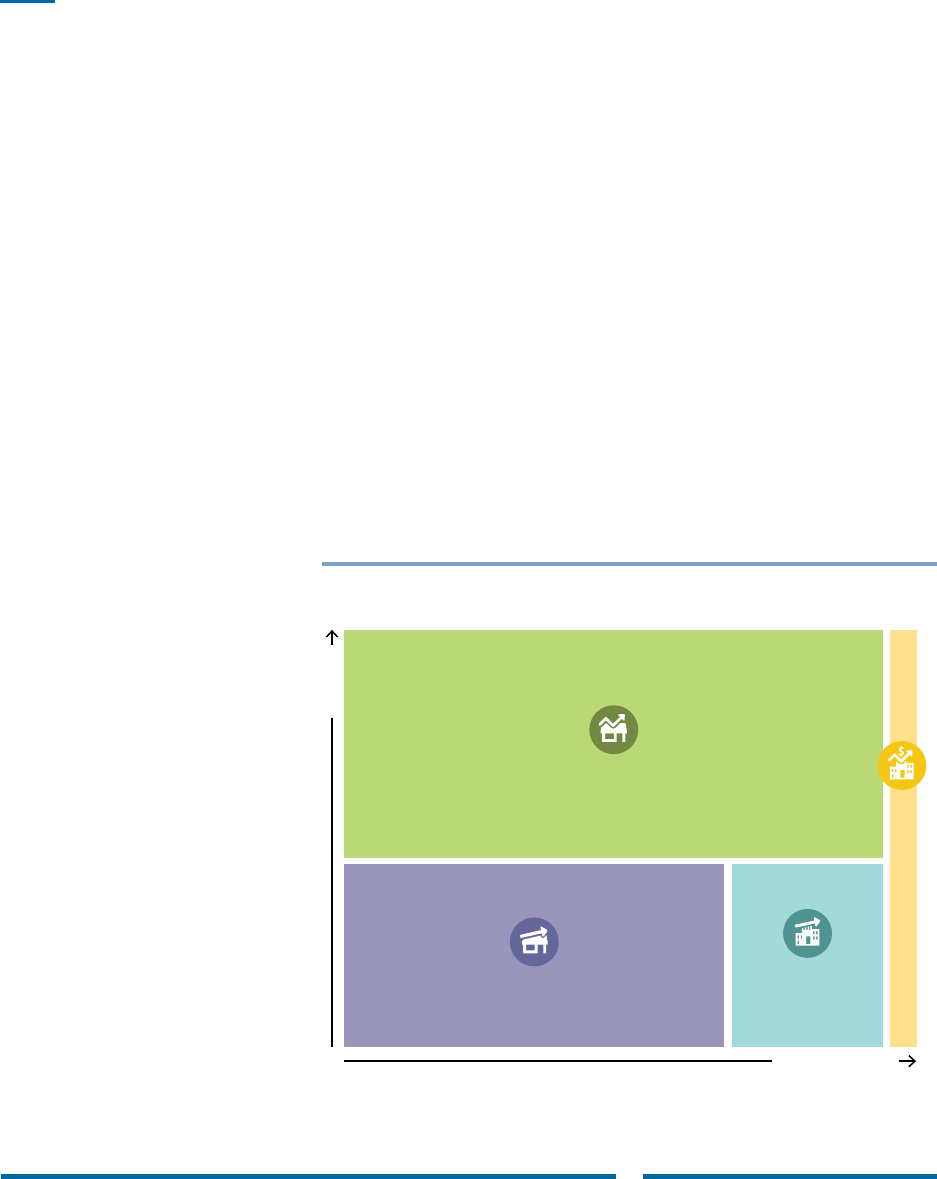

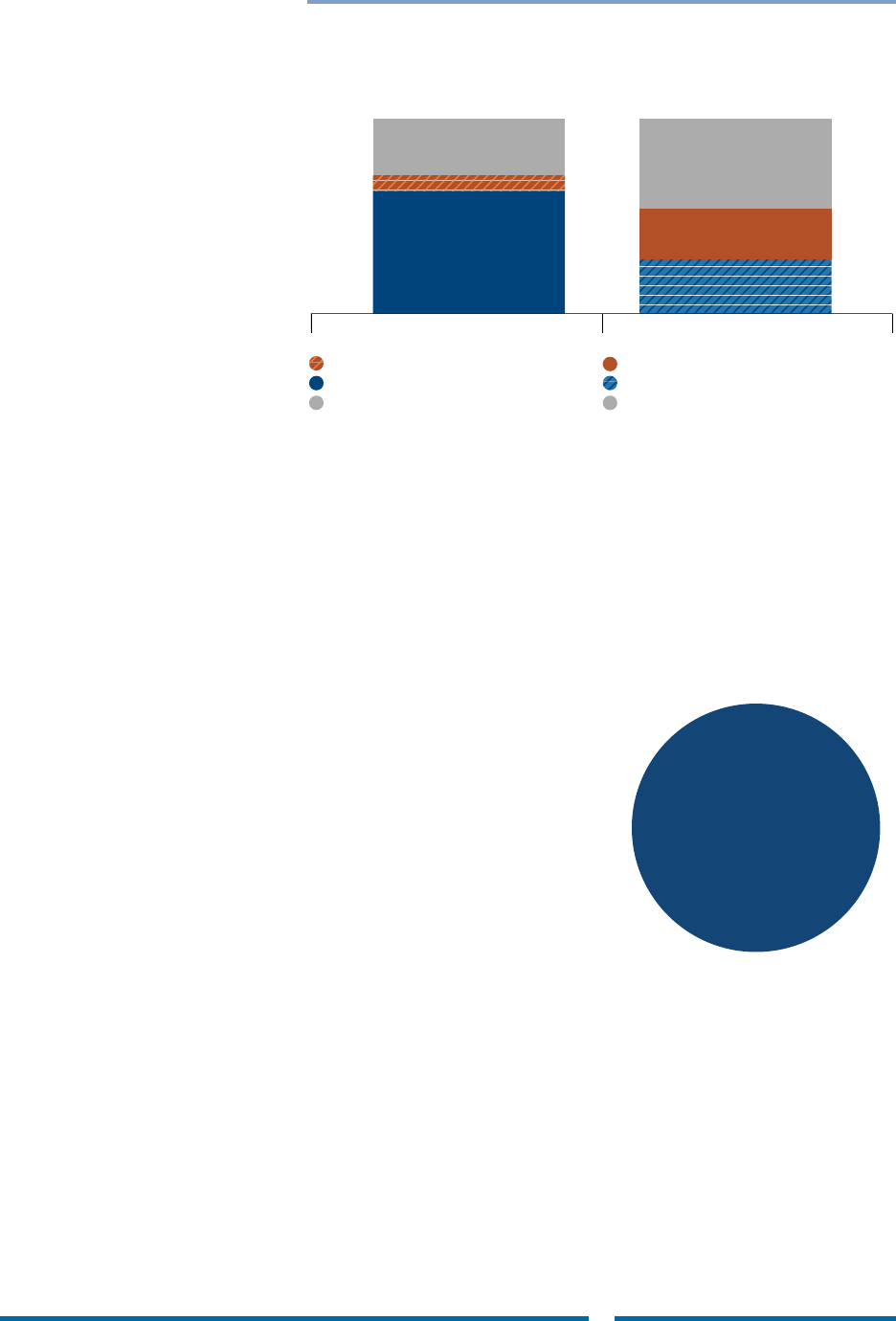

In order to place the revenue gener-

ation contributions of businesses in

context, Figure 1 presents a segmen-

tation of the small business sector

framed in terms of the dimensions of

growth, complexity, and dynamism

(see Box 1 for details of segment

definitions). Small stable employers and

financing-intensive small businesses

with the potential for dramatic growth

make important contributions to the

economy, but only comprise 4 and

3 percent of new firms in our data,

respectively. The other 93 percent

of new businesses in our sample do

not fall in either of these categories,

and are businesses less likely to be

observed by using employment records

and/or by seeking to identify high-

growth businesses. Data on financial

transactions show that, contrary to the

often-held belief that firms that grow

using external finance contribute the

most to the economy, organic growth

firms make substantial contributions

in terms of their prevalence, revenue

generation, and employment. The

left panel of Figure 2 shows that over

their first four years, organic growth

firms were the most common type of

firm with 54 percent of first-year firms

falling within the segment. Organic

growth firms also abound across

industries and local economies. Even

in San Francisco—a city well-known

for financed high-tech firms—organic

growth firms comprised 52 percent of

new small firms (Farrell et al., 2018).

Figure 1: A segmentation of the small business sector

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Dynamism

Size and complexity

Stable micro

Organic growth

Financed growth

Stable small

employer

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

4

Box 1: Segment Definitions

Financed Growth

These firms engage in financial behaviors

consistent with the intention to make early

investments in assets that would serve as the basis for a

scale-based competitive advantage (e.g., investments in

technology, brand, learning curve, or customer net-

works). Specifically, we identify a firm as a member of

the financed growth segment if it has at least $400,000

in financing cash inflows during its first year—a level

consistent with financing amounts used by small

businesses that take in investment capital.

Organic Growth

Firms in this segment also have growth

intentions, but they primarily attain that

growth organically out of operating profits rather than

through the use of external financing. In order to capture

both firms that intend to grow and succeed and those that

intend to grow but fail, we leverage post hoc observations

of revenue growth and define this segment as those firms

with less than $400,000 in financing cash inflows in their

first year that either achieve average revenue growth of

at least 20 percent per year from their first year to their

fourth year, or those that see revenue declines of at least

20 percent per year. We also include firms that exit prior to

four years that average above 20 percent revenue growth

or 20 percent revenue declines per year prior to exit.

Stable Small Employers

Firms in this segment are less dynamic:

they are in neither the financed growth nor

the organic growth segments and likely have a stable

growth strategy and a business model premised on the

employment of others. We define stable small employers

as those firms that have electronic payroll outflows in

six months or more of their first year. To capture larger

small employers who do not use electronic payroll, we

also include firms that have over $500,000 in expenses

in their first year—approximately equivalent to payroll

expenses for ten employees—in this segment.

Stable Micro Businesses

Firms in this segment have either no or

very few employees and do not exhibit

behaviors consistent with growth intentions. We define

the stable micro segment as containing those busi-

nesses that do not have electronic payroll outflows

for six months of their first year and have less than

$500,000 in expenses.

Figure 2: Organic growth firms contribute the majority of small business revenue four years after founding

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

54%

11%

55%

38%

51%

3%

4%

21%

22%

4%

29%

5%

36%

17%

17%

14%

14%

Year 1

Year 4

Year 1

Year 4

Number of firms Aggregate revenue

n = 138,026

n = 93,137

33% of all

firms exit

31%

of organic growth firms exit

15%

of stable micro firms exit

12%

of stable small employer firms exit

20%

of financed growth firms exit

Aggregate revenue

increases 20%

Exits before two years

Organic growth

Financed growth

Stable micro

Stable small employer

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

5

Perhaps even more surprisingly,

organic growth firms generate the

majority of aggregate revenue, the

overwhelming majority of aggregate

revenue growth, and even the majority

of payroll dollars over these first four

years. The right panel of Figure 2

shows that organic growth firms

generated 51 percent of aggregate

revenue. They make even larger contri-

butions to aggregate revenue growth.

Organic growth firms were over-

whelmingly the largest contributors

to aggregate revenue growth in each

of the twenty-five cities we analyzed

(Farrell and Wheat, 2019). Moreover,

while most organic growth firms were

nonemployers, by their fourth year

55 percent of employer firms had

grown organically, and these firms

generated 52 percent of aggregate

payroll dollars (Farrell et al., 2018).

Businesses that

grow organically

out of operating profits

generate the majority of

small business revenue

and payroll.

The economic contributions of small

businesses through revenue are

especially important given the relative

stability of employer status. The

stability of employer status is import-

ant because, as other researchers have

observed, the creation of a single job

by a large fraction of microbusinesses

could have a material impact on net

job creation (e.g., JPMC and ICIC,

2016) and a number of recent policy

proposals have drawn attention to

the possibility of generating inclusive

and broad-based economic growth

through increased employment in the

small business sector. Our data show

that it is decidedly more likely for

nonemployer businesses to exit than to

add employees to their payroll. In each

of their first four years, only 2 percent

of nonemployers added employees,

while 33 percent exited by their fourth

year. Additionally, for the first ten

years, the exit rate for nonemployer

businesses at each age was more

than five times higher than the rate at

which nonemployers become employer

businesses (Farrell et al., 2018).

3

After their first year of employment,

small businesses actually lose more

jobs than they create, principally

through firm failure. For every

100 small business jobs, new small

businesses created 5.6 new jobs,

while existing small businesses lost

3.9 jobs—mostly due to losses from

the exit of these small businesses.

In many cases, employer small

businesses also have to contend with

volatile changes in payroll, which

can have adverse eects. Most small

employer businesses experience

unstable payroll and employment

volatility including job gains and

losses and other spikes and dips in

payroll (Farrell and Wheat, 2017b).

Our data uniquely document the con-

tributions of smaller small businesses

for whom the cash-flow lens is more

important than the employment

lens, and highlights the importance

of revenue generation and growth.

Nonemployer small businesses make

up the majority of the sector and

while they are unlikely to transition to

employer status, they are nevertheless

important when viewed through other

lenses of economic growth. Also,

while high-growth success stories

deserve to be celebrated, they are

rare. Most small businesses do not

achieve and may not even attempt

to achieve this type of success, but

they nevertheless produce large

shares of small business revenue,

especially in their first few years.

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

6

Limited Buers and

Irregular Cash Flows

All small businesses, regardless of

industry or segment, must manage

their cash flows in order to survive and

grow. Unless revenues and expenses

are perfectly coordinated, small

businesses need access to sucient

funds in order to purchase the inputs

required to deliver those goods and

services. Maintaining cash balances is

one approach to address challenges

related to the irregularity of cash

flows such as these. This potential for

mismatched revenues and expenses

leads to three key questions:

1. Is it c

ommon for small busi-

nesses revenues, expenses,

and financial transactions to

occur in irregular patterns that

may be dicult to predict?

2. Do small businesses carry

liquidit

y consummate with the

irregularity of their cash flows?

3. Can small businesses weather

irregularities in cash flows?

To answ

er the first question, we first

turned to measuring the regularity of

small business cash flows from deposit

transaction data (See Farrell et al., 2018

for details). Revenues and expenses

may be irregular in their dollar amounts

and/or their timing. For example, a firm

oering a single product might always

receive a fixed dollar amount for each

sale, but could generate these sales

at varying and perhaps unpredictable

intervals. Alternatively, a firm providing

a weekly service could generate sales

on a regular weekly cadence, but

with wide variation in dollar amounts.

Through this lens, few small businesses

have very regular cash-flow patterns,

and some have less regular patterns

than others (Farrell et al., 2018).

Employer small businesses, while

making material contributions to the

economy through job creation, may be

especially exposed to irregular cash

flows. Among small businesses with

electronic payroll outflows, 61.8 percent

had unstable payroll outflows over a

year, driven either by sustained gains or

losses in employment, or perhaps less

predictably, spikes or dips in employ-

ment levels (Farrell and Wheat, 2017).

While many small businesses have

irregular cash flows, even more have

limited cash liquidity. In principle, a

small business might be able to manage

irregular cash flows by holding a “cash

buer” that allows it to operate without

interruption in the event of a revenue

disruption or major expense. We

operationalize this idea by calculating

the average number of cash buer days

held by small businesses by dividing

the average daily cash balance by the

average daily cash outflows (Farrell and

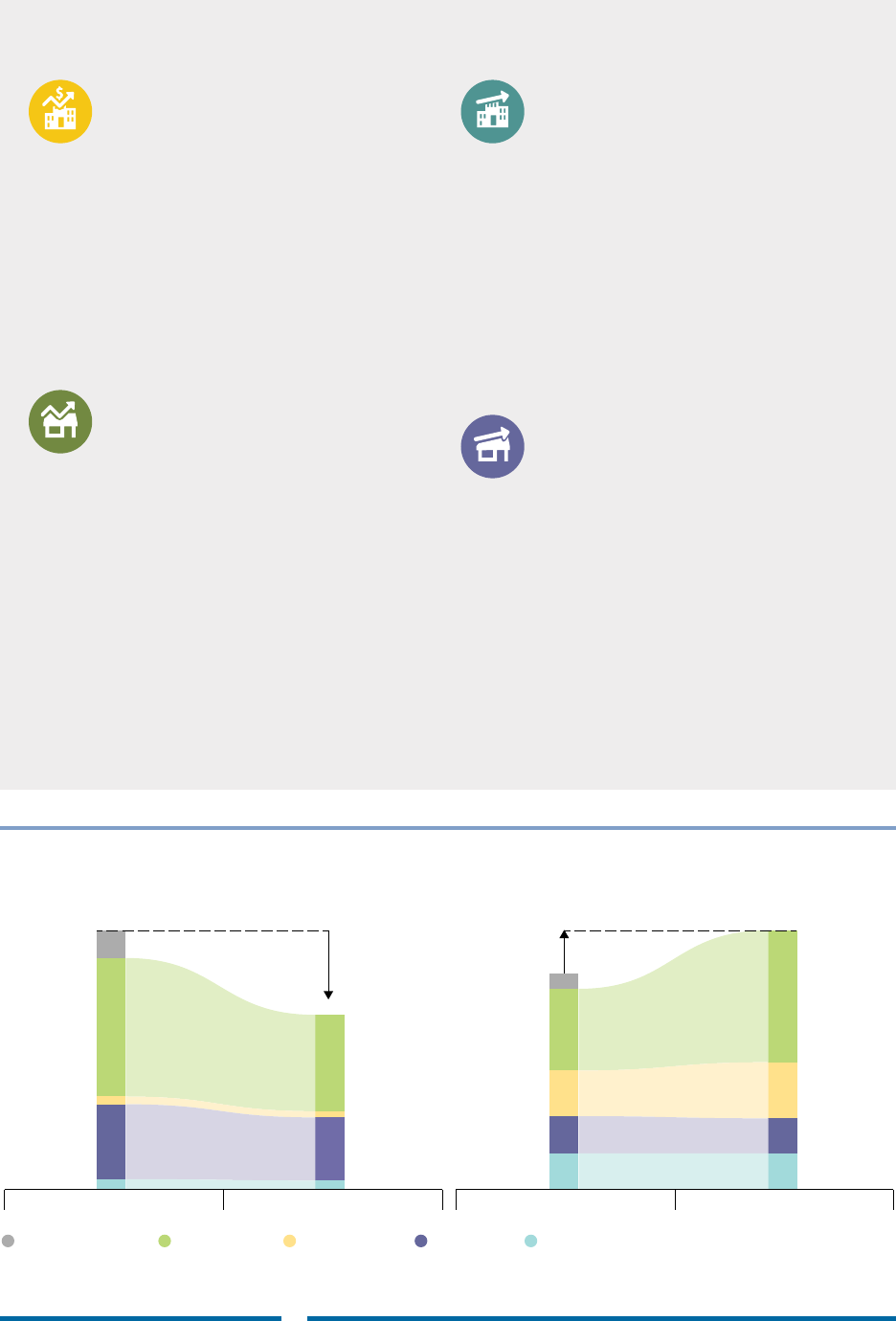

Wheat, 2016). As shown in Figure 3, 50

percent of small businesses had fewer

than fifteen cash buer days (Farrell

et al., 2019b), and only 40 percent

had more than three weeks. Small

business cash buers vary substantially

across local economies—the median

small business in San Francisco, San

Jose, and Seattle has eighteen cash

buer days, more than 60 percent

higher than the eleven cash buer

days held in reserve by the median

business in Atlanta and Orlando.

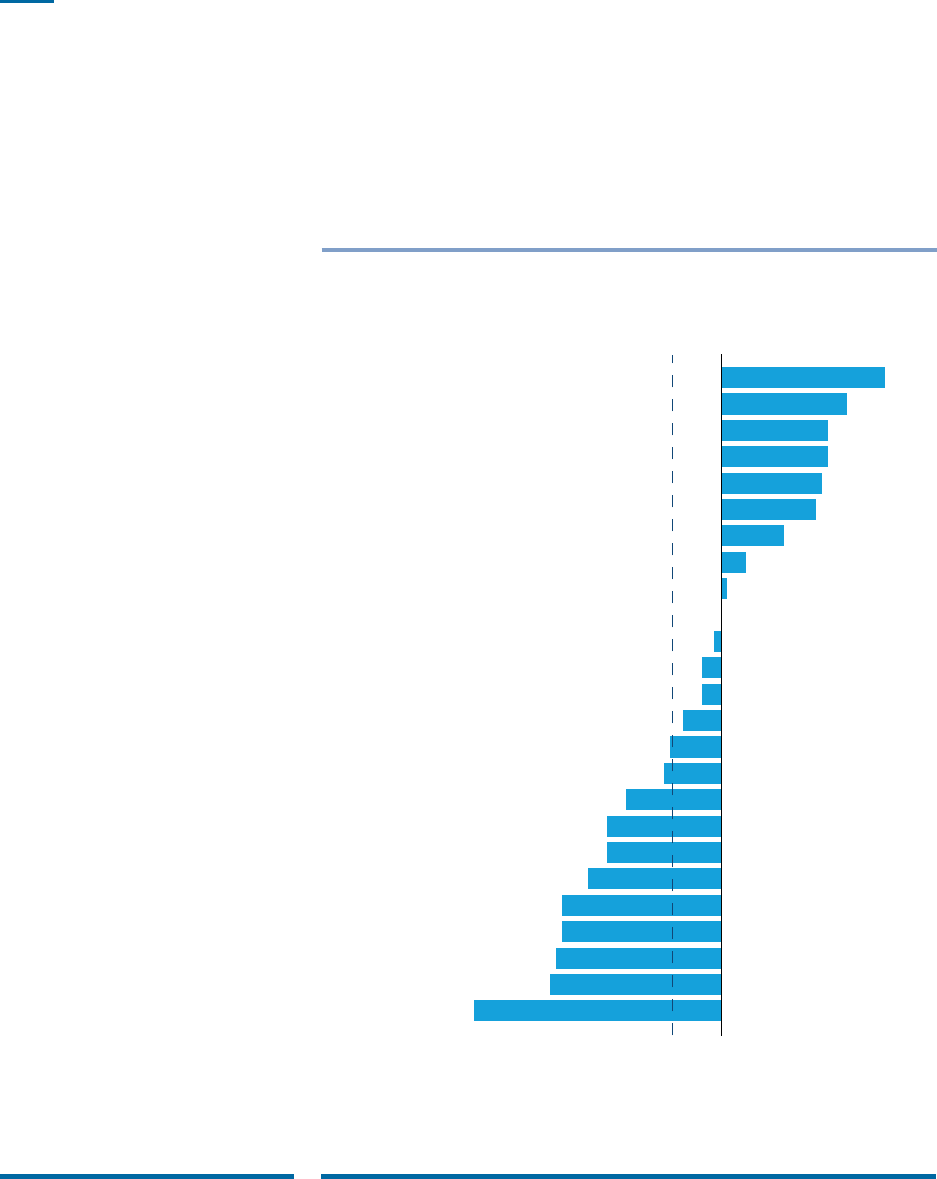

Figure 3: Many small businesses have limited cash liquidity

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Median cash buffer days: 15

Cash buffer days

0

60

100

20

40

80

Note: Cash buffer days mesasured from 2013 to 2017 in the cross sectional sample.

50% of small businesses had

fewer than 15 cash buffer days

Distribution of cash buffer days in 25 metro areas

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

7

A combination of relatively thin

cash buers and irregular cash-flow

patterns could pose a threat to the

survival of small businesses. All

else equal, small businesses with

larger cash buers are more likely

to survive—in the first year, each

additional cash buer day reduces

the likelihood of an exit in the next

year (Farrell et al., 2019a). Moreover,

over their first four years, small

businesses either transition from less

regular cash-flow patterns to more

regular patterns, or exit the market.

As depicted in Figure 4, firms with

irregular cash flows were nearly twice

as likely to exit as those with regular

cash flows. Moreover, those that

transitioned to more regular cash-flow

patterns have faster revenue growth.

Figure 4: Firms with irregular cash flows are nearly twice as likely to exit as

those with regular cash flows

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Note: Cash-flow pattern and industry measured in year two and firm outcome measured in year four. Sample

includes all firms founded in 2013.

Firm outcomes by cash-flow pattern regularity, cohort sample

63%

8%

29%

Regular cash flows Irregular cash flows

28%

26%

46%

Became irregular

Remained regular

Exited

Remained irregular

Became regular

Exited

While these observations suggest

that small businesses would find

it dicult to manage consistently

irregular revenues and expenses,

real-world evidence shows that they

may be surprisingly resilient when

faced with short-term disruptions. For

instance, after Hurricane Harvey hit

Houston, Texas on August 25, 2017,

and Hurricane Irma hit Miami, Florida

on September 10, 2017, the cash

balances of typical small businesses

declined by just under 8 percent.

These declines were the combined

result of drops in revenue by 63

percent and 82 percent in Houston and

Miami, respectively, partially oset

by corresponding drops of 54 percent

and 62 percent in expenses. These

disruptions were short-lived: twelve

days after they reached their lowest

point, cash inflows again showed

increases compared to the previous

year in that same period. By four

weeks after landfall, few businesses

appeared to suer continued cash-

flow impacts directly related to the

storms (Farrell and Wheat, 2018).

While our data do not directly speak

to whether expenses decreased due to

overt actions on the part of business

owners or due to circumstance (e.g.,

hourly workers not being paid while

the business could not open), the

reduced expenses protected the

business until revenues returned to

their prior levels. Further research

is needed to better understand

whether small businesses are equally

resilient in the face of longer-term

irregularities in cash flows.

Small

businesses with

larger cash buers

are more likely

to survive.

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

8

Broad-Based Economic

Growth and Resilience

In recent years, there has been

increasing evidence about the wide

and growing variation of economic

performance across communities

in the United States, as well as

dierences in small business financial

outcomes by owner gender, race,

age, and other demographic charac-

teristics. This variation is reflected

in the resilience and consistent

economic contributions of some

cities, communities, and businesses,

and the vulnerability and more

modest economic contributions of

others. These dierences can limit

the otherwise strong potential of

the sector to contribute to broad-

based growth in a strong economy,

and disproportionally impact some

businesses, owners, and commu-

nities in an economic downturn.

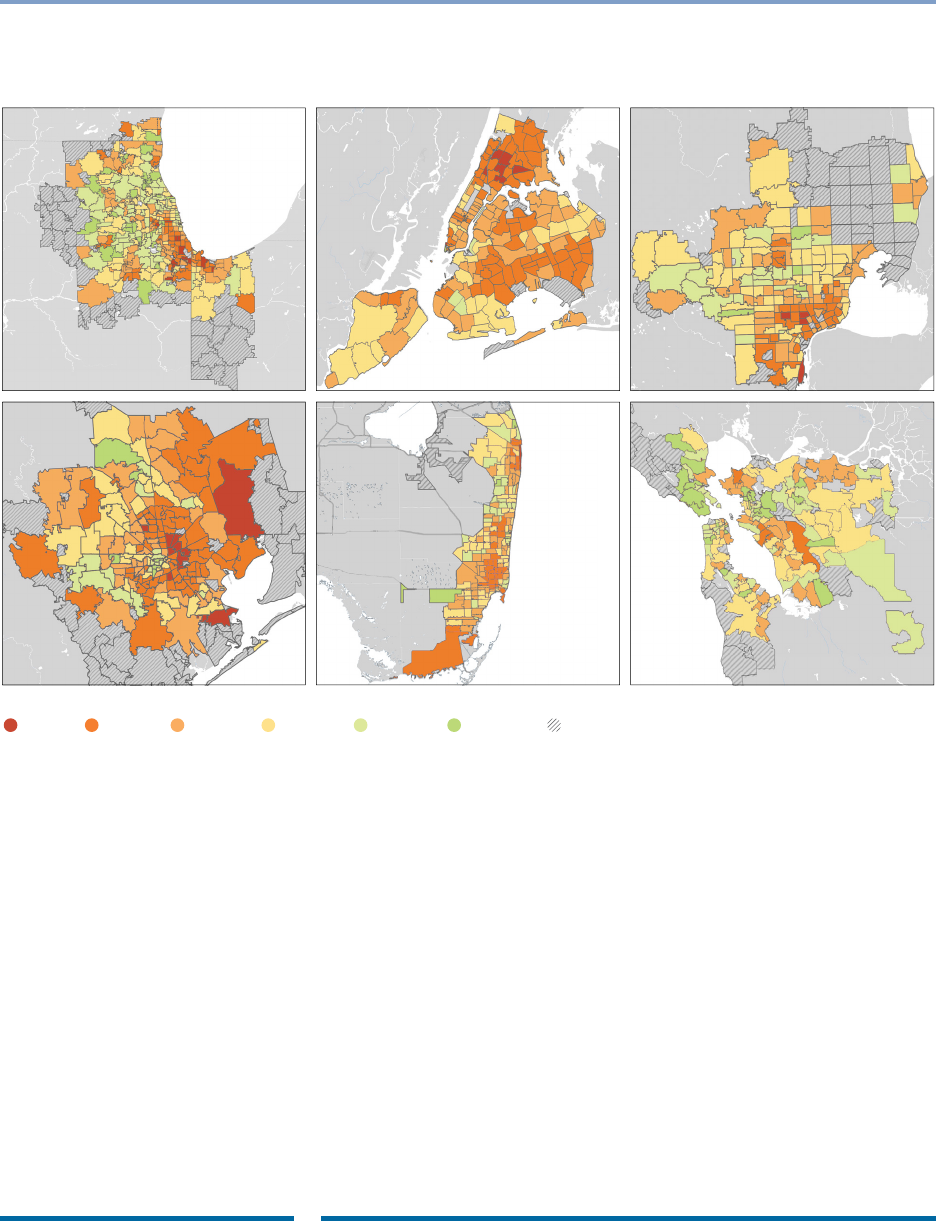

First, the economic contributions of

the small business sector vary widely

by city and region. Figure 5 shows

that aggregate revenue growth varies

especially sharply across cities. The

aggregate revenue of small busi-

nesses operating in cities like San

Francisco and Portland grew 2 per-

cent or more annually over a period

of four years, while the small business

sector in places like Houston and

Sacramento experienced aggregate

revenue declines of 2.5 percent or

more per year over this same period

(Farrell and Wheat, 2019). There are

also dierences across cities in which

industries contribute the most to

growth. The construction industry

is the largest overall contributor to

aggregate revenue growth, and is

the largest contributor in eleven of

the twenty-five cities we analyzed.

Also, contrary to a common belief

that technology-intensive firms

are the primary drivers of growth,

among small businesses, high-tech

services firms were the largest

contributors to growth in only San

Antonio, Seattle, and Tampa.

Figure 5: Aggregate small business revenue growth varies widely across cities

-3.9%

-2.7%

-2.6%

-2.5%

-2.5%

-2.1%

-1.8%

-1.8%

-1.5%

-0.9%

-0.8%

-0.6%

-0.3%

-0.3%

-0.1%

0.1%

0.4%

1.0%

1.5%

1.6%

1.7%

1.7%

2.0%

2.6%

Annualized revenue growth rate for small business

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Average:

-0.76%

Indianapolis

Sacramento

San Antonio

Houston

Detroit

New Orleans

Tampa

Miami

San Diego

Orlando

New York

Phoenix

Los Angeles

Austin

Las Vegas

Dallas

Atlanta

Chicago

Seattle

Riverside

Denver

Columbus

San Jose

Portland

San Francisco

Note: Aggregate revenue growth reflects annualized growth rate from 2013 to 2017.

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

9

While dierences in the ability of small

businesses to thrive and contribute

varies across cities and regions, small

business financial outcomes vary even

more between neighborhoods within a

city. An important factor that enables

the resilience of small businesses in

the face of uncertainty is cash liquidity.

Accordingly, the wide variation we

observe in small business cash liquidity

across communities is especially

concerning (Farrell et al., 2019b).

Small businesses in majority-Black or

majority-Hispanic communities have

significantly lower cash liquidity than

businesses in majority-White communi-

ties. As shown in Figure 6, in 89 percent

of majority-Hispanic communities

and 95 percent of majority-Black

communities, most small businesses

operated with a cash buer of

two weeks or less, as compared to

about 30 percent of majority-White

communities and only 2.3 percent of

majority-Asian communities. Small

businesses in communities with low

home values or few college gradu-

ates also have less cash liquidity.

Dierences in

the ability of small

businesses to thrive

and contribute varies

across cities and

communities.

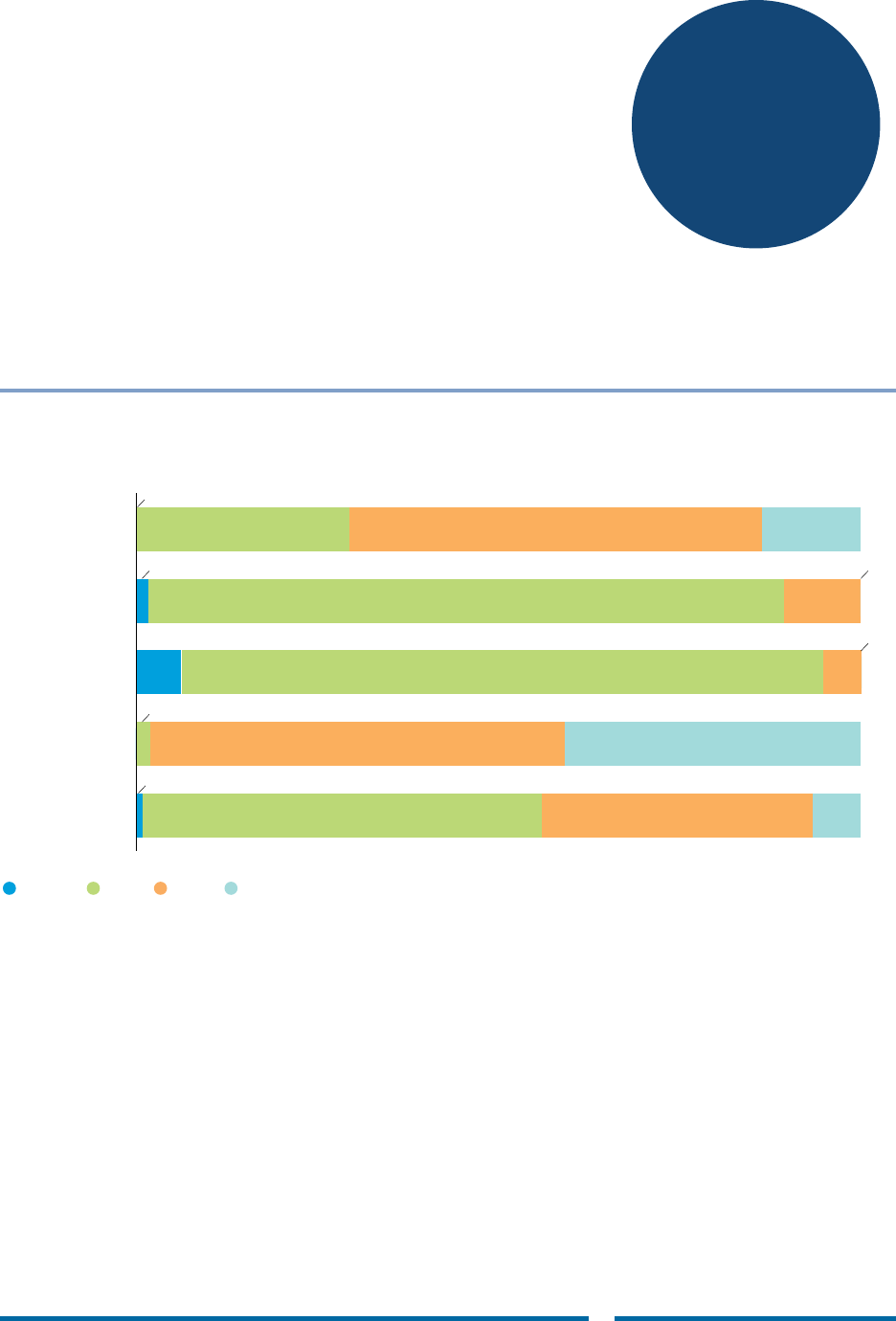

Figure 6: Small businesses with large cash buers are rare in majority-Black and majority-Hispanic communities

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute, US Census Bureau

Under 7

7–14

14–21

Over 21

0.9%

6.3%

1.7%

0.2%

55.1%

2.0%

88.5%

87.7 %

29.3%

37.3%

57.1%

5.3%

10.5%

56.9%

6.7%

40.8%

0.0%

13.5%

All other communities

Majority-Asian

Majority-Black

Majority-Hispanic

Majority-White

Median cash buffer days by ZIP code racial composition

0.0%

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

10

Moreover, small businesses in

majority-Black and majority-Hispanic

communities and communities with

lower home values and few college

graduates also generate lower

profits. Figure 7 presents the median

profit margin for communities in the

Chicago, Detroit, Houston, Miami, New

York, and San Francisco metro areas

(Farrell et al., 2019b). In each metro

area, there are large contiguous areas

in which most small businesses had

low profit margins. In contrast, there

are large areas where most small

businesses were quite profitable.

Figure 7: Profitability varies substantially within metropolitan areas

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Median profit margin for ZIP codes in Chicago, Detroit, Houston, Miami, New York, and San Francisco metro areas, 2013-2017

0–5%

5–10%

10–15%

15–20%

20–25%

25–100%

No data

Chicago Metro

Area

New York City

Detroit Metro

Area

Houston

Metro Area

Miami Metro Area

San Francisco Metro Area

In addition to the place in which a

small business is located, the age

and gender of the business owner

can have an important impact on

its financial well-being, its ability to

contribute to broad-based growth, and

its exposure to economic downturns.

The demographic characteristics of

owners of the smallest businesses are

generally more similar to the overall

demographics of the U.S. than those

of larger businesses.

4

Accordingly,

the smallest small businesses—par-

ticularly nonemployer and very small

employer businesses—may be best

positioned to deliver broad-based

economic growth, or most vulner-

able to negative economic shocks.

Moreover, the financial lives of these

small businesses are deeply inter-

twined with the financial lives of their

owners. As a result, understanding

variation in financial outcomes by

owner demographics can inform the

extent to which the sector as a whole

is delivering broad-based economic

growth to the substantial share of U.S.

families that own small businesses,

or how impacts to the small business

sector distribute across the economy.

A first observation concerns the distri-

bution of small business segments by

gender and age. In general, financed

growth firms are concentrated in a

relatively small number of industries

and geographic locations, while

organic growth firms are much more

evenly distributed (Farrell et al.,

2018). We find a similar pattern in

the distribution of these segments by

gender and age, as shown in Figure 8.

Women-owned small businesses

and small businesses with younger

owners are underrepresented among

financed growth firms, but have shares

of organic growth businesses that

are quite close to their overall share

of business ownership in our data.

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

11

However, despite their representative

presence among organic growth firms,

a business founded by a woman starts

smaller than a corresponding business

founded by a man, and grows more

slowly. Figure 9 shows that median

first-year revenues among firms owned

by women are $50,000, compared to

$75,000 for ones owned by men, a 34

percent dierence. Among new and

young businesses, revenue growth

is slightly but significantly lower for

firms founded by women, compared to

those founded by men (Farrell et al.,

2019a). Starting with lower revenues

and growing more slowly results in

smaller businesses—by year four, the

typical business owned by a woman

has revenues of $68,000 compared to

$104,000 for one owned by a man.

While the small business sector has

the potential to drive both aggregate

and broad-based economic growth, its

heterogeneity can present challenges.

Dierences in owner age and gender,

employer status, and other factors

could all aect firm growth trajectories

and influence which policy levers to

pull for maximum impact. Additionally,

city- and community-level dierences

in the financial health of the small

business sector have implications

for the national economy as well.

A business

founded by a

woman starts smaller

than a corresponding

business founded by

a man, and grows

more slowly.

Figure 8: Women and younger small business owners are well-represented

among organic growth firms, but underrepresented among financed growth firms

Female

Male

55 and over

35–54

Under 35

Gender

Age group

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Stable micro

Stable small employer

Organic growth

Financed growth

All single-owner

firms in cohort

Stable micro

Stable small employer

Organic growth

Financed growth

All firms in cohort

31%

24%

33%

23%

27%

54%

58%

53%

58%

53%

16%

18%

14%

19%

19%

29%

18%

23%

29%

31%

82%

69%

77%

71%

71%

Figure 9: Businesses founded by women have lower revenues in each of their

first four years

Median revenues for small businesses in 2013 cohort

Female

Male

All firms in cohort

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Note: “All firms in cohort” includes businesses with multiple owners.

Year 4

Year 3

Year 2

Year 1

$75K

$90K

$98K

$104K

$75K

$91K

$100K

$105K

$50K

$59K

$65K

$68K

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

12

Conclusions and

Implications

A lens on small business cash flows

provides a new perspective on the

small business sector that more

broadly captures its impact on both

aggregate and broad-based growth

in the U.S. economy. By capturing a

wide range of small businesses, our

data show the economic contributions

of both employer and nonemployer

businesses, and shed light on new seg-

ments and financial phenomena that

might otherwise be dicult to observe.

These data paint a picture of a sector

that contains an impactful segment

of businesses that grow organically,

in which businesses manage irregular

cash flows with limited cash liquidity,

and show promising outcomes in

terms of broad-based growth while

persistent challenges remain.

Accordingly, policymakers seeking to

drive overall economic growth in the

sector should consider this level of

heterogeneity. Specifically, programs

and policies might target the specific

financing needs of firms that grow

organically in addition to those that

grow with external finance. Firms that

grow organically generate the majority

of revenue, payroll dollars, and an

overwhelming majority of aggregate

revenue growth during their first

few years. These small businesses

may have dierent financing needs

as compared to those who leverage

substantial amounts of external

finance in their first year, including,

but not limited to, short-term working

capital. These financial solutions may

be especially relevant given the prev-

alence of irregular cash-flow patterns

across the sector. Policymakers might

use these irregular cash-flow patterns

to structure policies and programs

that might assist small businesses

with cash-flow management, and

tailor these policies and programs

to the specific challenges faced by

dierent kinds of small businesses.

Policies that boost cash liquidity and

support small businesses in developing

and maintaining a cash buer may

allow firms to better weather finan-

cial shocks. In the face of COVID-19,

for example, revenue losses could

cause more small businesses to shut

down, particularly those with more

limited cash liquidity. Policymakers

can consider increasing liquidity

for small business owners through

grants and loans during economic

downturns and periods of uncertain

demand. Additional targeting of

these programs to majority-Black

and majority-Hispanic communities,

communities with lower amounts

of human and financial capital, and

businesses with irregular cash flows

could help to bolster the most aected.

Policymakers seeking to drive

broad-based growth might also attend

to important dierences in small

business outcomes by business owner

gender and age. In many cases, the

financial fates of small businesses

and their owners are tightly coupled.

In this sense, dierences in small

business outcomes that track owner

demographic characteristics can

generate dierences in household

financial well-being along similar

lines. While growth opportunities

aorded by organic growth businesses

may be evenly distributed by age

and gender, businesses founded by

women start with lower revenues and

experience slower revenue growth.

Moreover, most revenue gains are

concentrated in a small minority of

firms. These dierences in outcomes

suggest that policies that target

small businesses on the basis of

the age and gender of their owners

may help ensure that growth in the

sector impacts the widest range of

businesses, owners, and households.

The wide variation in profitability and

liquidity of small businesses across

cities and communities also highlights

the potential for place-based policies

that recognize the characteristics of

communities and the relationship

between a community and the city

in which it is located. Broad-based

economic growth may benefit from

place-based small business economic

development programs, since the

ability of the sector to deliver a

potential pathway to economic growth

for entrepreneurs from all walks of

life in a broad-based way appears

inconsistent with the substantial

dierences we find between communi-

ties in small business financial health.

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

13

Appendix

A key advantage of high-frequency

cash flow transactional data is that

it provides a granular view of the

specific patterning of small business

cash flows. We use these data to

empirically characterize the kinds of

cash-flow management challenges

small businesses face by developing

four quantitative measures: three that

measure the irregularity of cash flows

with respect to amounts and timing—

volatility, frequency, and consistency—

and one that measures the extent

of financing use. Volatility describes

the extent to which cash flows vary

significantly in their daily total dollar

amounts, frequency describes the

typical schedule of sizeable cash flows,

and consistency describes how often

the timing of large cash flows varies

from its central tendency. Financial

utilization measures the extent to

which cash inflows are mostly financial

inflows rather than revenues.

For each firm in our sample, we

determined the volatility, frequency,

and consistency of both revenues

and expenses, and also the extent

of external finance usage. Based on

these measurements, we identified

seven distinct clusters that captured

the typical patterns of cash-flow

irregularities we observed in our data.

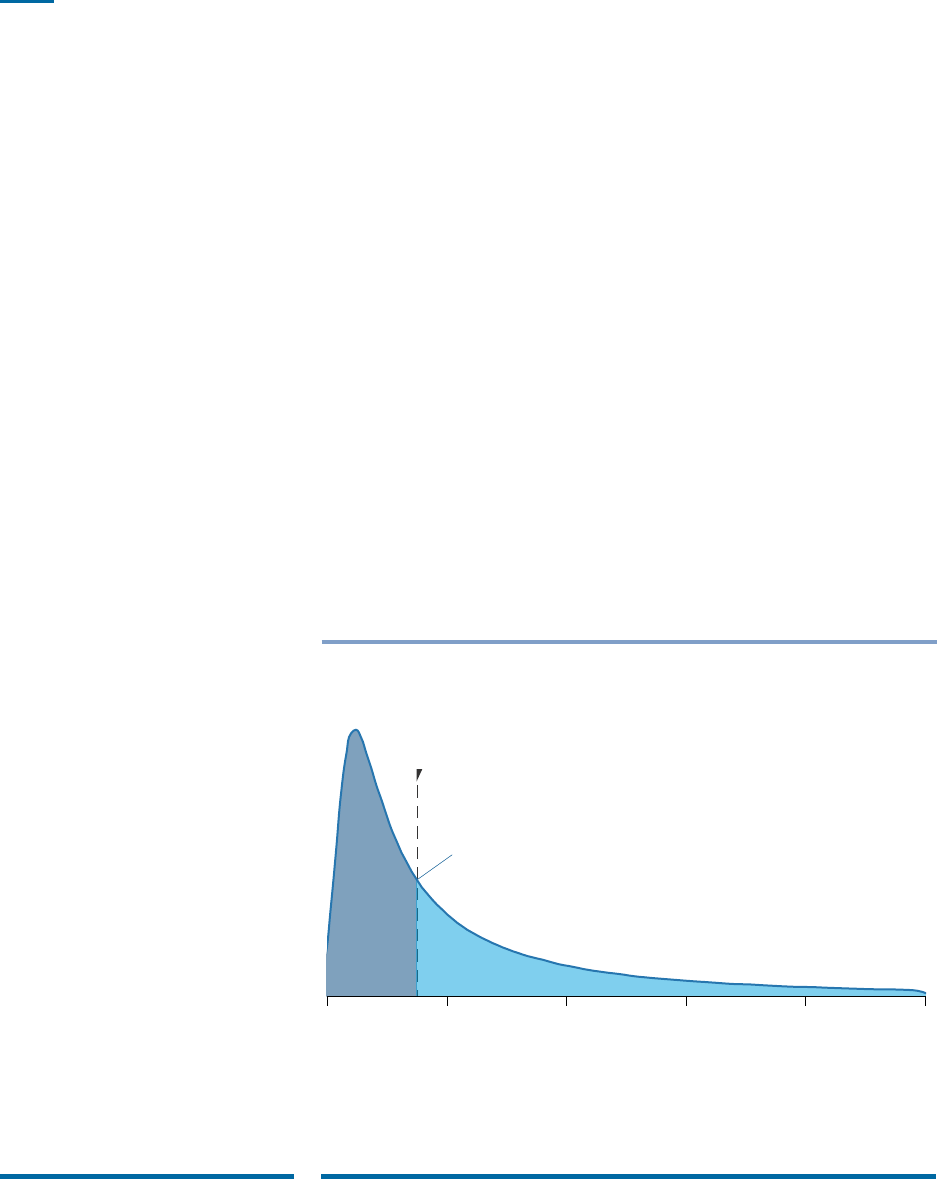

Figure 10 provides a textual descrip-

tion of each of these clusters—four

of which reflect relatively greater

regularity, and three of which are

much less regular. Farrell et al. (2018)

covers the specifics of our irregularity

measures and clusters in more detail.

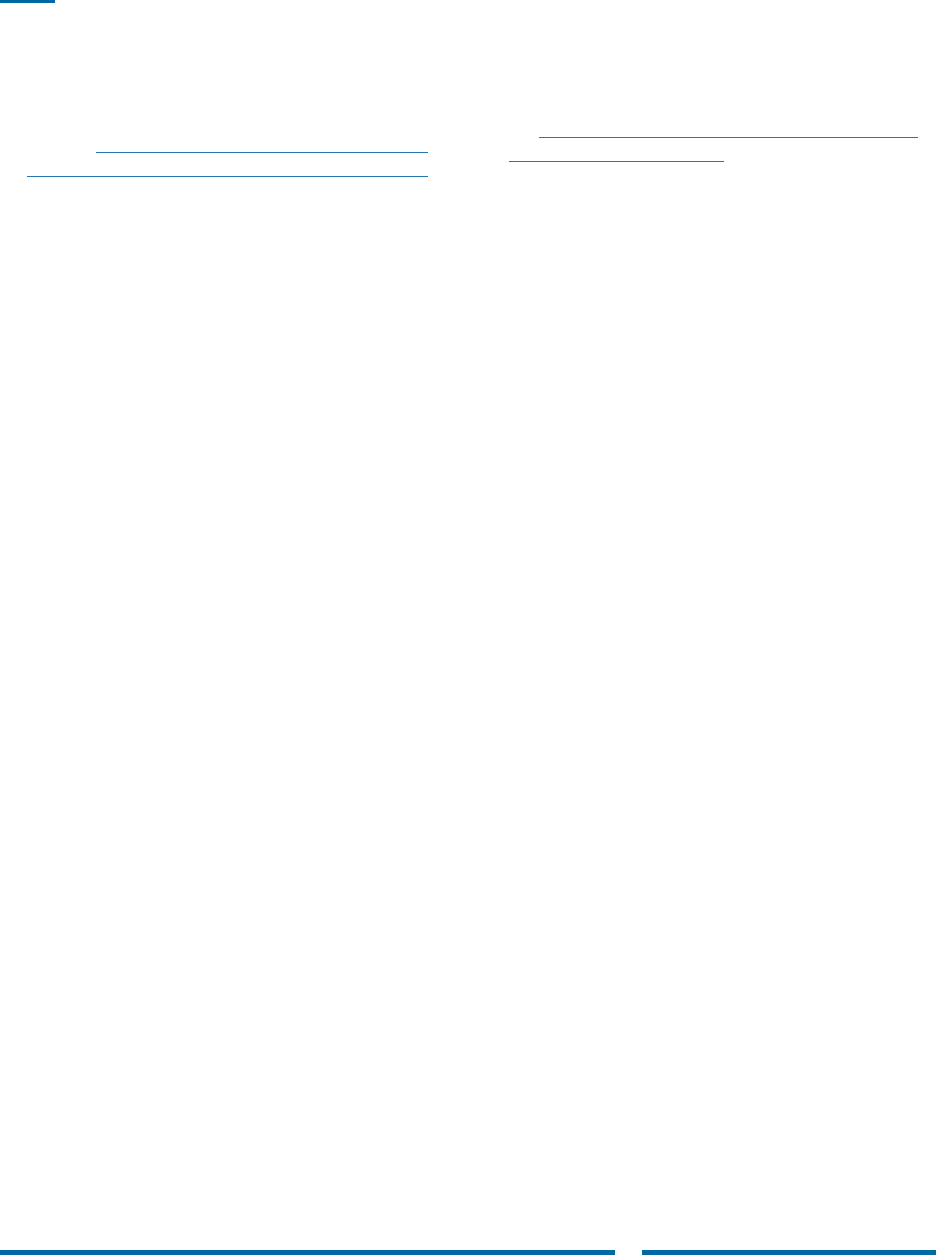

Figure 10: Firm cash-flow patterns can be classified into seven clusters, representing dierent cash-flow management

problems firms face

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

More regular operating cash flows

Less regular operating cash flows

Regular weekly

Regular weekly + financing

Semimonthly revenues

Erratic timing

Volatile expenses

Sporadic revenues

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Larger revenues and expenses

occur with weekly frequency,

with little deviation in amount

or timing.

Although the cash-flow

amounts do not show

particular volatility, their

timing is very inconsistent.

Very similar to cluster 1, only

with high utilization of financing.

Expenses are more volatile

than revenues, while the

reverse is true for most

other firms.

Larger revenues occur about

twice a month, while expenses

are paid about weekly.

Revenues are particularly

infrequent, about once

every 7 weeks, and the

amount is varies greatly.

Financing is heavily utilized.

Very similar to cluster 3, only with

high utilization of financing.

Semimonthly revenues + financing

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

14

Audretsch, David B. 2012. “Determinants of High-growth

Entrepreneurship.” OECD/DBA report. https://www.oecd.org/

cfe/leed/Audretsch_determinants%20of%20high-growth%20

firms.pdf

Birch, David L. and James Medo. 1994. “Gazelles.” In Labor

Markets, Employment Policy and Job Creation, edited by

Lewis C. Solomon and Alec R. Levenson, 159-168. Boulder:

Westview Press.

Farrell, Diana and Christopher Wheat. 2016. “Cash is King:

Flows, Balances, and Buer Days.” JPMorgan Chase Institute.

https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/report-

cash-flows-balances-and-buer-days.htm

Farrell, Diana and Christopher Wheat. 2017a.

“Mapping Segments in the Small Business Sector.”

JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://institute.jpmor-

ganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/

insight-mapping-smb-segments

Farrell, Diana and Christopher Wheat. 2017b. “The Ups and

Downs of Small Business Employment: Big Data on Payroll

Growth and Volatility.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://

www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/report-small-

business-payroll.htm

Farrell, Diana and Christopher Wheat. 2018. “Bend, Don’t Break:

Small Business Financial Resilience After Hurricanes Harvey

and Irma.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorgan-

chase.com/corporate/institute/report-bend-dont-break.htm

Farrell, Diana and Christopher Wheat. 2019. “The Small

Business Sector in Urban America: Growth and Vitality

in 25 Cities.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://institute.

jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/

report-small-business-outcomes-cities

Farrell, Diana, Christopher Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2017. “Paying

a Premium: Dynamics of the Small Business Owner Health

Insurance Market.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://insti-

tute.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/

report-small-business-health-insurance

Farrell, Diana, Christopher Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2018. “Growth,

Vitality, and Cash Flows: High-Frequency Evidence from 1

Million Small Businesses.” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://

www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/report-growth-

vitality-cash-flows.htm

Farrell, Diana, Christopher Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2019a.

“Gender, Age, and Small Business Financial Outcomes.”

JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/

corporate/institute/report-small-business-financial-out-

comes.htm

Farrell, Diana, Christopher Wheat, and Carlos Grandet. 2019b.

“Place Matters: Small Business Financial Health in Urban

Communities” JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmor-

ganchase.com/corporate/institute/report-place-matters.htm

Guzman, Jorge and Scott Stern. 2016. “The State of American

Entrepreneurship: New Estimates of the Quantity and Quality

of Entrepreneurship for 15 US States, 1988-2014.” NBER

Working Paper No. 22095. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22095

JPMorgan Chase and Initiative for a Competitive Inner City.

2016. “The Big Impact of Small Businesses on Urban Job

Creation: Evidence from Five Cities”. http://icic.org/wp-con-

tent/uploads/2016/10/JPMC_R1_BigImpact_FINAL_forpost.pdf

Pugsley, Bejamin W., Petr Sedlacek, and Vincent Sterk.

2018. “The Nature of Firm Growth.” CEPR Discussion

Paper No. DP12670. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.

cfm?abstract_id=3118318

Rossiter, Louis. 2009. “Rising Costs for Healthcare: Implications

for Public Policy”. https://www.nfib.com/Portals/0/PDF/

AllUsers/RisingHealth.pdf

References

A Cash Flow Perspective on the Small Business Sector

15

1 According to the Census Bureau Business Dynamics Statistics

data, firms with fewer than 500 employees created 1.4 million

net jobs in 2016, out of a total of 2.9 million net jobs created

that year. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/bds/

data/data-tables/2016-firm-and-estab-release-tables.html

2 The research findings shared in this synthesis were previ-

ously published by JPMorgan Chase Institute.

3 In our sample, a firm exits the market when it closes its

small business bank account.

4 See https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/

small-business-ownership.htm for details on employer small

business ownership by race, gender, and veteran status.

Endnotes

This material is a product of JPMorgan Chase Institute and is provided to you solely

for general information purposes. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views or

opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may dier from

the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research

Department or other departments or divisions of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its ali-

ates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information

has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or

its aliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its com-

pleteness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date

of this material and are subject to change without notice. The data relied on for this

report are based on past transactions and may not be indicative of future results.

The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any

particular client and is not intended as recommendations of particular securities,

financial instruments, or strategies for a particular client. This material does not con-

stitute a solicitation or oer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

©2020 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights

reserved. This publication or any portion

hereof may not be reprinted, sold, or

redistributed without the written consent of

J.P. Morgan. www.jpmorganchaseinstitute.com