NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

FINANCING MUNICIPAL WATER AND SANITATION SERVICES IN NAIROBI’S

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

Aidan Coville

Sebastian Galiani

Paul Gertler

Susumu Yoshida

Working Paper 27569

http://www.nber.org/papers/w27569

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

July 2020, Revised July 2021

The authors are grateful to the World Bank’s Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund (SIEF),

Development Impact Evaluation Department (DIME), J-PAL/MIT Urban Services Initiative and

the International Growth Center for financial support. The authors have benefited from comments

by Edward Glaeser, Marco Gonzales, Kelsey Jack, Bryce Millett Steinberg, Guadalupe Bedoya,

Gustavo Saltiel, Catherine Signe Tovey, Josses Mugabi, George Joseph, Ruth Kennedy-Walker,

Jeffrey Mosenkis, Laura Burke, Douglas MacKay, Chris Prottas, Mitsunori Motohashi, Martin

Gambrill, Arianna Legovini, Keziah Muthembwa, Camille Nuamah and participants in the 2019

Cities and Development conference, the 2020 NBER Summer Institute Urban Economics

Conference, and from a seminar at NYU in Abu Dubai. The study would not have been possible

without the continued efforts and long-term collaboration with the Nairobi City Water and

Sewerage Company staff including Nahashon Muguna, Jackson Munuve,

Kagiri Gicheha, Jason

Mwangi, Beldina Owade, Christine Machio, Paul Mwarania, Ephantus Mugo, Martin Nangole,

Lucy Njambi, Daisy Nyaboke and Owen Wanjala. Likewise, we thank Christine Ochieng, Paul

Mbanga, Wendy Ayres, Rajesh Advani, Jessica Lopez and Clifford Mwaura from the World

Bank who helped ensure a strong link between the research and operational activities. The Kenya

Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) team provided professional field support throughout the

program, with particular thanks to Frank Odhiambo, Bonnyface Mwangi, Geoffrey Onyambu,

John Paul Buleti, Allison Stone and Alice Kirungu. The authors also benefited from excellent

research assistance from Amy Dolinger, Marco Valenza and Duncan Webb. DIME Analytics

provided technical support throughout the analysis with Luiza Andrade conducting code

reproducibility checks. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are

entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank

and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the

governments they represent, nor the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The authors have no financial or material interests in the results in the paper.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2020 by Aidan Coville, Sebastian Galiani, Paul Gertler, and Susumu Yoshida. All rights

reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit

permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source.

Financing Municipal Water and Sanitation Services in Nairobi’s Informal Settlements

Aidan Coville, Sebastian Galiani, Paul Gertler, and Susumu Yoshida

NBER Working Paper No. 27569

July 2020, Revised July 2021

JEL No. C93,D04,O18

ABSTRACT

We estimate the impacts of two interventions implemented as field experiments in informal

settlements by Nairobi’s water and sanitation utility to improve revenue collection efficiency and

last mile connection loan repayment: (i) face-to-face engagement between utility staff and

customers to encourage payment and (ii) contract enforcement for service disconnection due to

nonpayment in the form of transparent and credible disconnection notices. While we find no

effect of the engagement, we find large effects of enforcement on payment. We also find no

effect on access to water, perceptions of utility fairness or quality of service delivery, on the

relationships between tenants and property owners, or on tenant mental well-being nine months

after the intervention. To counterbalance the increase in payments, property owners increased

rental income by renting out additional space. Taken together these results suggest that

transparent contract enforcement was effective at improving revenue collection efficiency

without incurring large social or political costs.

Aidan Coville

Development Impact Evaluation, DIME

The World Bank

1818 H Street N.W.

Washington, DC 20433

Sebastian Galiani

Department of Economics

University of Maryland

3105 Tydings Hall

College Park, MD 20742

and NBER

Paul Gertler

Haas School of Business

University of California, Berkeley

Berkeley, CA 94720

and NBER

Susumu Yoshida

The World Bank

1818 H Street N.W.

Washington, DC 20433

A randomized controlled trials registry entry is available at AEARCTR-0003556

1 Introduction

Some 844 million people lack clean drinking water and 2.4 billion people do not have im-

proved sanitation, most of which are living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

1

An estimated US$ 1.7 trillion is needed to finance the goal of universal access by 2030 (Hut-

ton and Varughese, 2016). With two-thirds of the world’s population expected to live in

cities by 2050, finding scalable and sustainable solutions to expand reliable urban water and

sanitation services is critical. However, basic service provision is not keeping up with rapid

urbanization. Africa’s cities, for instance, grew by 80% between 2000 and 2015, while access

to piped water declined from 40% to 33% (World Bank, 2017).

The primary route for expanding services in urban areas is through public utilities, but

utilities are struggling to deliver reliable services to connected households let alone increase

coverage (Trimble et al., 2016; World Bank, 2017; Soppe et al., 2018). Revenue collection

has become a major stumbling block for utility performance (Ahluwalia, 2002; World Bank,

2017). Losses from nonpayment of service use bills are significant. Utilities worldwide failed

to collect an estimated US$ 39 billion of billable water and US$ 96 billion in electricity

charges each year (Liemberger and Wyatt, 2019; Northeast Group, 2017). Nonpayment for

services lowers effective prices, and when effective prices fall below marginal cost, each new

customer becomes a financial liability and may lead to rationing (Burgess et al., 2020; McRae,

2015).

2

Water rationing is not only inconvenient but can have negative impacts on health

(Galiani et al., 2005; Ashraf et al., 2021). There is well-documented concern over service

quality degradation worldwide from poorly maintained infrastructure, and the vicious cycle

between low payment and deteriorating quality of services (Jiménez and Pérez-Foguet, 2011;

Cronk and Bartram, 2017; Foster et al., 2020; Dzansi et al., 2018; World Bank, 2017).

More financial stress comes from the problem of paying for the significant last mile

connection costs that constrain household access to the utility’s services (WaterAid, 2007;

Golumbeanu and Barnes, 2013; Lee et al., 2020). Significant investments in urban trunk in-

frastructure are underutilized when households close to water and sewer lines do not connect

(Kennedy-Walker et al., 2020). While subsidies have been effective at increasing household

connections (Lee et al., 2020; Guiteras et al., 2015), they are costly, potentially regressive,

and are limited by public budget constraints (Abramovsky et al., 2020).

Providing credit to households to amortize upfront connection costs offers an attractive

1

World Bank (water): https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/watersupply; World Bank (sanitation):

https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/sanitation

2

Many utilities have tariffs that even when fully paid do not cover operating costs, and, in settings where

only a minority have access to piped services, introduce a regressive subsidy in favor of connected households

(Abramovsky et al., 2020).

1

alternative to subsidies. For example, the provision of credit increased piped water connec-

tion rates in Morocco by 69% (Devoto et al., 2012). To overcome thin credit markets, utilities

are taking out commercial loans that they use to finance loans from the utility to customers.

Customers then repay these loans through additional installment payments to their monthly

bills. There is, however, an inherent financial risk to utilities if customers do not repay their

loans. Nonperforming loans must be paid for through either service degradation or out of

general tax revenues.

In Nairobi, until recently, household-level piped water and sanitation were not available

to residents living in informal settlements. Settlement residents, who make up an estimated

60% of Nairobi’s population, typically live in multi-household compounds with a shared pit

latrine and purchased water from utility public water kiosks and private vendors. In 2014,

Nairobi’s utility began expanding compound-level piped water and sanitation services to in-

formal settlements. Compounds were offered a combination of subsidies and loans to finance

the US$ 1,100 cost of connection to the new trunk lines. This consisted of a US$ 750 (69%)

subsidy and a loan for the rest. The utility obtained a commercial loan that they used to

finance the loans to property owners. Property owners then agreed to repay the loan to the

utility over time by adding installment payments to their monthly water and sewerage bills.

Between 2014 and 2018, the utility expanded services to 137,000 previously unconnected

people in informal settlements (World Bank, 2019).

However, after the expansion, the utility experienced significantly lower revenue collec-

tion than originally anticipated. In 2016, 40% of the newly connected property owners had

yet to make a single service or loan payment and the average share of bills and loans paid fell

from above 65% in 2014 to below 50% in 2018 (Figure 1). Service quality also deteriorated

over this period from 95% of compounds with piped water reporting having received service

in the past week in 2014 to 40% in 2018. In response, the utility considered two strategies to

improve revenue collection: (i) an engagement approach to encourage payment; and (ii) ser-

vice contract enforcement that allowed for disconnection for nonpayment.

3

Both approaches

are commonly used by utilities around the world to improve revenue collection efficiency, but

limited evidence exists on their costs and benefits (Hernandez and Laird, 2019; Szabó and

Ujhelyi, 2015). In this paper we report on the results of a field experiment designed to test

both strategies.

The first approach was a face-to-face meeting between tenants and the utility’s existing

outreach team to explain the financial status of the water and sewer bill, the consequences for

3

The utility requested support from the research team based on a long-standing relationship that began

in 2012 related to the last mile connection issues. See appendix for a description of the other interventions

designed to enhance revenue collection considered at the time.

2

the utility, and discuss what they could do to encourage property owners to make payment.

The idea was to empower renters to discuss such matters with property owners because

service disconnection would be a violation of their rental agreements as 93% of tenants had

piped water included in their rent. While the utility had primarily targeted property owners

in their previous outreach efforts, this new approach was designed to strengthen bottom-up

accountability.

The second approach was to systematically enforce the terms of the contract that the

property owners had signed with the utility, specifying service disconnection for property

owners with significant payment arrears.

4

Prior to the study, 82% of property owners were

eligible for disconnection under the contract’s terms, which made implementation of the de

jure policy infeasible. As a result, the de facto application of the disconnection policy was

ad hoc, which could potentially limit contract enforcement effectiveness and create opportu-

nities for extortion (Ashraf et al., 2016). Given the significant subsidy and loans given to

property owners for last mile connections and the importance of the sustainability of service

quality, the utility was in the process of systematizing contract enforcement to improve rev-

enue collection.

Contract enforcement is key to sustaining the rule of law and the process of economic de-

velopment (Glaeser and Shleifer, 2002). However, contract enforcement was potentially risky

for both the utility and for its customers. From the utility’s perspective, enforcement would

be effective if it improved payment and social costs were low. Currently connected residents

would benefit if the utility used the new revenues to improve service quality. Currently

unconnected residents would benefit if enhanced revenue collection were used to expand con-

nections. However, households that are disconnected could face added burdens in the form

of increased cost and reduced access to water sources. The utility might also face increased

customer dissatisfaction with perceived fairness and service quality leading to loss of political

support for the utility and government.

These potential risks motivated the utility to pilot enforcement to better understand the

costs and benefits. In practice, this meant exempting from disconnection a set of compounds

who otherwise would have been considered for disconnection to serve as a control group, while

ensuring compounds in the treatment group followed a clearly articulated contract enforce-

ment implementation plan. The criteria for disconnection were set at a substantially higher

level of nonpayment than specified in the contracts for more selective targeting. Enforcement

was then implemented along a strict selection protocol governed by (1) systematic identi-

fication of all disconnection-eligible compounds, (2) randomly selecting a subset to receive

4

Service disconnection for nonpayment was explicitly specified in the contract signed by property owners

when they agreed to receive the infrastructure upgrades to their property.

3

disconnection notices with clear instructions on how to pay or appeal for a financial hardship

exemption, (3) allowing a reasonable period of time for property owners to pay or appeal,

and (4) disconnecting services if they did not pay at least some of their outstanding bill in

a timely fashion or apply for a financial hardship exemption.

The intervention was implemented in a context where water and sanitation charges were

affordable, i.e., significantly below the 3% (water) and 5% (water and sanitation) thresholds

of monthly income for service affordability set by the United Nations (United Nations, 2010).

In addition, alternative water sources were available through utility-run public kiosks and

private vendors, which were the primary sources of water prior to the 2014 expansion of util-

ity piped water. During the intervention rollout, the utility maintained a transparent and

convenient process through which property owners could delay payment and disconnection

in the case of financial distress.

5

Using administrative data from the utility’s electronic billing and payment system, we

find that contract enforcement significantly increased both the likelihood of property owners

making a payment, and the overall amount paid. However, most of the change in payment

behavior took place shortly after enforcement took place, with no evidence of further in-

creases over time. This could be because the enforcement intervention was implemented as a

one-time policy and not as a permanent change. We also find no evidence of spillover effects

in the form of improved payment behavior among control property owners with compounds

in treatment clusters. The face-to-face engagement intervention had a precisely estimated

null effect.

In addition to the observed payment behavior, we did not find evidence that tenants were

negatively affected nine months after implementation of the enforcement intervention. Using

survey data, we find that water and sanitation service connections were not meaningfully

different between treatment and control compounds. This is because most property owners

whose service was disconnected were reconnected after agreeing to a payment plan. During

service interruptions tenants had access to water from kiosks operated by the utility and

private vendors and reported no reductions in water use nor increase in spending on water.

Moreover, we do not find evidence that the disconnection policy negatively affected either

tenants’ or property owners’ perceptions of fairness and quality of water service delivery, nor

did the policy affect the relationships of tenants and property owners. Finally, tenants were

no more likely to move out.

To counterbalance the effective increase in utility fees paid, property owners increased

their rental income predominantly by renting out additional space. Together, these results

suggest that the transparent contract enforcement of the disconnection policy increased pay-

5

More details related to the study’s ethical considerations can be found in the appendix.

4

ment and improved the financial position of the utility without incurring any observed social

costs on the tenants and property owners or political costs to the utility.

2 Contributions to the Literature

A significant body of research explores approaches to expanding access to services. With

a few exceptions (Devoto et al., 2012; Galiani et al., 2005), this work predominantly focuses

on rural settings (Lee et al., 2020; Whittington et al., 2020).

6

Problems with both expand-

ing access and service quality can be linked back to financial constraints. Our work adds to

the literature testing strategies to improve payment behavior and thereby relaxing financial

constraints on service delivery.

Despite the frequent use of service disconnections for nonpayment by utilities worldwide,

7

to our knowledge, there are no experimental studies that estimate their potential impact.

Jack and Smith (2020) explore the role of pre-paid electricity meters on service payments

and consumption patterns in South Africa. Pre-paid meters offer a technical solution to

payment problems by ensuring that customers only receive service if they provide upfront

payment rather than more standard post-paid systems and can be programmed to include

loan repayments. In effect, users are disconnected if they do not prepay. The study found

that switching to pre-paid meters reduced electricity usage by 14 percent, but still increased

overall municipal revenue through improved revenue collection. Pre-paid meters for water

were piloted in a few middle-income neighborhoods in Nairobi but were abandoned because

of vandalism and high fixed costs of installation (Heymans et al., 2014).

There is some limited evidence that outreach campaigns improve service payment. Szabó

and Ujhelyi (2015) find that simply delivering a payment “education campaign” increased

payment rates by 25% in an informal settlement in South Africa, although the effects were

short-lived. Rockenbach et al. (2019) find that information campaigns designed using psy-

chological commitment techniques increase payment by between 30-61%, but again only had

short run effects. More broadly, interventions that try to improve bottom-up accountability

– typically from communities to place pressure on service providers - have mixed results that

may be influenced by the heterogeneity of these groups and the existing top-down account-

ability measures in place (Björkman and Svensson, 2010; Olken, 2007; Serra, 2012).

6

Increasing sanitation coverage in rural area has been challenging when relying purely on behavioral

change approaches (Briceño et al., 2017; Cameron et al., 2019), and there has been more traction when this

is combined with financial subsidies, although this increases program costs (Clasen et al., 2014; Guiteras

et al., 2015).

7

For example, an estimated 15% of households in the United States received service disconnection notices

and 3% were disconnected in 2015 (Hernandez and Laird, 2019).

5

Observational studies provide insights into determinants of service payment behavior

such as households strategically delaying payment as a form of credit (Violette, 2020) or

the perceived ease of payment and social pressure being associated with prompt payment

(Mugabi et al., 2010). While experimental work on improving utility revenue collection has

started to grow, these papers mostly rely on administrative billing and basic demographic

data to assess impacts and typically limit their attention to two dimensions – payment and

consumption behavior (Allcott, 2011; Jack and Smith, 2020; Szabó and Ujhelyi, 2015; Rock-

enbach et al., 2019). Our study combines five years of daily administrative billing data with

rich primary survey data from property owners and tenants over the course of three years

on a range of outcomes that helps present a more comprehensive assessment of the potential

welfare implications of utility interventions.

Our study also contributes to the high-stakes contract enforcement approaches to improv-

ing regulatory compliance. The evidence on high-stakes contract enforcement is particularly

limited, especially when compared to lighter-touch information/engagement interventions.

The existing evidence on enforcement is mostly limited to developed country settings, most

prominently in the tax evasion literature (Slemrod et al., 2001; Kleven et al., 2011), and

to a lesser extent in environmental protection (Telle, 2013; Duflo et al., 2018). The small

number of studies exploring high-stakes enforcement in developing countries find significant

impacts. In Brazil, de Andrade et al. (2016) randomize inspections and fine firms if they

are found to be operating without a business license and find that the intervention increases

business registrations. In Costa Rica, Brockmeyer et al. (2019) find significant increases in

tax payments from credible enforcement emails. In Kenya, Bedoya et al. (2021) randomize

a regime of high-intensive inspections of health facilities with enforcement of warnings and

sanctions, including the risk of closure if they do not have a license to operate. These inspec-

tions successfully increase compliance with minimum patient safety standards for all types

of facilities without increasing patients’ payments or reducing facility use.

3 Institutional Context

Like many LMICs, Kenya’s constitution established the right to “reasonable standards

of sanitation” and “clean and safe water in adequate quantities”, and Kenya’s Vision 2030

set a goal of universal water and sanitation coverage. Achieving this vision faces important

challenges. Nairobi’s urban population has tripled over the past 25 years,

8

but access to safely

managed water fell from 62% in 2000 to 50% in 2017.

9

Water supply for existing customers

8

UN population dynamics data 2021

9

Joint Monitoring Program data: https://washdata.org/data/household!/

6

was only able to meet about 70% of demand and even that is with intermittent supply

(NCWSC, 2017).

10

Like in many developing countries, sanitation coverage is significantly

lower than water access, with approximately 18% of Kenya’s urban residents having a sewer-

connected facility (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2015).

3.1 Expansion into Informal Settlements

Nairobi’s water services board, Athi Water Works Development Agency, expanded wa-

ter and sanitation trunk lines into many of Nairobi’s informal settlements between 2012 and

2016. After the trunk infrastructure was in place, Nairobi’s water and sanitation utility could

offer compound-level connections to the piped system. Property owners were able to connect

their compounds to the trunk lines by signing a contract agreeing to be responsible for pay-

ing water and sanitation consumption and loan charges, and to service disconnection in the

event of nonpayment. The utility offered each property owner a comprehensive infrastruc-

ture upgrading package including (i) upgrading of existing latrines to be connection-ready

including filling pit latrines and building superstructures where needed; (ii) a single piped

water connection to the compound; (iii) a wash basin; (iv) a 400-liter water storage tank for

when supply was temporarily unavailable; and (v) the physical connection of the latrine(s)

to the newly built sewerage line.

11

The unsubsidized cost of this full package was approximately US$ 1,100 – twice the av-

erage monthly income of property owners in the target areas. The World Bank provided

grant financing to reduce the connection costs by 69%, and the utility took commercial

loans to finance loans from the utility to property owners for the rest. Property owners

paid off the loans in monthly installments of US$ 6 (US$ 4.50 for sewer and US$ 1.50 for

water) added to the monthly service use bills.

12

This was offered to property owners on a

voluntary opt-in basis, if they agreed to the terms of the contract and paid a US$ 16 upfront

deposit. Since these monthly loan installments were highly affordable – representing 1.1%

of property owner income on average – over 90% of property owners agreed to participate.

13

This resulted in an estimated 137,000 people living in Nairobi’s informal settlements gaining

10

While significant investments to expand water supply to the city are underway, rationing is expected to

continue. This limited supply is exacerbated by cartels that damage utility infrastructure and control water

supply in some parts of the city. Cartels were not active in the specific study areas during the time of the

research (World Bank, 2019).

11

The water connection program started prior to the sanitation expansion. Compounds started receiving

water connections from 2014, but only started receiving sanitation connections from 2016. Investment in the

water connection was a prerequisite for sanitation upgrading.

12

We use an exchange rate of 1 USD = 100 KES throughout.

13

These loan installment payments were lower than the drudging cost of pit latrines, about US$ 8.00 per

month, that many residents used prior to trunk line services.

7

access to compound-level piped water and sewer services between 2014 and 2018 (World

Bank, 2019).

The model to finance the last mile connection costs relied on the assumption that prop-

erty owners would repay their loans and pay the monthly service fees. During the course of

the program, however, it became clear that that the utility faced critical nonpayment issues.

In 2016, 40% of connected property owners had yet to make a single service payment or

loan installment even though the average property owner had already been connected for

1.3 years. Moreover, the average share of bills and loans paid fell from above 65% in 2014

to below 50% in 2018 (Figure 1).

14

Service quality deteriorated substantially over this time

period, including a city-wide rationing program that started in early 2017. Based on data

collected from a panel survey of 587 households from one of the settlements, the proportion

of compounds that received water from their water point in the week prior to the survey fell

from 95% to 40% between 2014 and 2018.

15

3.2 Compounds and Residents

Characteristics of property owners and tenants living in one such informal settlement,

Kayole Soweto, are presented in Table 1 for owners and Table 2 for tenants.

16

In Kayole

Soweto, almost all property owners are sole owners of their compounds with self-reported

sales’ values of about US$ 20,000 on average. Property owners are 51 years old, are 60%

male, 54% have completed secondary education or higher, and make US$ 551 in income per

month on average from all sources.

Property owners rent out space in 86% of the compounds and make the compound their

principal residence in about half. On average, the rental compounds have 7.7 distinct rental

rooms, and generate US$ 115 per month in total rent per compound, or US$ 83 in income

after deducting expenses. Approximately three quarters of tenants have written or verbal

month-to-month rental agreements and paid a deposit in 47% of the cases. Eighty percent

of individual tenancy rents fall between US$ 15 and US$ 35 per month and averages US$ 25.

A tenant makes US$ 137 on average in income per month which translates into an average

total compound renter income of US$ 1,306.

The primary source of water in the informal settlement is piped water. The utility

connects a single piped water and sewer line that serves the entire compound which is

considered a single customer. The property owner is responsible for paying the water and

14

The program target was an 80% collection rate, which is consistent with the Kenyan regulator guidelines.

15

We use data from a listing exercise that we conducted in 2014 and combine this with an updated listing

exercise conducted by the utility in 2018 which is described in further detail in Section 7.

16

Based on a survey of property owners and a random sample of their tenants conducted in Kayole Soweto

in 2015/2016.

8

sanitation bill, and these services are explicitly included in the rent in 93% of the compound

rental agreements. Customers use Jisomee Mita, a web-based ICT platform that enabled

property owners to use a mobile phone to self-read meters, receive and pay water bills, and

check their current balance at any time. While 80% of compounds have a piped water

connection, 7% report that their connection is not working. Because many households are

unable to access piped water in their homes, the utility also operates water kiosks where

residents can purchase clean water at a regulated price of US$ 0.2 per kiloliter.

3.3 Utility Charges and Reasons for Nonpayment

Piped water is affordable relative to income in this setting. In 2016 the average monthly

water service bill for Kayole Soweto property owners was US$ 4.20, which accounts for 3.6% of

compound rent, 0.3% of total compound resident income, or 1.1% of property owner income.

An additional US$ 6 per month was charged by the utility to repay the water connection

loan (US$1.50 for 30 months) and the sanitation loan (US$ 4.50 for 60 months). Sanitation

services were charged at 70% of the water consumption bill. Even with the inclusion of the

loan repayment, the total monthly contribution is significantly lower than the 3% threshold

used by the United Nations to assess water affordability and 5% threshold including san-

itation (United Nations, 2010). However, even with reliable service and affordable tariffs,

nearly 40% of property owners had yet to make a single payment for services since being

connected 1.3 years ago on average and the average time since the last payment was made

was 6 months. As a result of this nonpayment, property owners owed US$ 24 on average for

past water use and behind on US$ 38 of their infrastructure loan repayments.

Why did property owners not pay their loans or consumption bills? Figure 2 presents

property owner self-reported reasons for (i) not making a payment in the last 2 months

and (ii) never making a payment based on self-reported data collected from a 2018 survey

of 5,091 property owners in six settlements. Service quality was the most cited reason for

nonpayment, reported by about half of respondents, lack of liquidity was the second most

cited reason, and third was not knowing how to make payments. The payment system and

billing infrastructure were not a perceived constraint.

Next, we look at correlates with payment behavior within a regression framework, using

the 2018 survey data merged with the utility administrative billing data. The sample con-

sists of compounds that (i) have a water connection and (ii) have tenants. The dependent

variables include whether the property owner ever made a payment; (ii) the proportion of

bills paid; (iii) the outstanding proportion of water connection loan; and (iv) whether the

loan has been fully paid.

9

Two takeaways are clear from the results presented in Table 3. First, the associations

are consistent with reasonable priors: Property owners receiving better service, living on the

property, and more knowledgeable about payment procedures have better payment practices

– for both loans and consumption charges. Second, self-reported reasons for nonpayment

appear consistent with actual behavior measured in the regression analysis but also over-

estimate the role of some factors. Service quality is presented as the single most important

self-reported reason for nonpayment. While the regression analysis identifies this as an im-

portant contributor, it explains a substantially smaller amount of variation in payments than

the self-reported reasons for nonpayment.

Another factor that may influence payment behavior is accountability and enforcement.

The official policy of the utility allows for disconnection of water services if a property owner

is more than 30 days in arrears and has not responded to a formal notice after 15 days.

Property owners are notified and given at least 15 days to pay before service is cutoff or to

appeal for a delay in payment based on financial difficulty. Property owners are informed of

and consent to this remedy in their service contracts that they sign at the time of connection.

In practice, implementation of the disconnection policy was partial and ad hoc in terms of

determining which of the eligible property owners would be disconnected. The disconnection

policy is challenging to implement in informal settlements because of the potential for social

and political costs associated with disconnections, the potential for some property owners

not to be able to pay due to financial constraints, and the sheer size of the problem: 82% of

property owners were eligible for disconnection based on the formal policy, as of July 2018.

4 Interventions

To ensure basic information constraints were not to blame for low payment rates, an

initial awareness campaign was rolled out by the utility to all property owners in the six tar-

geted Nairobi informal settlements in August and September 2018. The utility delivered the

following activities in sequence: (i) A phone call to the property owner to collect up-to-date

contact information, provide basic information on how to read meters and pay bills, and

share their latest account balance on record; (ii) an on-site meter reading to ensure accurate

billing records; and (iii) an SMS to property owners providing the account balance based on

the meter reading.

Two additional approaches to encourage payment were rolled out experimentally by the

utility. The first was an engagement intervention in which compounds in payment arrears

received a face-to-face visit from the utility informing tenants about the current balance,

how payments could be made, and the importance of ensuring the property owner makes

10

payment for the utility to be able to provide quality service and avoid disconnection. Utility

staff followed a specific script loaded onto a tablet during each visit to ensure uniformity

in intervention delivery (see appendix). This intervention took place during September and

October of 2018 after the initial awareness campaign described above.

The second approach applied contract enforcement of the disconnection policy for non-

paying property owners. Compounds in payment arrears were given official notification that

they had to make payment, or their services would be disconnected.

17

This intervention in-

cluded the following steps to ensure enforcement was targeted, transparent, fair and credible:

Targeting: Among disconnection-eligible property owners in treatment areas, a tighter

selection rule was applied than the official policy to target those in significant arrears. Dis-

connection eligibility was determined by the number of months a property owner had not

paid, and the outstanding balance. This differed slightly by settlement. All property owners

needed to have an outstanding consumption balance of more than US$ 25, or around six

months of consumption charges for the average compound. This typically meant that they

would also be behind in paying their service connection loan. In addition, property owners

in two settlements where the program had first started operating needed to have missed at

least the past three months of service payments, while property owners in the remaining set-

tlements needed to have missed at least one month of service payment. The average service

balance among those presented with a disconnection notice was US$ 76 or around 18 months

of the average consumption bill.

Transparency: Property owners were contacted by utility community-development agents,

or CDAs, a minimum of five times over a four-month period to alert them about their arrears

and eligibility for disconnection. Communication campaigns were designed by sociologists

employed by the utility that had been working in the study settlements for many years and

had long-term relationships with community leaders.

18

The communication started with the

awareness phone call from the utility in August/September 2018. This was followed in Oc-

tober/November 2018 by a notice posted to the compound door and next to the water point

warning property owners of disconnection if payment is not made by a specified deadline

and providing a contact number for coordinating a payment arrangement or disputing the

17

The study was designed specifically to measure the impacts of tenant engagement and disconnection

policy enforcement. Of course, these two options are not exhaustive and there may be other policy avenues

that could be more effective. In fact, the government considered a broader set of options before ultimately

settling on studying engagement and enforcement.

18

These sociologists had also been responsible for leading regular community meetings prior to, and during

the infrastructure construction activities, and worked with the CDAs to deliver general awareness campaigns

on how to effectively utilize the upgraded water and sanitation facilities. This meant that the utility had

a daily presence in the settlements through the CDAs, and this was the primary route of communication

between the utility and communities.

11

bill (see appendix for example). The notification ensured that tenants were also informed

about the procedure. Third, an SMS warning and fourth, a phone call warning was made to

the property owner prior to the notification deadline, alerting them to pay within 48 hours

or be disconnected. Finally, the utility visited the compound on the deadline and made a

last request for payment before proceeding with disconnection.

Fairness: All property owners agreed to the utility’s disconnection policy in writing at

the time of receiving their water and sanitation infrastructure upgrade. Poster notifications

included a contact number for property owners or tenants to contact the utility and dispute

their balance or provide justification for why they were unable to afford to pay for the service

and agree on a payment plan. If property owners were found to be indigent and/or agreed

to a flexible payment plan, they would not be disconnected. Tenants were made aware of

the outstanding balance and could also pay the bills themselves to avoid disconnection. If

none of these remedies were taken and service was disconnected, tenants could revert to the

status quo prior to receiving the piped services - purchasing water from various water kiosks

operated privately or by the utility in the settlement. Since piped water was intermittent,

these were the same water sources tenants were currently using in conjunction with their

piped services.

Credibility: The utility followed through with disconnections if there was no attempt by

the property owner or tenants to make any payment. However, although the official policy

requires property owners to pay a reconnection fee and the full outstanding balance, this

was not enforced in this setting, and property owners that showed a willingness to cooperate

with the utility could be reconnected. Since the reconnection process was quick and low-cost

this meant that people could be reconnected soon after disconnection with limited cost.

The implementation of disconnections in this setting are low-cost, reversible activities.

The disconnection costs the utility approximately US$ 3.30.

19

Reconnection costs are simi-

lar in magnitude to disconnection costs. The disconnection notices were delivered from 29

October to 7 November of 2018, with follow ups and disconnections taking place during

November and December of the same year.

19

Disconnection costs include communication costs of notifying the customer (printing the poster notifica-

tion, the phone call reminder and the SMS reminder) of about US$ 0.30 plus labor costs of the disconnection

of about US$ 3.00. The disconnection is conducted by a trained utility staff member who is paid approxi-

mately US$ 30 a day.

12

5 Experimental Design

All informal settlement property owners in the utility database were first called to confirm

contact details and receive the base intervention. Eligibility criteria into the study included:

(i) property owners were able to be contacted and their contact details could be updated;

(ii) their payment accounts were in arrears and (iii) property owners did not hold multiple

accounts (multiple-property owners). All eligible property owners then received the basic

information intervention and contact details were updated.

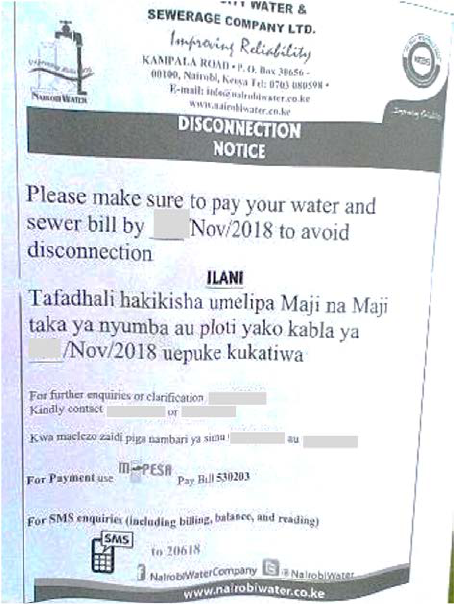

Figure 3 describes the experimental design and sample selection. Starting from the group

of 5,091 property owners that completed the phone survey in August 2018, just over 50%

(2,584) indicated that they had tenants residing in the property. These 2,584 accounts were

randomly assigned into a group of 1,292 who received the engagement treatment and an

equally sized control group. The engagement intervention was successfully implemented in

885 (69%) of the 1,292 accounts assigned to the treatment group. Reasons for non-compliance

included not being able to find the property, tenants being unavailable at the time of visit,

and incorrect recording of the compound as having tenants when this was not the case.

For the enforcement intervention, we started with the same 5,091 accounts used for the

engagement intervention and removed two informal settlements because these settlements

are characterized by multi-story apartment blocks where individual disconnections pose a

technical challenge. The remaining sample of 3,253 accounts from 4 settlements (which in-

cluded compounds with and without tenants) were then clustered by street using GPS and

address data. This generated 147 distinct street clusters. We then randomized 73 clusters

consisting of 1,584 accounts into the treatment group, while the remaining 74 clusters (1,669

accounts) were left as pure controls. Within the treatment clusters there were 649 com-

pounds eligible for disconnection, and 327 of these were randomly assigned to receive the

disconnection notifications, following the protocols described in Section 4. The remaining

322 control compounds in the treatment clusters, as well as the 674 disconnection-eligible

compounds in pure control clusters were exempted from the policy for the period of the

study. Figure 4 illustrates how the two-stage randomization was applied in one settlement

to allow us to test for direct and spillover effects associated with the enforcement interven-

tion. The disconnection notices were ultimately delivered to 299 compounds (91.4%). In the

remaining cases (28), compounds were found to have already had their services disconnected

by the utility in which case no notice was delivered. The number of compounds actually

disconnected was 96 or 2.9% of the 3,253 compounds eligible for disconnection in the study.

20

20

In six additional cases, despite property owners not coming to an agreement with the utility, enforcement

was not possible because of of the technical complexity of the connection.

13

Of these, 74% had tenants.

The two interventions were implemented sequentially. The engagement intervention was

implemented in September and October 2018, while the enforcement intervention was im-

plemented in November and December of the same year.

6 Empirical Strategy

The engagement intervention was individually randomized among compounds with ten-

ants, and we estimate the intention to treat (ITT) effect by means of its sample analog:

IT T “ EpY

it

|T

i

“ 1q ´ EpY

it

|T

i

“ 0q (1)

where Y

it

is the outcome of interest for compound i at month t pt “ 1, 9q after the inter-

vention was completed; and T

i

is equal to 1 if compound i is assigned to receive treatment

and 0 otherwise. Note that treatment status does not change over time. We condition the

analysis on settlement fixed effects and estimate robust standard errors.

The enforcement intervention was delivered as a clustered randomization. In this case

we estimate the ITT by means of its sample analog:

IT T “ EpY

ijt

|T

ij

“ 1, C

j

“ 1q ´ EpY

ijt

|C

j

“ 0q (2)

where C

j

is the cluster j indicator which is equal to 1 if the cluster was assigned to treat-

ment and 0 otherwise. The sample in both treatment and control clusters includes only

disconnection-eligible compounds. Finally, to measure spillovers to the non-treated units

(SNT) for the enforcement intervention, we estimate the sample analog of:

SN T “ EpY

ijt

|T

ij

“ 0, C

j

“ 1q ´ EpY

ijt

|C

j

“ 0q (3)

In the estimation of the sample analogs of equations [2] and [3] we condition on settlement

fixed effects given that the randomization was stratified at that level. Standard errors are

clustered at the street level, which was the level at which the randomization was assigned.

7 Data and Outcomes

We use high-frequency administrative billing and payment data from the utility to mea-

sure our primary payment outcomes. Jisomee Mita is a web-based ICT platform that enabled

property owners to use a mobile phone to self-read meters, receive and pay water bills, and

14

check their current balance at any time. Jisomee Mita data contains water consumption,

invoice amounts, payment history, current balance, and contact information of the property

owner. When payments or balance checks are submitted, the Jisomee Mita data are updated

automatically. However, monthly standing charges are applied to each account independent

of whether a property owner made a payment or billing enquiry which means that each

property owner’s balance is updated at least once a month.

The billing data is complemented with tenant and property owner survey data. A short

baseline listing phone survey of property owners was conducted in August and September

2018. This captured ownership and water/sanitation connection status, property owner res-

idency and number of paying tenants in the compound.

From August to October 2019 a follow up survey of both property owners and tenants

included in the enforcement intervention captured data on rent, service-level satisfaction,

political engagement, property owner-tenant interactions, water use and practices, mental

well-being and general demographic measures of one randomly selected tenant and the cor-

responding property owner from each compound in the sample.

We use utility billing data to generate payment outcomes. This includes: (1) the propor-

tion of property owners making a payment for water/sewer charges since the intervention,

(2) the total amount paid by property owners’ post-intervention and (3) the proportion of

outstanding service charges paid post-intervention. The data spans the entire period from

when the first property owners were connected in 2014 up to nine months after the interven-

tions were implemented (September 2019).

We rely on the follow up tenant and property owner survey to measure a range of out-

comes that assess the possible welfare effects of the enforcement intervention. We collect

measures related to water and sanitation infrastructure and use to assess how the interven-

tion may have affected access: whether the compound had a pour-flush toilet and piped

water connection at the time of the endline, whether the water connection was working, the

main source of water used by compound residents, the amount of time spent fetching water

in the last week, the amount spent on water in the last month, and the overall piped water

consumption in the compound. We also capture a range of outcomes that may be affected by

the intervention and changes in water and sanitation access. Here we combine like outcomes

into weighted, standardized indices following Anderson (2008) to reduce the potential for

false positives from multiple hypothesis testing. We generate the following indices (full list

of sub-indicators is presented in the appendix Tables A1 and A2):

Tenant-Property owner relationship: For the property owner index this includes prop-

erty owner perceptions on whether tenants complain about the water and sewer facilities or

about the general conditions of the compound, and whether tenants keep the compound in

15

a good condition. For tenants, we simply ask how they would rate their relationship with

the property owner from 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent).

Perception of service quality: Tenant / Property owner agrees or strongly agrees that

they are satisfied with utility services, the utility services improve people’s lives and pro-

vides clear communication, the government is trying to improve their lives, and (reverse

coded) the government is not interested in helping the community.

Perception of service fairness: Tenant / Property owner agrees or strongly agrees that

the utility enforcement mechanisms are fair and bills are accurate and fair.

Activism: Whether the compound has a committee, tenants have reached out to commu-

nity leaders, participated in community meetings, or are members of community committees.

Psychological well-being: We include a set of standardized measures to capture different

dimensions of psychological well-being among tenants, including Cohen’s four-item stress

scale (Cohen et al., 1983), depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D)

seven-point scale (Radloff, 1977)), optimism (Rosenberg optimism questionnaire (Rosenberg,

1965)), and the World Value Survey (WVS) measures of happiness, trust and life satisfac-

tion. The psychological well-being index in turn is a standardized weighted average of these

sub-indices.

In addition to the indices, we measure rent and rental income, migration and general

socioeconomic measures of property owners and tenants to explore possible effects on rent

and associated gentrification. We report the results from the indices in the main paper and

include the results of all sub-indicators in the appendix Tables A1 and A2.

8 Results

8.1 Baseline Balance

We present descriptive statistics and baseline comparisons between treatment and control

groups for our primary outcome measures using the administrative payment data on 6 August

2018 and 28 October 2018 to coincide with the download dates for the data sets used for

the randomized assignment of the engagement and enforcement interventions respectively.

Appendix Table A3 presents comparisons for each group and we find balance on most key

measures covered.

21

Only 2 out of 45 comparisons are statistically significantly different from

zero at conventional levels.

21

Regressions used to estimate the treatment effects reported below are replicated including variables that

are not balanced as covariates and neither the sign nor significance of any of the estimates change.

16

8.2 Payment Behavior

We find a precisely estimated null effect of the engagement intervention for all primary

payment outcomes and time periods measured in Table 4. The control group payments

increase steadily over the nine-month period from 30.1% of property owners having made

payments one month after the intervention to 55.8% having made at least one payment by

nine months (cumulative). However, compounds being exposed to the engagement interven-

tion track almost the exact same trajectory as their control comparison. The total amount

paid, and proportion of balance paid off are similarly indistinguishable across treatment and

control group.

In contrast to the engagement intervention, we find a sharp increase in payment behav-

ior among compounds exposed to the disconnection notices (Table 5). The likelihood of

payment within one month almost quadruples - increasing by 30 percentage points from 11

percentage points (p-value < 0.001). This difference in payment likelihood sustains through

the nine-month period, although with a slight decline relative to the control group. A sim-

ilar pattern is found for the total payments after one month, which increases by US$ 8.80

(p-value < 0.001) from a base of US$ 5.02. After this sharp initial increase, the difference

remains roughly constant between treatment and control groups while both increase over

time. Treatment compounds have paid off 11.3 percentage points more of their balance than

control compounds after the first month of intervention (p-value < 0.001). Control com-

pounds begin to catch up gradually over the nine months, closing this gap to 7.8 percentage

points (p-value = 0.005).

Figure 5 presents the full time series data available from the daily payment information

extracted from the utility billing database. The visualization strengthens the main messages

identified through the regression results. First, we find strong evidence of balanced payment

practices across treatment and control groups from 2014 when property owners first started

connecting to October 2018 just before the enforcement intervention. Second, we see that

the payment trajectories continue to overlap after November 2018 when comparing the en-

gagement intervention group to the control. Third, we see a sharp jump in the enforcement

intervention group immediately after the intervention was delivered, which then stabilizes

over time, suggesting that most of the impact identified in the regressions is driven by the

behavior change in the first month after the intervention.

8.3 Spillovers

To test for spillovers on the payment behavior of disconnection-eligible property owners

we compare control compounds in treatment clusters to the equivalent disconnection-eligible

17

property owners in control clusters and find no significant difference between the groups,

suggesting no discernible spillover effects from the program using our originally specified

empirical strategy for estimating spillovers (Table 6, Panel A). In Table 6, Panel B we report

similar results for disconnection-ineligible property owners suggesting that the enforcement

intervention had no observable spillovers on paying property owners either.

8.4 Heterogenous Treatment Effects on Payment Behavior

We consider two sets of sub-group analysis. First, the calculus for resident property

owners is likely to be different to that for non-resident property owners (the former would be

more directly affected by service disruption in the enforcement intervention, and potentially

more accessible in the engagement intervention). Second the constraints and decisions to

make payment may be different when considering the intensive (getting payers to pay more)

versus the extensive margin (inducing those that have never made a payment to start paying).

The appendix Tables A4 and A5 present sub-group analyses for property owner residency

status and the intensive vs. extensive margin of payment respectively. In both cases we find

no clear evidence of strong differences across these subgroups.

8.5 Water Access and Use

To measure social and economic costs of the enforcement intervention we use survey

data collected nine months after the intervention, as reported in Section 7. Estimated

impacts are presented in Table 7. The enforcement intervention had little effect on compound

connections to water and sanitation services. The majority of the 96 disconnected compounds

were reconnected after agreeing to pay a portion of their balance. We observe 27 of these

compounds made a payment after being disconnected, with 20 of these payments being

made within one month of the disconnection. The remaining compounds were reconnected

without requiring a payment if they agreed on a plan with the utility. Compounds receiving

the enforcement intervention have statistically indistinguishable piped water and sanitation

connection rates at endline. This remains true when considering whether the piped water

connection is currently working. We also find little evidence of illegal connections based on

enumerator observation (3 cases across the sample).

Many households with piped water do not report this as their primary water source.

Only 30.6% of control households report using piped water as their main source of water,

which is 4.4 percentage points higher among treatment households, but non-significant (p-

value=0.243). Many households in both groups are more likely to rely on water kiosks or

boreholes (40%) than piped water. Both groups report spending similar amounts on water

18

for all uses in the last month (Control: US$ 6.62; Treatment: US$ 6.86; p-value = 0.803) and

total time spent collecting water in the past week (Control: 118 minutes; Treatment: 100

minutes; p-value = 0.388), although this measure is noisy. Unsurprisingly then, we find no

changes in overall piped water consumed based on meter readings at compounds during the

endline survey. Overall, nine months after the interventions, access to water and sanitation

were indistinguishable between treatment and control groups.

The study had originally intended to include child health as a secondary outcome and had

collected maternal-reported illness symptoms for children under five. However, we choose not

to include analysis of these outcomes for two reasons. First, sample sizes were very low since

not all surveyed households had children under five. Second, it is unlikely that there would

be any impact on health since there was no impact on the primary mechanism through which

the intervention could have impacted health, i.e., access to water and sanitation services.

8.6 Performance Perceptions and Political Costs

We find no effect of the intervention on perceptions of service delivery quality and fairness

among property owners or tenants (Table 7). Similarly, we find no impacts on the strength

of the relationship between property owners and tenants, as reported by either group. Com-

munity activism among tenants, too, does not differ across groups. All indices have effect

size point estimates with small absolute values, and the signs of these differences vary, sug-

gesting no obvious pattern. The full set of indicators from which these indices are calculated

is presented in the appendix, which similarly finds no discernible pattern (Appendix Tables

A1 and A2). The only significant difference found is an 11.3-percentage point improved

perception among property owners that “water bills are accurate”. Given the high number

of variables and potential for false positives, we interpret the results overall as showing no

meaningful impact of the intervention on any of the outcomes measured.

8.7 Psychological Well-Being

In total we measure seven constructs (depression, life satisfaction, stress, happiness, self-

esteem, trust, and life orientation), collected among tenants. We find no impact of the

intervention on the overall psychological well-being index which combines these sub-indices

(Table 7). The full set of seven constructs is presented in the appendix, which finds no

statistically significant differences across these either (Table A6).

19

8.8 Rental Market

We find that property owner rental income increases significantly from US$ 62.58 by US$

23.88 (p-value = 0.019; Table 8). Interestingly, this does not appear to be driven by increases

in tenant rental prices. Control households report paying US$ 33.06 a month in rent, which

is indistinguishable from treatment household rents. While property owners in treatment

areas are slightly more likely to have increased rent in the past six months, this is only 3.6

percentage points higher and borderline significant (p-value = 0.091) in the treatment group

which cannot explain the significant increases in rental income that they receive. However,

we find a large and significant increase in the proportion of property owners renting out at

least part of their compound, which increases from 58.9% by 13.5 percentage points (p-value

< 0.001). Since there is a small imbalance in this indicator at baseline, we rerun the analysis,

including this measure as a lagged dependent variable and find that the significant increase

holds, although with a reduced point estimate on both the proportion of property owners

renting out their compound, and rental income. The results suggest that property owners

responded to an increase in effective water and sanitation service charges from increased

contract enforcement by becoming more likely to rent out parts of their compound. This

increased rental income to cover the increased costs.

9 Conclusion

The status quo in delivery of basic services excludes millions of poor households. Achiev-

ing universal access to improved water and sanitation requires innovations in service delivery

approaches to help reduce the gap between available resources and the estimated costs of

achieving national and global targets. Low-income households in urban centers facing high

growth rates and stressed infrastructure are of particular concern. While providing credit

to overcome high upfront costs to water and sanitation infrastructure connections has been

shown to substantially increase take up in some settings, the sustainability of this model

of infrastructure expansion is predicated on the repayment of loans by customers. In six

of Nairobi’s informal settlements where compounds received comprehensive water and san-

itation infrastructure upgrades, we find repayment on these loans, and payment of general

service charges, is well below targets, despite these charges being affordable under standard

global benchmarks.

We test two common interventions used by utilities to improve revenue collection ef-

ficiency. The first – a face-to-face engagement intervention aimed at spurring bottom-up

accountability from tenants to property owners, had a precisely estimated null effect on pay-

20

ment behavior in our setting. The second intervention – contract enforcement in the form of

targeted, transparent, flexible and credible disconnection notices quadrupled the likelihood

of property owners making a payment in the month of the intervention. We see limited ev-

idence of further increases nine months after the intervention, and no evidence of potential

spillover effects of the enforcement intervention on other property owners. This is possibly

attributable to the fact that owners viewed the enforcement intervention as a onetime event

rather than a permanent change in policy.

We did not find evidence that residents were negatively affected by the contract en-

forcement intervention nine months after implementation. Water and sanitation service

connections and water consumption were not meaningfully different between treatment and

control compounds. This is because most property owners whose service was disconnected

were quickly reconnected after agreeing to a payment plan and during service interruptions

residents had access to water from kiosks operated by the utility and private vendors. More-

over, contract enforcement did not affect either tenants’ or property owners’ perceptions of

fairness and quality of water service delivery, nor affect the relationships of tenants and prop-

erty owners. Finally, tenants were no more likely to move out. Taken together these results

suggest that transparent contract enforcement was effective at improving revenue collection

efficiency without incurring large social or political costs.

21

References

Abramovsky, L., L. Andrés, G. Joseph, J. P. Rud, G. Sember, and M. Thibert (2020). Study

of the Distributional Performance of Piped Water Consumption Subsidies in 10 Developing

Countries. The World Bank.

Ahluwalia, M. S. (2002, September). Economic reforms in India since 1991: Has gradualism

worked? Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (3), 67–88.

Allcott, H. (2011). Social norms and energy conservation. Journal of public Economics 95 (9-

10), 1082–1095.

Anderson, M. L. (2008). Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early inter-

vention: A reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and early training projects.

Journal of the American statistical Association 103 (484), 1481–1495.

Ashraf, N., E. Glaeser, A. Holland, and B. M. Steinberg (2021). Water, health and wealth:

The impact of piped water outages on disease prevalence and financial transactions in

Zambia. Economica.

Ashraf, N., E. L. Glaeser, and G. A. Ponzetto (2016). Infrastructure, incentives, and insti-

tutions. American Economic Review 106 (5), 77–82.

Bedoya, G., J. Das, and A. Dolinger (2021). Randomized regulation: The impact of inspec-

tions on health markets.

Björkman, M. and J. Svensson (2010). When is community-based monitoring effective?

evidence from a randomized experiment in primary health in Uganda. Journal of the

European Economic Association 8 (2-3), 571–581.

Briceño, B., A. Coville, P. Gertler, and S. Martinez (2017). Are there synergies from com-

bining hygiene and sanitation promotion campaigns: evidence from a large-scale cluster-

randomized trial in rural Tanzania. PloS one 12 (11), e0186228.

Brockmeyer, A., S. Smith, M. Hernandez, and S. Kettle (2019). Casting a wider tax net:

Experimental evidence from Costa Rica. American Economic Journal: Economic Pol-

icy 11 (3), 55–87.

Burgess, R., M. Greenstone, N. Ryan, and A. Sudarshan (2020). The consequences of treating

electricity as a right. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (1), 145–69.

22

Cameron, L., S. Olivia, and M. Shah (2019). Scaling up sanitation: evidence from an RCT

in Indonesia. Journal of development economics 138, 1–16.

Clasen, T., S. Boisson, P. Routray, B. Torondel, M. Bell, O. Cumming, J. Ensink, M. Free-

man, M. Jenkins, M. Odagiri, et al. (2014). Effectiveness of a rural sanitation programme

on diarrhoea, soil-transmitted helminth infection, and child malnutrition in Odisha, India:

a cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health 2 (11), e645–e653.

Cohen, S., T. Kamarck, and R. Mermelstein (1983). A global measure of perceived stress.

Journal of health and social behavior , 385–396.

Cronk, R. and J. Bartram (2017). Factors influencing water system functionality in Nigeria

and Tanzania: A regression and bayesian network analysis. Environmental Science &

Technology 51 (19), 11336–11345. PMID: 28854334.

de Andrade, G. H., M. Bruhn, and D. McKenzie (2016, 10). A Helping Hand or the Long

Arm of the Law? Experimental Evidence on What Governments Can Do to Formalize

Firms. The World Bank Economic Review 30 (1), 24–54.

Devoto, F., E. Duflo, P. Dupas, W. Parienté, and V. Pons (2012). Happiness on tap: Piped

water adoption in urban Morocco. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4 (4),

68–99.

Duflo, E., M. Greenstone, R. Pande, and N. Ryan (2018). The value of regulatory discretion:

Estimates from environmental inspections in India. Econometrica 86 (6), 2123–2160.

Dzansi, J., S. Puller, B. Street, and B. Yebuah-Dwamena (2018). The vicious circle of

blackouts and revenue collection in developing economies: Evidence from Ghana.

Foster, T., S. Furey, B. Banks, and J. Willetts (2020). Functionality of handpump water sup-

plies: a review of data from sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. International

Journal of Water Resources Development 36 (5), 855–869.

Galiani, S., P. Gertler, and E. Schargrodsky (2005). Water for life: The impact of the

privatization of water services on child mortality. Journal of political economy 113 (1),

83–120.

Glaeser, E. L. and A. Shleifer (2002). Legal origins. The Quarterly Journal of Eco-

nomics 117 (4), 1193–1229.

Golumbeanu, R. and D. Barnes (2013). Connection charges and electricity access in sub-

Saharan Africa.

23

Guiteras, R., J. Levinsohn, and A. M. Mobarak (2015). Encouraging sanitation investment

in the developing world: a cluster-randomized trial. Science 348 (6237), 903–906.

Hernandez, D. and J. Laird (2019). Disconnected: Estimating the national prevalence of

utility disconnections and related coping strategies. Philadelphia, PA: American Public

Health Association.

Heymans, C., K. Eales, and R. Franceys (2014). The limits and possibilities of prepaid water

in urban Africa.

Hutton, G. and M. Varughese (2016). The Costs of Meeting the 2030 Sustainable Develop-

ment Goal Targets on Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene. The World Bank.

Jack, K. and G. Smith (2020, April). Charging ahead: Prepaid metering, electricity use, and

utility revenue. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12 (2), 134–68.

Jiménez, A. and A. Pérez-Foguet (2011). The relationship between technology and function-

ality of rural water points: evidence from Tanzania. Water science and technology 63 (5),

948–955.

Kennedy-Walker, R., N. Mehta, S. Thomas, and M. Gambrill (2020). Connecting the un-

connected.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health/Kenya, National AIDS Control

Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, and National Council for Population

and Development/Kenya. (2015). Kenya demographic and health survey 2014. Technical

report.

Kleven, H. J., M. B. Knudsen, C. T. Kreiner, S. Pedersen, and E. Saez (2011). Unwilling or

unable to cheat? evidence from a tax audit experiment in denmark. Econometrica 79 (3),

651–692.

Lee, K., E. Miguel, and C. Wolfram (2020). Experimental evidence on the economics of rural

electrification. Journal of Political Economy 128 (4), 1523–1565.

Liemberger, R. and A. Wyatt (2019). Quantifying the global non-revenue water problem.

Water Supply 19 (3), 831–837.

McRae, S. (2015). Infrastructure quality and the subsidy trap. American Economic Re-

view 105 (1), 35–66.

24

Mugabi, J., S. Kayaga, I. Smout, and C. Njiru (2010). Determinants of customer decisions

to pay utility water bills promptly. Water Policy 12 (2), 220–236.

NCWSC (2017). Equitable water distribution program.

Northeast Group (2017, May). Electricity theft and non-technical losses: Global markets,

solutions, and vendors. Technical Report ID: 4311626.

Olken, B. A. (2007). Monitoring corruption: evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia.

Journal of political Economy 115 (2), 200–249.

Patil, S. R., B. F. Arnold, A. L. Salvatore, B. Briceno, S. Ganguly, J. M. Colford Jr, and

P. J. Gertler (2014). The effect of India’s total sanitation campaign on defecation behaviors

and child health in rural madhya pradesh: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS

Med 11 (8), e1001709.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The ces-d scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the

general population. Applied psychological measurement 1 (3), 385–401.

Rockenbach, B., S. Tonke, and A. R. Weiss (2019). From diagnosis to treatment: A large-

scale field experiment to reduce non-payments for water.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton university press.

Serra, D. (2012). Combining top-down and bottom-up accountability: evidence from a

bribery experiment. The journal of law, economics, & organization 28 (3), 569–587.

Slemrod, J., M. Blumenthal, and C. Christian (2001). Taxpayer response to an increased

probability of audit: evidence from a controlled experiment in Minnesota. Journal of

public economics 79 (3), 455–483.

Soppe, G., N. Janson, and S. Piantini (2018). Water Utility Turnaround Framework. World

Bank.

Szabó, A. and G. Ujhelyi (2015). Reducing nonpayment for public utilities: Experimental

evidence from South Africa. Journal of Development Economics 117, 20–31.

Telle, K. (2013). Monitoring and enforcement of environmental regulations: Lessons from a

natural field experiment in Norway. Journal of Public Economics 99, 24–34.

Trimble, C., M. Kojima, I. P. Arroyo, and F. Mohammadzadeh (2016). Financial Viability

of Electricity Sectors in sub-Saharan Africa: Quasi-Fiscal Deficits and Hidden Costs. The

World Bank.

25

United Nations (2010). Eight short facts on the human right to water and sanitation.

Violette, W. (2020). Microcredit from delaying bill payments.

WaterAid (2007). Water, environmental sanitation and hygiene programme for urban poor.

Technical report.

Whittington, D., M. Radin, and M. Jeuland (2020, 01). Evidence-based policy analysis?

The strange case of the randomized controlled trials of community-led total sanitation.

Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36 (1), 191–221.

World Bank (2017). Performance of water utilities in Africa. Technical report.

World Bank (2019). Implementation completion and results report – nairobi sanitation oba

project. Technical report.

26

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: Revenue Collection Efficiency and Number of Utility Customers

2000 4000 6000 8000 10000

Number of connections

.5 .55 .6 .65 .7 .75

Proportion of total bills paid

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Date

Proportion of bills paid Number of customers

Notes. Blue line shows the proportion of payments received from total bills (in-

cluding consumption and loans) over time; Red line shows total number of utility

customers in informal settlements having either a piped water connection or both a

water and sewer connection.

Figure 2: Self-reported Reasons for Nonpayment

0% 20% 40% 60%

Payment system

was not working

Meter is

broken

I'm not responsible

for making payments

Don't

have time

Account is