University of Tennessee, Knoxville University of Tennessee, Knoxville

TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative

Exchange Exchange

Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects

Supervised Undergraduate Student Research

and Creative Work

5-2016

Black Tie Poems: An Exploration of Formal Poetry Black Tie Poems: An Exploration of Formal Poetry

Shelby Tansil

University of Tennessee-Knoxville

Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj

Part of the Poetry Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Tansil, Shelby, "Black Tie Poems: An Exploration of Formal Poetry" (2016).

Chancellor’s Honors Program

Projects.

https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1935

This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student

Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research

and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact tr[email protected].

Black Tie Poems:

An Exploration of Formal Poetry

by

Shelby Tansil

Introduction

2

It has been said that Ezra Pound’s famous poem, “In a Station of the Metro,” was

originally 30 lines long (Kennedy). But for whatever reason, Pound was unsatisfied with the

length. Eventually, he cropped it down to two lines, using a form resembling the traditional

Japanese haiku. The final product has been reprinted in countless poetry anthologies and helped

make Pound one of the best-loved modernist poets of all time. Here is the poem in its entirety:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough. (Pound)

Form plays a crucial role in the poem’s success. Somehow the brevity makes the poetic

message even stronger. The cropped form fits the fast-paced atmosphere of the metro and it

allows Pound to directly compare the image of the faces in a crowd with the image of petals on a

tree branch. Did Pound realize these formal effects at the time he was writing this? Why did he

choose to write such a short poem? Would his original, 30-line version of the poem have made it

into our contemporary literary anthologies?

I have long been curious about how poems get their forms. It fascinates me that some

poets tend to write in free verse while others tend to write in more traditional, structured forms.

And that some forms seem to work better with certain themes. Anachronisms aside, imagine if

The Odyssey had been squashed into a light-hearted clerihew, or if one of Basho’s haikus had

been stretched into an epic poem? Surely, that would have been bizarre. But why?

My senior honors thesis seemed like the perfect opportunity to explore my curiosity

about poetic form, especially because the University of Tennessee does not currently offer any

courses exclusively on this subject. It also seemed like a useful tool for improving my general

3

knowledge of poetry and my own writing. So, I decided to write a collection of poetry exploring

various poetic forms.

Ideally, I would have experimented with every poetic form in existence. Due to time

constraints, I decided to focus on nine unique forms: the acrostic, blackout poetry, the clerihew,

the ghazal, rimas dissolutas, the sestina, sijo, the sonnet and syllabic verse. From Korea to Arabia

to the United States, these forms come from a variety of cultures and poetic traditions. Their

origins date to unique time periods, ranging from the acrostic’s emergence in Ancient Greece to

blackout poetry’s much more recent appearance in the 2000’s. In addition to these forms, I also

explored the traditional meter of common measure. Please note that from now on when I use the

word “form,” I will be referring to both the aforementioned poetic forms and common measure,

even though it is not technically a form itself.

This semester, I read poems written in each of these forms, wrote my own poems, and

then discussed them with my thesis director, Dr. Arthur Smith, and my second reader, Dr. Marcel

Brouwers. During the process, I was primarily concerned with learning about the characteristics,

advantages, and disadvantages of each poetic form. I thought that by exploring these

fundamental elements I might gain greater insight into what draws poets to these particular

forms.

Before I discuss what I have learned from this process, I will explain what I consider to

be the biggest flaw in my thesis’s approach to poetic form. In order to give myself a sense of

structure, I chose to spend 1-2 weeks focusing on each form. In other words, I wrote poems in

only one style during each time period. Because I approached each poem with a specific form in

mind, my approach was somewhat unnatural. I think some of the poems feel forced into a given

style as a result. For two of these poems, “the stay-at-home skeptic” and “The Desert, My Father

4

& Me,” I have decided to include both the original version and a revised version that breaks the

form but seems to be more effective. In “the stay-at-home skeptic,” the form is only altered

slightly—though it is enough to make it no longer an acrostic poem. On the other hand, I have

completely changed the form of “The Desert, My Father & Me,” from an acrostic poem to a

prose poem. The prose poem is not one of the forms I cover in my thesis, but I decided to include

this revised version to demonstrate how dramatically form can alter the effect of a poem.

I will now walk through the forms I worked with this semester and highlight what I have

learned about their characteristics, advantages and disadvantages.

Acrostic

Origin: Ancient Greece

Scholars believe the acrostic was originally used in the “oral transmission of sacred

texts.” (Preminger). Despite these lofty origins, I associate this form with my middle school

classroom. I remember being taught how to write acrostics of my own name and the names of

loved ones. The acrostic is a great gateway poetic form for children because of its simple

structure. There is only one rule: the first letters in the lines must combine to spell out a word or

phrase.

The acrostic form can make poems more personal and convey hidden messages, which

provides a certain aesthetic appeal. However, it has one major disadvantage: it can be

distractingly obvious to readers. Thankfully, there are a few tools writers can use to make

acrostics less obvious. Frank O’Hara’s “You Are Gorgeous and I’m Coming” does an excellent

job of hiding his lover’s name: “Vincent Warren.” O’Hara uses enjambment and indentation to

disguise the form. The opening lines read:

5

Vaguely I hear the purple roar of the torn-down Third Avenue

El

it sways slightly but firmly like a hand or a golden-downed

thigh

normally I don’t think of sounds as colored unless I’m

feeling corrupt (O’Hara 1-3)

O’Hara further obscures the form by varying the capitalization at the start of each line. Many

classic acrostic poems, such as Lewis Carroll’s “A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky” and Dabney

Stuart’s “Discovering My Daughter,” capitalize all of the letters that spell out the hidden word or

phrase. The acrostic message is quickly recognized in these poems, taking away the sense of

discovery that O’Hara’s poem offers.

I mimicked the style of “You Are Gorgeous and I am Coming” in my poems, “the stay-

at-home skeptic” and “Clock Tower Peace.” Although I also experimented with a more

traditional acrostic style in “And Now, Me,” I think my Frank O’Hara-style poems are more

interesting because they require readers to engage with the poem on a deeper level.

Blackout Poetry

Origin: United States, c. 2010

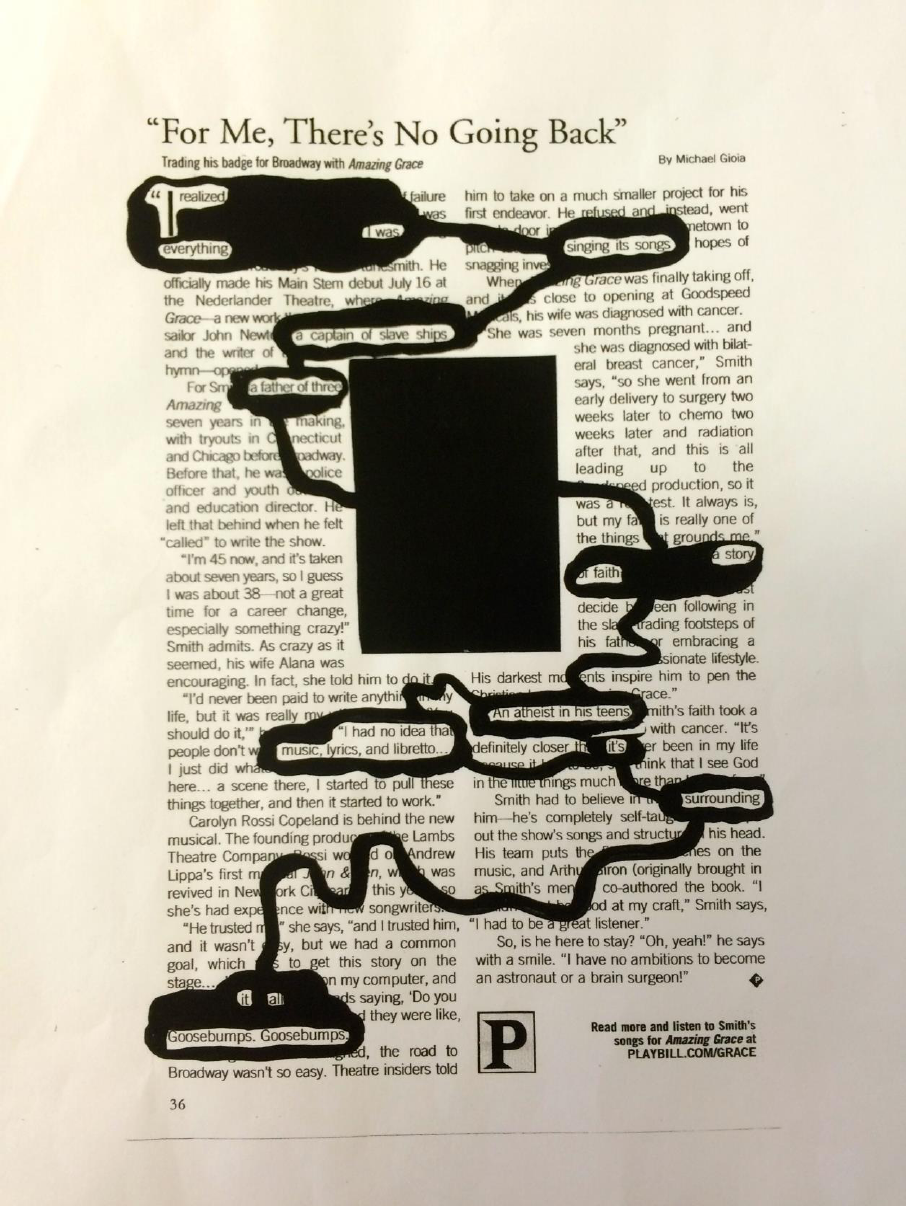

Blackout poetry is one of the latest editions to the canon of poetic form. Austin Kleon, a

cartoonist and web designer, popularized the form in 2010 with the release of his book,

Newspaper Blackout (Kleon). To write blackout poetry, find an existing text—typically a

6

newspaper—and use a permanent marker to cross out words until the remaining words form a

poem. This form has become incredibly popular on the Internet, especially on Tumblr blogs

(Kleon). Blackout poetry comes from the tradition of found poetry, which became prominent in

the 1900’s. The Academy of American Poets states:

Found poems take existing texts and refashion them, reorder them, and present

them as poems. The literary equivalent of a collage, found poetry is often made

from newspaper articles, street signs, graffiti, speeches, letters, or even other

poems. (“Poetic”)

For me, blackout poetry was even more fun to write than the comedic clerihew. The

multimedia aspect made it different from any other form I experimented with this semester.

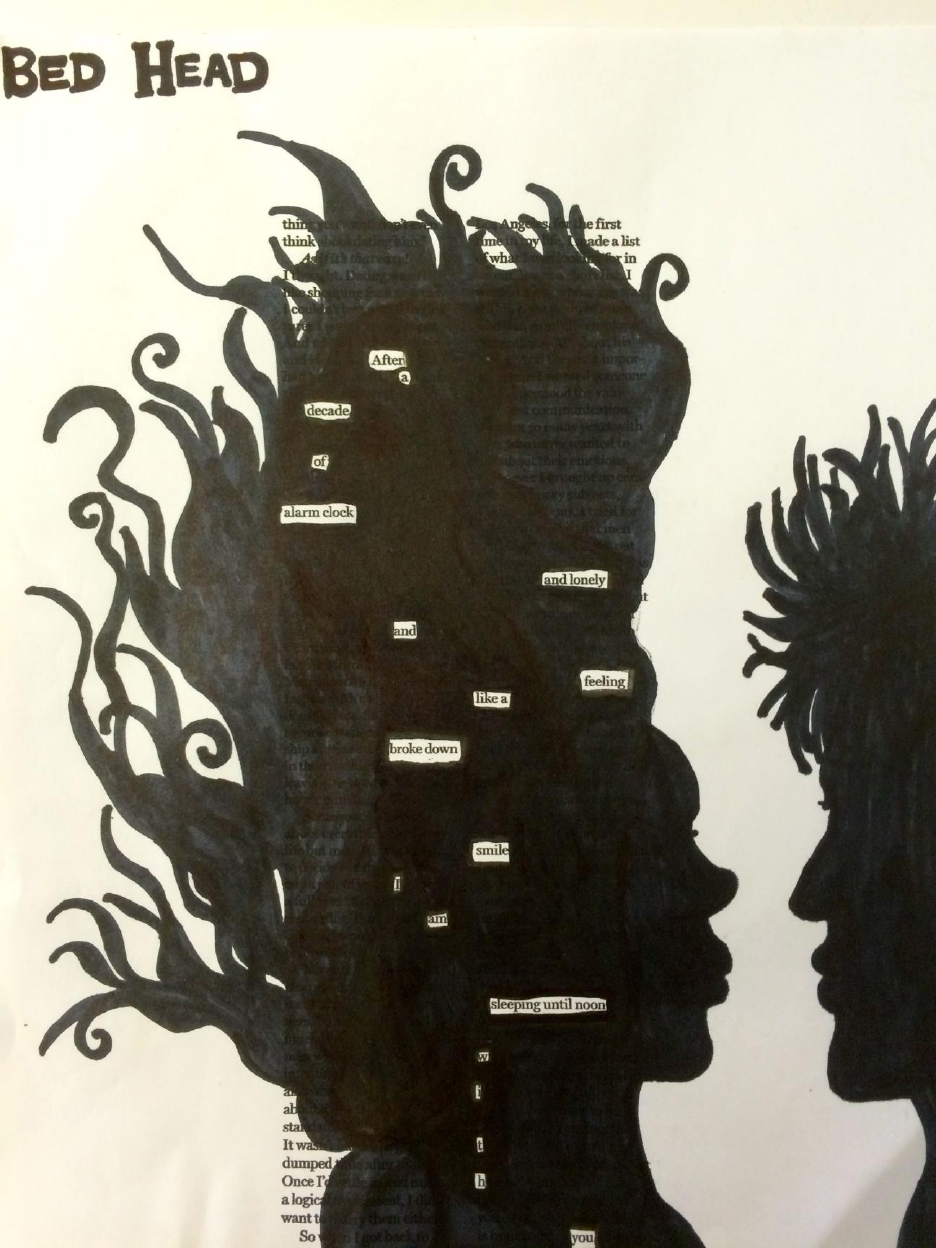

Blackout poetry also allows poets a lot of freedom in the physical presentation of poems. In my

poem, “For Me, There’s No Going Back,” the words connect like a flow chart. But in another

poem, “Bed Head,” I drew a picture of two faces around the text. Blackout poetry, like the

acrostic, can benefit a poem on an aesthetic level.

The fact that all of the words in a blackout poem must come from an existing text poses a

unique challenge. On the one hand, this is limiting to the poem’s vocabulary. On the other hand,

it pushes poets to use words they would have never considered using otherwise. I realized this

while writing “For Me, There’s No Going Back,” which closes with the unusual phrase,

“Goosebumps. Goosebumps.”

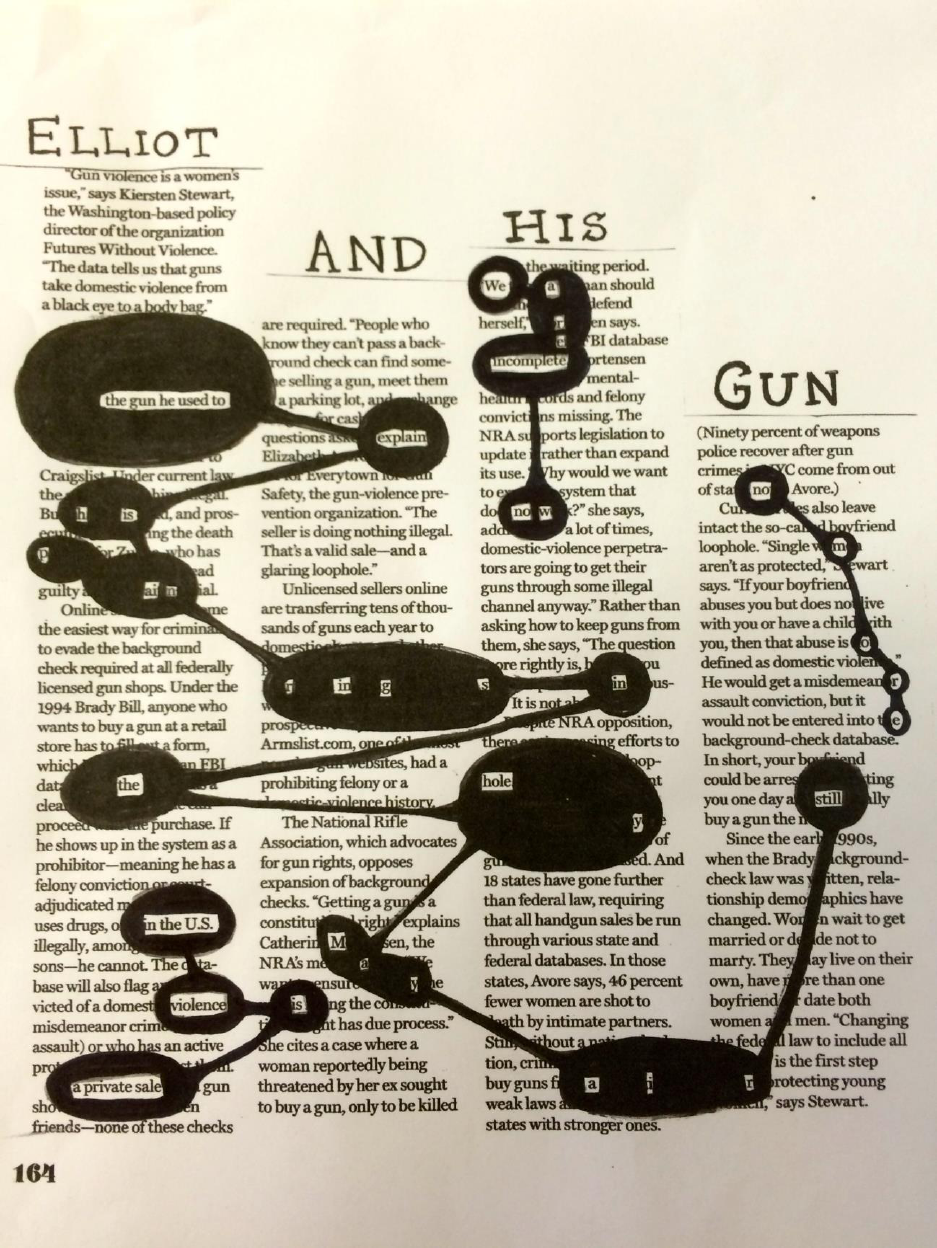

In addition to its limited vocabulary, blackout poetry can also suffer from complicated

graphics. It can be difficult to tell which direction a blackout poem reads. For example, in my

7

poem, “Elliot and His Gun,” even I will admit that it is hard to tell where to start reading. If the

font in the found text is small, or if the poet crosses out too much, it can become even harder to

read. I chose not to include some of the blackout poems I wrote because I accidentally blacked

out part of a letter or two. Note to self: Sharpie bleeds.

Clerihew

Origin: England, Early 20

th

century

Ah, the clerihew. I had quite a bit of fun working with this form. Clerihews are comical,

biographical poems, traditionally written about well-known public figures. The form was crafted

by then schoolboy Edmund Clerihew Bentley, in an attempt to entertain his friend (White 238).

The rules are simple: clerihews should be four lines in length, follow the rhyme scheme aabb,

and include the subject’s name at the end of the first line. There are no restrictions on line length

or meter, and these are often altered to create an awkward, humorous effect. This form is

intended to be playful and mocking toward its subjects.

Clerihews have several advantages. First, they are delightfully fun to write and read.

Writing in this form reminded me that there is no such thing as a proper way to write poetry. It

can be serious or silly, light or dark, deep or shallow. Second, clerihews are low investment. If I

write a crummy clerihew, it does not matter very much. I can just think of a new name and write

another poem, all within a few minutes’ time. Third, because clerihews are short and comical,

they can briefly help ease tension and provide comedic relief. Many of my thesis poems are

about death, loneliness and other heavy themes. I think the clerihew section provides a nice

moment of levity. Furthermore, the short length of this form allows readers a chance to catch

8

their breath between longer poems. Sijo, though traditionally more serious in content than the

clerihew, also has this effect because of its similarly short length.

The flip side is that the clerihew’s humor and low investment hinder its ability to tackle

more serious themes. In Poetic Meter & Poetic Form, Paul Fussell states, “Immense frivolity…is

the inseparable accessory of the four-line stanza called the clerihew, a whimsical kind of

quatrain” (Fussell 138). Even the clerihews I wanted to have more serious themes—“Candidate

Donald Trump” and “Edward Joseph Snowden”—were unable to escape the ridiculousness and

cheesiness of the clerihew.

Common Measure

Origin: Traditional hymns and ballads; Popularized in English poetry c. 19

th

century

Common measure is a poetic meter that alternates between iambic tetrameter and iambic

trimeter. Each stanza contains four lines. The rhyme scheme is abab cdcd, etc. Although

common measure has existed for hundreds of years in hymns and ballads, it is perhaps best

known in poetry circles for its frequent appearance in Emily Dickinson’s work. “Because I could

not stop for Death (479)” and “I heard a Fly buzz - when I died - (591)” are two examples of

common measure poems.

Writing in any iambic meter is tricky because as John Ridland points out, “In the

twentieth century…iambic meter has been charged with monotony” (Ridland 40). Poets writing

in common measure face an additional challenge because of its potentially distracting, sing-song

rhythm, which makes it great for hymns and ballads. To avoid monotony, poets can vary their

sentence endings (e.g. switching between enjambment and end-stopped lines), make

substitutions for iambic feet and vary their line length (41-43).

9

My poem, “The Desert, My Father & Me,” follows the common measure meter/rhyme

scheme closely, with few substitutions. This, in combination with the poem’s relatively long

length, makes the poem overly sing-songy and perhaps also monotonous. Because of this, I

decided to rewrite the poem without adhering to the common measure form. It turned into a

prose poem, which I have decided to include alongside the original version. I believe my other

common measure poem, “Confession,” is more successful because I made substitutions for some

iambic feet and varied the line length more frequently.

Ghazal

Origin: Arabia, c. 7

th

century

Like the sestina, the ghazal relies on a pattern of repeated end words. Ghazals consist of a

minimum of five couplets and have a unique rhyme scheme, which accompanies the repeated

end words. The rhyme/end word scheme was incredibly confusing to me until I read “Ghazal: To

Be Teased into DisUnity” by Agha Shahid Ali, one of the best known ghazal poets of the 20

th

century. In this essay, Ali explains,

The opening couplet (called matla) sets up a scheme rhyme (qafia) and a refrain

(radif) by having it occur in both lines. Then this scheme occurs only in the

second line of each succeeding couplet. That is, once a poet establishes the

scheme—with total freedom, I might add—s/he becomes its slave. (Ali 210)

We can see this rhyme/end word scheme at work in the opening lines of Rafique Kathwari’s

“Jewel House Ghazal”:

10

In Kashmir, half asleep, Mother listens to the rain.

In another country, I feel her presence in the rain.

A rooster precedes the Call to Prayer at Dawn:

God is a name dropper: all names at once in the rain. (Kathwari 1-4)

The refrain, “to/in the rain,” appears twice in the opening couplet and once in the subsequent

couplet. Likewise, we can see the rhyme twice in the opening couplet (“listens,” “presence”) and

once in the subsequent couplet (“once”). In ghazals, the rhyme immediately precedes the refrain.

The repeated end words/rhymes give the ghazal a musical feel, which makes sense

considering that they were traditionally sung in front of a live audience. These poems also often

appeal to a “profound and complex cultural unity,” despite the fact that each couplet is intended

to be “thematically and emotionally complete in itself” (Ali 210). If a poet is working with

subject matter related to music, culture or a specific community, the ghazal could be a great form

in which to test drive the poem. Additionally, the inherent clash between unity and disunity in

the ghazal makes it work well with contradictory or chaotic subjects.

In my poem, “Hey, College Kid,” I tried to address some of the contradictory things that

college students experience. For example, many students are simultaneously “beer-stained” (1)

and intelligent and hardworking: “You are the beautiful brain, college kid” (2). I wanted to

provide a more holistic representation of college students by highlighting the disunities among

our experiences.

The main disadvantages of the ghazal are identical to those of the sestina. The form can

distract readers, feel monotonous and give the poet a hard time, depending on which end

11

words/rhymes she picks. I found it especially challenging to commit to rhymes. Because they

must appear directly before the refrain, I struggled to find words that would make grammatical

sense. In my ghazal, “Isla Vista: May 23, 2014,” I decided to explore what would happen if I

dropped the rhyme scheme but kept the pattern of end words. Dropping the rhyme scheme gave

me more freedom, but it also took away some of the poem’s musical quality.

Rimas Dissolutas

Origin: France, c. 12

th

-13

th

centuries

In this form, “each line of a nonrhyming stanza (which may be of any length) rhymes

with its corresponding line in subsequent stanzas. For example, a three-stanza poem in four line

stanzas would rhyme abcd abcd abcd” (Dacey 440). This form is intended to be written in

isosyllabics—meaning that all lines have the same syllable lengths.

In an age where rhyme seems to have fallen out of fashion, rimas dissolutas seems like

the perfect hybrid of rhyme and contemporary preference. The rhymes are subtle—and

sometimes even unnoticeable—because of the distance that lies between them. This produces a

beautiful echo effect between the different stanzas.

The downside to this form is that it can be difficult to keep up the intricate rhyme

scheme. In my poem, “Takeout Night,” I struggled to find a rhyme for the fourth line in each

stanza. To keep the poem as close to the meaning I intended, I eventually re-used the word,

“going,” in the final line, despite my desire to make each end word unique. Additionally, I

significantly altered the rimas dissolutas form in my poem, “What I Learned from the Cooks.”

Instead of maintaining the same rhyme scheme throughout the entire poem, I wrote a series of

12

paired stanzas that each share a rhyme scheme. In this manner, the poem is more like a series of

connected rimas dissolutas poems than it is like a single unified rimas dissolutas poem.

Sestina

Origin: France, c. 12

th

century

The sestina was the most challenging form I tried this semester. It consists of six sestet

stanzas, followed by a three-line envoi. Repetition is paramount in this form, with the same end

words used in each sestet stanza, but in a unique order. Typically, the envoi also uses these same

end words, with two in each line.

The primary downsides to the sestina are clear: 1) it is a hassle to get all of the end words

in their proper positions, 2) the lines risk becoming monotonous and 3) the form can distract the

reader. In his essay, “Sestina: The End Game,” Lewis Turco suggests that poets can avoid

monotony and distraction by using enjambment, as well as homographs and ploys (e.g. “can and

toucan) for the end words. (Turco 291). Another issue, which I had not considered until I began

experimenting with sestinas for myself, is that it can be difficult to choose the right end words. In

my sestina, “Father America,” I backed my imagination into a corner by choosing to include the

end word, “blanket.” Not that the word could not work well in another poem, but it is perhaps

too far flung from the context of the poem to naturally use seven times. The next time I write a

sestina, I will make sure to brainstorm words for a while, instead of rushing into the structure

with the first six words that seem halfway decent.

If sestinas are such a hassle, why write them? When it is functioning properly, I do not

think there is any poetic form as beautiful or entrancing. The rhythmic repetition is almost

13

hypnotic. Peter Cooley’s “A Place Made of Starlight” uses the sestina form to suck readers into

the atmosphere of the poem. In the opening stanzas, he writes:

This is the woman I know to be my sister.

Wizened, apple-sallow, she likes her room dark

inside the nursing home’s glare. She barely sees me,

black shades drawn against the radiant autumn day,

purple, hectic yellow streaming from the trees.

I stand and stare. One of us has to speak.

How are you? FINE. Why did I try to speak

as if we could talk, a brother and a sister

perched on the same branch of our family tree?

We share our parents. But the forest, suddenly dark,

dwarfs me always, now I’m here, where I see me,

fifty years back, ten years younger, even today. (Cooley 1-12)

By using the end words, “dark” and “trees,” Cooley creates an ominous, forest-like

setting. This dark setting becomes inescapable due to the repetition that occurs in the sestina

form. As a result, readers experience the same trapped feeling as the speaker of the poem. The

sestina is a useful form for writing about themes involving entrapment of a physical or

psychological nature.

14

Sijo

Origin: Korea, c. 14

th

century

Like the ghazal, sijo is traditionally sung to music. Today, sijo still has a strong presence

in Korea. Sijo practitioners, young and old, sing the poetry to the beat of a folk drum. Some

schools require children to memorize sijo and rural farmers use scrolls of it as wallpaper to

decorate their homes. Classic sijo themes include: country life, nostalgia, love and scenes of

ordinary life (Rutt). The form is composed of three lines, each of which contains 14-16 syllables.

Tap Dancing on the Roof: Sijo (Poems) explains the traditional purpose of each line: “The first

line introduces the topic. The second line develops the topic further. And the third line always

contains some kind of twist—humor or irony, an unexpected image, a pun, or a play on words”

(Park). This structural format makes the sijo feel somewhat like a condensed sonnet.

The most challenging aspect of the sijo for me was achieving a line length of 14-16

syllables. I generally do not write such long lines in my poetry. Though the other poems I wrote

follow the appropriate meter, “Apple of My Eye” contains only 13 syllables in the first line and

11 syllables is in the final line. However, because the poem invokes the traditional sijo themes of

love and nature and includes a twist in the final line, I think it can still be categorized as sijo.

Sijo’s sonnet-like structure makes it a great form for addressing questions or multiple

perspectives on a topic. The tradition of writing sijo about country life makes it a meaningful

format for reflecting on powerful natural imagery. We can see all of these elements working

together in the following sijo from U T’ak (1262-1342):

The spring breeze melted snow on the hills, then quickly disappeared.

I wish I could borrow it briefly to blow over my hair

and melt away the aging frost forming now about my ears. (T’ak)

15

Sijo is similar to the haiku: short, but powerful. The poet throws readers into the poem, hits them

with an image and then immediately yanks them back out.

Sonnet

Origin: Italy, c. 13

th

century

There are two major types of sonnet: the Petrarchan (Italian) sonnet and the

Shakespearean (English) sonnet. Petrarchan sonnets contain fourteen lines, which are divided

between an octave and a sestet. These poems are traditionally written in iambic pentameter with

the rhyme scheme: abbaabba cdecde or abbaabba cdcdcd. Shakespearean sonnets are also

written in fourteen-lined iambic pentameter, but they use a different stanza form and rhyme

scheme. These sonnets have three quatrains, followed by a rhyming couplet. The rhyme scheme

is: abab cdcd efef gg. Despite these variations, sonnets written in both forms present their poetic

messages in the same way. They use a narrative structure in which a problem is presented,

complicated, and then responded to or resolved. In Petrarchan sonnets, the octave and sestet have

“clearly defined rhetorical roles. Stanza 1 (the octave) presents a situation or problem that Stanza

2 (the sestet) comments on or resolves” (Williams 80). In contrast, the first eight lines of a

Shakespearean sonnet present an issue that is “dealt with tentatively in the next four lines and

summarily in the terminal couplet” (82). These sudden shifts in perspective can have a jarring

impact on readers.

One poem that uses these perspective shifts to its advantage is Keats’ Shakespearean

sonnet, “When I Have Fears.” In this poem, the narrator uses the first three quatrains to list his

fears: “that I may cease to be / Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain” (Keats 1-2),

16

“When I behold, upon the night’s starred face, / huge cloudy symbols of a high romance, / And

think that I may never trace / their shadows” (5-8) and “That I shall never look upon thee more”

(10). The speaker’s fears shift from the broad idea of death, to the idea of lost romance to the

idea of losing a specific person. The issue becomes more precisely defined as the poem

progresses, as is characteristic of Shakespearean sonnets. Yet we do not see how these fears

impact the narrator until we reach the concluding couplet: “Of the wide world I stand alone, and

think / Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink (13-14). The sonnet asks the question: What

happens when I have fears? But it does not answer right away; instead it continues to list the

speaker’s fears, causing the tension to build until the poem’s final moment. This procrastinated

response gives the sonnet a unique sense of angst and intensity.

Because of these qualities, I find the sonnet to be a great form for exploring topics that

bother me and things that I cannot understand. For example, my Petrarchan sonnet, “In Memory

of You(r Hair),” grew from questions I had related to a high school classmate’s suicide. Was he

depressed? Why did his death impact me so much when I did not know him personally? Why

weren’t we friends? Why could I only remember his physical features? This mixture of curiosity,

shame, angst and sadness transitioned somewhat easily into a sonnet. The form also seems

suitable for “In Memory of You(r Hair)” because the poem features a major shift in tone between

the octet and the sestet. Between these two stanzas, the focus shifts from the shallowness of the

speaker’s relationship to the “You” character to a deeper consideration of the “You” character’s

death.

I struggled with other aspects of the sonnet. Although the narrative structure can have a

jarring impact on the reader, it can also feel obvious. In my poem, “Progress,” this method is

obstructively obvious. Between the octet and sestet, there is a shift in tone, a literal blank space

17

and a break in the anaphora of “There have always been.” These combined elements make the

sonnet form stick out like a sore thumb. Here, form takes precedence over content, which risks

inhibiting the poetic meaning. Writing sonnets has taught me that forms tend to work the best

when they are not obvious.

Syllabic Verse

Origin: England, c. 20th century

Syllable count plays an important role in many Eastern and Western poetic traditions, but

I decided to focus solely on English syllabic verse. Unlike other syllable-counting forms, this

form does not have restrictions on accent or meter. There is only one rule in syllabic verse: there

must be the same number of syllables in corresponding lines of all stanzas (e.g. the 1

st

line of

every stanza must have the same number of syllables, and so forth).

Margaret Holley’s essay, “Syllabics: Sweeter Melodies,” highlights some of the main

disadvantages of syllabic verse. One issue is that poems can begin to feel robotic and

monotonous if the lines containing the same syllables also have similar metrical patterns. Holley

suggests using lines with odd numbers of syllables to prevent this from happening (Holley). I

experienced trouble with the numerical aspect of syllabic verse. When I first started writing in

this style, I counted on my fingers as I went along. I was so focused on the syllable count being

perfect that I put the content on the back burner. This is apparent in “We want our buildings,”

which was the first syllabic poem I wrote. Despite the poem’s short length, it is filled with

uninteresting, one syllable filler words like “and” and “the.”

I had more success in later syllabic poems, such as “Love in Boxes.” For this poem, I did

not count obsessively while I was writing it, but instead went back and altered lines after most of

18

it was written. Syllabic verse also works well in this poem because of how the stanzas are broken

up. I think the transition between the sixth and seventh stanza is particularly effective:

when you are carefree and singing

hip-hop songs in

your pickup truck, on

the road to nowhere

you have to be. I want for you

to always feel

that free. And if my

hand feels like a trap (21-28)

These stanzas seem like complete ideas, but they also build off of each other. The truck is both

“on / the road to nowhere” and “on / the road to nowhere / you have to be.” Here, syllabic verse

adds complexity to the poem. This form works best when poets focus not just on syllable count,

but also on word placement.

After studying and writing in these diverse poetic forms, I have come to a couple of

conclusions. First, it is difficult for a poem to succeed when any form is forced upon it. Because

each form has unique characteristics, some poems work well as acrostics. Some work well as

sestinas. Others do not work well in either form. I only provided post-formal versions of my

poems, “the stay-at-home-skeptic” and “The Desert, My Father & Me,” but I think many of my

19

other poems could also benefit from further altering or breaking of their forms. The most

important lesson I learned this semester is how to be more flexible with my poetry. I am now

giving myself permission to let a sonnet become a haiku and to let a free verse poem turn into a

sestina. I structured my thesis so that I was writing toward a form each week, and I have learned

that this method does not work for me. Poetic form should not be the poem’s destination; it is

merely a vehicle that helps the poem get there.

Only two of the poems I wrote this semester did not begin with an end form in mind: “In

Memory of You(r Hair)” and “Love in Boxes.” While I was part of the way through writing

these poems, I recognized characteristics that they shared with specific forms. “In Memory of

You(r Hair) came out in rough iambic pentameter and was broken up into two narrative sections,

like a Petrarchan sonnet. The first two stanzas of “Love in Boxes” came out approximately in

syllabic verse. In both of these poems, the forms developed almost naturally. I do not think it is a

coincidence that these are two of my stronger poems. I believe they work well in large part

because the forms work. From my experience, poetic form is more likely to succeed when it

emerges after the writing process begins.

But the only reason these poems were able to develop somewhat naturally is that I knew

the main characteristics of the poetic forms I ended up using. Reading formal poetry and books

on poetic form taught me this information. For poets interested in writing in form, it is crucial to

read a variety of poems written in these styles. All forms have unique rhythms, rhyme schemes,

syllable counts, etc. Being able to recognize these characteristics in another poet’s work makes it

possible to recognize them in one’s own work. Another benefit to reading formal poetry is that

we can learn tricks from other poets. When I was writing acrostic poems this semester, I relied

on Frank O’Hara’s techniques to help me disguise the form. When I was creating blackout

20

poetry, I experimented not just with blacking out words, but also with drawing pictures around

them. This is a method I saw used among some of the poems I read.

A final lesson I learned is that altering the form or breaking the rules can actually make a

poetic form more effective. If the iambic meter in a poem is becoming monotonous, the poet can

vary the line length. If a poem is written in syllabics, varying the number of syllables in a few

lines can have an interesting, dissonant effect. Formal poetry is often seen as more restrictive

than free verse, but I would argue that there is far more freedom here than meets the eye.

Bibliography

Ali, Agha Shahid. "Ghazal: To Be Teased into DisUnity." An Exaltation of Forms. Ed. Annie

Finch and Katherine Varnes. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2002. 210-216. Print.

Anderson, Jon. "The Blue Animals." Strong Measures: Contemporary American Poetry in

Traditional Forms. Ed. Philip Dacey and David Jauss. New York:

21

HarperCollinsPublishers, 1986. 17. Print.

"Common Measure." The Poetry Foundation. N.p., n.d. Web.

Cooley, Peter. “A Place Made of Starlight.” A Place Made of Starlight. Pittsburgh: Carnegie

Mellon.

2003. 27-28. Print.

Dacey, Philip, and David Jauss, eds. Strong Measures: Contemporary American Poetry in

Traditional Forms. New York: HarperCollinsPublishers, 1986. Print.

Fussell, Paul. Poetic Meter & Poetic Form (Revised Edition). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Print.

Kathwari, Rafique. "Jewel House Ghazal." An Exaltation of Forms. Ed. Annie Finch

and Katherine Varnes. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2002. 214. Print.

Keats, John. "When I Have Fears." Ed. R. S. Gwynn. Poetry: A Pocket Anthology. 6th ed. New

York: Pearson Education, 2009. 130-131. Print.

Kennedy, X. J. An Introduction to Poetry. 3rd ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974. Print.

Kleon, Austin. Austin Kleon. N.p., n.d. Web.

Holley, Margaret. "Syllabics: Sweeter Melodies." An Exaltation of Forms. Ed. Annie

Finch and Katherine Varnes. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2002. 24-31. Print.

O'Hara, Frank. "You Are Gorgeous and I'm Coming." Strong Measures: Contemporary

American Poetry in Traditional Forms. Ed. Philip Dacey and David Jauss. New York:

HarperCollinsPublishers, 1986. 254. Print.

Park, Linda Sue. Tap Dancing on the Roof: Sijo (Poems). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

2007. Print.

"Poetic Form: Found Poem." Poets.org. Academy of American Poets, n.d. Web.

22

Pound, Ezra. "In a Station of the Metro" Modern American Poetry. Ed. Louis Untermeyer.

New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1919; Bartleby.com, 1999.

Preminger, Alex, ed. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition.

Princeton: Princeton UP, 1974. Print.

Ridland, John. "Iambic Meter." An Exaltation of Forms. Ed. Annie Finch and Katherine Varnes.

Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2002. 210-216. Print.

Rutt, Richard, ed. The Bamboo Grove: An Introduction to Sijo. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 1998.

Print. Ann Arbor Paperbacks.

T'ak, U. Trans. Larry Gross. N.p.: n.p., n.d. The Sejong Cultural Society. Web. 1262-1342.

Turco, Lewis. "Sestina: The End Game." An Exaltation of Forms. Ed. Annie Finch

and Katherine Varnes. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2002. 290-296. Print.

White, Gail. "Form Lite: Limericks and Clerihews." An Exaltation of Forms. Ed. Annie Finch

and Katherine Varnes. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 2002. 238-241. Print.

Williams, Miller. Patterns of Poetry: An Encyclopedia of Forms. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

UP, 1986. Print.

Note: In the blackout poetry section, I used existing texts as the source material for each of my

poems. The following is a list of my blackout poems along with a citation of the found text I

used in each one.

1) “Bed Head”

23

Havrilesky, Heather. "What You Should Really Look For in a Guy." Cosmopolitan Mar.

2016: 144. Print.

2) “Elliot and His Gun”

Welch, Liz. "Love and Guns." Cosmopolitan Mar. 2016: 164. Print.

3) “For Me, There’s No Going Back”

Gioia, Michael. "For Me, There's No Going Back." Phantom of the Opera Playbill (2016): 36.

Print.

THE ACROSTIC

AND NOW, ME

Balloons, candy-colored and limping in the sun,

Rickety push carts of aguas frescas,

Orthodox Jews quietly returning home under streetlight,

Off-brand snacks crackling open,

Kids racing through Laundromats, their parents

Loading shiny quarters into the machines, sighing,

24

Yellow flowers peeping through sidewalk cracks and

Nobody waiting for the Sunday train.

THE STAY-AT-HOME SKEPTIC

*original version

any time lightning bugs float between

fire hydrants and stray cats,

god a prettier picture seems, and he

dances in me like light through stained glass

25

now what could these wandering stars

possibly be doing on my doorstep?

other times, I am opening a pickle jar

and the lid makes a small pop

somehow the line “everything is in god’s plan”

excites me more than ever

the earth was created so my hands

could open Vlasic jars, how clever!

is there anything more god-inspiring

than the beautiful bizarre?

churches can’t light my faithfire

but answerless questions take me far.

looking at pickle jars and lightning bugs,

my heart squints, in search of god’s face

only I’m distracted by barcodes, insect legs

and the heavens slowly evaporate. I

view eternity from my front door,

put on my Sunday shoes, but

eternity is too cloud white for me

I find my sanctuary in the Sunday news.

THE STAY-AT-HOME SKEPTIC

*revised, post-acrostic version

any time lightning bugs float between

fire hydrants and stray cats,

god a prettier picture seems, and he

dances in me like light through stained glass

26

now what could these wandering stars

be doing on my doorstep?

other times, I open a pickle jar

and the lid makes a small pop

somehow the line “everything is in god’s plan”

excites me more than ever

the earth was created so my hands

could open Vlasic jars, how clever!

is there anything more god-inspiring

than the beautiful bizarre?

churches don’t light my faithfire

but answerless questions take me far.

looking at pickle jars and lightning bugs,

my heart squints, in search of god’s face

but I’m distracted by barcodes, insect legs

and the heavens slowly evaporate.

CLOCK TOWER PEACE

If you pay a small fee, you can tour the Bath Abbey

and spy on the choir through ceiling cracks.

Near sweaty tourists, you can scale the steps,

which are misshapen like a heart.

Somewhere in the dark, the clock tower waits

to meet a crowd of new faces.

27

On nights like this, I long to be in the Abbey clock

where the gears silently stir the air.

My wristwatches sit on the bureau, counting stars.

These walls echo their tick-tocks, which

Never stop to catch their breath. It’s as if

I am living inside their sound.

I am always awake this time of year

when work feels long and days feel short.

Airplane tickets are not cheap, but maybe

it would be worth it to fly there and

Crawl into the clock tower’s open hands.

Maybe then I could finally sleep.

BLACKOUT POETRY

28

29

30

31

THE CLERIHEW

The dog named Rosie

had an awful long nose-y

which she used to sniff socks

and unsuspecting buttocks.

32

Edward Joseph Snowden

He’s in Russia, snowed in

Leaked government information

To save us from our nation.

33

I AM CAPSLOCK

I POUND, I DO NOT KNOCK

ON YOUR COMPUTER SCREEN

MY BEST FRIENDS ARE FEMALE TWEENS

34

Candidate Donald Trump

Another GOP cancerous lump

Flares up hate like an angry pimple

But filling hotel rooms was never so simple!

35

COMMON MEASURE

THE DESERT, MY FATHER & ME

*original version

“I love these New Mexico skies,”

my father says to me.

“The clouds are special, don’t you think?”

I tilt my head to see.

There’s something odd about the way

they stretch across the blue

As if scrawled by some carefree hand

that had nothing to do.

I nod my head. “They’re beautiful.”

Then silence kicks back in.

One hundred miles or so today,

our words are wearing thin.

My father, me. We’re great with words

when written on a page.

But here in human company,

our voices disengage.

Between my windshield wiper toes

the desert never ends,

in spite of shrubs that green the brown

and parasite the sands.

I wonder why he loves this scene

until I can recall:

He grew up in some Texas town.

He learned the desert’s crawl.

For every fact I know about

his past, I don’t know three.

I want to know his hangout spot

when he was a child, wild and free.

A few miles back we passed a town,

along route 66.

American dream built that town,

but it had gotten sick.

36

Abandoned buildings, broken glass

and faded product ads

for things that no longer exist.

The town was aged and sad.

To my surprise, people lived there

in small forgotten homes.

They walked and talked as people do

and did not seem alone.

My father’s past is like that town,

he’s almost let it die.

But there is beauty hidden there,

I find it when I try.

37

THE DESERT, MY FATHER & ME

*Revised, prose poem version

We are driving through the New Mexican desert when my father says something about the

clouds. I press my nose to the window, exhaling a small cloud of my own. This sky doesn’t

interest me. Tell me how the clouds looked when you tasted your first kiss. Tell me how they

looked when you were eight years old, sneaking cherry tomatoes from your mother’s garden

while her back was turned. Tell me how they looked after you stopped believing in God. Still, I

am thankful when you say anything at all. Words fall between us, precious and rare as desert

rain.

38

CONFESSION

Because I am not brave enough,

my love is made of paper.

A love that’s easily torn up

or kept inside a drawer.

I am scared to write your name,

so your shadow slinks alone

between printed words, claiming

metaphors for its own.

If you should ever read these poems,

you won’t know who you are.

I’ve made you into anyone.

That’s my worst crime by far.

39

THE GHAZAL

HEY, COLLEGE KID

You are the bloodshot, beer-stained college kid

You are the beautiful brain, college kid.

Swallow your expired Ibuprofen

Hangovers pound like a train, college kid.

Football Saturday, orange and white war paint.

Oh shit. Forecast predicts rain, college kid.

Stutter through public speech, study through night

Sleep now or you’ll go insane, college kid.

Five-dollar movies, cheap shirts and koozies

Free fitness classes—go train, college kid.

Salad bar has it all: peas, croutons, corn,

But beware of that chow mein, college kid.

Hours on laptop—doing work, watching porn

Take a break to fight eyestrain, college kid.

If you ache for home or always feel alone

Please reach out—don’t live in pain, college kid.

Use skillets for umbrellas, t-shirts for towels

Creativity is off the chain, college kid.

Forget those fools; the best years await you

Life’s not down the drain after college, kid.

40

ISLA VISTA: May 23, 2014

We were getting trashed like a wet lawn newspaper.

Vodka stained my mind—spilt ink on newspaper.

Sorority girls walked home from class.

Locals bought convenience store newspapers.

A few streets away, he exited the car.

Black semi-automatic in white hand: newspaper

colors. We ran outside because it sounded like fireworks

breaking the dark, the way stories break in newspapers.

The next morning we sank in the couch, watching

the nights’ events on every TV, in every newspaper.

Seven dead. His guns and knives

sliced open their skin like sharp-edged newspapers.

The living room smelled of alcohol and fruit punch.

Our mouths opened and closed like newspapers.

41

RIMAS DISSOLUTAS

TAKEOUT NIGHT

Plastic bag of takeout food, crumpled receipt, keys in hand.

Night air smells of gasoline and something I cannot name.

I walk past a kid my age—ear gauges, bed head, alone.

Our eyes meet. Does he also wonder where I am going?

The apartment is a dirty, inanimate wasteland

Of crusted on frying pans and dusted on window panes.

I eat with my fingers, sit on the floor,

Listen to the sound of eyelids opening and closing.

Outside, students are stepping in time to their private bands.

Music can drown out thoughts in even the noisiest brain

And it almost feels like a hug—the ears in the headphones.

Maybe they are all hearing the same song without knowing.

My roommate returns and tells me about her weekend plans.

She is the gust of wind to my old fashioned weathervane:

Stirs me from loneliness, that dull feeling which has shown

Itself over the years, like the crow’s feet growing

Next to my eyes. I age myself from the inside out and

I am bitter as the child who loses a game.

But the only one here to blame is this heart of my own.

It stays silent when I ask where I’m going.

42

WHAT I LEARNED FROM THE COOKS

Two summers of working in a kitchen

with well-seasoned cooks

taught me more about love

than any corny romance flick.

No rain-soaked caress

could match their reverence for food

or produce such milk white smiles.

They were positively smitten

(you could tell by one look)

with the ripe thump of

melon or a honey-thick

glaze. And they loved no less

to see the different hues

in an heirloom tomato pile.

Even carrots that bent like witches’ fingers

and gallon tubs of mayonnaise

were treated with respect.

And maybe they were loved more

because of their grotesque nature.

Memories of the summer kitchen linger

as years are lovingly spun from days.

Again and again I resurrect

How their hands opened like doors

to welcome culinary friend and stranger.

Food is not just fuel or taste;

it has a sound, rhythm and touch

in the hands of those who love it.

In the kitchen, I was a novice fool,

I’m not afraid to admit that much.

But I loved to see them covet

every inch of those earthly creations—

it was a love that made altars of food stations.

43

THE SESTINA

FATHER AMERICA

The founding fathers

Spread their legs and gave birth

to a ruddy-faced America.

It howled into the bright room

Of the world

And soiled its blanket.

America slept under a blanket of

Stars stolen from another’s fathers.

The Old World

Sighed. A stolen brat from birth,

The child always asked for more room.

Nothing was enough for America.

But America

Wasn’t a bad kid. It shared its stolen blanket

And left others sleep in its large bedroom.

It welcomed children, mothers, fathers

Of different religions and social births.

It said, “Let’s make this home our world.”

“I’ll make this world

my home,” shouted teenage America.

It glared, shoved, gave no one a wide berth.

America wore combat boots, blanketed

Bodies and fatherlands

In chemical dust and empty rooms.

Is there room

In this world

For a self-proclaimed father

figure like America?

My mind goes blank. It

Seems odd to be a father so soon after birth.

240 years have passed since its birth.

America is young and has much room

To grow up. On the blanket

Of the world,

A mere stitch is America,

Threaded by its forefathers.

44

Birth follows birth, sons become fathers

The world becomes a small room.

America clings to the past like a warm blanket.

45

SIJO

APPLE OF MY EYE

I slice memories of you into bite-size pieces

And suck on the sweet juice. The sugar tingles on my taste buds.

Tell me where our tree grows, if it still bears fruit.

46

EARTH SONG

The same rain may fall on our heads,

but not the same raindrops

The same sun may warm our bodies,

but we burn differently

The same ground may hold our feet,

but we leave only our own prints

47

IN THE DARKROOM

Under the pale glow, I lower paper into liquid.

Your wrinkled hands emerge and stain the whiteness of the page.

To be the space between your fingers, which knows loneliness.

48

MIDNIGHT IN GALWAY

The man under the moon drags his soul across his bowstrings.

Drunk, carrying their heels, girls spill out of pubs to listen.

They toss euros into his case, crying, “Play us another!”

49

MY GRANDFATHER AT TWO YEARS OLD

His mother’s death was a black city car, a man in a cheap suit.

His grief was walking through cornfields in a dirty diaper.

Not even the wind raised its voice to ask where he was going.

50

THE SONNET

IN MEMORY OF YOU(R HAIR)

For Shane

The truth is, I knew you mainly

by your hair. It always looked soft, like fountain

grass. I wonder what shampoo it wore each

day. Perhaps it smelled of mint or fresh leaves?

My friends and I would whisper when you walked

into our classroom. Hearts beating faster,

and all because we really loved your hair.

We were that high school brand of shallow.

I wonder if you ran your fingers through it

before you pulled the trigger. Did you

cry and did that wet the blonde like unheard

rain? If I could go back in time, I would.

To learn the way your thunder sounded and

brush away the thoughts that tucked you into sleep.

51

PROGRESS

There have always been people wailing in the street,

teenagers raped by mutual friends,

minorities warred on again and again

and poor folks licking boots of the elite.

There have always been people singing in the street,

perfumed love letters to send,

blackberry-picking at summer’s end

and infants stumbling onto first feet

We are always saying the word “progress,”

referencing some distant past.

We laugh at the Neanderthal

special featured on PBS.

“What brutes, thank God they didn’t last!”

Up next: Police kill black boy in brawl.

52

FAT GIRL EATING JELLY BEANS

I admit I have been eating jelly beans.

My fingertips are Cotton Candy pink,

sticky like my sweating thighs,

which are Cryovaced into jeans.

Yeah, I shouldn’t be eating them.

Shut the fuck up, brain.

They remind me of summertime

and my mom’s laughter, okay?

What else do you want me to say?

Depression is eating me up inside

and I need junk food to get through today?

I bet it’s something along those lines.

It’s true that I’m addicted to the taste and feeling.

But listen, sometimes jelly beans are just jelly beans.

53

SYLLABIC VERSE

WE WANT OUR BUILDINGS

but we scoff

at safety vests

and orange hard hats.

As soon as

the cranes roll in and the

boards are piled,

you can hear

the residential sigh

settling in.

We loathe the

hammers, the drills, the nails.

How will we sleep

in our beds

or enjoy a quiet

dinner at the

kitchen table?

54

AT ANY MUSEUM IN THE WORLD

Remember Amsterdam?

Disoriented

by flowered bikes and foreign language,

your eyes swung

between the pavement and the constellations,

which you could not trust

because even the sky

was different

from home.

But we spent three hours

in the Rijksmuseum

breathing in ancient books, clean floors and

forgotten

oil paintings by Dutch artists who killed them-

selves. Your happy place.

And it was okay that

we did not

know how

to order sandwiches

or say “Good evening”

because art was the same everywhere

because all

over the world, ideas were moving artists,

artists were moving

their hands, people were moving

through rooms just

like us.

55

LOVE IN BOXES

I am sorry for loving you

nostalgically.

You are a person,

not a photograph.

I cling to the colors of our

laughter (balloon

gray, popcorn yellow).

They fade to off-white

at my useless touch. I blamed you

at first—it’s true.

Wanted to keep you

growing by my side

forever. Like two willow trees

who shake their leaves

and weep together

and age in the sun.

But I cannot root you to my

ground. And I would

not want to either.

You are most lovely

when you are carefree and singing

hip-hop songs in

your pickup truck, on

the road to nowhere

you have to be. I want for you

to always feel

that free. And if my

hand feels like a trap,

let it go. I have loved you with

nostalgia—please

forgive me for this.

I was not prepared

for you to leave the pages of

my albums. But

you are still here and

I will try to love

56

you in this moment, even if

it hurts a bit

to know our friendship

lives in an old box.