DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 281 369

FL 016 646

AUTHOR

.

Barnwell, David

TITLE

Syntactic and Morphological Errors of English

Speakers on the Spanish Past Tense .

PUB DATE

[87]

NOTE

24p.

PUB TYPE

Reports - Research/Technical (143)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC01 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

College Students; Comparative Analysis

Contrastive

Linguistics; *Error Patterns; Higher Education;

*Interference (Language); Morphology (Languages);

Second Language Learning; *Spanish; *Syntax; *Tenses

(Grammar); *Verbs; Writing (Compositio.1)

IDENTIFIERS

*Past Tense

ABSTRACT

A study examined the patterns of error in the

preterite and imperfect tenses in the written Spanish of native

English-speaking college studentg. Errors found in the midterm

examination were analyzed to determine whether they were due to

incorrect tense, incorrect form of the tense, or both. It was

predicted that many students would choose incorrect form or tense,

and many more would choose both. Results revealed that very few

answered with both incorrect tense and incorrect form, suggesting

that the choice of verb tense and knowledge of correct form are

largely independent of each other. In addition, interlingual errors

(choice of tense) were slightly more common than intralingual errors

(choice of verb form), supporting some earlier research results.

(MSE)

***********************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

from the original document.

***********************************************************************

SYNTACTIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL ERRORS OF ENGLISH SPEAKERS

ON THE SPANISH PAST TENSES

David Barnwell

Columbia University

-11.8.-DEPARTNENT OF EDUCATION

Office 04 Educational Research and Improvement

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

Irf.frus document 1126 been

reproduced as

recetved_trom the person or organization

originating

it

0 Minor changes have been made to improve

reproduction quality.

Points of view or opinions stated

in thia docu-

ment do not

necessarily represent official

OERI position or policy

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

12

"PERMISSION TO_REPRODUCE THIS

MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED

BY

onvddi

TC1THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)."

a

SYNTACTIC

AND

MORPHOLOGICAL ERRORS OF ENGLISH SPEAKERS

ON THE SPANISH PAST TENSES

Introduction

The

coalesced category represented by the English past tense

is

split

in Spanish.

Choice of aspect,

an element

which

is

expressed in

English through

the

choice_ of

simple

versus

progressive

tenses

(completed <> not completed) is more

often

realized

in Spanish

by means

of the

imperfect/preterite

distinction.

Detailed

contrastive

analyses

of

the Spanish

preterite/imperfect

versus the English past may be found in BuIl

(1965) And atockwell et al.

(1965).

The extensive coverage

of

the

topic provided by these authorities corraborates what

every

teacher of Spnish to English speakers knows from experience--the

contrast

between the

languages

treatment

of

peat events,

conditions'

etc.,

is a major source of difficulty to

learners.

However,

as will be seen later,

contrastive analysis does not

always succeed in predicting the difficulties faced by learners.

This study attempts to investigate patterns of errors in the

preterite

and

imperfect in the written Spanish of

students of

Epanish II at

the University of Pittsburgh.

It does so through

an empirical investigation

of the kinds of errors these students

Made on

their Midterm exam.

(The exam was held in

1983this

report

could

not

be released up to now

for reasons

of

exam

Security)

,3

It

is

probable

that different

instructors

explain the

Spanish tense system in different ways, but the basic explanation

put

forward in the text used at Pitt was likely to be the common

foundation

upon

which the subjects of this study

depended for

guidance in

this area.

So I consider it useful

to

cite the

exposition of

the preterite/imperfect with which

nearly

every

student of Spanish II included in this study might be expected to

be familiar:

EsGentially, the preterit

Views past events

etc.,

as noncontinuous,_ and the_imperfect_views

them

as continuous.

That is,

the preterit_ _is

used

to report events,

situations

etc.,

which

begin

or end--or both--at some time in the _past

which the speaker has in mind.

The imperfectp_on

the

other

hand,

is used

to _report

events,

situations

etc.,

which_neither begin_nor end_ at

the time the speaker is thinking of,

but

rather

which

have already begun and are in progress _or

existence

at this time...

Spanish

consistently

distinguishes

between

events in

progress and

events that begin and/or terminate,

by _choosing

the imperfect for the former and the preterit for

the latter.

English_may or may not

explicitly

make

the same distinction by_choosing particular

verb forms.

For example,

the expressions 'used

to' and 'was ---ing' clearly indicate habitual or

ongoing

events._

However, _in_all

other _cases

where Spanish

has_an imperfect, _English_has _a

simple

past tense_form

('had',_

'was', _'knew',

etc.) just as in all the cases. where Spanish

hat

the

preterit...

Another_ striking_ difference

between English

and

Spanish

is

that

English

sometimes

uses

completely

different

verbs tb

express distinctions that are_ made in_Spanish

by

choosing the

imperfect or

the

preterit.

_Fbr

example, the preterit of ocrocer is equivalent tb

'meet',

that is,

'begin an acquaintance', while

the

imperfect of

conocer

is

'know"be

_ _

acquainted with'.

Another_common_ verb that_ has

different English equivalents_in the preterit and

the imperfect is saber.

In the imperfect, saber

is 'know',

'have factual information',

while_ih

the

preterit

it is

'learn',

'helr',

'acquire

information'.

(Segreda & Harris, 1976, 105-106)

Thus,

it can be seen that students of Spanish must learn to

specify the context of past actions much more explicitly than

is

their

custom

in E:Iglish.

Generally, as Stockwell

and Bowen

(1965,

p. 284)

put

it,

the preterite/imperfect

demandrx

an

obligatory

choice in Spanish,

where there is often no choice in

English.

Indeed, it is for this reason that Stockwell and Bowen

place

this grammatical problem among those on the highest

level

of

their hierarchy of difficulty for English

speakers

learning

Spanish.

Empirical

evidence

of

the difficulty of

the

choice for

English speakers

is provided

by

Tran-Thi-Chau

(1975).

Restricting herself,

to a large extent, to Stockwell and Bowen's

work,

she

sought to determine the comparative difficulty of

33

different

Spanish

grammatical categories for English

speakers.

Her

findings,

based

upon the

responses

of 149

high-schooI

students

in Toronto,

enabled

her to set up

a hierarchy

of

difficulty of these 33 items.

Choice of imperfect/preterite was

the

second most difficult of the 33,

with an incorrect response

rate of

77%.

She

also assessed student

perceptions

of

the

diffictilty of the 33 items,

and found that choice of

imperfect/

preterite

was

considered the fourth most difficult category

by

her subjects.

In addition to the choice of imperfect/ preterite,

three

other categories

employed by Tran are

relevant

to the

present

study.

These

are Regular

Preterites, Irregular

Preterites,

and Regular Iffeerfects.

(It seems prof:P:131e that she

does

not list irregular imperfects because there are so

few of

them--only

three--in Spanish.

She does not explain her

reason

for this omission.)

It appears that under these categories

s e

listed errors made

in the form of the verb.

An

analysis of

students' errors and of their perceptions of relative

difficulty

revealed the following:

V. Wrong

O.D.

S.P.D.

Irreg.

Preteritet

44

23 17

Regul.

Preteritet

16

6

10

Regul.

Imperfects 53

26

21

Choice

of Tenses

77

32

30

0;D.=

Order of

difficulty of these itrims,

analysis of all 33 categories.

baSed uPon an

error-

S.P.D.= Student

Perception

of

difficulty of

these

items, in

regard

to

students'

opinions of

the

comparative

difficulty of all 33 categories.

Both

0.1)

and S.P.D.

figures rerresent positions on

a

scale from

1 to 33,

from

least

difficult to

most

difficult. Thus,

for instance, regular preterite forms

were

the

sixth least common

source of

errors,

while

choice of imperfect/preterite was the second most common.

Tran's

research did not specifically isolate the imperfect/

preterite as an object of study,

and,

as may already have

been

noticed,

the reader of her work must make guesses as to what her

figures actually represent.

Moreover,

the figure she cites for

regular

imperfects

(537. of

her

sample were

wrong on

this

category) seems extraordinarily high.

But it will be worthwhile

to

bear Tran's findings in mind in connection with the study now

to be described.

6

Spanish II Midterm at Pitt

The students whose performance is studied here were students

of

Spanish

2 at the Uriversity of Pittsburgh.

These

students

were

half-way through their second semester of Spanish at

Pitt.

They

had only

begun

their study

of

the preterite/imperfect

distinction

in the weeks immediately prior to

the

examination.

At the time of this study,

the Spanish II midterm examination at

the University

of Pittsburgh consisted of nine

sections.

The

exam

was not

strictly

timed, and

all

students

had th0

opportunity to finish.

rne section on the examination explicitly

tested

command of the preterite

and imperfect

tenses.

This

section

was composed of a prose passage in which the verbs

were

listed in their infinitive form.

The student's only task was to

write

in the

correct form of the verb,

obeying

the specific

instruction

that either the preterite or imperfect be

used.

A

copy of this section may be found at the end of this report.

85

students took the examination.

There

are

17 verbs to be conjugated in this

passage.

Of

these, nine need to be rendered in Spanish in the preterite while'

seven must be in the imperfect.

One verb,

Roder, was Judged to

be

contextually appropriate in either tense.

While there is

a

difference

in meaning carried by the choice of tense

;,:or Roder

here,

native speakers

deemed either

preterite

or imperfect

acceptable

in the context.

Four verbs;

levantarue,

vestkrse,

sentarse,

and Ronerse,

require a reflexive pronoun in

Spanish.

For

the purposos of this investigation, control of the reflexive

was considered irrelevant to the central question at issue.

7

Analysis of Errors

The total number of errors (T) was analyzed as +allows:

F:

Corr-ant tense choseni but written with an error in Form

Ns

Incorrect Tense chosen, but correct in form of that tense

Us

Blank entrieso

or forms which could not be assigned to

any

other category

Bs Entries

for which it was clear that the subject had

chosen

both

the

wrong tunse (imperfect/preterite)

and the

wrong

form of that tense;

The

responses:

following

tables

provide

a break-down

of student

Table 1

Total

No. of Entries

= 1445

(17 x 85)

Total

No. of Tense Choices

=

1360

(16 x 85)

Total

of optional choices

=

85

( 1 x

85)

Total

requiring preterite

=

765

(

9 x 85)

Total

requiring imperfect

=

595

( 7 x 85)

Total Errors on Entriec requiring Preterite

Ttital Errors on Entries requiring Imperfect

TOtal Errors

Table 2

S.rrors:

Preterite

Needed

Ti

284

Fi

134

(47%)

Ni

90

(32%)

Ui

51

(1R%)

B: 9

(3%)

= 284 (37%)

= 147

(24%)

=

431

(31%)

Imperfect

Total

Needed

147

12 (8%)

e4

(57%)

38

(26%)

13 (9%)

431

146

(34%)

174

(40%)

89

(21%)

22 (5%)

7

8

When

a particular entry is listed under U

above,

it is an

admitsion

that the

student was

trying

investigator was unable to

judge what the

to do.

So entries assigned to

category

U

comprised a variety of

most

common entries

inappropriate tenses,

these

cases,

it was

types.

Apart from spaces left blank% the

to be listed as U were

forms

of utterly

.g. present indicative or subjunctive.

In

impoasible to decide what the student

was

attempting ln

relation to the task

entey

is listed aS F above,

student was aware

the exact form of

under

B

above,

he had been

set.

When

an

a judgement had been made that

the

of which tense he had to use'

but did not know

the verb in this case.

Wheh an entrY i4 listed

it

has been judged tO be

attempt at

the

inappropriate tense of the two,

which was also

wrong in the form

of the verb in that inappropriate tense.

When an entry is listed

under N above,

it is clearly the correct form of the verb, in an

inappropriate tense.

It

might be suspected that a taxonomy such as this is

very

inaccurate,

since the only evidence we have for what the student

was

trying

to do is the word he wrote down on

the

examination

paper.

Since the tense is only recognizable morphologically, how

can we

assign

an entry to a tense when it

is

morphologically

incorrect?

In other words, the only way we

know that a student

chose

the

correct

tense is if he gave

the

correct

formx

an

incorrect

form, cannot be assigned with total confidence

to

any

tense.

8

While

this anomaly was taken into account,

the conduct

the

investigation showed that it did not pose any great problem.

Morphologically, Spanish preterite and imperfect verb-endings are

quite dissimilar,

and this distinction is reinfo.-ced by the fact

that

irregular

verbs tend

to

undergo stem

changes in

the

preterite.

Thus, the first criterion for assigning an entry to a

particular

tense

was

the

inflection

which

the

student

had

performed on it to mark the tense.

These inflections are op

ko

for preterite,

and aba,

ia for imperfect

The second criterion

was the stem irregularities of the preterite forms of many

verbs

in the

passage.

Where these criteria conflictede.g.

where

there was a verb-endins in the preterite added to a verb-stem

in

the

imperfect--the

ending was taken as the paramount

guide

in

judging

which

tense

was being

attempted.

In practice, the investigator, wno is an experienced teacher

of Spanish*

felt

that incorrect forms could be assigned

to

a

particular tense with a high degree of confidence;

Ths task was

really no more difficult that determining whether,

say,

*driyed

should

be taken as an attempt to form the present or the past in

English. Intuitively,

the

fact

that this

form

follows the

regular

past

paradigm outweighs the fact that its stem

is

the

stem for the present

most decisions in the present study were at

least as clear as this one.

10

General Findings

Of

the

grand total of verb entries with obligatory

choice

(1360)

only 431 were incorrect.

In other words,

most

entries

were correct in both choice ane form.

Next most common were the

entries

which

were wrong in only oue respect--either

tense

or

form.

Of the 431,

320 were wrong in only one respect.

Only 22

entries

were wrong in both choice of tense and form.

This is a

rather surprising figure.

Before the data were analyzed, it was

expected that lots of students would be wrong in choice of tense,

lots 04 students would write the wrong form of the verb, and lots

more would do both.

The results show that only the first two of

these hypotheses were borne out;

40% chose the wrong tense,

34%

the wrong form,

but only 5% did both.

This low value of B leads

to

the tentative conclusion that what we are dealing

with

here

are

two separate

processes;

choxce of tense for

a verb

and

knowledge of the correci: form of that verb in that tense are to a

great degree independent of each other.

40%

of errors were due to wrong choice of tense,

while 347.

were due to wrong forms of the right tense.

This suggests

that

choice

of tense

is marginally more difficult for

learners of

Spanish preterite/imperfect than are forms of those tenses.

The

greater

difficulty of choice of tense may be

underestimated

by

thene

data.

The

passage used in the examination was

to

some

extent

seeded with irregular verbs.

Thus the value of F may be

to some degree higher here than it would be for the language as a

whole,

thus causing the margin of F over N to be greater than is

revealed here.

10

11

Indkvi-dual Verbs

A discussion of the data en masse is of limited utility.

We

can come

to a

much better

understanding

of

learner's

'transitional

competence

(Richards 1974)

if we

examine

responses for each verb discretely.

For this reason,

responses

for each particular verb were analyzed,

and the most interesting

findings

are given below.

Verbs are listed here as regular

or

irregular;

this

applies to regularity in the tense required

in

the

context of the passage,

not to perfect regularity

in

all

passible

tenses of Spanish.

It should be remembered that

1=85

for all 17 of

1

1. levanto

these verbs.

Regu/ar Preterite

F= 2

N= 7

There is no striking pattern here.

As might

be

Li=

6

expected, the form of thit regular preterite did

13= 1

not

cause

much

difficulty.

Four of

unrecognizable

entries were in the present

the

tense

2. haci-a

forms.

Regular Imperfect

F= 1

The value of U is very

high,

COn5titUtin0 the

14=

1

highest proportion fOr U 'Lb be found f or any verb.

U=11

Analysis of entries classified Under U ShoWed

no

B= 0

clear patternr but most appeared to be composed by

analogy with irregular tenSet Of this verb (e.g.

Preseilt Indicative,

Future) or bY confusion

with

fortat of another verb, haber.

12

11

3. estaba

Regular Imperfect

F= I As expected,

a very Iow value for F

A rather

N= 3

high proportion of the total- errors were of

type

U= 6

U,

but these did not fall into any pattern.

The

B= 2

very Iow value of F is typical of those found

on

the

imperfects in this study.

These cast

great

doubt

on the reliability of Tran's rate of

error

(53%) for regular imperfects.

4.

vistio

Irregular Preterite

F=43 This verb is one of a small group of Spanish verbs

N= 1

whose stem-voweI is raised in the preterite. 30

U= 4 of

the incorrect forms were modelled

on the

El= 1

infinitive stem vestir, making its preterite form

regular *vestig.

Other common errors of form (4

of each) were *vest( and *visto.

The former is the correct first

person

preterite,

while the latter seems to stem from a

belief

that the verb is of the -ar conjugation,

for which the preterite

ending is -o.

Visto is also the perfect participle of

another

verb

ver (to see) and it is conceivable that this also

produces

interference.

In any case, vistig was the verb which occasioned

the most incorrect forms, leading to the suggestion that a slight

irregularity

(i for e) is trickier than a

gross irregularity.

Noteworthy also for this verb was the very low value for N.

12 13

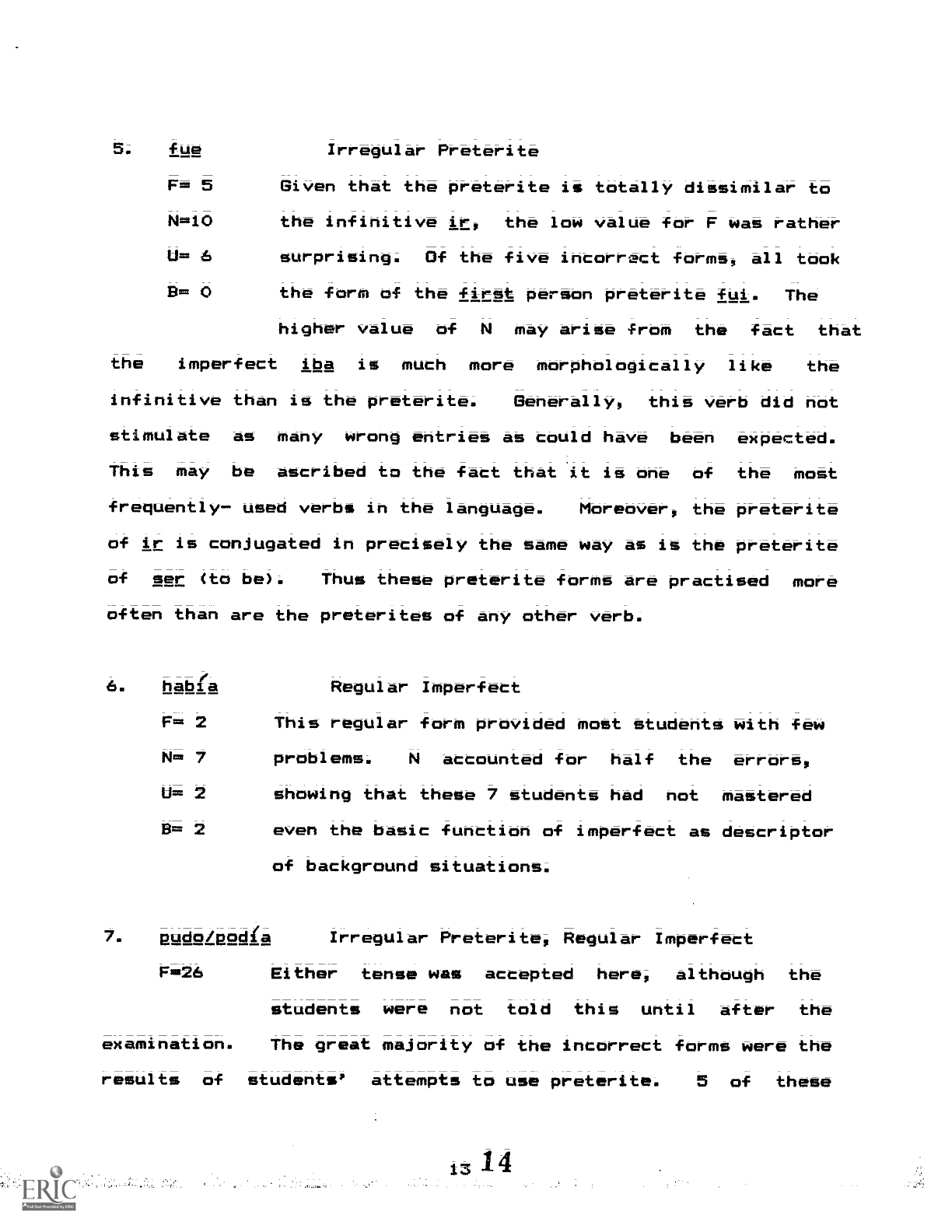

fue

F= 5

N=10

Irregular Preterite

Given that the preterite is totally dissimilar to

the infinitive ir,

the low value for F was rather

U= 6

surprising.

Of the five incorrect formt, all took

El= 0

the form of the first person preterite fui.

The

higher value

of

N

may arise from

the

fect

that

the

imperfect

iba is

much

more

morphologically

like

the

infinitive than is the preterite.

Generally,

this verb did not

stimulate as

many

wrong entries as could have

been

expected.

This

may

be

ascribed to the fact that it is one

of

the matt

frequently- used verbs in the language.

Moreover, the preterite

of ir is conjugated in precisely the same way as is the preterite

of

ser (to be).

Thus these preterite forms are practised

more

often than are the preterites of any other verb.

6.

habia

F= 2

N= 7

U= 2

El= 2

Regular Imperfect

This regular form provided most students with few

problems.

N

accounted for

half

the

errort,

showing that these 7 students had

not

mastered

even the basic function of imperfect as descriptor

of background situations.

7.

Rad° Ro

Irregular Preterite, Regular Imperfect

F=26

Either tense was

accepted here,

although the

students

were

not told this

until

after the

examination.

The great majority of the incorrect forms were the

results

of

students'

attempts to use preterite.

5 of these

1314

,

showed

*audiothe student

knew that

the verb was of the

irregular

group whose stem-vowels are raised in

the preterite,

but

he didn't

know that

moder is

doubly

irregular in the

preterite, since it takes the ending o (unstressed) which is mcr-e

like the o (stressed) of -ar verbs.

There were four first person

preterite pude,

and four first person preterite of another

verb

moner.

The

total number of errors (F=26) represents 31% of the

85 attempts.

This is striking in its equivalence to the rate of

errors of all types (31%) for the examination as a whole.

8. salio

Regular Preterite

F= 6

Only

six entries gave the wrong

form of

this

N= 6 regular verb.

Of these,

four used

the

first

U 3

person preterite sali.

B= 0

9. esaeraba

F= 1

N=25

Regular Imperfect

By far the greatest source of

error here was

choice of tense.

The context here clearly demands

U= 5

the imperfect, so it is regrettable that we have no

B= 2

way

of ascertaining why 25 students

chose

the

preterite.

Possible sources of error include the

fact

that a literal translation of the Spanish to English

would

result

in a rather strange phrase in English--"he expected it in

the be,x"--and,

in addition,

that the word buzon

was probably

unknoWn to the majority of the students.

14 15

10, delatla

Regular Imperfect

F= 3

A similar pattern of errors to the previous verb,

N=17

though not as striking.

Again,

it it

difficult

U= 4

B= 1

11.

sento

to see why 17 students chose the preterite.

It is

unlikely that the high rates of errors in

choice

of tense for

verbs 9 and 10

would have been

predicted by a contrastive analysis.

Regular Peeteeit

F=35 Why

did so many students give the wrong form

of

N= 6

this regular verb?

Analysis

of errors Shows

U= 5

two main types.

17 students wrote

*stentop they

B= 1

knew that the dipthongization of stressed

0 is

widespread

in Spanish,

but they

overgeneralized

this to embrace the unstressed e of the preterite.

The majority

of

the

remaining errors revealed confusion

with another

verb

sentir (to feel, regret).

This latter verb is of the type whose

stem-vowel is raised in the preterite,

and many of the incorrect

forms entered for sentar showed

for e in the stem.

12. leyg

F= 4

N= 3

U= 4

B= 0

Regular Preterite

As far

as the

subjects

of this study

were

concerned, this was the easiest verb on the entire

examination,

total errors

= 11. All

four

incorrect

forms exhibited

the firat

person

preterite lei.

13. interesaba(n)

Regular Imperfect

F= 2

N B

U= 5

Strictly, this verb should be written in the

plural, since the subject of the Spanish sentence

is incidentes.

However, it was decided to accept

13= 0

both singular and plural as correct, since the

students

had not yet practised

syntactical

patterns of

this

typei

Very few of

the entries,

(correct

or

incorrect) showed an attempt to

use the plural.

14.

Ruso

Irregular Preterite

F=16 The high proportion of unrecognizable

forms was

N= 3

due to apparent confusion with another verb Roderi

U=11

Of the 16 identifiable errors,

7 took the form of

13= 1

first person preterite.

The remaining 9

wrong-

form entries revealed 7 different kinds of errors.

15.

suRo

Irregular Preterite

F 10

The subjects had to make a fairly sophisticated

N=40

choice here.

The context of the passage demanded

U= 5 that

the preterite

(found out,

realized)

be

13= 2

employed rather than the imperfect (knew).

Nearly

hal; the students made the wrong decision on this

This

supports the contrastivists' expectation that the

greatest

difficulties

will arise when what is expressed lexically in

one

language

is expressed syntactically on anotheri

(It would be

very

interesting

to see how great this problem is

for Spanish

speakers learning English).

Of the ten errors in form, six were the

result of treating the verb as regular, and thus writing *sabio.

16 17

16. 1-1-ovia

Regular Imperfect

F= 2

It is very noticeable that such a high number of

N=23

students (23+5=28) chose to put this verb in the

U= 5

preterite.

This is despite the fact that this it

B= 5

one of the few verbs in the passage for Which the

English

equivalents closely parallel the Spanish.

Thus Spanish preterite would be rendered by English 'i-t

rAined',

while imperfect

would be translated as 'i-t

was ratning'. A

contre.stive

analysis would

be very unlikely

to predict that

students would choose the preterite to express 'it was

raining',

yet

this is

precisely what one-third of the students

in this

sample did.

17.

volvio

F=13

N=I2

U= 7

B= 3

Regular Preterite

Of the 13 incorrect forms,

the most common error

was to overgeneralize dipthongization of stressed

o to unstressed o.

Thus six students wrote

*vuelvio.

Discussion of Errors

The isolation

of individual verbs shows that the

finding

for the totality of the data--that N errors were marginaLly

more

common than

F errors--masks violent oscillations

in particlur

cases.

Thus for vistio,

for example, F=43, N=1, while for supo

F=101 N=40i

As might have been expected, F-type errors were most

numerous on irregular preterites, where the average for F was 12;

There

were very few errors of form on the imperfect

verbs; the

average

for each was F=1.7,

and in the case of three verbs F=1.

Of the three kinds of verb, the value of F for regular preterites

seems strangely high.

There is, on the surface, no reason why a

regular preterite should be so much more difficult than a regular

imperfect.

But this

high

value for F was accounted

for

by

examining all the incorrect responses, and it provided one of the

most

interesting findings of this study.

The data show

fairly

conclusively that it is not so much whether a verb is regular

or

irregular that counts, but rather whether a student suspects that

it may be irregular.

This suspicion is based on two factors:

1)

The

verb is of a stem-changing

type. Thewe may

be

viewed by students as "irregular" e.g.

sentar, volver.

2)

The verb

is confused

with other

verbs that

are

irregular, either in the preterite or in other tenses e.g. goder,

poner.

It should

be

stressed

that this similarity

is

morphological alone; there was no sign of any lexical or semantic

confusion.

Thus,

irregularites

in

the system of the target language

have a kind of spillover effect.

Awareness that some verbs

are

irregular causes other verbs to be treated as irregular;

just as

the regular paradigms are overgeneralized,

so also are irregular

inflections.

Errors

of this

type

must be

classified

as

intralingual, and seemed to result from a strategy of learning.

There

were a

number of traces

of pedagogically

induced

errors.

It

was

noticed that in many cases

the first

person

preterite

was given.

This trend could not be discerned in

the

18

19

case of the imperfect forms,

since first and third persons

are

identical

fn this tense;

indeed this is one of the reasons

why

the imperfect

forms

were so much easier

than the

preterite.

There

was also a certain amount of interference from the present

tense visible.

Both theme types of errors may result from

the

way the language is presented to the learner.

A large proportion

of

responses in drills arri free conversation in class will be in

the first person and/or the present tense.

These forms thus have

primacy

over

others.

Conclusion

This study was prompted by the desire to see whether English

speakers

luarning

Spanish

encountered

greater difficulty

in

choosing the appropriate imperfect/preterite tense or in learning

the correct forms of verbs in these tenses.

To u me ext:Pnt thit

distinction obeys the formula

interlingual/intralingual.

Verbs

describing

the past in Spanish are more marked--for aspect--than

is usually the z:ase in English.

Errors in the forms of

Spanish

verbs

are

a function of irregularities within

Spanish

itself.

While the

study' threw up a lot of interesting

information en

eassant,

no

firm

answer was obtained to the

central

question

investigated.

Tran's research mentioned earlier enabled her

to

categorize

interlingual

errors

as accounting for

51% of

the

total, with

intralingual

errors marking up 29%.

The present

study,

though not exhibiting such a great difference,

supportel

Tran

in

finding interlingual errors (40%) to be

somewhat

more

common than intralingual errors (34%).

Yet this cannot be taken

19

20

as a justification of procedures of contrastive analysis, for the

study revealed a significant number of cases where rate of

error

could

not have been

predicted on

the basis of similarity/

disSimilarity to English.

Appendixs Text Used in Examination

2122

SPANISH 2, KIDTERM EXNM

III.

InstruCtions:

Write in the appropriate forms

of the verbs in parentheses

to render the following

sentences into a correct

paragraph in_Spanish._ Use

the blanks to the tight.

Uge oniz past tense (preterite

and iriperfzet).

Juan (1-1evaterSe)

a las seis.

1.

;2-HacEr) frio y el cielo

(3-estar)

2;

3.

cubierto de nubes.

(4-Vestirse ) y

4.

(5-it) A IA cricina.

Como no

5.

(6-haber) ni Pan ni huevosi

no

6.

(7=podet) preparar el dzsayuno.

7.

(8--,Salir) a buscar el

petiodico,

lo (9-esperar)

en el ht0.6n dOnde

S.

9;

siempre lo (I0-dejar) el

mUchacho.

10.

(11=Sentatse) y (12-leer) el

11;

peri6dico desde el ptiacipio

haste

el final, con elweptiCA

de la Cecil-lice

social.

Nunca le (13=inteteSar) Ica

13.

incidenteg de la Vida SOCial.

Luego

14.

(14-ponetse) la chaqueta.

(15-Saber)

15.

que (16=116Ver) y (17-volver).para

16.

AI paragua

.

17.

.69.0646;

Ant,Jr.

References

Bulil William.

1965.

Spanish

or teacherszapplied linguistics.

New York; John Wiley.

Richards,

lack C.

1974.

Error analysis;perspectives an second

languase acquisition.

London]Longman.

Segreda,

Gui.lermc, anl James Ha..-rs.

1976.

Spardsha Listening

Speaking Readins Writing.

New Yorkp Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Stockwell,

R.P,_ and

J.D.

Bowen.

1965.

The

grammatical

structures of

English

nd

panish.

Chicago;

University of

Chicago Press.

Tran-Thi-Chau.

1975.

Error analyttis, contrastive analysis, and

students'

percepticni

a study of difficulty in second

language

learning. IRAL,

13, 2, 119-44.

2 4

22