The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S.

Department of Justice and prepared the following final report:

Document Title: Building a Comprehensive White-Collar

Violations Data System, Final Technical Report

Author(s): Sally S. Simpson, Peter Cleary Yeager

Document No.: 248667

Date Received: March 2015

Award Number: 2012-R2-CX-K016

This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally

funded grant report available electronically.

Opinions or points of view expressed are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the official position or policies of the U.S.

Department of Justice.

P a g e | 1

Final Technical Report

1

Building a Comprehensive White-Collar Violations Data System

Sally S. Simpson and Peter Cleary Yeager

1

Report submitted to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Grant No. 2012-R2-CX-K016

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 2

Contents

Abstract…..…………………………………………………………………..….....3

I. Overview of the White-Collar Crime Data Series…………………………..5

II. Conceptualizing the Series………………………...……………………….10

III. Prior Efforts to Measure White-Collar Offenses……..………………….....19

IV. Design Elements for Anticipated Data Series.…………………………......45

V. Assessing Available Data..………………………………………………....70

VI. Criminal and Civil Case Data: Strengths and Weaknesses………………...99

VII. Lessons learned from the Agency Briefs………….……………………...109

VIII. Conclusions and Recommendations………………….…………………..112

Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..121

Statutes Cited………………………………………………………………….…125

Appendix: Agency Briefs……………………………………………………….127

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 3

ABSTRACT

Despite its voluminous collections of data on conventional crimes and the legal responses

to them, the Nation has long lacked systematic data on white-collar offenses and the sanctions

employed against them. Because this void hampers research on and policy development for such

offenses, scholars and political leaders have advocated the development of an ongoing data

system that would systematically capture, measure, and describe these violations and the legal

responses to them. The federal Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), as the country’s leading

repository for the collection, analysis and dissemination of data on crime and justice processing,

is uniquely situated to develop a data series on white collar offenses. This BJS-funded project

proposes a design for such a series at the federal level and assesses opportunities and challenges

in its implementation.

The design elements for the data system include a definition of white-collar offenses that

distinguishes them clearly from other forms of offending and that corresponds to both

professional and popular conceptions of such violations. To achieve these goals we use a role-

centered definition that locates the motivations and opportunities for violations in legitimate

occupational and organizational roles. The data system comprises all violations of federal

laws—those sanctioned by regulatory/administrative, civil or criminal procedures—to represent

accurately the array of offenses and sanctions employed against them. From the federal agencies

and departments that enforce laws against white-collar offenses, it would systematically and

regularly collect enforcement case data on key factors: sources of identification of cases of

offenses, characteristics of offenses and offenders, and case outcomes.

Project staff assessed enforcement data characteristics, quality and availability in two

ways: through meetings and interviews with enforcement and data management personnel from

selected departments and agencies, and through examination of criminal and civil data held by

BJS as well as data made publicly available on a sample of agency web sites. Among the

findings and conclusions from these approaches are that (1) currently available data held by the

federal government’s enforcement units could contribute valuably to the formation of a data

series, but the data vary in terms of completeness and ease of accessibility across agencies;

(2) some agency personnel see the effort to build the data system as valuable to their own efforts

to improve the quality of their enforcement data; (3) the two agencies from which the project

sought agreements to share data with BJS to initiate the series both demonstrated early reluctance

to share the data; (4) agency web sites with publicly available enforcement data are a promising

source of information for the data series; (5) with current data sources we are commonly not able

to identify individuals who offend in legitimate occupations because role often cannot be

determined unless persons are listed as co-defendants with organizations; even then

distinguishing white-collar civil and criminal cases (as defined herein) from conventional

offenses can be uncertain because the available data do not clearly differentiate between

legitimate and illegitimate organizations; (6) demonstration projects between Department of

Justice enforcement divisions and agencies that share jurisdiction with them have promise for

both assessing data quality and completeness and promoting ongoing data-sharing for the white-

collar offenses data system; (7) BJS should continue its efforts to develop the data system.

Among other steps it should seek to form an ongoing working group that includes relevant

personnel from key enforcement units and agencies to share information on enforcement data

management challenges, needs and goals, to discuss the purposes and goals of a white-collar

offenses data system, and to discover the synergies between the enforcement units’ efforts to

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 4

improve their own data systems and the ongoing development of the new BJS data system for

white-collar offenses.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 5

I. Overview of the White-Collar Crime Data Series

A. Framing the Issue

Since its inception the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) has collected,

analyzed, published, and disseminated information on crime, criminal offenders,

victims of crime, and the operation of justice systems at all levels of government.

A notable exception to this comprehensive coverage is the lack of information

about white-collar offenses, offenders, and justice system responses, even though

the collection of such data was one of the original tasks outlined for the agency.

2

Although the United States has long had annual accounting systems for

conventional crimes (including data collected and held by BJS) that have

underwritten countless research investigations and informed public policy

deliberations, the data landscape for white-collar offending is significantly more

constrained. There is no systematic accounting of white-collar offenses and

available data are substantially limited in scope and content. BJS does hold some

case and defendant-level criminal and civil enforcement data

3

on “white-collar”

crime from which it has issued select reports on Federal Enforcement of

Environmental Laws (Scalia, 1999) and white-collar offending at the state- and

federal-level (BJS, 1986; Mason, 1987), but the information is not organized in

2

BJS was created under the Justice Systems Improvement Act of 1979 to “promote the collection and analysis of

statistical information concerning crime, juvenile delinquency, and civil disputes.” It was mandated, among other

tasks, to collect “information concerning criminal victimization, crimes against the elderly, and white-collar crime”

(emphasis added).

3

The civil data have not been explored or used to the same extent as the criminal case processing data.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 6

such a way that enforcement actions against individual or organizational

defendants can be followed over time or linked across criminal, civil, and

regulatory justice systems. Indeed, regulatory enforcement data on organizations

are for the most part absent, and details about offenders and victims are sparse.

Consequently, it is impossible to track the extent of known white-collar violations

in the United States over time, to describe the characteristics of cases and

defendants, or to capture the full array of sanctions levied in a particular case or

against perpetrators.

The inability of the federal government consistently and accurately to report

known instances of white-collar offending has far-reaching consequences for

general knowledge, scientific investigation, and evidence-based policy in this

important area. “Policies are formed and legislation is passed, often seemingly

rationalized by little more than carefully selected anecdotes that seem to support a

particular policy when taken in isolation—and that can easily be countered by

other anecdotes that are supportive of an opposing point of view” (Dunworth and

Rogers, 1996: 499-500). Such an empirically deficient approach toward white-

collar crime virtually ensures “combativeness and policy mistakes”.

4

4

This policy-related observation was made by Dunworth and Rogers after their assessment of data on big business

litigation in Federal courts, but it is equally apt for white-collar crime.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 7

Confounding the development of a comprehensive data collection and

management system is the lack of conceptual clarity surrounding the definition of

white-collar crime. Because white-collar crime is not a legal category, definitions

abound. Criminologists and legal scholars have defined and classified white-collar

crime in a variety of ways. Some definitions focus on offenses committed by

companies and their managers to achieve the goals of the business, while others

emphasize offenses committed by individuals that may or may not involve

organizational or business resources but tend to be tied more to self-interest and

guile (e.g., embezzlement or tax fraud). Consistent with Sutherland (1949), social

scientists often prefer offender-based definitions of white-collar crime which call

attention to the social position of the actor. For Sutherland, white-collar crime was

“committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his

occupation” (1949: 9). The behaviors he had in mind were not necessarily (or

even typically) pursued, prosecuted, and punished in the criminal justice system.

Instead they were handled commonly through civil and administrative justice

processes. But they met the general criteria of criminal behavior, i.e., offenses

defined by the “legal definition of social injuries and (ultimately the) legal

provision of penal sanctions” (Sutherland, 1983: 52). Although Sutherland’s

definition emphasized individual-level characteristics, his empirical research

focused on the offenses of corporations—an inconsistency that caused definitional

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 8

confusion and the subsequent parsing of white-collar crime into criminal behavior

systems that helped to organize, classify, and make sense of the extensive range of

behaviors captured by Sutherland’s conceptual and empirical work (Clinard et al.,

1994).

In contrast, offense-based definitions of white-collar crime focus on the

means through which the offense is perpetrated and its characteristics, as in

Edelhertz’s (1970: 3) definition: “an illegal act or a series of illegal acts committed

by nonphysical means and by concealment or guile to obtain money or property, to

avoid the payment or loss of money or property, or to obtain personal or business

advantage”. Edelhertz recognized distinct types of white-collar offending within

this broad definition, including personal crimes (individuals who act by themselves

for personal gain in a non-business setting); abuses of trust (people operating

within legitimate businesses and other organizations or professions who violate

their duties to an employer or client); business crimes (crimes that further business

interests but are not the primary focus of the firm); and con games (illegal acts by

an illicit organization whose business is white-collar crime) (Edelhertz, 1970: 19-

20). This focus on the offense itself rather than the social position of the actor

emphasized the diverse and extensive nature of fraudulent behavior.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics originally incorporated both offender- and

offense-based approaches into a single definition of white-collar crime. The

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 9

second edition of the Dictionary of Criminal Justice Data Terminology (1981:

215), for instance, described white-collar crime as “nonviolent crime for financial

gain committed by means of deception by persons whose occupational status is

entrepreneurial, professional or semi-professional and utilizing their special

occupational skills and opportunities; also nonviolent crime for financial gain

utilizing deceptions and committed by anyone having special technical and

professional knowledge of business and government, irrespective of the person’s

occupation.” Practically, however, most criminal justice data management systems

do not collect information about the offender’s occupational status or special

knowledge utilized to commit the offense. This reality ultimately restricted the

operational definition of white-collar crime to “nonviolent crime for financial gain

committed by means of deception” (Mason, 1986: 2) and produced a classification

scheme in which forgery, counterfeiting, fraud, and embezzlement constituted

white-collar crime. Notably, the classification of white-collar crimes in this

manner was not driven not by conceptual considerations but rather by data

limitations.

B. Justification for the Series

Recognizing existing data deficiencies and the need for research and

development on the topic, BJS contracted with Professor Sally S. Simpson

(University of Maryland) and Professor Peter C. Yeager (Boston University) to

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 10

assess the feasibility of developing a statistical series that would integrate criminal

and civil data that BJS receives from the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys

(EOUSA) and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AOUSC) with

enforcement data from federal regulatory agencies. The ultimate goal of this effort

is to describe comprehensively the federal response to white-collar violations and

offer recommendations for series design and content. This Technical Report

summarizes the conceptual and methodological approach adopted by Simpson and

Yeager to map the data landscape. It also utilizes and assesses data from specific

agencies to demonstrate the feasibility of this approach.

II. Conceptualizing the Series

A. Principles and Aims

The conceptual basis for the data series comprises a number of key principles

and aims. A data series on white collar violations of federal laws should, of

course, meet the standards of reliability and validity. In practice these translate to

the requirements that the measurement schema being employed are

comprehensive, clear and replicable, and that what is being measured comports

with a concise, analytically-based and clear definition of the phenomenon of

interest.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 11

Because white collar offenses comprise a large and diverse array of illegal

behaviors, a data series for them must, in pursuit of comprehensiveness, be able to

integrate diverse existing databases into a single system of accounting. This

requires a coding system with two important characteristics that exist in a certain

tension with each other: that it be broad enough to capture the key points in the law

enforcement handling of cases of white collar offending, and that its data collection

categories be adequately concise to capture reliably and consistently these data

points from among the widely varying federal data systems in which the violations

and enforcement data originate.

Finally such a series should be maintained in timely fashion, and it must be

an ongoing endeavor with regularly scheduled additions of data on new cases—and

new developments in existing cases—to the database. And as a routine component

of the maintenance and growth of the series, there should be ongoing assessments

of data quality, of the series’ utility for both policy and research purposes, and of

potential improvements in collection and measurement. Such efforts will not only

ensure the quality of the data series, but should also have the effect of working

synergistically with parallel efforts of participating federal agencies to improve

their own data management processes toward the more uniform, effective and

useful measurement of white collar offenses and enforcement in the federal

government.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 12

The principal justification for and value of a data series on white collar

offenses are the contributions it will make to research and public policy. An

ongoing series of the sort envisioned here would not only provide unprecedented

opportunities for research on patterns of white collar law-breaking and the federal

response to it. Its availability would also promote such research in an area of

investigation that has been sharply limited by the lack of available data. To the

extent that the data series on white collar offenses permits and promotes this

research—much as the well-established National Crime Victimization Series and

the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports have long underwritten the voluminous research

on conventional crimes—to that extent will law enforcement, legislators and

judicial personnel have access to a body of knowledge that will contribute to

improved policies for addressing this form of offending.

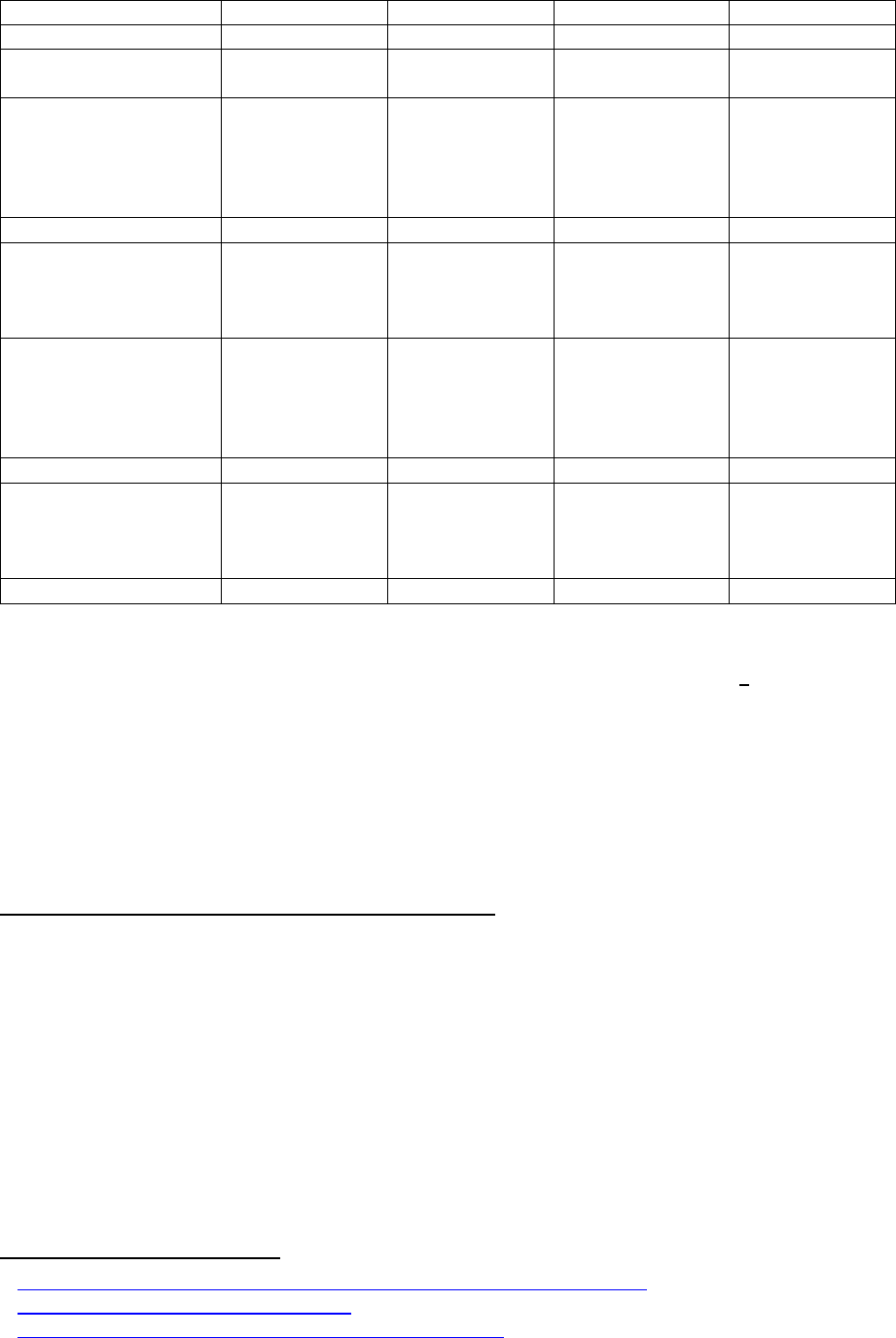

Key to a successful data series is an efficient and uniform system for data

collection and coding of information. This database system needs also to capture

information on the key factors or ‘moments’ in the handling of cases of white

collar offending. Figure 1 offers a simplified schematic presentation of those key

factors.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 13

The three primary types of information for inclusion in the series are the

sources of identification of cases of violation, data on offenses and offenders that

are processed for enforcement, and information on case outcomes, including

sanctions and referrals for further legal action. The latter is especially relevant for

cases originally processed and/or sanctioned by regulatory agencies that later refer

them to U.S. Justice Department attorneys for criminal prosecution. For each of

the three categories of data it is necessary to construct a parsimonious coding

system that permits and guides the translation of contributing enforcement

agencies’ diversely structured and variably inclusive data into reliable and

homogeneous indicators of the key variables. The development of an effective

‘crosswalk’ system for the purposes of this translation is essential to the

construction of the data series on white collar offenses.

Figure 1

Case

Source

•Complaints

•Referrals

•Investigations

Case

Processing

•Case Types

•Charges

•Defendants

Case

Resolution

•Violations

•Penalties

•Referrals

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 14

B. Methodological Matters

A white-collar crime data series should classify conceptually similar acts

using a sensible, commonly understood and culturally shared definition. Among

other reasons this is because such a series requires both legal and cultural

legitimacy—in an arena that is highly contested and often misunderstood. Because

U.S. laws hold that legal entities such as corporations are generally to be treated

under the law as persons, the series would encompass both offending individuals

and organizations (inclusive of for-profit, nonprofit and governmental actors). The

scope of the series would include all federal agencies’ criminal, civil, and

regulatory enforcement cases that are consistent with the definition. Although

there is broad variation in the types and quality of data available from regulatory,

civil and criminal law sources, the breadth of extracted data would capture key

offense, offender, and sanctions variables that are commonly defined, counted, and

measured across sources. The series should link initiated and processed cases of

offending across the distinct legal fields, and track respondents and defendants

(individually and co-offenders) across stages in the justice process over time. In

sum, it should maximize data comprehensiveness and compatibility and set a

strong foundation for future agency collaborators in the series.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 15

Challenges in Regulatory Data. On the face of it, the collection and

integration of regulatory data into a Federal White-Collar Crime Statistical Series

should be straightforward. Each regulatory agency was created by Congress

through enabling legislation that defines its purposes, tasks, and powers. Agencies

monitor actor compliance with specific statutes and regulations using a wide array

of mechanisms (e.g., inspections, self-reports). These agencies conduct

investigations, obtain reports from firms, keep records of investigative findings,

and hold hearings to establish violations of regulations and laws. Investigations

may result in case referral for criminal, civil judicial, and/or administrative

proceedings.

The reality, however, is much more complicated. Because agencies vary in

their specific tasks and powers, the data they collect and maintain also varies.

First, the quantity of data varies greatly between agencies. Some agencies

investigate and pursue hundreds of violations yearly while the capacity of others is

much smaller. Second, the mix of data also diverges by agency. A number of

regulatory agencies have broad authority to pursue civil litigation and criminal

investigations using their own investigators and attorneys, others do not. The

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), for instance, can pursue violations of

law as civil administrative cases, civil judicial cases, or criminal investigations

(EPA investigators have warrant and arrest authority, although on finding evidence

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 16

of criminal offenses it must refer the cases to Justice Department attorneys for

prosecution). Other agencies’ powers, however, are more restricted. Enforcement

activity by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), for instance, is limited to

administrative proceedings or the pursuit of civil actions in Federal court. Cases

thought to merit criminal charges are referred to the Department of Justice

Antitrust Division for investigation and prosecution.

5

Similarly, the Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC) has the authority to bring a civil case in federal court

or before an administrative law judge within the SEC. Criminal enforcement of

the Federal securities laws is pursued through the U.S. Department of Justice and

the individual U.S. Attorneys General throughout the country. Third, case data

held by specific agencies will not always be exclusive to a single agency because

cases stemming from the same incident for the same conduct may be brought

simultaneously in different venues. For example, a defendant in a criminal

securities fraud case brought by Justice Department prosecutors may also be

subject to civil justice processing by the SEC. Further, there is some evidence that

criminal actions by the government are more likely to be brought in cases

involving both environmental and employee safety laws.

6

In such situations the

5

Because the Department of Justice Antitrust Division and the FTC share statutory authority for certain sections of

the Clayton Act, and because the FTC can challenge conduct under the Sherman Act, the two agencies must

coordinate with one another to determine, as each case arises, which agency is most appropriate for handling the

matter.

6

See, e.g., http://www.oshalawupdate.com/2012/12/18/osha-criminal-referrals-on-the-rise/.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 17

two agencies’ case data will overlap to the extent that they report on the

investigations that led to referrals to the Justice Department for criminal

prosecution.

This “duplication” of cases is complicated by whether individuals and

organizations within a case share similar or distinct sanction processes. So, for

example, a case of securities fraud may name five defendants in a civil case—two

organizations and three individuals—but parallel criminal charges may be brought

only against the organizations and not the individuals. Given that one of the key

goals of the white-collar crime statistical series is to track case-specific sanctions

against defendants across justice processes, this nettlesome problem must be

resolved.

Challenges in Criminal and Civil Data. Federal criminal and civil data

sources, available from the Executive Office of the U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA) and

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AOUSC), must be merged with the

regulatory agency data in order to describe comprehensively the federal response

to white-collar violations.

7

The EOUSA data track criminal and civil cases and

defendants from matters presented to and/or pursued by the U.S. Attorneys, while

the AOUSC data contain civil and criminal case and defendant court filings and

7

Both EOUSA and AOUSA data are extracts from the case management systems used by federal prosecutors and

federal courts, respectively, for their specific administrative purposes. Therefore, the type of information we might

require for the data series on white-collar offenses may not always be available or accessible.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 18

outcomes in the U.S. Courts. Both data sources contain fairly detailed case

descriptions. However, there are notable insufficiencies in these data. Although

we will provide more details later in this report, several key differences in what is

recorded (and required to be reported) and how cases are counted between these

sources impact data comparability, completeness, and reliability.

On the criminal side of things, the EOUSA data include a variable for

referring agency and a flag (drawn from the variable participant type) to highlight

whether the case-defendant is an organization (which includes collective groups of

all types). The AOUSC data lack this flag and do not report referring agency.

Neither source offers much detail about organizational defendants, nor is the flag a

required data element. AOUSC data provide more detail on the violations charged

in a case (up to five unique charges) but the EOUSA reports only the lead charge

(and do not contain the statute violated for Matters Referred for Prosecution).

For civil court cases both data sources are less useful for our purposes. For

instance, the AOUSC civil data lack referring agency, a participant type flag, and

plaintiff/defendant information; it also is not possible to disaggregate defendants in

the same case. In addition, the data make it impossible to distinguish regulatory

agency action from DOJ action, from third party action, and so on. Because the

unit of analysis in the EOUSA data is case-defendant and the data currently lack

case or docket numbers, it is not possible to link defendants within the same case, a

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 19

connection that the criminal case data allow. Both data sources report one statute

associated with the case, but it is unclear if the case type variable

8

is the same

across the two datasets.

From this brief review, it is clear that the design and structure of a

comprehensive white-collar crime data series will be challenged by the strengths

and weaknesses of the kinds of data available to build the series. To better

understand what this means for our current efforts, in the next section we

summarize and assess how others have approached this problem.

III. Prior Efforts to Measure White Collar Offenses

This project is far from the first attempt to conceptualize and measure white

collar violations in a systematic manner. Although we have drawn and built upon

these earlier efforts, we have not adopted full-scale any approach as each has its

strengths and limitations. Most notably, there are differences in the focus and

scope of white-collar crime across studies that, in turn, affect the source and kind

of data utilized (Johnson and Leo, 1993). It is also important to keep in mind that

the empirical studies were designed to answer specific research questions and not

to build a data series. Below, we briefly summarize these efforts and highlight the

8

The AOUSC and EOUSA data include offense categorizations (such as “environmental offenses” and “antitrust”)

but it is unclear if these categories encompass the same statutes across the two databases. If it were possible to

verify which statutes are included in these categories, and confirm that they are consistent across databases, they

would be useful for efficiently identifying particular offenses of interest, without having to search for specific titles

and sections of statutes.)

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 20

key elements that have informed our project, beginning with the seminal work of

Edwin Sutherland.

A. Research-Based Efforts: Goals and Purposes

Edwin Sutherland. Although his definition of white-collar crime focused

on individuals, giving rise to offender-based approaches (“crime committed by a

person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation,”

1983: 11), Sutherland’s empirical research focused on companies. Sutherland

provides no rationale for this disconnect but it is possible that it was more

expedient at the time to sample, identify, and track firms as compared to

individuals. Moreover, the fact that crimes by business attack the fundamental

principles of American institutions—a key element of white-collar crime for

Sutherland—is also a strong justification for the company focus. To quote

Sutherland (1983:13), “white collar crimes violate trust and therefore create

distrust; this lowers social morale and produces social disorganization. …Ordinary

crimes, on the other hand, produce little effect on social institutions or social

organization.”

Sutherland studied the life history of 70 of the largest publicly- and

privately-owned corporations in the United States with regard to their violations of

law. Specifically, he used case and offense data reported by federal agencies and

the New York Times to examine restraint of trade, misrepresentation in

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 21

advertising, unfair labor practices, financial fraud and violation of trust, violations

of war regulations, and a small number of miscellaneous offenses.

9

To measure

legal violations, Sutherland employed formal decisions and orders of the court and

administrative agencies against a firm, including stipulations accepted by the court

or agency, settlements ordered or approved by the court, confiscation of food (in

violation of the Pure Food Act), and a few other ex post facto cases that had been

dismissed earlier. Sutherland thus relied on cases prosecuted, litigated, and

brought in regulatory/administrative, criminal, and civil justice venues. This

approach allowed him to then examine offending patterns over time, within firms,

across industries, and by legal venue.

Sutherland’s unit of count is a decision within a case. His rules for counting

decisions were as follows: (1) when three companies are defendants in a law suit in

which a decision is made, the decision is counted three times—once for each firm.

(2) If parallel cases are brought in different legal venues and found against one

company for essentially the same overt behavior, two decisions are counted. (3)

One decision may summarize multiple charges and behaviors that have taken place

over many years (e.g., price-fixing). In effect, all the charges and years are rolled

9

Sutherland did not specifically sample firms on any basis other than size (68 of the companies were listed on two

lists of the 200 largest non-financial corporations in the United States) and specialization—excluding corporations in

one industry and public utility corporations—although he did examine 15 of the largest power and light corporations

for comparison purposes.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 22

into a decision with a corresponding count of one (1983: 19). Depending on the

rule, Sutherland’s methods may increase the potential for over-counting or

undercounting offenses.

The key elements of Sutherland’s approach are as follows: (1) The decision

to track offending by legitimate businesses; (2) offending is captured across

criminal, regulatory, and civil venues (including private suits); (3) offense types

are constrained to five broad categories of crimes and some miscellaneous

violations; (4) an offense occurs only when a decision is determined against the

firm; (5) time is censored by the life history of the firm and the conclusion of the

study (1949).

Yale Studies. A very different approach was adopted by Stanton Wheeler

and his collaborators at Yale University (Wheeler et al., 1988; Weisburd et al.,

1991; Weisburd and Waring, 2001).

10

These researchers studied individual

offenders in seven federal courts between 1976 and 1978 who were prosecuted for

and found guilty of violating one (or more) of eight offenses in the federal criminal

code. This approach is consistent with a statute-based strategy for counting and

measuring white-collar crime and an offense-based definition of white-collar

crime. Wheeler and his colleagues (1982: 642) define white collar crimes as

10

A number of other researchers were involved in these efforts, but our concern here is how white collar offenders

and offenses were defined and measured in the Yale studies. Thus, we cite the works most relevant for our

purposes.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 23

“economic offenses committed through the use of some combination of fraud,

deception, or collusion.” The specific offenses selected for study included

securities violations, antitrust violations, bribery, bank embezzlement, mail and

wire fraud, tax fraud, false claims and statements, and credit- and lending-

institution fraud.

Once all offenders who met the inclusion criteria were identified, the

researchers then stratified and sampled among the offenders. Because there were

so few securities fraud and antitrust offenders,

11

all of these offenders were

selected for the study, whereas a random sample of the other offenders was drawn.

With sample in hand, the study then focused on the characteristics of the offenders

AND the offense committed. Offender and offense information in the study came

primarily from Pre-Sentence Investigative reports—documents prepared by the

probation officer, often with input from law enforcement and prosecutors—that

judges can use to inform sentencing decisions.

The Wheeler et al. (1988) approach to counting and measuring white-collar

crime has several key features, including the decision to focus on: (1) criminal

offenses; (2) individuals and not organizational offenders, although the researchers

track whether a corporate indictment was issued in the case; (3) a limited number

11

The fact that so few of these cases are criminally prosecuted says something about the limitations of the criminal

data source.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 24

of specific offenses (eight) and federal courts (seven) from which to select

offenders; (4) the sentencing stage of the criminal justice process (i.e., guilt had

been determined); and (4) a constrained set of years (1976-78)

12

. In addition, the

study depends completely on the availability of PSI reports to link relevant

offender and case information.

Wisconsin Study. The NIJ-funded research project on corporate crime

(Clinard et al., 1979; Clinard and Yeager, 1980; 2006) has more in common with

Sutherland’s approach to white-collar crime than it has with Wheeler’s. In the

Wisconsin study, the researchers focused on legitimate corporate actors and

tracked offending across administrative, civil, and criminal justice venues—actions

taken by a total of 25 federal agencies (Clinard and Yeager, 2006:110). Unlike

Sutherland, however, the Wisconsin study adopted a definition of crime that was

consistent with the subject of their research. Corporate crime was defined as “any

act committed by corporations that is punished by the state, regardless of whether

it is punished under administrative, civil, or criminal law” (Clinard and Yeager,

1980:16). Corporate crime is a subtype of white-collar crime that has distinct

features in that it is organizational in nature and occurs in the context of complex

corporate relationships.

12

Weisburd and Waring (2001) extended this time period by collecting official measures of criminality (arrests)

from FBI rap sheets for the original sample through 1990.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 25

The Wisconsin study’s sample of companies was substantially larger than

Sutherland’s (477 of the largest publically-owned U.S. manufacturing companies,

plus an additional 105 public companies in the wholesale, retail, and service

industries), but the increase in the sample size negatively affected the length of

time firms could reasonably be followed (1975-1976).

The Wisconsin project operationalized crime more broadly than did either

Sutherland or the Yale studies. Researchers gathered information at a point earlier

in the justice process and included all known initiated cases and enforcement

actions taken against a corporation. This technique is comparable to studies of

street crime that operationalize crime using police statistics (crimes known to

police). While the previous studies can be criticized for ignoring the winnowing or

funneling process whereby cases are diverted out of the legal system (if brought at

all), the Wisconsin study can be criticized for including actions that companies

may not, in fact, have committed or for which they are not legally responsible.

The range of violations covered in the Wisconsin study was far broader than

that covered by Sutherland, but there was overlap as well. The specific types of

violations included administrative, environmental, financial, labor, manufacturing,

and unfair trade practices (Clinard and Yeager, 2006: 113-116). An additional

special feature of the Wisconsin study was that researchers created a classification

scheme to rank violations as serious, moderate, or minor. The authors point out

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 26

that because most agencies did not have severity criteria (Clinard and Yeager,

2006: 118), their determinants of ranking were tied to things such as repetition of

the same offense by the company, intent, the spread of the crime within a

company, harm to victims (calculated in several different ways), firm refusal to

take pro-social actions (such as recall, reinstate or rehire employees, refusal to

honor agreements), threatening actions by the firm, and the length of time of the

violation.

A main goal of the study (1979) was to understand the etiology and patterns

of, as well as responses to, corporate crime. Therefore, in addition to capturing

initiated and enforcement actions against companies from a variety of different

sources, the study also utilized information about firm characteristics (such as

company size, financial performance, and market characteristics) to analyze the

relationship between these and firm offending records.

Yeager Study. Yeager’s (1987, 1991) research focused on the enforcement

of federal environmental laws against business polluters. It examined the social

and political factors that shaped both offending and enforcement decisions. While

its data base was a narrowly construed one—compliance and enforcement among

industrial violators of the federal Clean Water Act in New Jersey—its construction

illustrates some of the key matters that a data series on white collar offenses must

manage.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 27

For example, at the time of the research the Environmental Protection

Agency’s compliance and enforcement data systems varied significantly by

regulatory region in the U.S. Only Region II, which includes New York and New

Jersey, maintained longitudinal electronic records on polluting facilities.

Moreover, the two states varied in their enforcement authorities. In New Jersey,

the EPA itself monitored industrial compliance and enforced the law against

violators, while in New York State the Agency had delegated enforcement of the

Clean Water Act to the state’s environmental regulators, as allowed by the law.

Yeager’s analysis focused on the New Jersey data, which avoided the need to

ascertain any differences between the two states in data coding protocols and

enforcement priorities.

The unit of count for the study was the firm-violation, the goal being to

ascertain the number of violations of the law for each company over the period of

time during which its effluent had been regulated. Because the EPA data were

kept at the facility level, it was necessary to aggregate violation (and sanctions)

counts for facilities owned by the same company. This was possible because the

data included the name of the facility owner, but at times the aggregation required

careful matching of names as some facilities were owned by subsidiaries of major

corporations.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 28

Because of the way information was entered into the data base, it was also

necessary to construct analyses of offenses (counts) that normalized them across

facilities and firms. Many violations were reported on self-monitoring reports that

facilities were required to submit to EPA on schedules set for each facility, e.g.,

monthly or quarterly. Therefore, the number of offenses reported per year could in

part be an artifact of the number of reports required during the year, requiring

normalization of the counts.

Simpson Studies. Two separate white-collar (corporate) crime studies

conducted by Simpson (1985; 2007) also inform our strategic approach to the BJS

data series. The first study tracked the offending behavior of 52 “survivor”

companies over a 55-year time period (1927-1981) in the United States. The

companies were randomly selected from seven basic manufacturing industries.

The only criteria for selection were that they stayed in business for most if not all

of this time period (in some form), they continued to operate within the industry in

which they operated in 1927, and that the firms were US-based. The study focused

on only one type of illegal activity—alleged anti-competitive behavior—and used

two data sources to connect criminal, civil, and regulatory offending information

with companies. Cases were drawn from the Federal Trade Commission Case

Decisions and Trade Cases, which contain "texts of decisions rendered by federal

and state courts . . . involving antitrust, Federal Trade Commission, and other trade

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 29

regulation law problems" (Trade Cases, Introduction). Simpson also was

interested in corporate crime etiology and enforcement, so additional data were

drawn from sources such as Compustat, U.S. Census of Manufacturers, firm 10K

Reports, and the Statistical Abstract of the United States. These data were matched

with firm offending records to examine the economic and political context in

which offending occurred. To establish the proper temporal ordering between

economic characteristics and offending, cases were coded according to the year in

which the offense allegedly occurred (as per agency case documents), not when the

case was brought. Offense counts were created when a case was brought against a

company. Cases were tracked over time so that resolutions could also be

ascertained and classified by outcome (e.g., settlement, guilty finding, cease and

desist order). If a case was appealed, that was noted in the data. Simpson also

created a seriousness measure to rank the anti-competitive offenses. Offense type

was not utilized to ascertain seriousness because there were so many different

kinds of cases captured within the same offense type. Instead, two categories of

seriousness were created (serious and trivial) based on the degree of harm each act

engendered and victim class similarity (e.g., suppliers, customers, competitors).

Serious violations, such as all forms of price-fixing, predatory pricing, conspiracy

to monopolize and control territories, interlocks, and illegal mergers, were those in

which the cost of the act was high for another or potential competitor, resulting in a

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 30

substantially less competitive market. Most (but not all) cases of unfair advertising

and warranty violations were coded as trivial, i.e., those acts that, while widely

dispersed, have marginal economic effects on victims. A middle category of

seriousness (moderately serious) was created but not utilized due to the higher

potential for coding errors within this category.

The second Simpson study (Simpson, Garner, and Gibbs, 2007), funded by

the National Institute of Justice, used a triangulated research strategy that included

interviews with inspectors, secondary data analysis, and factorial surveys to assess

the deterrent effects of different kinds of state responses to firms that failed to

comply with environmental regulation, specifically the National Pollutant

Discharge Elimination System as authorized by the Clean Water Act. Therefore,

the study was designed to compare the effect of cooperative versus punitive

approaches on corporate recidivism. Only the construction of the secondary

analysis data set is relevant for our purposes here.

Simpson, Garner, and Gibbs (2007) randomly selected firms in four

manufacturing industries (pulp, paper, steel, and oil) in 1995. This strategy

produced a distribution of 30 pulp and paper companies (the two industries were

combined because of substantial overlap in the firms and facilities in the two

industries), 18 steel companies, and 19 oil companies (N=67). The companies

were followed through the end of 2000 by which time, due mostly to mergers, the

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 31

total number of firms was reduced to 55. The study relied on information collected

by the EPA in their Performance Compliance System (PCS) database and docket

files (administrative, civil, and criminal case files) to measure company violations.

Enforcement data in both data files (PCS and EPA dockets) were likely to overlap

to some degree, but there was no method for tracking the same violation by the

same offender across data sources.

The violation data (pollution and compliance schedule violations, as well as

EPA enforcement activity) are captured at the facility level, but because the focus

of the study was on the firm and not the facility, facility violations were counted,

aggregated and matched to the specific companies in the sample. If a company

owned several facilities, the firm offending count was a sum of the violations

counted at each of its facilities. Annual aggregation (normalization of count) was

also necessary as some compliance schedule requirements are monthly or

quarterly. A unique feature of this study is that it captured both inspection data and

“self-report” data—information that allowed researchers to create measures of

opportunity and to construct rate variables (number of violations/number of reports

required).

The EPA study also collected economic and structural information about the

firms in the sample that allowed the researchers to address two additional research

questions: (1) Are certain characteristics of companies associated with a greater

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 32

offending risk? (2) Do firm characteristics affect the type of intervention and

punishment a company receives when a violation occurs?

Schlegel SEC study. Another study of white-collar crime, funded by the

National Institute of Justice, was undertaken by Kip Schlegel and his research

associates at Indiana University (Schlegel, Eitle, and Gunkel, 1994). The topic of

this project was securities lawbreaking. To study securities fraud and the

enforcement response, Schlegel and his associates collected quantitative data on

enforcement actions taken by Self-Regulatory Organizations (National Association

of Securities Dealers, the NY Stock Exchange, and the American Stock Exchange),

the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the US Department of Justice.

Arguing that the study must consider fraud in its broadest context, the researchers

justify this approach by suggesting “it is a far more taxing yet potentially more

rewarding approach to try to examine what has not been caught, or what has been

caught by different means, and to study the net closely to determine the changes to

be made and the alternatives available” (Schlegel et al., 1994: 37).

The length of the available archival record varied, depending on the data

source. SEC enforcement actions (called “releases”) were bound and published in

a document called the SEC docket. These data spanned 1985 to 1991. DOJ data

on security actions were analyzed for the years 1984-1991. The self-regulatory

data extended from 1988 through 1992. All actions during these time periods were

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 33

extracted from the archival record for both individuals and companies. There were

relatively few of the latter, and they were found mainly in the administrative legal

realm—less so in criminal and civil actions.

13

Comparisons were made as to what

kinds of offenses were discovered and sanctioned, the nature of the offense, the

victim(s) involved, the distribution of offenses over time, perpetrator

characteristics (males, females, firm), and the distribution of sanction type over

time. The different data sources varied in their level of analysis. Civil cases were

case-based records while the criminal and administrative cases were organized by

individual defendant. Consequently, the study recorded the number of offenders

involved (including firms), but did not record each offender’s case disposition—in

part because most sanctions during the time of the study involved injunctions

(Schlegel et al., 1994: 39).

Analysis of the data focused on cases formally entered/actions initiated and

cases disposed and resolved. The researchers also tracked when administrative

actions involved a “parallel proceeding” in civil or criminal court. Like previously

discussed studies, Schlegel and his associates collected additional data from other

sources, including interviews with relevant enforcement staff and a written survey

administered to select offices of the FBI.

13

In the criminal area, only four cases involved firms or companies during the period of the study.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 34

Schlegel and his collaborators highlight some of the data difficulties they

encountered in their use of archival records. Specifically, they note that

information varied within and between the different archival sources. This fact,

coupled with the presentational and stylistic differences in the authors of the SEC

litigation releases, made it difficult to capture the same information from the

sources, create a consistent coding instrument, and reliably interpret the meaning

of the information (1994: 134). Undoubtedly, these problems are not unique to the

Schlegel study.

Karpoff Studies. Jonathan Karpoff and his colleagues have built a series

of detailed databases from publicly available data sources. These databases have

been created to investigate company (and in some cases manager) participation in a

variety of different corporate offenses (financial misrepresentation, bribery,

environmental violations), and to assess the legal and extra-legal consequences

associated with enforcement. To some degree, each research question generates its

own database because different crimes are of interest to the researchers. So, for

instance, if the researchers are interested in foreign bribery (Karpoff, Lee, and

Martin, 2014), a sample of publicly traded companies against whom enforcement

actions for foreign bribery have been initiated by the U.S. Department of Justice

(DOJ) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is generated. If financial

misrepresentation is of interest, the researchers generate a list of firms targeted by

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 35

SEC enforcement actions for financial misrepresentation (Karpoff, Lee, and

Martin, 2008). Environmental violations (Karpoff, Lott, and Wehrley, 2005)

follow the same process, but enforcement data are gathered from The Wall Street

Journal Index, under its "Environment" and "Environmental Crime" listings, and

NOT from the EPA (no doubt because EPA data are facility- and not firm-based).

Across all of the studies, there are common primary data sources from which

information is drawn:

[T]the SEC website (www.sec.gov), which contains SEC press and selected

enforcement releases related to enforcement actions since September 19,

1995; the Department of Justice, which provides information on

enforcement activity through a network of related agencies with particular

emphasis on high-profile enforcement actions available at www.usdoj.gov;

the Wolters Kluwer Law & Business Securities (Federal) electronic library,

which contains all SEC releases and other materials as reported in the SEC

Docket since 1973 and select Federal Securities Law Reporter releases from

1940 to 1972; Lexis-Nexis’ FEDSEC:SECREL and FEDSEC:CASES

library, which contains information on securities enforcement actions; the

PACER database, which contains lawsuit-related information from federal

appellate, district and bankruptcy courts; the SEC’s Electronic Data

Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) system; and Lexis-Nexis’ All

News and Dow Jones’ Factiva news source, which includes news releases

that reveal when firms are subject to private civil suits and regulatory

scrutiny (see Karpoff, Koester, Lee, and Martin, 2014: 10-11).

We call attention to the Karpoff data because it demonstrates that useful data can

be electronically scraped from publicly available sources, and that once collected

the data can be used for a multitude of different purposes. Over time, archival data

scraping will become even easier as more and different kinds of sources become

electronically available and increasingly sophisticated software becomes available.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 36

B. Applied Efforts

There are a number of archival data collection efforts in the white-collar

crime area that have been used by consulting firms to advise government, law

firms, and corporations about issues relevant to policy, regulation, and litigation.

National Economic Research Associates (economic consultants), for instance, used

data from FinCen enforcement actions and BankersOnline.com BSA/AML

penalties list to report on recent trends in Bank Secrecy Act and anti-Money

Laundering enforcement (2014). The data can be used to identify the types of

institutions targeted for enforcement actions, how patterns of enforcement have

changed over time for penalties with and without fines, counts of filings,

comparison of BSZ/AML with other kinds of Suspicious Activity Report (SAR)

activities (including check fraud, mortgage fraud, and identity theft), and the ratio

of SARs filings to enforcement actions, among other purposes. Similarly, NERA

recently published a report on securities class action litigation (Comolli and

Starykh, 2014) that utilized federal court filings to assess litigation trends. Case

filings were broken down by circuit courts, type of violation, foreign country

domicile and year, and by sector.

Consultants are not the only ones to utilize available data in the white-collar

crime area to generate reports and assist clients. The legal practice of Morvillo

Abramowitz Gran Iason & Anello PC has generated a document in which they

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 37

report on all of the SEC Enforcement Division’s new case filings for the entire

calendar year 2013.

There is little evidence that the data collected and utilized by consultants and

legal practitioners have been subjected to rigorous verification and validation.

14

Given what we know from our efforts at data cross-validation, there are apt to be

substantial source discrepancies as well as large amounts of missing cases and

information that affect overall comprehensiveness and quality of the applied

databases.

A somewhat different approach has been taken by the National White Collar

Crime Center (NWCCC). In association with the Bureau of Justice Assistance, the

NWCCC has administered three national victimization surveys, most recently in

2010 in which 2,503 adults reported (via telephone) household white-collar

victimization experiences within the past 12 months. The purpose of the survey is

to discern the prevalence and types of white-collar victimizations, whether victims

reported to law enforcement or other agencies that could assist victims, and

perceptions of crime seriousness. The 2010 survey, compared with earlier

versions, also offered a more comprehensive assessment of “corporate” crimes.

Unfortunately, and not unlike the previous versions, the telephone-based response

14

The different databases put together by Karpoff and his associates have been evaluated and cleaned for data

problems such as case redundancy and contradictory details (personal communication with Gerald Martin).

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 38

rate was very low (13% for the landline samples and 18% for cellular, Huff et al.

2010:38). Such low response rates seriously challenge comparisons between data

sources to determine convergent and nomological validity. As acknowledged by

the survey administrators, such deficiencies affect the ability “to assess the true

frequency of various types of white collar crime” (Huff et al. 2010: 13).

Even with these caveats, the authors of the survey compare victimization

rates from the 2010 survey to data from the 2008 National Crime Victimization

Survey to “show” the extensive nature of white-collar victimizations. The NCVS

“computed a victimization report rate of 135 households per thousand (13.5%) for

property crime and 19.3 individuals age 12 or over per thousand (1.93%) for

violent crimes. Even at an understated rate of 24.2% (for households), white collar

crime victimization is occurring much more frequently than property crime and

violent crime combined” (Huff et al. 2010: 22, emphasis added). Unfortunately,

such comparisons and conclusions are problematic. The NCVS has a response rate

of 95%, providing confidence that the property and violent crime rates are closer to

the true rates in the population. With a response rate of 13% and 18%, the

epistemic correlation for white-collar victimization will likely be low. And

although the NWCCC assumes that the numbers will understate the prevalence,

frankly it is unclear the direction in which the data might be biased. If the

respondents are interested to report their experiences with white-collar crime

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 39

because they have been victimized, the bias will move in the direction of over-

estimating—not underestimating—victimization levels.

Drawing from the survey results, what does “white collar crime” look like

from the perspective of the victim? On average, 24% of the respondents reported

some kind of white-collar victimization in their household within the past 12

months (respondents could report one or more victimizations per household).

Credit card fraud is the most commonly reported offense (38.7%), followed by

price misrepresentation (28.8%), unnecessary repair (22.8%), and monetary loss on

the internet (14.3%). More than half of the victimizations (54.7 %) were reported

to at least one entity but, because nearly 46% were not reported, there is likely a

great deal of bias in the cases known to authorities generally let alone law

enforcement specifically. Not surprisingly, because credit card fraud was the most

commonly reported victimization, credit card companies were notified most often

(30.9%), followed distantly by police (18.8%), banks (15.6%) and the perpetrating

business/person (14.8%).

For those interested in the hidden figure of corporate crime, the survey data

do not allow differentiating offenses committed by legitimate businesses

(organization or employee representing the company) from those perpetrated by

individuals or illicit organizations. Unfortunately, this is more than a simple

coding problem. It derives from how questions are constructed. For example, “In

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 40

the last 12 months, has anyone succeeded in getting someone in your household to

invest money or time in a business venture such as a work-at-home plan, a

franchise, or stock purchase that turned out to be fake or fraudulent?” Similarly,

“In the past 12 months, has someone in your household paid for repairs to a

vehicle, appliance, or a machine in your home that were later discovered

unperformed OR that were later discovered to be completely unnecessary?”

Crimes by businesses are bound with those committed by individuals or illicit

organizations. The problem is also compounded in the coded response categories

for reporting the victimization. To the question “To whom was this incident

reported,” a potential response category is: “Business/person involved in the

swindle.” In only one part of the survey (hypothetical scenarios) are legitimate

organizations and their employees differentiated from individual fraudsters, but the

differences between legitimate businesses and criminal enterprises remain

unexamined.

The differences between legitimate businesses/managers, individual

perpetrators of white-collar crimes, and illicit organizational schemes are important

to tease out. Conceptually, these are quite different and distinct offenders.

Importantly, the survey also reveals that white-collar offenses are viewed as

slightly more serious than traditional crime, and that organizational level offenses

are viewed more harshly than those committed by individuals, but we do not know

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

P a g e | 41

the mechanisms that drive the perceptions. Is it social organization, type of crime,

degree of harm, whether a business is licit or illicit? While more clarity is needed

to answer these key questions, the issues raised demonstrate the importance of not

mixing apples and oranges in this same way for a series on white-collar violations.

Overall, victimization surveys like the NWCCC effort appear better suited to

estimate the dark figure of non-corporate kinds of white-collar offending as these

acts are more likely to be recognized and reported by crime victims. Moreover, it

is extremely difficult to measure victimization at the corporate level. Although

corporations are often victims of price-fixing, industrial espionage, insider trading,

hacking, and employee theft, the firm (like individual victims) may not know it has

been victimized.

C. Broad Measurement Models