City University of New York (CUNY) City University of New York (CUNY)

CUNY Academic Works CUNY Academic Works

Student Theses John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Spring 5-16-2022

Red-Collar Crime: The Field Re-Examined Red-Collar Crime: The Field Re-Examined

Kortni MacDonald

CUNY John Jay College

, macdonaldkor[email protected]

How does access to this work bene<t you? Let us know!

More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/245

Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu

This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY).

Contact: AcademicWorks@cuny.edu

1

RED-COLLAR CRIME:

THE FIELD RE-EXAMINED

A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for

the Master of Arts in Criminal Justice

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

City University of New York

Kortni MacDonald

May 2022

2

ABSTRACT

Red-collar crime is an understudied phenomenon that occurs when white-collar crime turns into

physical violence and/or death (also known as fraud-detection homicide). Frank S. Perri, coined

the term red-collar crime following his study of 27 homicides that occurred at the same time as or

before the deadly white-collar criminal occurrences. This study explores the generalizability and

practicality of this definition as applied to a new set of cases. Using a case study analysis of six

cases this study analyzed the behavioral characteristics of these offenders meeting Perri's

definition; Characteristics such as entitlement, lack of empathy, power orientation,

rationalizations, exploitations, and a general disregard for rules and social norms were all found

in this sample in alignment with Perri’s theorized matrix. This study affirms the similarity of red-

collar offender behavior to street-level criminals suggested by Perri. Practical considerations and

suggestions for future research are provided.

Keywords: fraud, embezzlement, insurance fraud, corporate fraud, extortion, credit

card/automated teller machine fraud, blackmail/extortion, impersonation, welfare fraud, and false

pretenses/swindle/confidence game

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. 3

INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 4

RED-COLLAR CRIME ............................................................................................................... 6

WHITE-COLLAR CRIME AND ITS MISCONCEPTIONS ................................................................... 6

OFFENDER BEHAVIORAL PATTERNS AND ATTITUDES ........................................................... 10

RED-COLLAR BEHAVIORAL RISKS ................................................................................................ 12

INSTRUMENTAL AND REACTIVE VIOLENCE .............................................................................. 13

GENDER AND RED-COLLAR CRIME ............................................................................................... 14

INSTRUMENTATION .......................................................................................................................... 15

METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................... 16

RESEARCH QUESTIONS .................................................................................................................... 18

DATA ..................................................................................................................................................... 18

SAMPLE ................................................................................................................................................. 19

RED-COLLAR MATRIX ...................................................................................................................... 20

PROCEDURES....................................................................................................................................... 21

CASE STUDIES .......................................................................................................................... 23

AMY DECHANT ................................................................................................................................... 23

EDWARD WAYNE EDWARDS .......................................................................................................... 27

GARY W. PLOOF .................................................................................................................................. 29

LINDA LOU CHARBONNEAU ........................................................................................................... 31

LOUISE VERMILYEA .......................................................................................................................... 34

REV. JOHN DAVID TERRY ................................................................................................................ 37

RESULTS .................................................................................................................................... 39

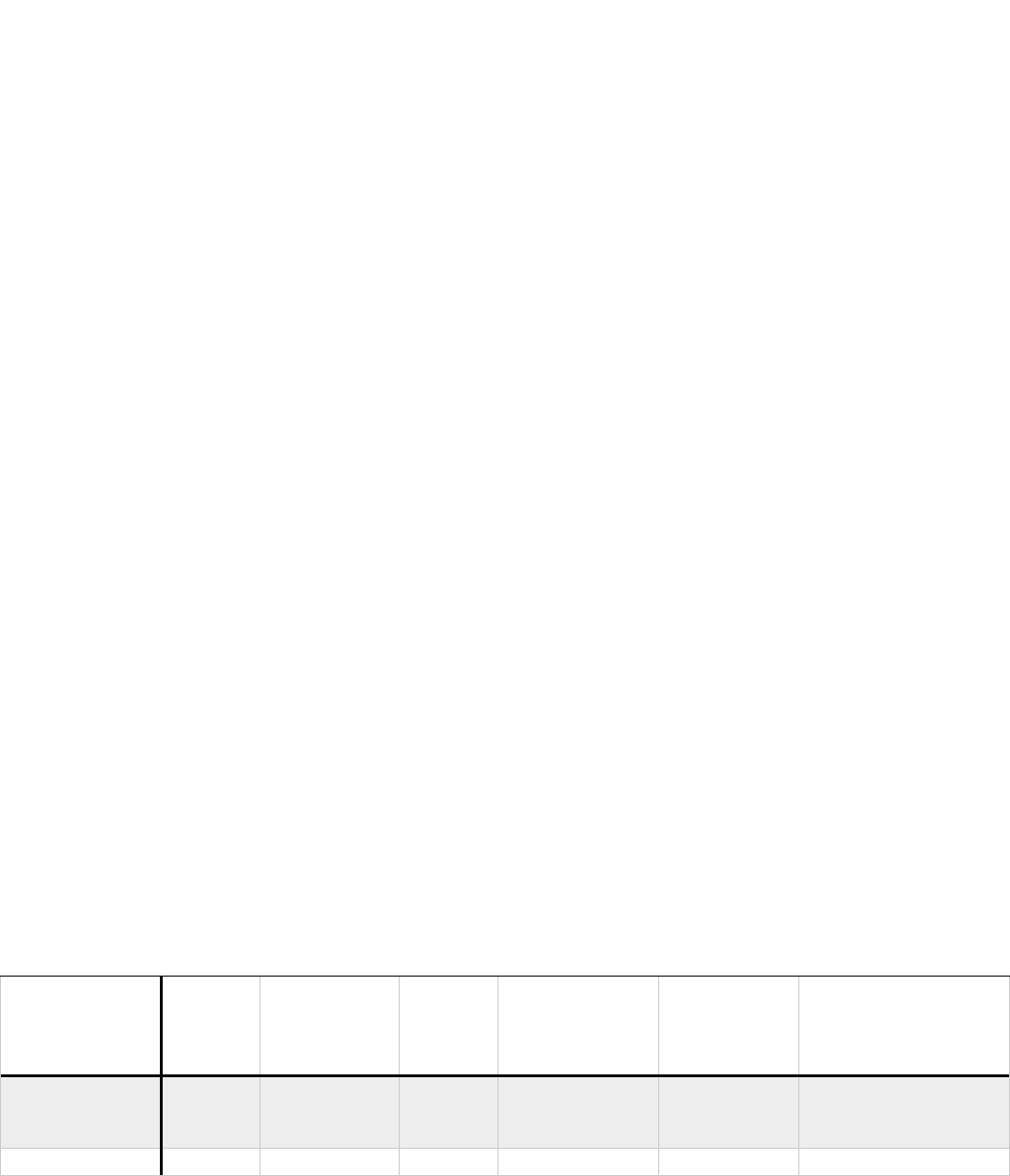

CASE STUDIES RED-COLLAR MATRIX .......................................................................................... 41

TABLE OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................... 43

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................... 45

WORKS CITED.......................................................................................................................... 51

APPENDIX A. ............................................................................................................................. 60

ORIGINAL TABLE RED COLLAR MATRIX ..................................................................................... 60

4

INTRODUCTION

Many scholars brought attention to the crimes of the powerful (Bonger, 1916; DuBois, 1967;

Ross, 1907; Van Erp, 2018), but Edwin Sutherland was the first to distinguish ‘white-collar’

criminals. In 1939, Sutherland conceptualized and defined white-collar crime while comparing

the upper and lower classes of society; he observed that high-society, respected businesspeople

were committing specific types of crimes (Sutherland, 1939). Sutherland later revised his

definition of white-collar crime to the now-familiar term, that of high-status people with great

power in their profession who commit fraud (Sutherland, 1949). Unlike street-level offenders,

white-collar criminals were once thought to be one-time offenders, but even these perpetrators

showed a high tendency toward rule-breaking behaviors (Benson and Kerley, 2001; Weisburd

and Waring, 2001). Current research suggests that the traditional stereotype of white-collar

criminals as single offense offenders may need an adjustment (van Onna, van der Geest, &

Denkers, 2020).

Society often fails to grasp what white-collar crime is because the field is rife with

misconceptions. The literature reviewed in this study will attempt to address these common

misconceptions and their potential consequences, as well as provide a brief overview of the

history and current definitions of white-collar crime. Current research shows that white-collar

criminals exhibit similar violent aggressive behaviors to non-white-collar criminals (Alalheto

and Azarian, 2018). Behavioral traits are important risk factors for street-level forms of crime;

the potential application to white-collar crime makes logical sense (Listwan, Piquero & Van

Voorhis, 2010).

5

In further research on white-collar crime, subcategories of the subject came to the surface.

Take, for example, the phenomenon of red-collar crime. Frank S. Perri was the prosecutor in the

2004 homicide trial People of the State of Illinois v. George Hansen. In this case, the defendant

killed his business partner to avoid detection of a fraud scandal (Hansen, 2004). The disclosure

of the motive for this case piqued Perri's interest in white-collar crime. He wondered if these

white-collar criminals constituted a new subgroup of criminals. He collected homicide cases with

similar motivations. He searched legal documents, such as murder trials disclosed in newspapers,

and public court sentences in which white-collar criminals were convicted of homicide or

attempted homicide. Perri discovered that academic research has few studies on white-collar

criminals with respect to their motives and behavioral patterns. Continuing, Perri also discovered

that violent white-collar criminals, not being strange anomalies, harbor behavioral risk factors.

These factors promote their use of violence as a solution to their problem. This issue is no

different from non-white-collar offenders that resort to violence, even if they have different

motives (Perri, 2015). Owing to his involvement in the 2004 Hansen case and research

discoveries in 2005, Perri described white-collar criminals who turned violent as ‘red-collar’.

Red-collar and white-collar criminals should not be confused as being the same type of

criminal. White-collar criminals have a mixed history of white-collar and non-white-collar

crimes that may include violent histories. The motive behind the violence determines the

criminal subgroup as red-collar. Offenders engage in violence to silence those that threaten

detection or disclosure of their fraudulent schemes. 'Fraud detection, homicide' also classifies

this type of homicide as well. Several written judicial opinions and case facts from investigation

and prosecution disclosures provide evidence of the planned nature of this crime. A review of

these case facts supports several conclusions as to the underlying motive (Perri, 2015). There are

6

no longitudinal studies on the number of committed red-collar crimes. Past studies focused on

descriptive statistics such as age, gender, race, frauds preceding the homicide, victimology, and

behavioral make-up, to name a few. Perri believes it is advantageous to begin the conversation

about red-collar crime, as his own study offers a template to refine and clarify the criminal

profile (Perri, 2015).

RED-COLLAR CRIME

Current research on red-collar crime shows that these offenders are willing participants in

acts of violence. This violence may manifest in the use of firearms, controlled substances,

manual strangulation, and blunt force trauma. These criminals have also proven willing to sign

for murder-for-hire cases on their behalf (Perri, 2019). Red-collar crime is a newly defined

subgroup of white-collar crime. I want to explore any gaps that may exist in the literature. To do

so, I will describe what white-collar crime is now, and any misconceptions that may still exist.

Doing this will investigate the reasons why red-collar criminals are willing to commit acts of

violence. Describing white-collar criminal behavioral characteristics will shed light on that of a

red-collar criminal as well.

WHITE-COLLAR CRIME AND ITS MISCONCEPTIONS

Sutherland believed that white-collar crime is a crime committed by the upper echelons

of society. These people usually have a big influence on their business. (1949). Today, scholars

define white-collar crime as crimes committed by financial elites who abuse the trust and power

that have been given to them in their careers (Benson and Simpson 2015; Dearden 2017; Piquero

2012). What the phenomenon of white-collar crime is and how to measure it is still widely

7

discussed by scholars. However, much of Sutherland's original stances (1934, 1940, 1949, 1973,

1983) are still found to be true now (Simpson, 2019).

As I engage in the use of current knowledge of white-collar crime, I will look at

Sutherland's findings from a retrospective lens. Because his influence on white-collar crime is so

wide-ranging, a lot of misunderstandings can arise. White-collar crime reflects high levels of

corporate misconduct and occupational fraud schemes among middle-class citizens (Weisburd et

al., 1991). This combined with predatory offenses (Bucy et al., 2008) are keys to Sutherland's

perception of this white-collar offender. It is important to stress that some aspects of his work

have stood the test of time; take, for example, his use of a life history approach (Simpson, 2019;

Friedrichs, Schultz, and Jordanoska, 2018). The life history approach examines how one’s

personal history effects their future decisions and behaviors; this is the approach he used when

he studied corporate criminals (Laub, & Sampson, R. J. 2019). However, current research has

shown that Sutherland’s research has been shortsighted on important developments that he could

not have foreseen, such as motivations (Simpson, 2019). One of Sutherland’s most important

criticisms can be found in his analysis of crime data. To him, the crime data did not capture

crimes committed by businesses. This issue creates a bias in the data (1949). This bias may lead

to a general misunderstanding of the topic due to bridge gaps in such data and current findings in

the field.

Society perceives illegal behavior to be out of character for white-collar criminals

because we view them as employed, educated, and law-abiding citizens. These criminals may

also present positive ethical behaviors in areas of their lives, and thus are less likely to be

categorized as having criminal behaviors despite the severity and consequences of their crimes

(Brody, Melendy, & Perri, 2012). Scholars and behavioral science experts did not apply criminal

8

thinking traits to white-collar offenders in the past, unlike non-white-collar offenders, so this

misconception continued for decades. Efforts were focused on examining index crimes such as

property, narcotics-related crimes, violence, and theft (Lilly, Cullen, & Ball, 2011). Scholars also

drove their focus toward the social processes within an organization that might serve as "risk

factors for fraud to flourish" (Sutherland, 1949, p. 19). In doing so, they rejected individual

personality traits as potential fraud offender risk factors (Perri, Lichtenwald, &; Mieczkowska,

2014). White-collar and non-white-collar offenders display persistent criminal thought patterns

and attitudes about circumstances to exploit (Samenow, 1984).

It is important to understand the criminal thinking of white-collar crime, however, this

requires debunking the myth that these types of offenders do not represent similar criminal

groups. White-collar criminal histories and levels of deviance are no different from non-white-

collar criminals (Walters, & Geyer, 2004). Not many white-collar studies have been conducted

to discuss behavioral consistencies following their careers over a long period of time (van Onna,

et al., 2020). These life-course studies show that only a few cases have consistent criminal

behavior. Most of these white-collar offenders are categorized by low-frequency offending

(Benson and Kerley, 2001; Van Onna, van der Geest, & Denkers., 2014; Weisburd and Waring,

2001). A lack of understanding of this type of criminal thinking may help the criminal

community. It may block specific searches for criminal activity that can be used to define red-

collar trends (Perri, 2015).

In investigating these current white-collar trends, I will consider the evolution of white-

collar crime. The reasons and motivations behind the white-collar crime are an enduring

criminological conundrum (Jordanoska, 2018). Understanding the social psychology of one's

fraudulent behavior is grounded on, but not limited to how an individual reacts to the instability

9

of preferences, (Maulidi, 2020). Like street criminals, white-collar criminals are motivated by

need, greed, fear of failure, revenge, excitement, and economic survival (Jordanoska, 2018).

Abundant criminal motives can more successfully deepen our understanding of white-collar

crime than linear motives such as self-control (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1987) or culture of

competition found exclusively in white-collar crime (Coleman, 1987). This data is important to

collect to understand these motives.

To improve our reach in data, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) promptly

supplies data on white-collar crime in the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR); tracking any

statistical data can help to identify the baseline to the criminal profile. The UCR provided by the

FBI, documents only a small number of white-collar crimes. There is not a current national

database provided by the U.S. Department of Justice for white-collar crime statistics. There is

also a lack of a central repository that reports an annual collection, tracking, and reporting of

white-collar crime statistics that cover a wide variety of white-collar offenders and their offenses

(McGurrin, et al., 2003). Incident-based statistics are collected by The National Incident-Based

Reporting System (NIBRS). A restricted record of white-collar criminal arrest accounts of

bribery, embezzlement, forgery, and fraud—offenses represented at the individual level. (Barnett

2000). The FBI examined challenges with these offenses. They specifically noted that both

NIBRS and UCR had been developed with the state and crime data interests in mind. The FBI

did not keep the interests of researchers in mind because white-collar offenses typically fall

under the jurisdiction of federal agencies. Many white-collar crime categories are not included

(McGurrin, et al., 2003). The lack of regard for white-collar criminal thinking supports the

assumption that these offenders may use this vulnerability to expose and target victims. These

crimes may be perpetrated by the same people believed to not have the capacity to resort to

10

violence and criminal actions. Behavioral risk patterns and personality traits must be studied so

that we may further our understanding of white-collar criminals.

OFFENDER BEHAVIORAL PATTERNS AND ATTITUDES

Forensic criminal psychologist Dr. Stanton Samenow warns academics/readers against

the idea that crime is out of character for an offender because of their lack of criminal history or

societal offenses. He warns against using the ideas such as a strong employment record and the

appearance of being an upstanding member of society as a basis of character (Samenow, 2010).

Life-course studies on the white-collar offenders have revealed that once criminally active, these

offenders show less crime specialization than previously thought (Benson and Moore, 1992; Van

Onna et al., 2014). Self-reporting studies have indicated that misconduct levels, both inside and

outside of the workplace, may be higher than their criminal records show (Menard, Morris,

Gerber, & Covey., 2011; Morris and El Sayed, 2013). This premise holds true to both white and

non-white-collar offenses (Perri, 2013). Historically, it was believed that white-collar criminals’

illegal actions are out of character. However, years of research conducted by Samenow,

described that there has yet to be an observable case where the person is acting out of character.

His research also points out that there is a persistent lack of complete information surrounding

aspects of a criminal’s behavior period. For example, behavior such as deviant thought processes

may predate their offenses and have existed for a long time. The offenders may have been

repressing these unnerving thoughts in wait for an opportunity to present itself (Samenow, 2010).

The fact that the offender has chosen to engage in certain acts does not mean that it is

outside of one’s character. It also does not mean that those anti-social traits cannot be revealed

through their actions (Perri et al., 2014). These people use a cost-benefit analysis or risk

11

assessment to sort through their actions. This response is the stage where they decide if

committing the crime is worth the costs (Shover & Wright, 2001). People at all socio-economic

levels have the potential to display criminal anti-social attitudes. Many scholars have begun to

apply criminal thinking attributes to white-collar criminals, but Sutherland is the first (Gaylord,

& Galliher, 2020). Criminal thinking is defined as a concentrated or distorted thought pattern that

involves values and attitudes that support criminal actions and lifestyles (Walters, 2020). These

thoughts justify and rationalize law-breaking behaviors. (Taxman, Rhodes, & Dumenci, 2011).

Criminal thinking was a stressed role in the support, maintenance, and reinforcement of adult

criminal behavior (Walters, 1990). Commonly displayed criminal traits often include but are not

limited to, entitlement, lack of empathy, power orientation, rationalizations, exploitations, and a

general disregard for rules and norms (Walters, 1995). Not only limited to one group, but

criminal thinking and anti-social traits also apply to both white and red-collar offenders (Walters,

2002; Walters & Geyer, 2004; Perri & Lichtenwald, 2007). Those who commit white-collar

criminal acts are often just as likely to be repeat offenders as non-white-collar offenders

(Weisburd, Warring, & Chaye, 2001).

Studies have shown that recidivism rates are comparable between white-collar and non-

white-collar crime (Weissmann & Block, 2007), both types of offenders possess thinking and

criminal deviancy traits that are virtually identical to one another, especially among chronic re-

offenders (Walters & Geyer, 2004). White-collar criminals become more comparable to street-

level criminals when there is an observable pattern of fraudulent activities. This new comparison

puts them into the category of being viewed as predators or pathological criminals. (Dorminey et

al., 2010).

12

RED-COLLAR BEHAVIORAL RISKS

In his research, Perri highlighted the personality traits of red-collar criminals. These traits

point out the increased risk of committing crimes such as embezzlement, tax evasion, or fraud in

the white-collar community. He pointed to psychopathic and narcissistic traits, which he claimed

were key to the rise of white-collar crime turning red (Alalheto, & Azarian, 2018). These

characteristics will be particularly focused on for this study as well.

Psychopaths are characterized by their self-centeredness. They possess attitudes of

manipulation, deception, and exploitation, and their means always justify the ends, regardless of

the crime (Ray, 2007). They minimize the harmful consequences of their actions, neutralize their

wrongdoings with superficial justifications, and tend to blame their victims for their actions

towards them. Psychopaths possess the ability to lie without feeling uncomfortable, and they can

manipulate people with high-quality interpersonal skills. This quality allows them to easily

persuade their victims (Boddy, 2006; Hare, 1993; Ray, 2007).

Narcissism is a personality disorder that involves a strong sense of self-confidence; it is

exaggerated by the overt feeling of excessive admiration, self-importance, and a lack of empathy

for others. Narcissistic people have an exaggerated conception of their abilities and potential.

They believe that they are superior and unique, which drives their need for gratification for their

achievements. These people value themselves over others to the extent that disregards the wishes

and feelings of others (Alalheto, & Azarian, 2018). They tend to be exploitative of people's

personal gains and achievements, fostering their interpersonal relationships in a manipulative and

excessively instrumental fashion. Their extreme sense of entitlement impels them to believe they

have special privileges over ordinary people (Perri, 2011). White-collar criminals may possess

these qualities and knowing this may provide clarity to the red-collar criminal profile.

13

The misconceptions that surround the white-collar profile are starting to be corrected.

Research is beginning to define this offender group in a way that is not based on opinion (Perri,

2015). It has become increasingly clear that the white-collar offenders choose different

aggressors to satiate their daunting motives, which at times can and do involve using forms of

violence to solve their problems. Research suggests that any personality and behavioral traits

should no longer be ignored because they may be subject to possibly murderous white-collar

behavior lurking below the surface (Ragatz, Fremouw, & Baker, 2012). Important violation

pattern factors in observations can easily be overlooked, which can quickly become problematic.

Evidence explains that there is a significant relationship between an anti-social disposition and

the underlying confirmation of narcissism and psychopathy. When combined with a criminal

mindset, this event creates a negative relationship. This response then increases the risk of white-

collar criminal behavior (Perri & Brody, 2012).

INSTRUMENTAL AND REACTIVE VIOLENCE

Next, I compared accusations of instrumental violence and accusations of reactive

violence. When the offense is goal-oriented first, the homicide will be rated under the use of

instrumental violence. There may be no evidence of direct situational or emotional provocation.

Instrumental violence has a means to an end, this eventuality is violence served directly by

motive (Hart & Dempster, 1997). This evidence of a gap in time between the frustration or

provocation, (also known as a cooling-off period) and the murder, classifies the homicide as

using instrumental violence (Woodworth & Porter, 2002). For a homicide to be rated as reactive

violence, there must be irrefutable evidence that the crime was committed at a high level of

spontaneity and lacked planning or premeditation. This eventuality is considered a rapid reaction

14

before the act of murder with no specific goal other than to immediately harm the provocation

(Perri, 2015). Reactive violence often occurs between family members and acquaintances, as

opposed to instrumental violence where it often occurs between strangers.

GENDER AND RED-COLLAR CRIME

Restricting work to men in the past has left a huge gap in understanding how women may

think differently of offending parties. Research suggests that women are unlikely to take part in

any large white-collar schemes. They tend to participate in more subordinate roles (Benson &

Gottschalk, 2015) Steffensmeier, Schwartz, & Roche, 2013). Feminine gender norms to inherent

concern for others may explain displacing responsibility for these types of offenses.

A study comparing men and women in criminal thinking suggested a general similarity

between the two genders. However, evidence showed that women scored slightly higher than

men on individually scored components. This similarity in thinking styles is striking given the

offense distribution is uneven across white-collar crimes. Take, for example, embezzlement. It is

nearly twice as likely to be committed by young females compared to men (Galvin, 2020). This

suggests that, despite gender norms, there is little difference in the cognitive process between

male and female offenders that are charged with white-collar offenses, however, women remain

less involved in criminal activity, and this includes white-collar offenses (Belknap, 2001).

Women, too, exhibit antisocial behaviors (Dolan & Vollm, 2009) along with varied personality

disorders (Warren & South, 2006).

This issue suggests that criminal thinking in red-collar cases may present the same risk

factors across genders (Perri & Lichtenwald, 2010). For example, psychopathy is displayed by

both genders (Cleckley, 1976). However, research has typically been conducted under the male

15

assumption, rather than including female studies (Skeem et al., 2011). There are several clinical

accounts of female psychopaths. While admittedly there is very little empirical research on

female psychopathy (Carozza, 2008), stereotypes and rigid sex roles in society and the diagnosis

of personality disorders are to a large extent influenced by sex-role expectations. This idea may

be the reason for neglect in the research (Widom, 1978; Brown, 1996). Males and females who

display psychopathic tendencies share similar affective and interpersonal features, this issue can

include egocentricity, deceptiveness, shallow emotions, and lack of empathy (Carozza, 2008).

INSTRUMENTATION

This study uses Frank S. Perri’s Red-Collar Matrix (RCM) to conduct a case study

analysis. Several pattern characteristics are on the Perri-RCM that are used to examine the new

cases. “The Perri-RCM was developed to distinguish behavioral inferences from other evidence

gathered during both the investigation and subsequent trials. Clearly, the pattern characteristics

in the Perri-RCM are not all-inclusive, and as more cases are analyzed, the Perri-RCM can be

modified to accommodate additional characteristics that may be useful for profiling” (Perri &

Lichtenwald, 2007, p. 20). Every case where the defendant had been involved in fraud will be

listed under the last name which will appear at the top of the matrix. An example of the matrix

will be provided in the appendices, showing the original Perri-RCM.

Red-collar criminals share similar psychopathic tendencies as non-violent white-collar

offenders. The biggest difference between the two criminals is the factors in the red-collar

criminal's character that allow them to see violence as a viable solution (Belmore & Quinsey,

1994). Many white-collar psychopaths have antisocial traits. However, this fact is different from

violent traits, which are found in red-collar criminals. Men and women possess the ability to

16

demonstrate these traits (Perri, & Lichtenwald, 2007). The phenomenon of white-collar crime

turning red is an idea that should be recognized by scholars. Understanding the evolution from

one to the other may help to prevent violent crimes by being able to recognize these

characteristics in fraud accounts before it reaches the point of violence.

Matrices like the one Perri Used for his profiling tool are used in social sciences explore

relationships between individuals and populations. Relationships are not this simple, but matrices

allow one focus on specific characteristics. (Bradley & Meek, 2014). The use of the Perri-RCM

in this case maps out the relationship between behavioral pattern characteristics and the people

that are being assessed.

METHODOLOGY

Perri's research and introduction to red-collar crime are what inspired this study. This

thesis will be a qualitative case study analysis to determine whether different cases can satisfy

his description of red-collar by satisfying the same definitions and behavioral characteristics he

described in the original case study. A sample of homicides in the United States provided 100

cases for analysis. I searched each case using key terms (fraud, embezzlement, insurance fraud,

corporate fraud, Ponzi schemes, racketeering, and bankruptcy) to determine if they qualified as

white-collar crimes. If any of these terms appeared on the docket, the behavioral characteristics

and motivations were further analyzed to determine whether they fit the definition of a red-collar

crime. An analysis of these cases is used to understand whether the concept coined by Perri is

applicable to other cases.

6 of the 100 cases involved the key terms listed above. These cases are the focus of the

case analysis. The knowledge found from this study is important because it sheds new light on

17

the current red-collar criminal research. Perri claims that this group of criminals is not

anomalous. However, my findings suggest that they only represent a small number of homicidal

offenders. I only found that 6% of the offenders in this sample included white-collar

terminology. After further analysis, only 4% of the cases met the definitions of a red-collar

crime. The use of Murderpedia as a source for offenders limited this study because it is a

crowdsourced encyclopedia. Crowdsourced means that the information posted from this source is

not checked for accuracy. However, this source creates access to a list of perpetrators that could

be randomized. Knowing this limitation, I collected all case facts from public records, court

cases, police records, and news releases outside of the encyclopedia. I want to better understand

what motivates a white-collar criminal to turn violent. Red-collar crime is by far the best

description I have come across, and I wanted to explore the concept further.

To continue research in the field of red-collar crime, I propose this qualitative study. A

sample of 100 homicide cases derived from Murderpedia is analyzed for the presence of white-

collar terminology. 6 out of 100 cases met the necessary white-collar definition. These cases are

the focus of this qualitative review and are analyzed against the behavioral pattern characteristics

in Perri's original Red-Collar Matrix. The perpetrator's motives were disclosed under the further

analysis of each case. As mentioned earlier, motive plays an important role in the definition of a

red-collar crime. Next, I analyzed each case to determine the point in time when the fraud

occurred. To meet the definition of a red-collar, the fraud must be committed before or at the

time of the homicide. Succeeding this round of analysis, it was discovered that only four of the

six focused studies met all requirements of red-collar crime. This study will explore whether his

description of red-collar crime applies to a new set of cases. I am interested in whether his

18

definitions will apply to these and what percent of red-collar crimes exist among different types

of homicides.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

• Is this definition of red-collar crime practical and generalizable when applied to a new set

of cases?

• Does this study affirm similarities of red-collar offender behavior to street-level criminals

as suggested by Perri?

o What are these similarities?

DATA

Data Sources by Case

Amy DeChant:

• Court Cases: DeChant v. State of Nevada

• News Sources: The Naked & The Dead: Killer Amy DeChant Found in Nudist Camp,

New York Daily News; Woman Gets 25 Years for Killing of Live-in Boyfriend, The Las

Vegas Review; Fugitive Suspect in Weinstein Murder Arrest, Las Vegas Sun

Edward Wayne Edwards:

• News Articles: Elderly Conman Confesses He Killed 4 During Career as Motivational

Speaker, ABC News; Serial killer Edward Wayne Edwards sentenced to death in Geauga

County slaying. Cleveland Plain Dealer

• Books: IT'S ME: Edward Wayne Edwards, the Serial Killer You Never, Heard Of;

Metamorphosis of a criminal.

• Police Records: FBI’s Most Wanted

Gary W. Ploof:

• Court Cases: Ploof v. State

19

• News Articles: Life, while awaiting death, for convicted killer Ploof, Bay to Bay News;

Court Affirms Death Sentence for Wife Killer, Courthouse News Service

Linda Lou Charbonneau:

• Court Cases: Charbonneau v. State of Delaware

• News Articles: Three arrested for Delaware murders, The Rutland Herald; Charbonneau

Sentenced to Death. The Sussex Bureau Reporter.

• Public Records: Delaware Public Records: Linda Lou Charbonneau

Louise Vermilyea:

• News Articles: MRS. VERMILYA TRIES TO POISON HERSELF; Widow Accused of

Killing Policeman, and Suspected of Poisoning Eight Others, Near Death, The New York

Times; Barrington angry over poisoner case: Mrs. Louise Vermilya, Lake County

Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun; POISON IN PEPPER CAN, The Herald

Democrat; Louise Vermilya, Chicago Tribune

Reverend John David Terry:

• Court Cases: John David Terry v. State of Tennessee

• News Articles: Pastor Charged with Murder in Headless Body Case, AP News; Minister

Sentenced to Death - The New York Times

SAMPLE

To explore Perri's definition of red-collar crime, a set of new cases was created. I used

Murderpedia, an online crowdsourced encyclopedia that organizes murderers by state. The tool is

a crowdsourced encyclopedia, so it is only used to provide the names of criminals in the United

States. A random selection of 10 states was selected from Murderpedia using a United States

20

random state generator: Nevada, Tennessee, Louisiana, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Illinois, Indiana,

Wyoming, Delaware, and Ohio. Murderpedia also separates its offender list by the binary

gender, male and female. Both lists of offenders were assigned individual numbers. Using a

random number generator, 10 male and 10 female offenders were selected, creating a list of 20

offenders from each state. After using a random number generator again, 10 numbers were

selected from the new list of 20. This process was repeated for each state, finally giving a sample

of 100 homicide cases. Once the final list of murderers was collected, all cases were analyzed for

the use of key terms involving white-collar crime (Fraud, False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence

Game, Corporate Fraud, Embezzlement, Credit Card/Automated Teller Machine Fraud,

Extortion/Blackmail, Welfare Fraud, Impersonation, Wire Fraud). The details from each case

were derived from public records, police reports, and case notes. Succeeding preliminary

analysis, 6 out of the 100 cases were found to contain aspects of white-collar crime. Following

with another round of analysis that focused on the discovery of red-collar behavioral

characteristics from Perri’s RCM, only 4 out of the 100 cases met the criteria of red-collar

definitions.

RED-COLLAR MATRIX

This study explores the red-collar phenomenon. Second, it seeks to determine if Perri's

descriptions of these types of criminals are when using a new sample uses Frank S. Perri’s Red-

Collar Matrix (RCM) to conduct a case study analysis. Several pattern characteristics are on the

Perri-RCM that are used to examine the new cases. The RCM was created to distinguish

behavioral characteristics from evidence gathered during the investigation and subsequent trials.

He acknowledges that the pattern characteristics in the matrix are not all-inclusive. This matrix

21

can be modified to accommodate additional characteristics that may become prevalent to this

criminal profile (Perri & Lichtenwald, 2007) Every case where the defendant is involved in fraud

will be listed under their name which will appear at the top of the matrix. An example of Perri's

original matrix is provided in the appendices. A new matrix using the same pattern

characteristics as Perri's RCM and the new names of the current cases will be used to collect

data.

PROCEDURES

Each of the 100 cases went through the random selection process as earlier described,

deriving from a population set forth by Murderpedia. Knowing the limit set by using a

crowdsourced tool, only public records, news articles, and case files are used as data sources to

fill in the matrix. Each case is initially analyzed for any white-collar definitions provided by the

FBI (Fraud, False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game, Corporate Fraud, Embezzlement, Credit

Card/Automated Teller Machine Fraud, Extortion/Blackmail, Welfare Fraud, Impersonation,

Wire Fraud). After separating potential white-collar cases from the rest, these cases are further

searched for Perri's defined red-collar behavioral patterns. For the case to be considered red-

collar, fraud must predate or occur at the same time as the homicide. In some respects, the

suggestion that the red-collar criminal is willing to risk exposure to maintain anonymity appears

contradictory. Yet, the inclination to physical violence as a solution distinguishes these fraudsters

from non-violent white-collar criminals.

Specific terms are used to search through and identify the sample from the Murderpedia

population to ensure they fit the criteria of the definition set forth by Frank S. Perri of red-Collar

crime. The terms and their definitions provided by the FBI are as follows (FBI, 2012):

22

• Fraud: “The intentional perversion of the truth for the purpose of inducing another

person or other entity in reliance upon it to part with something of value or to

surrender a legal right. Fraudulent conversion and obtaining of money or property by

false pretenses. Confidence games and bad checks, except forgeries and

counterfeiting, are included.”

• False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game: “The intentional misrepresentation of

existing fact or condition, or the use of some other deceptive scheme or device, to

obtain money, goods, or other things of value”

• Corporate Fraud: “The falsification of financial information, insider trading, and

schemes designed to conceal corporate fraud activities and impede the regulating

bodies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission from conducting their

inquiries”

• Embezzlement: “The unlawful misappropriation or misapplication by an offender to

his/her own use or purpose of money, property, or some other thing of value entrusted

to his/her care, custody, or control”

• Credit Card/Automated Teller Machine Fraud: “The unlawful use of a credit (or

debit) card or automated teller machine for fraudulent purposes”

• Extortion/Blackmail: “To unlawfully obtain money, property, or any other thing of

value, either tangible or intangible, through the use or threat of force, misuse of

authority, threat of criminal prosecution, threat of destruction of reputation or social

standing, or through other coercive means”

• Impersonation: “Falsely representing one’s identity or position and acting in the

character or position thus unlawfully assumed, to deceive others and thereby gain a

23

profit or advantage, enjoy some right or privilege, or subject another person or entity

to an expense, charge, or liability which would not have otherwise been incurred”

• Welfare Fraud: “The use of deceitful statements, practices, or devices to unlawfully

obtain welfare benefits”

• Wire Fraud: “The use of an electric or electronic communications facility to

intentionally transmit a false and/or deceptive message in furtherance of a fraudulent

activity”

CASE STUDIES

AMY DECHANT

Amy DeChant (white, age 49) was charged with murder in the first degree in December

of 1998. She had killed her boyfriend Bruce Weinstein (white, age 46) for the large sum of

money that was in his possession. In 1995, DeChant was the operator of a cleaning business in

Las Vegas, Nevada. Here, she became romantically involved with Weinstein, an illegal

bookmaker. Illegal bookmakers are bookmakers that accept bets based on agreed odds. They

take bets from people and collects or pays out on the book they have created to detail who owes

whom (Foley, 2022). The two met in the fall of 1995 and days after, she sold her condo and

moved in with Weinstein.

DeChant grew up in a small township of New Jersey. The two-time divorcee moved to

Las Vegas in 1992. Those that knew DeChant were aware that she was highly financially

motivated as opposed to romantically in her relationships. As reported by the NY Daily News a

former boyfriend recalled, “She loved money. All she ever used to say is, 'I want to retire. I want

to retire. I want to retire." (NY Daily News, 2010, p. 5). On July 5, 1996, Weinstein had

24

disappeared. In the beginning, DeChant claimed that he left for the night and did not return,

however, Weinstein’s mother did not buy into this story. Later, DeChant changed her

recollection of events. She claimed that four mob hitmen had entered the home, killed Weinstein,

and threatened to kill her if she told anyone what they had done. After a private investigator was

hired by Weinstein’s family, DeChant’s new story began to unravel. The day after her second

testimony, DeChant fled. Investigators uncovered that she had found Weinstein’s cash stash

along with his sports book’s chips and jewelry. (DeCHANT v. The STATE of Nevada, 2000).

On August 11, Weinstein's body was found with a bullet wound from a .38 caliber gun.

This event resulted in a fugitive order being issued on DeChant. About a month following, she

was pulled over for speeding in Maryland. She was arrested, but because she had not been

charged with murder, her bail was only set at $5,000. She paid this immediately with Weinstein’s

money and fled again. DeChant avoided detection for over a year, but she was eventually found

in a nudist colony in Florida (Thevenot, 2001).

The prosecution for this case presented their findings attempting to prove that DeChant

had killed Weinstein because he threatened to end the relationship, and she did not want to give

up the lavish lifestyle she desperately craved. She was convicted for first-degree murder in

October 1998 and sentenced to life in prison without parole. However, this conviction was

overturned in 2000. Rather than going through a second lengthy trial, DeChant took a plea of

second-degree murder (NY Daily News, 2010).

DeChant had an unfortunate upbringing, as she lost both of her parents by the age of nine.

She was predominately raised by her aunt in New Jersey. DeChant’s first marriage was at 17, to

her high school sweetheart. DeChant’s marriage did not last very long. She developed a history

of dating men who had money, the next one was always wealthier than the last (Thevenot, 2001).

25

She does not meet the definition of a red-collar criminal. Her case did include fraudulent crimes,

specifically, she was associated with Weinstein's embezzlement schemes. However, most of

these actions were done by Weinstein, and she was only connected. An investigation into

DeChant uncovered these fraudulent schemes. Like street-level criminal motives, she is hungry

for money. She went to Weinstein for his wealth. When Weinstein caught onto what her motives

were, DeChant killed him to steal anything of financial worth Weinstein left behind. She

continued to cover her tracks by using the money she had taken from him to avoid prosecution.

Even though DeChant's case does not qualify as a red-collar crime, it is used to compare

to the others that do. Using the characteristic patterns in Perri's RCM, DeChant's datum

displayed most of the same characteristics, such as a lack of criminal history, no known mental

disorders, and had a murder plan. During the first analysis of this case, it was uncovered that she

was connected to an underlying white-collar embezzlement scheme through her boyfriend

Weinstein (DeCHANT v. The STATE of Nevada, 2000). This fact pushed her case through to the

second round of analysis. During this phase, the matrix was used to point out behavioral patterns

in the investigation and trial phase. It was discovered that DeChant used a .38 caliber to fatally

shoot Weinstein in the chest (Thevenot, 2001). The shooting had taken place at Weinstein's

home in Las Vegas (DeCHANT v. The STATE of Nevada, 2000).

Weinstein’s body was found in the desert near Mesquite, Nevada. When Weinstein's

body was found, a search for DeChant began along with an investigation into her past. During

this investigation, investigators discovered that she was aware of Weinstein's embezzlement

scheme and profited from it (DeCHANT v. The STATE of Nevada, 2000). Unlike Weinstein,

DeChant had no criminal record. She was seen as having a hunger for money (NY Daily News,

26

2010). She ran a successful carpet cleaning business, a blue-collar business (Thevenot, 2001).

There was no evidence discovered to suggest she had any debt problems.

During her trial, the jury found her guilty, and she was charged with murder in the first

degree. DeChant had incriminated herself through false testimony when she claimed that the

murder had been committed by the mob. The State provided expert witness testimony from

former Las Vegas Metropolitan Detective Alfred Leavitt stating, "Based on that experience and

that included some 30 years as a police officer and hundreds of such investigations, he examined

the statement given by Ms. DeChant to the police and pointed out several particulars in which

her version of what happened was not credible as involving a mob hit" (DeCHANT v. The

STATE of Nevada, 2000, p. 3). DeChant used this story of a mob hit in an attempt to conceal any

evidence leading the murder back to her. However, blood, gunpowder, and DNA evidence

proved that she was at the scene of the crime and pulled the trigger. She had planned this murder

and attempted to come up with a compelling cover story (DeCHANT v. The STATE of Nevada,

2000). In 2000, the original conviction was overturned, and she took a plea deal admitting to

second-degree murder.

Based on this evidence, DeChant fits several of the same characteristics of a red-collar

criminal. What sets her apart from red-collar criminals is that she did not run a fraudulent

scheme before or at the same time as the killing. Her case provides a great example of the

similarities in behaviors and motives between street-level homicides and fraud-detection

homicides. Similar to Perri’s findings, DeChant displayed narcissistic behaviors. For example,

she displayed behaviors of over self-importance and a lack of empathy for others. Narcissistic

people have an exaggerated conception of their abilities and potential. This was shown when she

assumed that she could hide from the authorities and prosecution.

27

EDWARD WAYNE EDWARDS

Edward Wayne Edwards (white, age 44) was a known serial killer from the late 1900’s.

He was known for five murders in Wisconsin and Ohio, two in 1977, two in 1980, and one in

1996. He was born in Akron, Ohio in 1933. Edwards grew up in an orphanage, where he was

both physically and mentally abused by the nuns that ran it (Cameron, 2014). At a young age, he

made his way into juvenile detention for his many enraged outbursts. He was allowed to leave

detention on the condition that he enlisted in the U.S. Marines (Andreadis, 2010). Soon after his

enlistment, he went AWOL and was dishonorably discharged. Succeeding his discharge, he

found himself traveling from state to state working odd jobs to support himself. Eventually, in

1955, he was sent to jail in Akron, where he escaped and continued to drift around the states

robbing gas stations. In 1961, Edwards made the FBI’s Most Wanted List (Cameron, 2014). He

wrote in his autobiography, that he never wanted to commit these crimes under a disguise

because he wanted to be famous (Edwards, 1972). Edwards was captured in 1962, and he was

imprisoned in Leavenworth. However, he was paroled in 1967, ten years before the killings

started (Sangiacomo, 2011).

His homicidal spree began in 1977. However, the murder focused on for this study is the

one of his foster son’s, Dannie Boy Edwards. Dannie (white, age 25) was killed in Burton, Ohio.

Dannie was a member of the U.S. Army and Edwards convinced him to go AWOL. When he

did, Edwards took him into the woods in Burton and shot him two times in the head (Andreadis,

2010). Investigators proved that he had planned the killing of his son for the $250,000 insurance

policy. Edwards had no apologies for the killing of his son and merely wanted to continue his

criminal behavior and avoid prison (Cameron, 2014).

28

Edwards confessed to the murder of five victims. But is has been argued that he may be

responsible for up to 15 plus homicides. In 2009, he was finally charged with first degree murder

for the death of Dannie. In 2011, he was sentenced to death in Louisville, Kentucky. Edwards

died on April 7, 2011, of natural causes, avoiding his ultimate execution in Columbus Ohio

(Sangiacomo, 2011).

Edwards' case was used for this study because after primary analysis it was concluded

that he had taken part in an insurance fraud scheme. However, after further review it was

discovered that Edwards actually met the definition of a serial killer. A serial killer is an

individual who repeatedly commits murder, typically with a distinct pattern in the selection of

victims, location, and method (Sutton, & Keatley, 2021). However, like the DeChant case, this

can be used to show a comparison between red-collar criminals and street-level criminals. Using

the characteristic patterns in Perri's RCM, Edwards' datum displayed the same characteristics as

Perri's original cases. During the primary analysis of his case, he was connected to an insurance

fraud scheme at the same time as the homicide of his foster son Dannie Edwards (Andreadis,

2010). Edwards displayed psychopathic tendencies shown in his homicidal spree through the late

70's. These tendencies were also displayed during his juvenile years when he grew up in a foster

home, and was sentenced to juvenile detention (Cameron, 2014).

Edwards took out a $250,000 insurance policy for his 25-year-old white adopted son,

Dannie Edwards. Afterwards, he took Danny into the woods in Burton, Ohio, and shot him twice

in the head (Andredis, 2010). Dannie's body was found in the woods by a hunter. It was only

later discovered by investigators that Edwards' motive was to collect the insurance money

(Edwards, 1972). Unlike Edwards, Dannie had no criminal record. There is no evidence in the

29

data that Dannie or Edwards had any debt problems. However, most of the data was collected

from Edwards' autobiography.

His autobiography provided evidence that supported many of the pattern characteristics

in Perri’s RCM. For example, it provides his age at the time if the homicide (44), his race

(white), and listed a series of odd jobs that he had throughout his life. He also mentioned his

previous criminal record which included robbery, assault, and homicide. Edwards made it very

clear that he did not want to wear a disguise because he wanted people to know it was him

committing the crime (Edwards, 1972). This response is evidence that he displayed narcissistic

tendencies with his high sense of self-esteem, and belief in superiority over others. This evidence

can also support the claim of his psychopathic characteristics as well.

In 2009, Edwards was convicted of first-degree murder for the homicide of Dannie

Edwards. In this trial, he also admitted to killing several others (Sangiacomo, 2011).

Investigators discovered blood and DNA evidence that linked Edwards to the crime. During his

trial, Edwards also admitted that he was motivated to kill Dannie to collect the money and get

away with murder (Andreadis, 2010). Similar to Perri’s findings, Edwards displayed

psychopathic traits. These traits included attitudes of manipulation, deception, and exploitation,

and their means always justify the ends, regardless of the crime. His case is important to this

study because it allows a comparison of street-level offenses (serial homicide) and red-collar

offenses (white-collar).

GARY W. PLOOF

Gary W. Ploof, (white, age 37) served as a staff sergeant in the U.S. Air Force in 2001.

He and his wife Heidi Ploof (white, age 29) were stationed at the Dover Air Force Base in

Delaware. Even though he was married, he was having an affair with a colleague of his. After the

30

affair started, the Air Force released news of a $100,000 life insurance benefit plan. Ploof found

himself to be automatically enrolled in this plan because he took no action to disenroll. Around

this time, Ploof was also making plans to move in with the woman he was having an affair with.

This event is when Ploof began to plan the homicide of his wife Heidi (Ploof v. State, 2008).

His plan was to kill Heidi as soon as the life policy took effect. He drove Heidi to a

Walmart parking lot and shot her in the head with a .357 magnum revolver. He had attempted to

make the murder look like a suicide with the placement of the gunshot. Ploof also developed a

plan to mislead the police by calling Heidi and gathering friends to help search for her as though

she were missing. Video footage shows Ploof quickly leaving the vehicle where Heidi was

found. He tried to hide the murder weapon on his property and asked friends to hold on to any

other pistols that he owned. Lastly, Ploof lied about knowing about the life insurance policy,

having a mistress, and the weapons he owned (Ploof v. State, 2008).

Ploof had shot his wife in the head in a Wal-Mart parking. Security videotape of the Wal-

Mart parking lot on the day that Heidi's body was found showed Ploof hurriedly walking away

from her vehicle (Bailey, 2013). Blood and DNA evidence confirmed it was Heidi. Heidi worked

at a grocery store and had no known debt problems. Neither Heidi nor Ploof had any previous

criminal records. Marital problems existed between Ploof and Heidi, which contributed to

Ploof’s extramarital affairs (Ploof v. State, 2008).

Ploof meets the definition of a red-collar criminal because he killed his wife to cover the

insurance fraud that he was committing (Ploof v. State, 2008). He committed homicide at the

same time as committing fraud. "Ploof revealed his cold-blooded nature after murdering Heidi,

by immediately carrying out an elaborate scheme to mislead the police and hide the

31

incriminating evidence, all while making inquiries concerning the life insurance. Although Ploof

expressed his remorse to the jury after the penalty hearing, he also feigned sadness while

attempting to mislead the police and his friends to believe that Heidi had committed suicide,"

Chief Justice Myron Steele said, writing for the court's majority (Ploof v. State, 2008, p.4).

The jury unanimously found Ploof guilty of first-degree murder. Evidence is shown

beyond a reasonable doubt that he killed his wife for pecuniary gain. An 11 to 1 vote found the

murder to be premeditated and a result of planning. (Ploof v. State, 2008). Ploof made several

incriminating statements when he told stories of his missing wife and then got caught in several

lies. For example, Ploof lied to the police about his ownership of several firearms, including the

murder weapon, and about his affair with another woman. He also falsely claimed that he was

not involved in the murder of his wife (Bailey, 2013). After Ploof admitted to the murder in his

testimony, he briefly spoke of the remorse he felt. However, this remorse was discounted by the

judge because he had faked remorse and distress to avoid detection after killing Heidi in the first

place (Ploof v. State, 2008). This idea suggests that he shares manipulative characteristics with

narcissistic and psychopathic traits. These represent similarities in Perri’s original case findings.

This case meets the description of red-collar crime because fraud was committed at the same

time the premeditated murder.

LINDA LOU CHARBONNEAU

Linda Lou Charbonneau (white, age 53) was convicted of killing her two husbands and

was sent to death row. Charbonneau was married to John Charbonneau (white, age 62) with

whom she had her third child. Her first husband and father of her first two children died in an

unfortunate car accident. Once she moved in with her second husband John, the two raised the

three children together. In 1997, Charbonneau grew tired of her relationship with John and left

32

him to marry his own nephew, Billy Sproates (white, age 45). After a few years with Sproates,

she returned to continue her relationship with John. She was still married to Sproates when she

returned to her second husband. Soon after her return to John, he was reported missing, and a

few weeks later, so was Sproates. The Delaware State Police began to investigate the two

disappearances. During the investigation, the police discovered Sproates body behind

Charbonneau and John’s home. For months, suspicion was settled on Charbonneau for the

disappearance of John as well. Eight months after Sproates body was discovered, Charbonneau,

her daughter Melissa, and her daughter’s boyfriend Willie Brown were arrested for the murder of

Sproates. After his arrest, Brown led investigators to John’s body as well (Murray, 2004).

The State of Delaware indicted the trio for the criminal offenses that arose out of John’s

and Sproates’ cases. Charbonneau had convinced her daughter and her daughter’s boyfriend to

kill the two men on her behalf. The two were merely part of her plan to secure the men’s

possessions and their money. The prosecution provided evidence in support of the plan to kill the

two men to collect their social security checks. The killing of Sproates was simply their way of

covering up John’s murder when Linda suspected that he was catching on to their murderous

dealings. Enough evidence was presented to the jury to land Charbonneau on death row. Linda

Lou Charbonneau was found guilty of two counts of first-degree murder. Owing to a

technicality, Linda's case was overturned. She was retried and re-sentenced to 20 years for only

John Charbonneau's murder (Charbonneau v. State of Delaware, 2004).

Charbonneau meets the definition of a red-collar crime because she was caught in a

Social Security and insurance fraud scam. She killed her husband Billy Sproates at the same time

as her fraudulent scheme against him and had her husband John Charbonneau killed after

defrauding him. Charbonneau had planned to collect her husband John for his social security

33

after having her daughter's boyfriend, Brown, bludgeon him in the head at their home and then

bury him to death in the woods outside Millsboro, Delaware (Charbonneau v. State of Delaware,

2004).

Investigators found John's blood on moving boxes, a shoe, and pieces of furniture found

in Charbonneau's possession (Murray, 2004). Charbonneau had created cover stories for herself

and her co-conspirators. Investigators visited her home in Bridgeville, Delaware to question her

about John's disappearance. She incriminated herself early on by claiming she had nothing to do

with him missing, she told them she was serving on jury duty on the date of his disappearance.

However, it was later discovered that there was no scheduled court for the 28th of September

when he was reported missing. This event is around the time she began to enter John's accounts

and withdraw any money he had in his accounts (Charbonneau v. State of Delaware, 2004).

Charbonneau moved out of the house she shared with John and moved in with Sproates

(Murray, 2004). Amongst her belongings were the bloody boxes that the investigators later

discovered in the testimony of witnesses. Sproates immediately questioned the bloody sight.

Linda followed his questioning with a threat "to be quiet or he would get the same thing as his

uncle" (Charbonneau v. State of Delaware, 2004, p. 7). This fact was a clear sign of her lack of

remorse and empathy towards the murder of her former husband John. This behavior coincides

with that of someone with narcissistic or psychopathic tendencies. Sproates showed these bloody

boxes to a friend, and former Maryland State Police officer, Roger Layton. Layton's experience

confirmed that the high-velocity blood spatter was consistent with that of a serious crime

(Charbonneau v. State of Delaware, 2004, p. 7).

Witnessing this blood evidence, Layton reached out to Detective Keith Marvel of the

Delaware State Police. Marvel was reassured that John was well enough, and the investigation

34

did not proceed. This event led to Charbonneau's arrangement of Sproates' death (Murray, 2004).

Like John before him, Charbonneau had a plan for Brown to kill Sproates. He was brutally

attacked with a knife and bludgeoning. Blood evidence revealed the horrific encounter. Sproates

autopsy uncovered that the violent attack is not what killed him, instead, he was buried alive

(Charbonneau v. State of Delaware, 2004). This is proof of overkill, if Sproates’ are left on the

ground he would eventually have succumbed to his injuries, but Brown accelerated the process

by depriving him of oxygen. Charbonneau meets all definitions of red-collar crime. She

committed fraudulent schemes prior to and at the same time as her homicides. She also meets

several behavioral characteristics as a narcissist and psychopath (lack of empathy, nor remorse,

manipulation, and deception). These traits were discovered across the cases in Perri’s original

red collar work. These similarities attest to the validity of the criminal profile.

LOUISE VERMILYEA

Louise Vermilyea (white, age 25) was a known American “Black Widow.” Her life and

murderous activities spanned through the 20th century. When she decided to murder outside of

her immediate family members suspicions arose. She killed a police officer named Arthur

Bissonette, the authorities were alerted and investigations into the deaths of her two husbands,

two known associates, and several family members began to ensue (The New York Times,

1911).

The murders began in 1893, near Barrington, Illinois. Here, Vermilyea took the life of her

first husband, Fred Brinkamp. His death was originally ruled as a heart attack. However, prior to

his death, Vermilyea made sure to have her named as his beneficiary to his $5,000 insurance

policy. Succeeding Brinkamp’s death, two of the six children, he had met similar fates (Cochran,

1912). Her stepdaughter 26-year-old Lilian Brinkamp grew suspicious of Vermilyea and soon

35

met a similar fate to her father’s. Because of the unusual number of deaths in this family, others

thought them to be cursed (The New York Times, 1911).

Soon after the death of her stepdaughter, Vermilyea remarried a man named Charles

Vermilyea. Three years after this marriage began Charles also died due to a sudden illness. From

this death, she collected $1,000 and a house in Crystal Lake, Illinois. In 1910, her stepson Frank

Brinkamp, from her first marriage died under the same circumstances as his father. On his

deathbed, he told others of his suspicion of his stepmother. As a result, Vermilyea received

$1,200 from his death. Her final kill was that of officer Bissonette, who died of arsenic

poisoning. Upon the discovery of the poisoning, Vermilyea was taken into custody by the

Chicago Police Department. It was then discovered that Bissonette’s father had named

Vermilyea as the beneficiary of his life insurance (The New York Times, 1911).

While Vermilyea ultimately was arraigned for the deaths of the lot, she was released on

$5,000 bail. This response was because there was a significant concern for her continued failing

health and exposure to the summer heat in a non-air-conditioned jail, pending her trial for the

poisonings. In April of 1915, a conference was held to determine the continuation of the trial. It

was decided that it would be impossible to obtain a conviction. It was assumed the trial would

cost too much without having the assurance of winning over a jury, for the prosecution ran into

the issue of finding jury members (only men were allowed then) that were willing to send a

woman to death row. It was decided that all charges would be dropped per the request of

Vermilyea’s attorney. It was estimated that she gained a total of around $15,000 from the nine

deaths (Chicago Tribune, 1912).

Vermilyea meets the definition of a red-collar criminal because she was caught on

multiple occasions for her insurance fraud scam. Specifically, she killed two of her stepchildren

36

for their suspicions of her involvement in her husband’s death. She used the same plan over and

over until ultimately, she was caught. She escaped prosecution due to her health and age by the

time authorities caught on to her plans. The red-collar definition is met because her murders

happened after or at the same time as her fraudulent schemes. Investigators merely caught onto

her criminal activity too late (The New York Times, 1911).

Her victims are as follows; Fred Brinkamp (white, age 24) killed for insurance fraud,

Cora Brinkamp (white, age 8), and Florence Brinkamp (white, age 4) killed so that she would not

get any money left by her father or be witnesses to the crime, Lillian Brinkamp (white, age 26)

killed for accusing Vermilyea of the murder of her father, Charles Vermilyea (white, age 59)

killed for insurance fraud, Harry Vermilyea (white, age n/a) killed for insurance fraud, Frank

Brinkamp (white, age 23) killed for insurance fraud, Arthur Bissonette (white, age 26) killed for

his suspicion of Vermilyea's homicidal spree. All of Vermilyea's murders were motivated by

financial gain in insurance fraud, or the desire to avoid detection and prosecution for such

homicidal acts (The New York Times, 1911).

Vermilyea incriminated herself by lying in an interview with Chicago Police Captain

Harding. When accused of her murders and asked how she felt about said accusations she

replied,

"They may go as far as they like, for I have nothing to fear. I have simply been

unfortunate in having people dying around me. My first husband was a farmer, and he

drank himself to death, though I feel ashamed to admit it. It was this way: He became

very careless and wouldn't look after things, and we moved into town and started a store.

Matters grew worse, and I decided the farm was best after all. Well, we moved back, and

37

apples were plentiful, and we made a lot of cider, and it was the hard cider that killed

him" (Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, 1911, p. 1).

This direct response supplies evidence of her narcissistic and psychopathic traits.

Vermilyea demonstrates a lack of empathy by referring to his death as unfortunate. She

continues by blaming her husband for his own death and insinuates he deserved it because he

"became very careless and wouldn't look after things." She also shows a lack of remorse for the

killings by pinning the blame on her victims (Lake County, Independent and Waukegan Weekly

Sun, 1911).

After the discovery of arsenic poisoning in her final victim, investigators linked the same

poisoning to her earlier victims as well. Vermilyea committed several red-collar crimes. She was

consistently committing insurance fraud, swindling, and acting under false pretenses. These are

all different forms of fraud as defined by the FBI (FBI, 2012). Owing to her lack of conviction,

she may be seen as a successful red-collar offender, meaning that she avoided detection and

prosecution. Similar to Perri’s original findings, Vermilyea did not display any known mental

disorders and held heavy narcissistic and psychopathic traits.

REV. JOHN DAVID TERRY

Reverend John David Terry (white, age 32) shot and killed church handyman James

Matheney (white, 32) on June 15, 1987. Before the death of Matheney, Terry had been

misappropriating church funds since early 1984. For example, he withdrew $10,000 to keep in

cash and another $5,000 to buy a motorcycle. Matheney soon became a part of a plan to assume

a new identity and stage his own death. Terry had discovered Matheney snooping around in the

church into things that may have exposed him. Matheney also met similar physical

characteristics to Terry, assisting in the plan to fake his death. Terry shot Matheney in the back

38

of the head with a .38 caliber pistol. Later, he cut the head and right arm off the victim, as well as

cut out any identifying tattoos from the skin to flush them down the toilet. This idea is how Terry

planned to stage the death with Matheney’s body (John David Terry v. State of Tennessee,

2001).

Terry removed the clothing from the rest of Matheney’s body and dressed it with his

own. Terry took the victim’s clothing, and the weapons used to dump them in a dumpster. After,

he purchased two five-gallon containers of gasoline and put them with the body in the church.

He used the motorcycle that he purchased to drive to a lake and dispose of the head and arm of

the victim. Terry then returned to the church, and he set it on fire to burn all evidence left behind.

Terry went on the run, paying for two nights at a motel in nearby Memphis. On June 18, 1987,

police apprehended Terry (John David Terry v. State of Tennessee, 2001).

Upon Terry’s arrest, a detective submitted to the record that Terry demonstrated a total

lack of emotion and remorse when he was being taken in. The arresting officer explained, “I

guess I was looking for some remorse or some signs. After being involved in a three-day

manhunt, like we had, I expected an awful lot more than what I saw. But I saw nothing but just

plain straight up–just no sign of emotion at all” (John David Terry v. State of Tennessee, 2001, p.

3).

Terry was tried for murder in the first degree and was convicted in 1988. He was

sentenced to die in the electric chair. This sentence was overturned on the account of an appeal

for improper instructions being given to the jury. However, once retried with another jury, they

too determined the sentence of death. In 2003, before his trial Terry hanged himself in the

bathroom of Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville (John David Terry v. State of

Tennessee, 2001). Though it may seem out of character for the reverend, because he had no

39

previous criminal record, Terry meets the definition of a red-collar criminal because he was

caught embezzling from the church that he had power over. He carried out his fraudulent scheme

before killing Matheney. He killed Matheney because he may have discovered the fraudulent

activity and Matheney’s body was also used in trying to avoid detection and prosecution. Terry

knew he was at the risk of being caught so he constructed a plan that would help him get away

with his actions (The New York Times, 1988).

Terry displayed similar characteristics to a narcissist and psychopath by manipulating

Matheney to fit the mold of his plan. He met Matheney and took the time to cultivate a

relationship as a result. After setting him up and killing him, Terry, dismembered the body and

threw it into a dumpster. This event supports the evidence of overkill (John David Terry v. State

of Tennessee, 2001). Investigators also discovered blood and DNA evidence at the crime scene at

the church. These characteristics are similar to the findings in Perri’s original study.

RESULTS

After a review of the cases, the data gathered supports Perri’s definition of red-collar crime. The

exploration of these cases determined that these killers did not merely have a lapse in judgment. In all the

cases determined to be red-collar, fraud had to occur before or at the same time as the homicide. 6 of the

100 cases sampled from the Murderpedia population were determined to contain white-collar crime

characteristics. However, only 4 of the 100 cases met the definition of a red-collar crime. In these 4 cases

(Ploof, Charbonneau, Vermilyea, and Terry), the killers committed homicide to avoid detection and

prosecution of their fraudulent activities.

Amy DeChant killed her boyfriend that was involved in fraudulent activity. Once Weinstein

caught onto her, she killed him to take anything he had left. This also aided in her evasion from the law