September 2019

Financial Alignment Initiative

South Carolina Healthy Connections Prime:

First Evaluation Report

Final

Prepared for

Sai Ma

Nancy Chiles Shaffer

Thomas Shaffer

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation

Mail Stop WB-06-05

7500 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, MD 21244-1850

Submitted by

Edith G. Walsh

RTI International

307 Waverly Oaks Road, Suite 101

Waltham, MA 02452-8413

RTI Project Number 0214448.001.007.000.000.006

[This page intentionally left blank.]

FINANCIAL ALIGNMENT INITIATIVE

SOUTH CAROLINA HEALTHY CONNECTIONS PRIME:

FIRST EVALUATION REPORT

By

RTI International

Catherine Ormond, MS

Matt Toth, MSW, PhD

Jennifer Howard, PhD

Lanre Adisa, BA

Emily Vreeland, MS

Ira Dave, MSPH

Yiyan Liu, PhD

Paul Moore, MA

Emily Gillen, PhD

Giuseppina Chiri, PhD

Wayne Anderson, PhD

Melissa Morley, PhD

Angela M. Greene, MS, MBA

Project Director: Edith G. Walsh, PhD

Federal Project Officers: Sai Ma, Nancy Chiles Shaffer, and Thomas Shaffer

RTI International

CMS Contract No. HHSM-500-2014-00037i TO#7

August 2019

This project was funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under contract no.

HHSM-500-2014-00037i TO #7. The statements contained in this report are solely those of the

authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services. RTI assumes responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the information

contained in this report.

_________________________________

RTI International is a registered trademark and a trade name of Research Triangle Institute.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the State officials who contributed information reflected in this

Evaluation Report through interviews during site visits and quarterly telephone calls. We also

thank the Medicare-Medicaid enrollees, managed care plan staff, consumer advocates, and other

stakeholders who also answered our questions about their experience and perspectives on the

demonstrations. We gratefully acknowledge the many contributions of CMS staff, especially our

Project Officers, Sai Ma, Nancy Chiles Shaffer, and Thomas Shaffer, and our former COR,

Daniel Lehman. We also thank other staff at RTI International, who helped to gather information

and produce tables for this report. Christopher Klotschkow, Michelle Bogus, Catherine Boykin,

and Roxanne Snaauw provided excellent editing and document preparation.

v

Contents

Section Page

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................ES-1

1. Overview .................................................................................................................................1

1.1 Evaluation Overview .....................................................................................................1

1.1.1 Purpose ...............................................................................................................1

1.1.2 What it Covers ...................................................................................................1

1.1.3 Data Sources ......................................................................................................2

1.2 Model Description and Demonstration Goals ................................................................4

1.3 Changes in Demonstration Design.................................................................................6

1.4 Overview of State Context .............................................................................................7

2. Integration of Medicare and Medicaid ..................................................................................11

2.1 Joint Management of Demonstration ...........................................................................11

2.2 Overview of Integrated Delivery System ....................................................................12

2.2.1 Healthy Connections Prime Plans ....................................................................12

2.2.2 Provider Arrangements and Services ...............................................................12

2.2.3 Training and Support for Plans and Providers .................................................15

2.3 Major Areas of Integration...........................................................................................16

3. Eligibility and Enrollment.....................................................................................................17

3.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................17

3.2 Enrollment Process ......................................................................................................17

3.2.1 Eligibility .........................................................................................................17

3.2.2 Phases of Enrollment .......................................................................................18

3.2.3 Passive Enrollment Experience ........................................................................20

3.2.4 Integration of Medicare and Medicaid Enrollment Systems ...........................21

3.2.5 Contacting and Locating Enrollees ..................................................................21

3.3 Summary Data .............................................................................................................22

4. Care Coordination .................................................................................................................25

4.1 Care Coordination Model ............................................................................................25

4.1.1 Assessment .......................................................................................................26

4.1.2 HCBS Waiver Services and Coordination .......................................................29

4.1.3 Care Planning Process......................................................................................30

4.2 Information Exchange ..................................................................................................33

5. Beneficiary Experience .........................................................................................................35

5.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................35

5.2 Impact of the Demonstration on Beneficiaries ............................................................36

5.2.1 Overall Satisfaction with Healthy Connections Prime ....................................36

5.2.2 New or Expanded Benefits ..............................................................................38

5.2.3 Medical and Specialty Services .......................................................................39

5.2.4 Care Coordination Services .............................................................................40

vi

5.2.5 Beneficiary Access to Care and Quality of Services .......................................41

5.2.6 Person-centered Care and Patient Engagement ...............................................43

5.2.7 Personal Health Outcomes and Quality of Life ...............................................43

5.2.8 Experience of Special Populations...................................................................44

5.2.9 Beneficiary Protections ....................................................................................45

6. Stakeholder Engagement ......................................................................................................49

6.1 Overview ......................................................................................................................49

6.2 Organization and Support ............................................................................................50

6.2.1 Stakeholder Council .........................................................................................50

7. Financing and Payment .........................................................................................................53

7.1 Rate Methodology ........................................................................................................53

7.1.1 Rating Categories and Risk Adjustments ........................................................53

7.1.2 Savings Percentage ..........................................................................................54

7.1.3 Performance Incentives ....................................................................................55

7.1.4 Medical Loss Ratio ..........................................................................................56

7.2 Financial Impact...........................................................................................................56

7.2.1 Early Implementation Experience....................................................................56

7.2.2 Rate Methodology Design Implications ..........................................................57

7.2.3 Cost Experience ...............................................................................................58

8. Service Utilization ................................................................................................................61

8.1 Overview of Benefits and Services ..............................................................................62

8.2 Impact Analyses on the Demonstration Eligible Population .......................................63

8.2.1 Descriptive Statistics on the Demonstration Eligible Population ....................71

8.2.2 Impact Analyses on the Demonstration Eligible Population with SPMI .........71

8.2.3 Service Use for Enrollee and Non-Enrollee Populations in South

Carolina ............................................................................................................73

8.2.4 Service Use by Demographic Characteristics of Eligible Beneficiaries ..........74

9. Quality of Care ......................................................................................................................79

9.1 Quality Measures .........................................................................................................79

9.2 Quality Management Structures and Activities ...........................................................81

9.2.1 State and CMS Quality Management Structures and Activities ......................82

9.2.2 Healthy Connections Prime MMP Quality Management Structure and

Activities ..........................................................................................................82

9.2.3 Independent Quality Management Structures and Activities ..........................83

9.3 Results for Selected Quality Measures ........................................................................83

9.3.1 HEDIS Quality Measures Reported for Healthy Connections Prime

Plans .................................................................................................................83

10. Cost Savings Calculation ......................................................................................................87

10.1 Evaluation Design ........................................................................................................88

10.2 Medicare Expenditures: Constructing the Dependent Variable ...................................90

10.3 Results ..........................................................................................................................93

10.3.1 Regression Analysis .........................................................................................95

vii

10.4 Discussion ....................................................................................................................98

11. Conclusions ...........................................................................................................................99

11.1 Implementation-related Successes, Challenges, and Lessons Learned .......................99

11.2 Demonstration Impact on Service Utilization and Costs ...........................................100

11.3 Next Steps ..................................................................................................................101

References ....................................................................................................................................R-1

Appendices

A Comparison Group Methodology for South Carolina Demonstration Year 1 ................... A-1

B Analysis Methodology ........................................................................................................B-1

C Descriptive Tables ..............................................................................................................C-1

D Sensitivity Analysis Tables ................................................................................................ D-1

E Summary of Predemonstration and Demonstration Design Features for Medicare

and Medicaid Beneficiaries in South Carolina ................................................................... E-1

viii

List of Tables

Number Page

1 Healthy Connections Prime MMP profiles .......................................................................... 13

2 Transition of HCBS waiver functions from State to MMP ................................................. 14

3 Healthy Connections Prime enrollment phases ................................................................... 19

4 Percentage of members that Healthy Connections Prime plans were unable to reach

following three attempts, within 90 days of enrollment, by quarter .................................... 22

5 Key events affecting enrollment and percentage enrolled in Healthy Connections

Prime .................................................................................................................................... 23

6 Total percentage of enrollees whose assessment was complete within 90 days of

enrollment ............................................................................................................................ 28

7 Members with care plans within 90 days of enrollment ...................................................... 32

8 Care coordination staffing ................................................................................................... 33

9 Beneficiary overall satisfaction, 2017 ................................................................................. 37

10 Care coordination, 2017 ....................................................................................................... 41

11 Rate cell Medicaid payments per member per month, demonstration year 1 and

demonstration year 2 ............................................................................................................ 54

12 Savings percentages by demonstration year ........................................................................ 55

13 Average, minimum, and maximum HCC score by MMP during demonstration year

1 (February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016) ........................................................................... 59

14 Summary of South Carolina demonstration impact estimates for demonstration

period (February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016) ................................................................... 62

15 Adjusted means and impact estimate for eligible beneficiaries in the demonstration

and comparison groups in South Carolina through December 31, 2016 ............................. 66

16 Adjusted means and impact estimate for eligible beneficiaries in the demonstration

and comparison groups in South Carolina through the demonstration period

February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016................................................................................. 70

17 Selected HEDIS measures for Healthy Connections Prime plans, 2016 ............................. 84

18 Data sources for monthly Medicare expenditures ............................................................... 90

19 Adjustments to Medicare expenditures variable .................................................................. 91

20 Mean monthly Medicare expenditures for Healthy Connections Prime eligibles and

comparison group, predemonstration period and demonstration period 1,

unweighted ........................................................................................................................... 95

21 Mean monthly Medicare expenditures for Healthy Connections Prime eligibles and

comparison group, predemonstration period and demonstration period 1, weighted .......... 95

22 Demonstration effects on Medicare savings for eligible beneficiaries—Difference-

in-difference regression results, Healthy Connections Prime eligibles and

comparison group ................................................................................................................ 96

23 Adjusted means and overall impact estimate for eligible beneficiaries in the

demonstration and comparison groups, Healthy Connections Prime eligibles and

comparison group ................................................................................................................ 97

ix

List of Figures

Number Page

1 Demonstration effects on service utilization for eligible beneficiaries in South

Carolina—Difference-in-differences regression results for the demonstration

period, February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016 .................................................................... 64

2 Demonstration effects on long-stay nursing facility use for eligible beneficiaries in

South Carolina—Difference-in-differences regression results for the demonstration

period, February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016 .................................................................... 64

3 Demonstration effects on RTI quality of care measures for eligible beneficiaries in

South Carolina—Difference-in-differences regression results for the demonstration

period, February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016 .................................................................... 68

4 Demonstration effects on service utilization for eligible beneficiaries with SPMI in

South Carolina—Difference-in-differences regression results for the demonstration

period, February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016 .................................................................... 72

5 Demonstration effects on quality of care and care coordination for eligible

beneficiaries with SPMI in South Carolina—Difference-in-differences regression

results for the demonstration period, February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016 ..................... 73

6 Percent with use of selected Medicare services ................................................................... 75

7 Service use among all demonstration eligible beneficiaries with use of service per

1,000 user months ................................................................................................................ 76

8 Service use among all demonstration eligible beneficiaries per 1,000 eligible

months .................................................................................................................................. 77

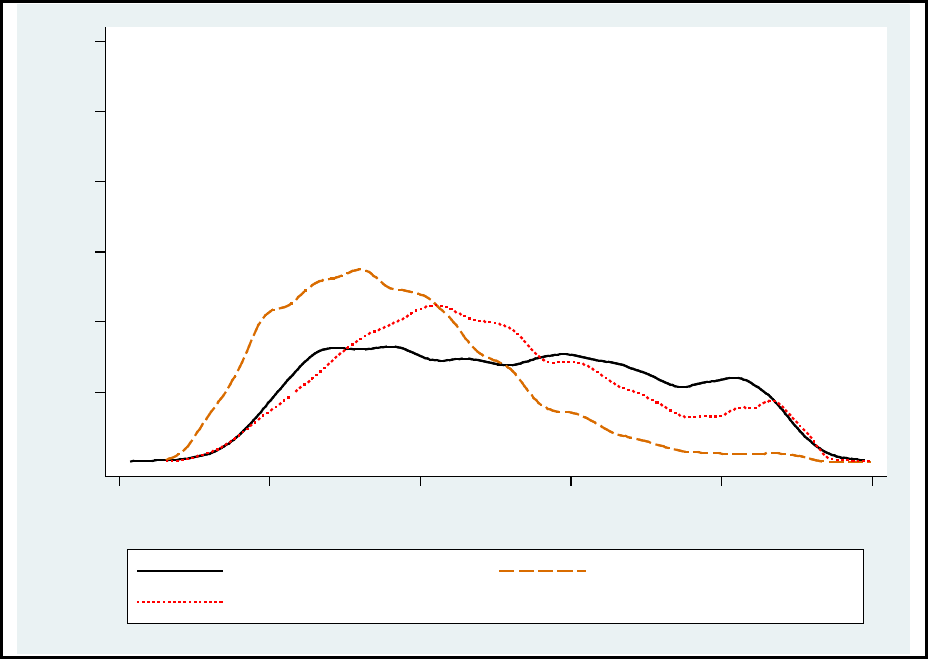

9 Mean monthly Medicare expenditures, predemonstration and demonstration period,

Healthy Connections Prime eligible and comparison group, February 2013–

December 2016 .................................................................................................................... 93

10 Mean monthly Medicare expenditures (weighted), predemonstration and

demonstration period, Healthy Connections Prime eligibles and comparison group,

February 2013–December 2016........................................................................................... 94

x

[This page intentionally left blank.]

xi

Glossary of Terms

ACL Administration for Community Living

ACSC Ambulatory care sensitive condition

ADL Activities of daily living

CAHPS Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

CICO Coordinated and Integrated Care Organizations

CLTC Community Long Term Care (SCDHHS’s division previously responsible

for HCBS services for demonstration enrollees)

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

CMT Contract Management Team

CTM Complaint Tracking Module

DinD Difference-in-Difference

DMH South Carolina’s Department of Mental Health

D-SNP Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan

EQRO External Quality Review Organization. For Healthy Connections Prime, it

is the Carolinas Center for Medical Excellence (CCME).

FFS Fee-for-service

HCBS Home and community-based services

HCC Hierarchical Condition Category

HEDIS Health Effectiveness Information and Data Set

HOS Health Outcomes Survey

HRA Health risk assessment

IC Implementation Council

ICP Individual care plan

IRE Medicare Independent Review Entity

LIS Low income subsidy

xii

LTC Long term care

LTSS Long-term services and supports

MA Medicare Advantage

MARx Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug System

MAXIMUS the enrollment broker for Healthy Connections Prime

MCO Managed care organization

MDS Minimum Data Set

MFFS Managed fee-for-service

MFP Money Follows the Person

MLR Medical loss ratio

MMCO Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office

MMP Medicare-Medicaid Plan. In South Carolina, the MMPs are Absolute Total

Care (Centene), Advicare Advocate (through August 2016), Molina

Healthcare, and First Choice VIP Care Plus by Select Health of South

Carolina.

MOU Memorandum of Understanding

MT Multidisciplinary team, also known as Interdisciplinary Care Team

OSA Office for the Study of Aging at the University of South Carolina

NF Nursing facility

PACE Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly

PCP Primary care physician or provider

Phoenix SCDHHS’ electronic Medicaid HCBS waiver case management system

PMPM per member per month

POC Plan of care

Prime Advocate Healthy Connections Prime’s ombudsman, who is also the LTC

Ombudsman for the State.

SCDHHS South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services

xiii

SDRS State Data Reporting System

SHIP State health insurance program

SPA State Plan Amendment

SPMI Serious and persistent mental illness

Waiver-like services Flexible benefits that MMPs may provide to Healthy Connections Prime

enrollees. They are often used prior to enrollment into an HCBS waiver.

xiv

[This page intentionally left blank.]

ES-1

Executive Summary

The Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office and the Innovation Center at the Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have created the Medicare-Medicaid Financial Alignment

Initiative to test, in partnerships with States, integrated care models for Medicare-Medicaid

enrollees. CMS contracted with RTI International to monitor the implementation of the

demonstrations and to evaluate their impact on beneficiary experience, quality, utilization, and

cost. The evaluation will include a final aggregate evaluation report and individual State-specific

evaluation reports.

South Carolina and CMS launched the Healthy Connections Prime demonstration in

February 2015 to integrate care for Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries throughout the State. Four

health plans were competitively selected to operate Medicare-Medicaid Plans (MMPs). MMPs

receive capitated payments from CMS and the State to finance all Medicare and Medicaid

services. MMPs also provide care coordination, a new palliative care benefit, and flexible

benefits.

Beneficiaries who are 65 years or older and living in the community are eligible for the

demonstration, which operated in 39 of the 46 counties in the State as of December 2017.

Participants in three home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver groups are also

eligible to participate.

This First Evaluation Report for the South Carolina demonstration describes

implementation of the Healthy Connections Prime demonstration and early analysis of the

demonstration’s impacts. The report includes findings from qualitative data for February 1, 2015

through December 31, 2017, with key qualitative information through mid-2018, and

quantitative results from February 1, 2015 through December 31, 2016. Data sources include key

informant interviews, beneficiary focus groups, the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare

Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey results, Medicare claims data, the Minimum Data Set

nursing facility assessments, MMP encounter data, and other demonstration data. Future analyses

also will include Medicaid claims and encounters as those data become available.

Highlights

Eligibility and Enrollment

• In December 2017, approximately 20,726 beneficiaries were eligible for the

demonstration and 11,511 beneficiaries were enrolled. Beneficiaries eligible for

passive enrollment into the demonstration included Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries

who received their Medicare benefits under fee-for-service. Medicare-Medicaid

beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage could also choose to disenroll from

their Medicare Advantage plan and opt into the demonstration.

• Initially in 2013, MMPs developed financial plans, built infrastructure, and hired staff

to support Healthy Connections Prime based on the State’s estimate of 53,000 eligible

beneficiaries, which included beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans

who were ineligible for passive enrollment. By 2016 and 2017, although MMPs had

ES-2

streamlined staffing and support for the demonstration, two of the three plans cited

financial concerns in sustaining their participation in the demonstration, due to lower

than expected enrollment and higher than expected costs.

• The demonstration experienced delays and pauses in passive enrollment due to

legislative actions at the start, and subsequently while the State’s leadership

considered including the demonstration population in a new managed long-term

services and supports (MLTSS) program. These delays resulted in a lack of

momentum to build enrollment and, consequently, a concern by MMPs and

stakeholders about the viability and future of the demonstration.

• In July 2018, CMS, the State, and all three plans agreed to extend the demonstration

through December 2020. The agreement included a plan to increase the eligible pool

by introducing passive enrollment to Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan (D-SNPs)

enrollees. It also reduced the savings percentages applied to the capitated rates that

CMS and the State pay to the plans effective 2018 and eliminated some

administrative requirements of the plans.

Care Coordination

• Evaluation of social determinants of health is an important factor in the

demonstration’s home-based enrollee assessments along with the beneficiary’s

mental, cognitive, and physical health. Care coordinators connect enrollees with

community-based groups to provide services that can enable enrollees to live safely in

their homes in this very rural State. Plans provide varying degrees of additional

flexible benefits primarily focused on nursing facility diversion.

Beneficiary Experience

• 2017 CAHPS survey results show that 54 to 66 percent of enrollees rated their

satisfaction with the three plans as a 9 or 10 (with 10 being the highest). Similarly,

almost all RTI focus group participants in South Carolina rated their plans a 9 or 10.

• 2016 and 2017 focus group participants were consistent in stating that the lack of

copays was the most important factor to improved access to care and quality of life.

Many noted that the funds not spent on copays were now used for food and other

essential items. Others noted that they were no longer turned away at providers’

offices for not having sufficient funds to receive care.

• Participants in focus groups generally knew their care coordinator by name and

described their reliance on their services. Focus group participants described ways in

which some care coordinators took extraordinary measures to accompany members to

appointments to ensure they received needed care.

• The volume of complaints and appeals has remained low throughout the

demonstration. The State’s long-term care ombudsman serves as the demonstration’s

Prime Advocate or ombudsman. In addition to working with plans to resolve disputes,

ES-3

she participates in the contract management team, and provides outreach to potential

enrollees. Plans reported the Prime Advocate is a major demonstration asset.

• Among those individuals who disenrolled from Healthy Connections Prime, surveys

and member exit interviews showed beneficiary preference to stay with their current

providers who were not in the MMPs’ networks. MMPs experienced some difficulty

attracting a wide provider network due, in part, to fear of managed care, and the

reluctance of some established health care networks to participate in the

demonstration.

Service Utilization

• As measured across all eligible beneficiaries, the demonstration resulted in a 19.0

percent reduction in the probability of inpatient admissions, a 16.9 percent reduction

in the probability of skilled nursing facility admission, an 18.5 percent reduction in

the probability of overall ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC) admissions,

and a 19.8 percent reduction in the probability of chronic ACSC admissions (see

Table ES-1). Conversely, the demonstration resulted in a 27.2 percent increase in the

probability of any new long-stay nursing facility use.

1

These reported changes, which

although appear large in percentage terms in comparison to the comparison group, are

actually quite small in absolute terms, reflecting usually less than a one percentage

point change in the probability of service use. Section 8 on service utilization and

Appendix B contain an explanation of the research design and populations analyzed.

• Results for those with serious and persistent mental illness on the probability of

inpatient or skilled nursing facility admission or ER visits were in the same direction

and to a similar degree as those for all eligible beneficiaries, as well as for the number

of evaluation and management visits.

1

This finding should be interpreted with caution as State-level eligibility determination delays for long-stay

nursing facility approval could have contributed to this finding. During the period covered by this report, long-

stay nursing facility residents were excluded from being eligible to enroll into the demonstration. However, due

to delays in determining nursing facility eligibility, individuals newly requiring long-stay nursing facility

services were enrolled in the demonstration, thus raising the probability of a long-stay nursing facility stay in the

demonstration group. Potentially, if beneficiaries with those long-stay nursing facility stays had been more

quickly identified, they would have been ineligible for demonstration enrollment.

ES-4

Table ES-1

Summary of South Carolina demonstration impact estimates for demonstration period

(February 1, 2015–December 31, 2016)

(p < 0.1 significance level)

Measure

All demonstration eligible

beneficiaries

Demonstration eligible

beneficiaries with SPMI

Probability of inpatient admission Decreased Decreased

Probability of ambulatory care

sensitive condition (ACSC)

admissions, overall

Decreased NS

Probability of ACSC admissions,

chronic

Decreased NS

All-cause 30-day readmissions NS Decreased

Probability of emergency room (ER)

visit

Decreased Decreased

Preventable ER visits Decreased NS

30-day follow-up after mental health

discharges

NS NS

Probability of skilled nursing facility

(SNF) admission

Decreased Decreased

Probability of any new long-stay

nursing facility (NF) use

Increased N/A

Physician evaluation and

management (E&M) visits

Decreased Decreased

N/A = not applicable; NS = not statistically significant; SPMI = serious and persistent mental illness.

SOURCE: RTI analysis of Medicare and Minimum Data Set data.

Cost Savings

• The results of preliminary Medicare cost savings analyses using a difference-in-

differences regression approach do not indicate savings or losses due to the South

Carolina demonstration over the period February 2015–December 2016. The cost

savings analyses do not include Medicaid data due to current data unavailability, but

these data will be incorporated into future calculations as they become available.

1

1. Overview

1.1 Evaluation Overview

1.1.1

Purpose

The Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office (MMCO) and the Innovation Center at the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have created the Medicare-Medicaid

Financial Alignment Initiative to test, in partnerships with States, integrated care models for

Medicare-Medicaid enrollees. The goal of these demonstrations is to develop person-centered

care delivery models integrating the full range of medical, behavioral health, and long-term

services and supports (LTSS) for Medicare-Medicaid enrollees, with the expectation that

integrated delivery models would address the current challenges associated with the lack of

coordination of Medicare and Medicaid benefits, financing, and incentives.

This report on the South Carolina capitated model demonstration under the Medicare-

Medicaid Financial Alignment Initiative, called Healthy Connections Prime, is one of several

reports that will be prepared over the next several years to evaluate the demonstration. CMS

contracted with RTI International to monitor the implementation of the demonstrations under the

Financial Alignment Initiative and to evaluate their impact on beneficiary experience, quality,

utilization, and cost. The evaluation includes a final aggregate evaluation (Walsh et al., 2013)

and individual State-specific evaluation reports.

The goals of the evaluation are to monitor demonstration implementation, evaluate the

impact of the demonstration on the beneficiary experience, monitor unintended consequences,

and monitor and evaluate the demonstration’s impact on a range of outcomes for the eligible

population as a whole and for special populations (e.g., people with mental illness and/or

substance use disorders, LTSS recipients). To achieve these goals, RTI collects qualitative and

quantitative data from South Carolina each quarter; analyzes Medicare and Medicaid enrollment,

claims, and encounter data; conducts site visits, beneficiary focus groups, and key informant

interviews; and incorporates relevant findings from any beneficiary surveys conducted by other

entities. In addition to this report, monitoring and evaluation activities will also be reported in

subsequent evaluation reports.

1.1.2

What it Covers

This report analyzes implementation of the Healthy Connections Prime demonstration

from its initiation on February 1, 2015 through December 31, 2017. For this reporting period,

quantitative data based on Medicare claims and encounter data and the nursing facility Minimum

Data Set 3.0 through 2016 are included. To capture relevant information generated at the

conclusion of the demonstration period or immediately afterward, this report also includes key

updated qualitative information through mid-2018. It describes the South Carolina Healthy

Connections Prime demonstration key design features; examines the extent to which the

demonstration was implemented as planned; identifies any modifications to the design; and

discusses the challenges, successes, and unintended consequences encountered during the period

covered by this report. It also includes data on the beneficiaries eligible and enrolled, geographic

areas covered, and status of the participating Medicare-Medicaid Plans (hereafter referred to as

2

Healthy Connections Prime plans or MMPs). Finally, the report includes data on care

coordination, the beneficiary experience, stakeholder engagement activities, and, to the extent

that data are available, analyses of utilization and quality, and a summary of preliminary findings

related to Medicare savings results in the first demonstration year.

1.1.3

Data Sources

A wide variety of information informed this First Evaluation Report of the Healthy

Connections Prime demonstration. Data sources used to prepare this report include the

following:

Key informant interviews. The RTI evaluation team conducted in-person site visits in

South Carolina in July 2015 and July 2016 and conducted in-depth telephone interviews in

October and November 2017. The team interviewed the following types of individuals: State

policy makers and the South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (SCDHHS)

staff, CMS and State contract management team (CMT) members, Ombudsman Program

officials, MMP officials, MMP care coordinators, hospital and nursing facility providers,

advocates and other stakeholders.

Focus groups. The RTI evaluation team conducted eight focus groups in South Carolina

in 2016 and six in 2017. A total of 64 enrollees and 14 proxies participated in the RTI focus

groups. Participants were assigned to groups based on their LTSS and behavioral health services

use, race, ethnicity, and primary language. Focus groups were not conducted with beneficiaries

who opted out of the demonstration or who disenrolled.

Surveys. Medicare requires all Medicare Advantage plans, including Healthy

Connections Prime plans, to conduct an annual assessment of the experiences of beneficiaries

using the Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug CAHPS survey instrument. The survey was not

conducted in 2015 or 2016 due to low enrollment in the demonstration during those years. The

2017 survey for Healthy Connections Prime was conducted in the first half of 2017 and included

the core Medicare CAHPS questions and 10 supplemental questions added by the RTI evaluation

team. Survey results for a subset of 2017 survey questions are incorporated into this report.

Findings are available at the Healthy Connections Prime plan level only. The frequency count for

some survey questions may be suppressed because too few enrollees responded to the question.

Comparisons with findings from all Medicare Advantage plans are available for core CAHPS

survey questions but not for the RTI supplemental questions.

Demonstration data. The RTI evaluation team reviewed data provided quarterly by

South Carolina through the State Data Reporting System (SDRS). These data included eligibility,

enrollment, and information reported by South Carolina on its stakeholder engagement process,

accomplishments on the integration of services and systems, any changes made in policies and

procedures, and a summary of successes and challenges. This report also uses data for quality

measures reported by Healthy Connections Prime plans and submitted to CMS’ implementation

3

contractor, NORC.

2,3

Data reported to NORC include core quality measures that all Medicare-

Medicaid Plans are required to report, as well as State-specific measures that Healthy

Connections Prime plans are required to report. Due to some reporting inconsistencies across

plans in 2015, plans occasionally resubmit data for prior demonstration years; therefore, these

data are considered preliminary.

Demonstration policies, contracts, and other materials. This report uses several data

sources, including the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the State and Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and State of

South Carolina, 2013; hereafter, MOU, 2013); the three-way contract (U.S. Department of

Health & Human Services and the South Carolina Department of Health & Human Services,

2014; hereafter, South Carolina three-way contract, 2014); the Summary of Contract Changes

dated November 1, 2017, contract amendments dated July 1, 2018, and materials available on the

CMS website: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-

Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-

Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/SouthCarolina.html; documents available on the Healthy

Connections Prime website: https://msp.scdhhs.gov/SCDue2/site-page/trainings-and-

presentations; data reported through the State Data Reporting System [RTI, SDRS]), and

documents on the CMS Medicare-Medicaid Coordination website (Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services, 2018).

Conversations with CMS and SCDHHS officials. To monitor demonstration progress,

the RTI evaluation team engages in periodic phone conversations with SCDHHS and CMS.

These might include discussions about new policy clarifications designed to improve plan

performance, quality improvement activities, and contract management team actions.

Complaints and appeals data. Complaint (also referred to as grievance) data are from

three separate sources: (1) complaints from beneficiaries reported by Healthy Connections Prime

plans to SCDHHS, and separately to CMS’ implementation contractor, NORC; (2) complaints

received by SCDHHS or 1-800-Medicare and entered into the CMS electronic Complaint

Tracking Module (CTM);

4

and (3) qualitative data obtained by RTI on complaints. Appeals data

are based on data reported by MMPs to SCDHHS and NORC, for Core Measure 4.2, and the

Medicare Independent Review Entity (IRE). Data on critical incidents and abuse reported to

SCDHHS and CMS’ implementation contractor by Healthy Connections Prime plans are also

included in this report.

Although a discussion of the South Carolina MMPs is included, this report presents

information primarily at the Healthy Connections Prime demonstration level. It is not intended to

2

Data are reported for February 2015 through December 2017.

3

The technical specifications for reporting requirements are in the Medicare-Medicaid Capitated Financial

Alignment Model Core Reporting Requirements document, which is available at

https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-

Medicaid-Coordination-Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/MMPInformationandGuidance/MMP

ReportingRequirements.html.

4

Data are presented for the time period February 2015 through December 2017.

4

assess individual plan performance, but individual plan information is provided where plan level

data are the only data available, or where plan level data provide additional context.

Service utilization data. Evaluation Report analyses used data from many sources. First,

the State provided quarterly finder files containing identifying information on all demonstration

eligible beneficiaries in the demonstration period. Second, RTI obtained administrative data on

beneficiary demographic, enrollment, and service use characteristics from CMS data systems for

both demonstration and comparison group members. Third, these administrative data were

merged with Medicare claims and encounter data, as well as the Minimum Data Set.

Although Medicaid service data on use of LTSS, behavioral health, and other Medicaid-

reimbursed services were not available for the demonstration period and therefore are not

included in this report, CMS administrative data identifying eligible beneficiaries with serious

and persistent mental illness (SPMI) was available, so that their Medicare service use could be

presented in this report. Future reports will include findings on Medicaid service use once data

are available.

1.2 Model Description and Demonstration Goals

The goals of Healthy Connections Prime are to alleviate fragmentation and improve

coordination of services for Medicare-Medicaid enrollees, enhance quality of care, and reduce

costs for both the State and the Federal government. This demonstration aims to improve the

entire beneficiary care experience by engaging beneficiaries in their care and ensuring that they

have the choice to self-direct services as appropriate. Improving the beneficiary experience can

lead to system-wide benefits such as better quality, improved transitions between care settings,

fewer health disparities, reduced costs for payers, and the elimination of cost shifting between

Medicare and Medicaid (MOU, 2013, p. 3). Healthy Connections Prime plans are responsible for

delivery and coordination of all medical, behavioral health, and LTSS for their enrollees, as well

as providing care coordination and the new palliative care benefit.

Period of demonstration. Healthy Connections Prime began on February 1, 2015 and

was due to expire on December 31, 2018. In July 2018, CMS, the State, and all three MMPs

agreed to extend the demonstration until December 31, 2020 (CMS, 2018a).

Financial model. Healthy Connections Prime plans are paid a blended, risk-adjusted

capitated rate covering all Medicare and Medicaid services. Medicare Parts A and B and

Medicaid payments reflect the application of savings percentages and quality withholds (see

Section 7.1, Rate Methodology).

Eligible population. Beneficiaries with full benefit Medicare and Medicaid and who are

age 65 or over and living in the community at the time of enrollment, are eligible for the

demonstration. This had been a population of special interest to the State which had reduced its

nursing facility admissions by increasing home and community-based services (HCBS). Except

for the State’s Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) that only covered four of

the State’s 46 counties, there had been no previous effort to integrate HCBS with primary care

and behavioral health services. The demonstration provided this opportunity.

5

Beneficiaries participating in the Community Choices, HIV/AIDS, or Mechanical

Ventilation Dependent waiver programs for HCBS are eligible for the demonstration. Individuals

who transition from a nursing facility into the community, and are otherwise eligible, may elect

to enroll in the demonstration. Individuals already enrolled who later enter a nursing facility may

remain in the demonstration (MOU, 2013, p. 10). Any Healthy Connections Prime enrollee

residing in a nursing facility for more than 90 days before transition from that facility also may

qualify for the State’s Money Follows the Person Rebalancing demonstration, called Home

Again. Upon transition, enrollees must enter one of the three participating waivers included in

Healthy Connections Prime. Once Healthy Connections Prime enrollees return to the

community, the MMP must offer them any enhanced HCBS covered through the Home Again

program (South Carolina three-way contract, 2014, p. 97).

Healthy Connections Prime plans. SCDHHS and CMS initially contracted with four

plans, originally known as Coordinated and Integrated Care Organizations (CICOs), Absolute

Total Care (Centene), Advicare Advocate, Molina Healthcare, and First Choice VIP Care Plus by

Select Health of South Carolina. In early 2016, after State-contracted testing showed that

beneficiaries preferred the name Medicare-Medicaid Plan (MMP), the CICO name was rarely

used. Advicare’s managed care product was purchased by WellCare Health Plans, Inc., and

withdrew from the demonstration effective August 31, 2016, leaving three MMPs in the

demonstration.

Geographic coverage. Initially, the demonstration operated in 41 of the State’s 46

counties. After Advicare’s departure, 39 of the 46 counties were covered by at least one of the

three remaining MMPs. At the end of 2017, the three MMPs each covered from 29 to 39 of the

46 counties. MMPs were unable to contract with sufficient numbers of providers in seven

counties in this very rural State; therefore, those counties are not included in the demonstration.

Beneficiaries in the counties with one MMP may opt into the demonstration, but, during the

period of this report, may not be passively enrolled. In July 2018, the State made the decision to

allow eligible beneficiaries in counties in which one plan operates to be passively enrolled into

that plan beginning fall 2018.

Care coordination. Care coordination is a central feature of the South Carolina

demonstration and plans are required to provide care coordination services to all enrollees. It

begins with a home visit and comprehensive assessment, followed by the development of a care

plan. A multidisciplinary team, dependent upon the needs and wishes of the enrollee and led by a

care coordinator, delivers care coordination to all enrollees (see Section 4.1, Care Coordination

Model).

Benefits. The demonstration provides coordination of primary care, acute care,

behavioral health services, and LTSS, and a new palliative care benefit. Beneficiaries enrolled in

the HCBS waivers receive their coordinated waiver benefits under the demonstration.

Enrollees who have a history of hospitalization or emergency department use due to pain

or symptom management and who have been diagnosed with certain conditions, such as cancer,

end-stage renal disease, or congestive heart failure, may receive the new palliative care benefit. It

is designed to improve the enrollee’s quality of life by providing pain management together with

curative treatment and, according to the State, by “adding an extra layer of support to the

6

enrollee.” The State has engaged various organizations to assist in developing education for

providers and plans and adopted use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Charlson, n.d.). Fine-

tuning the reporting specifications and tracking services has been particularly challenging in

providing this benefit according to both State officials and plans. By the end of 2017, the

demonstration was focused on the following activities: determining evidence of increase in

member advance care planning; tracking members from palliative care to hospice; and assessing

pre and post palliative care costs (SCDHHS, 2017). For more on this topic, see Section 5,

Beneficiary Experience).

Supplemental benefits and waiver-like services. Plans have supplemental benefits

available to members enrolled in their Healthy Connections Prime products that vary by plan.

Examples of such benefits include gym memberships, coverage of eyewear expense (e.g., $150

every 2 years), and a monthly allowance for over-the-counter drug products. At their discretion,

plans may also provide flexible benefits, known in South Carolina as “waiver-like” services to

enable enrollees to postpone institutionalization or prevent higher levels of care for frail

beneficiaries. These benefits typically include home modifications, respite, personal care or other

services and are provided to members who do not meet the level of care requirements to

participate in one of the three HCBS waivers included under the demonstration (SCDHHS). For

more on use of flexible benefits, please see Section 5, Beneficiary Engagement and Section 7,

Finance and Payment.

New service delivery models. A key feature of the South Carolina demonstration is the

transition of HCBS waiver roles and responsibilities from the State to the MMPs. The SCDHHS

Community Long Term Care (CLTC) division previously had responsibility for these functions

for the three waiver populations included in the demonstration. The phased transition process

was designed to systematically introduce these functions to the MMPs while preserving the

State’s authority until each MMP demonstrated readiness. For more on this activity, please see

Section 2.2.1, Provider Arrangements and Services.

Stakeholder engagement. The Healthy Connections Prime State team has engaged

stakeholders with meetings and presentations throughout the early design and implementation

phases of the demonstration. The Prime team and its contractors have convened work groups to

focus on particular aspects of the demonstration design and made presentations to providers,

provider and beneficiary organizations, and other stakeholders. The State’s contractors engaged

in outreach to stakeholders include SC Thrive, a Medicaid beneficiary outreach organization; the

Office for the Study of Aging at the University of South Carolina, a research and training

organization; and the State’s long-term care ombudsman, who is also the demonstration’s Prime

Advocate or ombudsman.

1.3 Changes in Demonstration Design

The demonstration’s three-way contract called for opt-in enrollment to begin on

January 1, 2015, and for passive enrollment to begin in April 2015. The South Carolina

legislature passed a proviso in spring 2015 to delay passive enrollment until April 2016, thus

requiring the demonstration to have 14 months of opt-in enrollment, resulting in a very limited

enrollment during that period (see Section 3, Eligibility and Enrollment for a discussion on this

topic). This delay also caused a postponement in the transition of the HCBS waiver function to

7

the MMPs from the State. Initially, these functions were to roll out in three phases, from January

2015 through December 2016 (South Carolina three-way contract, pp. 262–73). The delay in the

start of the demonstration and of passive enrollment necessitated a longer transition of the HCBS

waiver functions from the State to the MMPs that began in February 2015 and concluded in

April 2017. One of the HCBS waiver functions did not transfer from the State to the MMPs: by

mutual agreement between the MMPs and the State, oversight of beneficiary self-directed

attendant care workers continued to be delivered by the State. In November 2017, the three-way

contract was re-executed to update the demonstration year dates and to bring the contract into

alignment with certain State and Federal guidelines and program requirements (CMS, 2017a).

In July 2018, CMS and the State announced changes to the South Carolina demonstration

that include: (1) extending the demonstration to December 31, 2020 with all three MMPs,

(2) allowing passive enrollment of eligible beneficiaries who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage

plans, (3) allowing passive enrollment of eligible beneficiaries who reside in counties with only

one MMP, (4) reduction to shared savings effective 2018, and (5) a reduction in some reporting

and other administrative requirements. These changes fall outside the reporting period of this

report and will be discussed in future reports.

1.4 Overview of State Context

This section discusses South Carolina’s experience with managed care, available waiver

services, and effects of changes in State leadership. For a summary of predemonstration and

demonstration design features for Medicare and Medicaid enrollees in South Carolina, see

Appendix E.

State leadership and MLTSS consideration. In fall 2016, the State’s Medicaid Director

announced a suspension of passive enrollment into the demonstration, effective January 1, 2017.

The State engaged external subject matter experts to assess whether an MLTSS program,

including a population not limited to those over age 65, would be more practical for the State.

Subsequently, the Medicaid Director left that position and passive enrollment in the

demonstration was restored in August 2017, but discussions about possibly transitioning the

demonstration to a MLTSS program continued throughout 2017.

A new Medicaid Director was not confirmed until early 2018. During the period from fall

2016 through the informant interviews conducted in fall 2017, MMPs, providers, and

stakeholders were uncertain whether the demonstration would continue beyond December 2018.

It is not clear whether demonstration enrollees were aware of what stakeholders commonly

called “a cloud of uncertainty” over the demonstration. In July 2018, when CMS and the State

announced an extension of the demonstration through 2020, State officials explained that the

State was continuing to study the ramifications of implementing an MLTSS product for all

dually eligible beneficiaries in the State. Any implementation would begin after the close of the

demonstration.

Experience with managed care. From the beginning of the Healthy Connections Prime

demonstration, the RTI evaluation team heard reports that managed care was relatively new in

the State and that providers were generally distrustful of contracting with managed care

organizations, including Healthy Connections Prime plans. Individual providers, such as home

8

health agencies and nursing facility owners, were particularly hesitant to engage with plans and

often opted for single case contracts for an individual enrollee, rather than contracting more

broadly with the MMP. The basis of their concern was fear of not being paid on time or as

agreed. Providers and stakeholders reported that this concern was well founded. For example,

large practices and small individual providers told of not being paid for services rendered despite

prior authorizations or approvals by Medicare Advantage plans operating in the State.

Healthy Connections Prime plans reported that Medicare Advantage plans and their

brokers provided negative or misleading information to beneficiaries about the viability of the

demonstration. This activity increased during the period of uncertainty beginning in fall 2016,

when the State paused the passive enrollment process to consider a possible change to MLTSS.

The State advised MMPs to collect details about such incidents and inform CMS and the State.

CMS researched these incidents using a “secret shopper” contractor to pose as beneficiaries. The

Center for Medicare issued a technical assistance letter to one managed care plan and contacted

another plan’s account manager to clarify instructions and guidance regarding appropriate

marketing. Similar activity from other managed care plans, agents, and brokers continued and

CMS pursued all complaints; however, obtaining first-hand evidence for these types of activities

is extremely difficult.

The State had originally introduced managed care in 1996 through risk-based managed

care organizations (MCO) serving children, pregnant women, and adults with disabilities who

were not dually eligible. Services included primary, acute, some specialty care, and outpatient

behavioral health services. Enrollment was limited until 2006, when Healthy Connections

Choices, an enrollee support program, was introduced. Operated by the State’s enrollment

vendor, Maximus, Healthy Connections Choices advised Medicaid beneficiaries that they could

choose from three Medicaid delivery models: an MCO, a primary care case management

program, or the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) option. In 2011, South Carolina required

Medicaid beneficiaries to enroll in either an MCO or a Medical Home Network (MHN) and in

January 2014, the MHNs were transitioned to MCOs. Exempted from mandatory Medicaid

managed care are children in foster care, children with disabilities, Medicaid waiver enrollees,

beneficiaries receiving institutional care, and dual eligible beneficiaries.

The State contracts with five plans to provide services to Medicaid managed care

enrollees: Absolute Total Care (Centene), Molina of South Carolina, BlueChoice Health Plan,

WellCare of South Carolina, and First Choice Select Health. These MCOs pay providers

capitated rates for each enrollee assigned to their practices. Three of these MCOs (Absolute

Total Care, Molina of South Carolina, and First Choice Select) are Healthy Connections Prime

demonstration plans. Advicare was initially contracted as an MMP, but when its Medicaid

managed care product was purchased by WellCare in August 2016, it withdrew from the

demonstration. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) do not have a significant presence in

South Carolina, according to State officials.

In 2017, approximately 243,030 beneficiaries, about one-quarter of South Carolina’s

Medicare beneficiaries, received care through Medicare Advantage plans. UnitedHealth group,

Humana, and Aetna accounted for 92 percent of the coverage. Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries

participating in Medicare Advantage may receive care through four special needs plans for

dually eligible beneficiaries (D-SNP) operating in South Carolina. In 2017, approximately

9

24,364 individuals received care through D-SNPs (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017). Three

PACE plans are available in the State; enrollment in those plans was 439 as of December 2017

(CMS, 2018b).

HCBS waivers. For individuals with disabilities or complex care needs, South Carolina

operates nine HCBS waivers. Each waiver targets individuals with a unique set of disabilities

and provides appropriate services to them. Beneficiaries participating in three of the nine

waivers, the HIV/AIDS, Mechanical Ventilation Dependent, and Community Choices HCBS

waivers, are eligible to participate in the South Carolina demonstration. The Community Choices

waiver is designed for individuals who require a nursing home level of care and assistance with

their activities of daily living. These waiver enrollees may direct services including hiring their

own personal assistance, respite and companion service providers. Beneficiaries from the

remaining six HCBS waivers (Intellectual Disabilities and Related Disabilities, Head and Spinal

Cord Injury, Community Supports, Medically Complex Children’s, Pervasive Developmental

Disorder, and Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility Alternative Chance) are not eligible to

participate (MOU, 2013).

Federal funding. South Carolina received $4.5 million in Federal funds in September

2014 to support Healthy Connections Prime planning and implementation. The State used these

funds to contract vendors to assist with developing the demonstration. Vendors include

Maximus, the State’s enrollment broker; Ikaso Consulting for marketing support; SC Thrive for

beneficiary education and outreach; and the University of South Carolina to develop and provide

courses for the MMPs, providers, and stakeholders. Federal funding for planning and

implementation continued in the second demonstration year ($2.8 million) and the State

contributed $0.9 million.

The State Long Term Care Ombudsman office, which functions as the demonstration’s

ombudsman or Prime Advocate, was awarded $246,493 in 2015 by CMS in collaboration with

the Federal Administration for Community Living (ACL). This office received $297,254 in 2016

and the same amount in 2017 to support these services.

10

[This page intentionally left blank.]

11

2. Integration of Medicare and Medicaid

This section provides an overview of the management structure that was created to

oversee the implementation of the demonstration and discusses in greater detail the organization,

geographic coverage areas, and the four initial Healthy Connections Prime plans that were

selected to integrate and deliver the Healthy Connections Prime. It also provides a general

description of the other functions (e.g., care coordination, eligibility, enrollment, quality

management, and financing) that SCDHHS, CMS, and the plans had to coordinate or integrate as

part of the implementation of the demonstration. Later sections provide more in-depth discussion

of the implementation successes and challenges associated with the integration of these

functions.

2.1 Joint Management of Demonstration

The CMS-State contract management team (CMT) monitors the MMPs and oversees

nearly every aspect of the demonstration including marketing, enrollment, grievances and

appeals, and the MMPs’ compliance with providing certain services within required timeframes.

The CMT is responsible for monitoring to ensure that State and CMS policies are integrated, to

respond to MMPs’ questions and concerns, and to identify areas for technical assistance.

The CMS team members initially included two representatives from the MMCO, one

Consortium for Medicare Health Plans Operations (CMHPO) staff, and one Consortium for

Medicaid and Children’s Health Operations (CMCHO) staff. By 2017, the MMCO and CMCPO

staff members participated. State members of the CMT include several core Healthy Connections

Prime team members, and, depending upon the discussion topic for the meeting, other key State

Highlights

• Medicare-Medicaid Plans (MMPs) provide the administrative structure to integrate the

financing and delivery of primary and acute care, behavioral health, and long-term

supports and services (LTSS).

• The slow rollout of the demonstration, due to the passive enrollment delay, provided

time for the MMPs to receive training and hone their skills in LTSS and HCBS waiver

services.

• Advicare, one of the four original MMPs, left the demonstration effective August 31,

2016. Most enrollees who had been covered by Advicare were transferred to other

MMPs. As of December 2017, 39 of the 46 counties were covered by the

demonstration.

• MMPs satisfied their provider network requirements despite hesitant participation by

some providers—including hospitals, nursing facilities, and personal care providers—

due to their fear of managed care. MMPs have used single-case contracting to provide

continuity of care of enrollees and to build relationships with providers.

12

staff. The State’s Prime Advocate or ombudsman for Healthy Connections Prime, who is in the

Long Term Care Ombudsman office in the State’s Office on Aging, joined the CMT in March

2015.

Noting their limited Medicare expertise, State staff reported they relied on the knowledge

of the CMS CMT members to provide details and context of various Medicare regulations and

requirements. MMP interviewees reported that they appreciated the CMT’s quick responses to

policy and procedural issues as a result of having Medicare, Medicaid, and State staff available

in the same meeting. All parties remarked on the effectiveness of this “team approach.” The team

initially met bi-weekly with each MMP to review activities, to provide them with feedback

reports to help them benchmark their performance, and to respond to questions.

As the demonstration has evolved, so have the activities of the CMT. By 2017, the CMT

was meeting monthly with each plan. The monthly, State-led operational meeting with all plans

discusses the MMPs’ operations reports that show monthly trends of (1) the ratio of care

coordinators to active enrollees; (2) enrollee counts of those receiving flexible or waiver-like

services; (3) open and closed grievances and appeals; (4) issues tracking by low, medium, and

high priority areas, and other relevant topics. This report also includes the results of MMPs’ exit

interviews with enrollees who have disenrolled from each plan.

2.2 Overview of Integrated Delivery System

2.2.1

Healthy Connections Prime Plans

After a competitive bidding process and extensive readiness reviews, South Carolina and

CMS contracted with four Medicare-Medicaid Plans (MMPs), (originally known as Coordinated

and Integrated Care Organizations or CICOs) to authorize, integrate, and coordinate the full

range of Medicare and Medicaid services including primary, acute, and behavioral health care,

and institutional and community-based LTSS, and a new palliative care benefit. The four MMPs

had extremely varied backgrounds; two had extensive experience with Medicaid managed care in

the State. Three did not have State experience integrating Medicare and Medicaid services in a

product such as a D-SNP; one had minimal experience (see Table 1). At the start, the

demonstration covered 41 of the 46 counties; after the Advicare departure 39 counties were

covered. For further discussion of the Advicare departure and the effect on enrollment, see

Section 3, Eligibility and Enrollment.

2.2.2

Provider Arrangements and Services

Plans noted that outside of the three main metropolitan areas (Charleston, Columbia, and

Greenville), most of the counties are rural and have a limited range of specialists, yet MMPs are

required to contract with a full complement of providers in most specialties in each county. Plans

pointed out that some counties do not have cardiologists or oncologists, which precluded the

MMP from operating in particular counties. MMPs believed that these requirements were too

stringent given the number of small counties in the State, and noted that providers located in a

neighboring county might be closer to a beneficiary than providers located in the beneficiary’s

home county. Nevertheless, MMPs contracted with a sufficient number of primary and specialty

13

providers to fulfill the CMS minimum network adequacy requirements prior to the start of the

demonstration.

Table 1

Healthy Connections Prime MMP profiles

Parent

company

Healthy

Connections

Prime MMP

No. of

counties

served as

of January

2016*

No. of counties

served as of

December 2017

Previous

experience with

Medicare

Advantage or

D-SNP

Previous

experience with

Medicaid

managed care

National

chain

Centene

Corporation

Absolute Total

Care (ATC)

32 35 No Yes Yes

Spartanburg

Regional

Healthcare

Advicare

Advocate**

39 0 No Yes No

Molina

Healthcare

Molina

Healthcare of

South Carolina

22 29 No Yes Yes

AmeriHealth

Caritas

Select Health of

South Carolina

38 39 Yes Yes Yes

* Total of 46 counties

** Advicare left the demonstration after its purchase by WellCare Health Plans, Inc., in August 31, 2016.

SOURCE: SCDHHS monthly enrollment dashboards (South Carolina 2018).

Provider reluctance. As discussed in Section 1.4, Overview of State Context, some

providers were reluctant to contract with MMPs, explaining that this was due to the poor

reputation of Medicare Advantage plans operating in the State. Other providers noted their lack

of experience with, and a general fear of, managed care plans. These factors contributed to

MMPs’ difficulty in developing robust provider networks with which they could develop value-

based purchasing agreements. See Section 7, Financing and Payment for more on this topic.

Con

tin

uity of care. Although skilled nursing facilities, individual providers, and some

large healthcare networks declined to enter into contractual arrangements with MMPs, they

chose to enter into single case contracting with MMPs as needed. The demonstration’s continuity

of care provision allows for enrollees to continue seeing their previous provider up to six months

prior to transitioning to a Healthy Connections Prime provider (SCDHHS, 2017). In RTI’s

annual site visit interviews, the team consistently heard from MMPs that most providers readily

engaged in single case agreements for enrollees as needed. The MMPs used these agreements to

build relationships with providers that often led to full contracts.

Behavioral health providers. Plans contracted with the State Department of Mental

Health (DMH) for the provision of behavioral health services in their community health centers

located in each county. Because of limited capacity of these providers and low utilization by

aging beneficiaries, the State encouraged MMPs to also contract with private behavioral health

providers. MMPs may, but are not required to, contract with the Department of Alcohol and

14

other Drug Abuse Services, which provides treatment for substance use; they also contract with

private providers for these services.

By summer of 2016, of the more than 9,000 enrollees, only 149 (1.7%) were receiving

services from DMH providers. By 2017, the State and the plans reported low overall utilization

of mental health and behavioral health services. Challenges included the State’s lack of capacity

to serve the aging population; the DMH’s reported reluctance to treat beneficiaries who have a

primary diagnosis of dementia; and providers’ focus on disruptive behavior, while conditions

such as depression were under-treated (please see Section 5, Beneficiary Experience for more

on this topic).

Transition of HCBS waiver services. A key feature of the South Carolina

demonstration is the transition of HCBS waiver roles and responsibilities from the State to the

MMPs. The SCDHHS Community Long Term Care (CLTC) division has had responsibility for

these functions for the three waiver populations included in the demonstration. The phased

transition process, developed with significant stakeholder input, was designed to systematically

introduce these functions to the MMPs while preserving the State’s authority until each MMP

demonstrated readiness. Table 2 shows the transition schedule for HCBS waiver functions.

Table 2

Transition of HCBS waiver functions from State to MMP

HCBS waiver functions

Phase I

February 2015

Phase II

September 2016

Phase III

April 2017

HCBS provider credentialing/monitoring State State

State; MMP may

choose responsibility

HCBS provider contracts State MMP MMP

HCBS care plan development & authorization

State with MMP

formal input

MMP with State

approval

MMP with State

approval

Oversight of State waiver case manager’s

participation in multidisciplinary team

MMP MMP MMP

HCBS provider rate setting State

MMP within State

guidelines

MMP within State

guidelines

HCBS claims processing via Care Call and

provider payments

1

State MMP MMP

1

LTC level of care assessments State State State

LTC level of care reassessments State MMP MMP

2

Self-directed attendant care and related

functions

State State State

3

HCBS = home and community-based services; LTC = Long term care; MMP = Medicare-Medicaid Plan.

1

Per mutual agreement, the State has retained responsibility for processing HCBS provider payments; MMPs’

Medicaid capitation includes HCBS; therefore, these payments are subsequently reconciled

2

Effective July 1, 2018, MMPs are responsible for approving the LTC reassessments.

3

The July 1, 2018 contract amendment lists the MMP as having this responsibility for Phase III although the State

will continue to have responsibility.

SOURCES: CMS amendment to South Carolina three-way contract (July 1, 2018) and South Carolina Healthy

Connections Prime Demonstration contract re-execution (November 1, 2017).

15

Phases 1, 2, and 3 were originally scheduled to be completed by December 2015, June

2016, and December 2016, respectively, but were adjusted due to the delay in passive

enrollment. Approximately 200 of the 1,800 beneficiaries (11.1%) who opted into the

demonstration during the first year were HCBS waiver participants. After the April and July

2016 passive enrollment waves, approximately 1,500 waiver participants joined the

demonstration. By December 2017, 1,738 waiver participants were enrolled. Section 4, Care