BIRD

SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

2 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

Thank you to New York City Audubon and their original working group

for permission to revise their Bird-Safe Building Guidelines (May 2007).

NYC Project Director: Kate Orff, RLA, Columbia University GSAPP

NYC Authors: Hillary Brown, AIA, Steven Caputo, New Civic Works

NYC Audubon Project Staff: E.J. McAdams, Marcia Fowle, Glenn Phillips,

Chelsea Dewitt, Yigal Gelb Graphics.

NYC Reviewers: Karen Cotton, Bird-Safe Working Group; Randi

Doeker, Birds & Buildings Forum; Bruce Fowle, FAIA, Daniel Piselli,

FXFOWLE; Marcia Fowle; Yigal Gelb, Program Director, NYC Audubon;

Mary Jane Kaplan; Daniel Klem, Jr., PhD., Muhlenberg College; Albert M.

Manville, PhD., US Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service;

E. J. McAdams, Former Executive Director NYC, Audubon; Glenn

Phillips, Executive Director, NYC Audubon.

Original publication of these guidelines was made possible with the

support of US Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service

through the Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act, Joseph &

Mary Fiore and the support of NYC Audubon members and patrons.

Bird-Safe Building Guidelines

Over 100 bird species have been recovered from building collisions in Minnesota including Lincoln’s Sparrow, Black-capped Chickadee, Indigo Bunting, Common Yellowthroat, and Nashville Warbler

The mission of Audubon Minnesota is to conserve and restore natural

ecosystems, focusing on birds and their habitats, for the benefit of

humanity and the earth’s biological diversity.

AUDUBON MINNESOTA

2357 Ventura Drive, Suite 106

• Saint Paul MN 55125

mn.audubon.org

Published by Audubon Minnesota, May 2010

Project Director: Joanna Eckles (Audubon Minnesota)

Contributor: Edward Heinen (Perkins + Will)

Reviewers: Mark Martell, Mark Peterson (Audubon Minnesota); Lori

Naumann (Minnesota Department of Natural Resources); Chris

Sheppard (American Bird Conservancy); Susan Elbin (NYC Audubon);

Jonee Kulman Brigham (Center for Sustainable Building Research,

UMN), Benjamin Sporer, Paul Neuhaus (Perkins + Will)

Design Manager: Bonita Jenné (Audubon Minnesota)

Cover Cityscape Artwork: Edward Heinen

Printing made possible by TogetherGreen

Citation: Audubon Minnesota. (2010). Bird-Safe Building Guidelines

Photographs in this publication are copyrighted by the individual

photographers and have been used with permission. Site and lighting

diagrams courtesy of the City of Toronto from their Bird-Friendly

Development Guidelines.

JIM WILLIAMS

JIM WILLIAMS

MIKE LENTZ

MIKE LENTZ

MIKE LENTZ

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 3

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

BIRDS AND BUILDINGS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Birds and the Built Environment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Birds and Building Green. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Causes of Collisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Factors Affecting Bird Collisions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Project BirdSafe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Comprehensive Planning for Bird Conservation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Site and Landscape Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Building Layout and Massing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Exterior Glass . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Emerging Technologies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Lighting Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Building Operations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Comprehensive Site Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Modifications to Existing Buildings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

CASE STUDIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

RESOURCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Products and Innovations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Local Resources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

MIKE LENTZ

Dark-eyed Junco

4 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

Bird-building collisions

are an unfortunate side

effect of our expanding

built environment and

a proven problem

in Minnesota and

throughout the world.

These are just a portion

of the birds collected

from Toronto window

collisions in 2009.

KENNETH HERDY

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 5

INTRODUCTION

G

LAZED BUILDINGS THAT MAKE UP MODERN CITY

skylines and suburban settings along with countless windows

in our homes present serious hazards for birds. In the United States,

hundreds of millions of birds perish each year from collisions with

buildings.

1

In Minnesota, bird-window collisions are a proven problem. Over

100 species of birds have been documented at just a small number of

buildings being monitored throughout the state. Birds are killed or

injured as a result of clear and reflective glass. Artificial lighting also

confounds night-migrating species.

In addition, increased interest in “building green” often results

in both desirable habitat for birds and large expanses of glass – a

deadly combination.

Fortunately, awareness and preventative actions are emerging.

Internationally, Lights Out programs are aiding night migrants in a

growing number of cities. And by incorporating bird-safe building

design strategies as part of an integrated sustainable design program,

we can help save countless resident and migratory birds.

These Bird-Safe Building Guidelines expand upon ongoing Project

BirdSafe initiatives in Minnesota to address bird-building collision

issues at the building design level. Utilizing New York City

Audubon’s 2007 Bird-Safe Building Guidelines and other resources,

established standards for bird-safe building enhancements have

been updated and adapted to provide local examples and references.

These guidelines are intended for use by those involved in building

design and operations. They promote measures to protect birds in

the planning, design, and operation stages of all types of buildings,

in all settings and have been updated to reflect implementation

criteria in LEED® v3 (2009).

Bird-safe building criteria are scheduled to be incorporated into B3

State of Minnesota Sustainable Building Guidelines (B3-MSBG)

in 2010. B3-MSBG is required for all new construction and major

renovations that receive state bond money. B3-MSBG covers the

planning, design, construction, and operation of buildings.

2

DID YOU KNOW?

Birds are an important asset to the travel and recreational sectors of the economy. According to the

United States Fish and Wildlife Service, bird-watching is the second fastest growing leisure activity in

North America. An estimated 63 million Americans participate in wildlife watching and eco-tourism

each year. In the process, they spend close to $30 billion annually, with a major portion related to

birds.

3

With fully one-third of Minnesotans self-identifying as bird-watchers,

4

the health of our birds and

their habitats is economically as well as ecologically imperative.

“Architects And

their clients cAn

use All the recycled

mAteriAl they wAnt.

they cAn sAve All the

energy they wAnt,

but if their building

is still killing birds,

it’s not green to me.”

Dr. Daniel Klem,

Muhlenberg College,

Audubon, Nov-Dec 2008

Injured Golden Crowned Kinglet

NYC AUDUBON

6 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BIRDS AND BUILDINGS

Birds and the Built Environment

DID YOU KNOW?

Buildings contribute substantially to greenhouse gas emissions, which in turn adversely impact native and migratory birds. Building

operations consume over 75% of the electricity in the U.S. In 2007, the commercial building sector alone produced more than 1 billion

metric tons of carbon dioxide, an increase of 4.4% from 2006 levels, and an increase of over 38% from 1990 levels.

6

Research provides clear

evidence of the negative effects of climate change on the migration, breeding, numbers, and behavior of many North American bird species.

7

IN RECENT DECADES, sprawling land-use patterns and

intensified urbanization have degraded the quantity and quality

of bird habitat throughout the globe. Cities and towns cling to

waterfronts and shorelines, and increasingly infringe upon the

wetlands and woodlands that birds depend upon for food and

shelter. Loss of habitat makes city parks, streetscape vegetation,

waterfront business districts, and other urban green patches

important resources for resident and migratory birds. There birds

encounter the nighttime dangers of illuminated structures and the

daytime hazards of dense and highly glazed buildings.

The increased use of glass poses a distinct threat to birdlife. From

urban high-rises to suburban office parks to single-story structures,

large expanses of glass are now routinely used as building enclosure.

Energy performance improvements in transparent exterior wall

systems have enabled deep daylighting of building interiors, often

by means of floor-to-ceiling glass expanses. The aesthetic and

functional pursuit of still greater visual transparency has spurred the

production of ultra-clear glass.

The combined effects of these factors have led scientists to

determine that bird mortality caused by building collisions is

a biologically significant

5

issue. In other words, it is a threat of

sufficient magnitude to affect the viability of bird populations,

leading to local, regional, and national declines.

Songbirds – already imperiled by habitat loss and other

environmental stressors – are especially vulnerable during migration

to daytime and nighttime collisions as they seek food and shelter

among urban buildings. Researchers have documented hundreds of

thousands of building collision-related bird deaths nationally during

migration seasons. Included in this toll are specimens representing

over 225 species, a quarter of the species found in the United States.

Stunned Brown CreeperLow-density development generally results in habitat loss Architectural trends favor use of glass

Bird populations,

already in decline from

loss of habitat, are

further threatened by

the incursion of man-

made structures into

avian air space.

JOEL DUNNETTE

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 7

A green roof is one way we “build green” American Redstarts weigh less than 1/2 ounce but their migration route may cover more than 2500 miles

Birds and Building Green

SUSTAINABLE, HIGH-PERFORMANCE BUILDINGS are

designed to conserve energy and reduce carbon emissions, conserve

water resources, harvest daylight and provide healthy indoor

environments. These buildings conserve and recycle materials and

display unprecedented levels of environmental responsibility and

functionality. They are integrated with their natural surroundings

and often enhanced with native landscaping.

The green building movement is an exciting advancement for

architects, designers, building users and conservationists alike.

But it is not without pitfalls. Unless carefully considered, greening

efforts may actually contribute to the loss of the very creatures we

seek to protect. Ironically, in our desire to bring the outside in,

we may increase risks to birds. By attracting birds in and around

glazed buildings we inadvertently increase the risk of bird-window

collisions. Better sustainable design practices therefore demand that

buildings also be designed to integrate specific bird-safe strategies.

“there is nothing

in which the birds

differ more from

mAn thAn the wAy

in which they cAn

build And yet leAve A

lAndscApe As it wAs

before.”

Robert Lynd, The Blue Lion

and other essays

Advocating bird-safety in buildings should be integral to the green

building movement. Many of the strategies for reducing bird

collisions complement other sustainable site and building objectives.

In concert, efforts to reduce collision hazards, enhance and restore

habitat and conserve energy help native and migratory birds.

While development poses a myriad of risks to birds, the movement

towards sustainability and collaboration offers hope. Those

leading the shift to building green are well suited to stimulate the

development of new glazing technologies and to create a market for

all bird-safe building products. If builders and developers demand

it, much-needed advancements will follow.

Bird populations are remarkably resilient and can respond well to

conservation efforts. By incorporating bird-safe building design

strategies as part of an integrated sustainable design program, we

can help birds thrive in our built environment.

MIKE LENTZ

8 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BIRDS AND BUILDINGS

Causes of Collisions

DAYTIME COLLISIONS occur because most birds do not perceive glass as an obstacle. Migratory birds in particular have not evolved

to live in built environments and don’t see the context cues that indicate that glass is solid.

8

Instead they see the things they know and need,

such as habitat and open sky, reflected in the glazed surface or on the other side of one or more panes of glass.

Collisions occur at glass facades of all sizes, in all seasons and weather conditions, and in every type of environment from residential and

rural settings to dense urban cores. Collisions and mortality occur at any place where birds and glass coexist.

1

As a result, daytime collisions

are likely the most prevalent of all building collision hazards.

Birds have two key

issues with buildings –

one relates to glass, the

other to lighting.

From outside most buildings, glass often appears highly

reflective. Under the right conditions almost every type

of architectural glass reflects the sky, clouds, or nearby

trees and vegetation, reproducing a perceived habitat

familiar and attractive to birds. Birds fly from the real

habitat to the reflected habitat or sky and hit the glass

in between.

PROBLEM GLASS REFLECTIVITY: MIRROR EFFECT

The trick of transparency is exacerbated when windows

are installed directly across from one another or at

a corner because birds perceive an unobstructed

passageway and attempt to fly through the glass. In

Minnesota, glass linkways and skyways are commonly

used to protect people from the elements and often

cause bird collisions.

PROBLEM GLASS TRANSPARENCY: FLY THROUGH

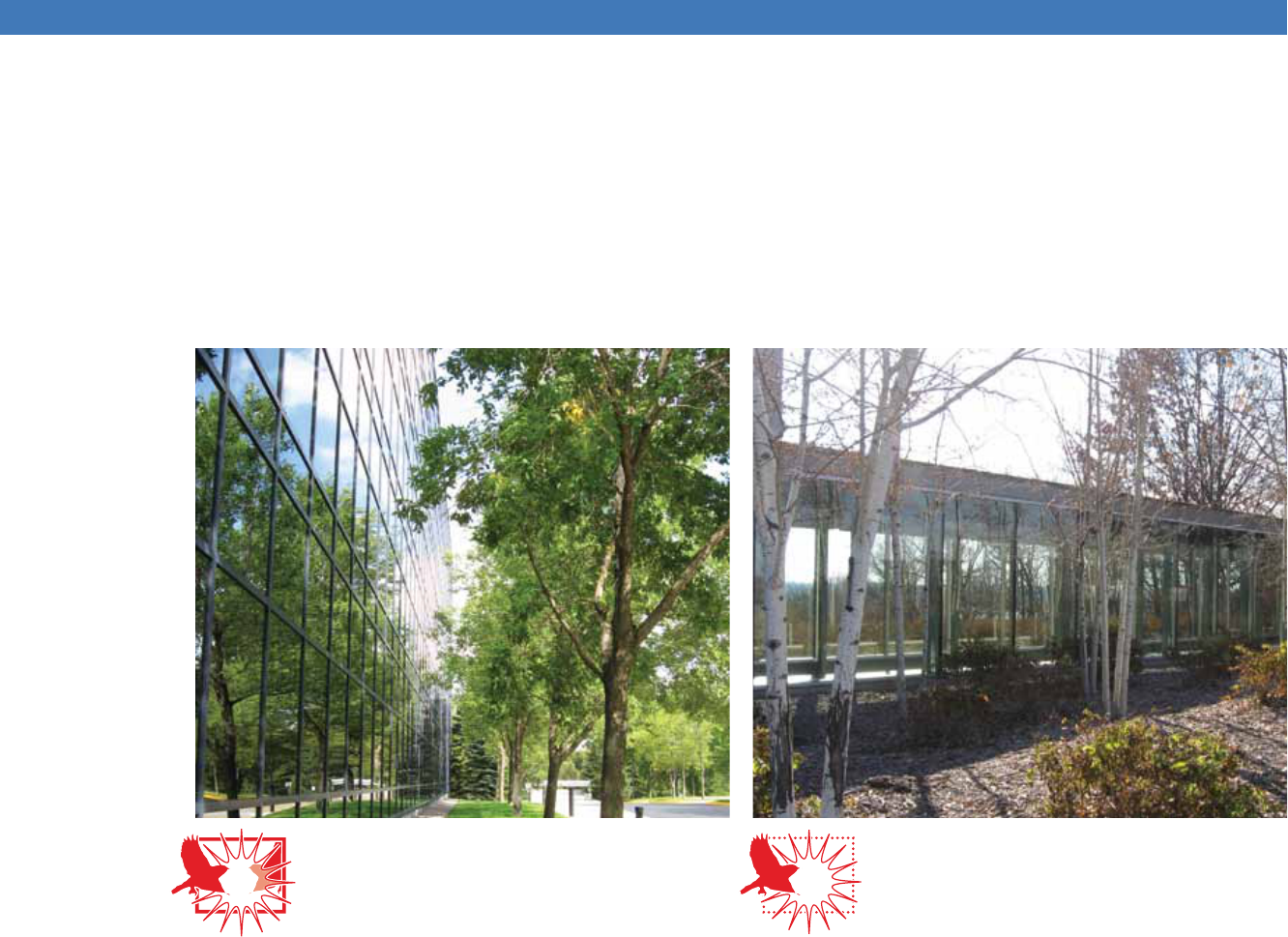

Problem: Reflection Problem: Transparency

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 9

NIGHTTIME COLLISIONS occur because the illumination of buildings creates a beacon effect for night-migrating birds. When

weather conditions are favorable, these birds tend to fly high (over 500 feet) and depend heavily on visual references to maintain their

orientation. However, during inclement weather, they often descend to lower altitudes, possibly in search of clear sky celestial clues or

magnetic references and are liable to be attracted to illuminated buildings or other tall lighted structures.

Night lighting also affects daytime collisions by temporarily increasing the number of migratory birds in urban areas. When the sun rises and

those “trapped” birds begin to move about, forage or seek an escape, they often encounter the deadly effects of reflective and transparent glass.

Heavy moisture (humidity, fog or mist) in the air greatly

increases the illuminated space or “skyglow” around buildings,

regardless of whether the light is generated by an interior or

exterior source. Birds become disoriented and entrapped

while circling in the illuminated zone and are likely to succumb

to exhaustion, predation, or lethal collision.

When night-migrating birds become trapped in a dense urban

area they often fly towards illuminated lobbies and atria on

lower levels. Potted plants inside the glass can be a deadly lure

as birds seek safety and do not perceive the glass in their way.

DID YOU KNOW?

In addition to the adverse impacts on migrating birds, significant economic and health incentives exist for curbing light pollution. Overly lit

buildings waste tremendous amounts of electrical energy, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution levels, and of course, wasting

money. Researchers estimate that the United States alone wastes over one billion dollars on electricity annually because poorly designed or

improperly installed outdoor fixtures allow much of the lighting to go up to the sky.

9

In addition to the threat this poses to birds and other

animals, “light pollution” has significant aesthetic and cultural impact as well. Studies estimate that over two thirds of the world’s population

can no longer see the Milky Way, which humans have gazed at with a sense of mystery and imagination for millennia. Together the ecological,

financial and aesthetic/cultural impacts of excessive lighting serve as compelling motivation to reduce and refine light usage.

“even the dArkness

moves with the

pAssAge of birds.

on soft spring

midnights, the Air is

Alive with the flight

notes of unseen

birds filtering

down through the

moonlight like the

voices of stArs.”

Scott Weidensaul,

Living on the Wind

PROBLEM ILLUMINATED ATRIA

PROBLEM BEACON EFFECT

Problem: Beacon

effect, illumination

NYC AUDUBON

10 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

Factors Affecting Bird Collisions

PROXIMITY TO STOPOVER LOCATIONS. Birds make stopovers in

waterfront, wetland, grassland, and wooded environments that are now

America’s most densely populated urban areas. Migrating birds have a

significant chance of encountering at least one major metropolitan area

during migration between breeding and wintering grounds. Birds need

stopover sites to refuel. Building sites located near bird feeding areas,

waterfront habitat, or patches of urban vegetation experience increased

risk of bird collisions.

MIGRATION. Collisions tend to increase each spring and fall when

local bird populations are boosted by a huge influx of migrants traveling

between breeding and wintering grounds. Songbirds travel primarily at

night in a “broad-front” migration following several major flyways. These

historic routes follow major rivers, coastlines, mountain ranges, and

lakes. Along the way densely built urban areas have become migration

danger zones.

PLANNING BIRD-SAFE ENVIRONMENTS for both new and existing buildings requires an assessment of existing conditions.

Conditions affecting bird collisions include migration, proximity to stopover locations, proximity to feeding grounds, glass coverage and

glazing characteristics, building orientation and massing features, lighting, weather conditions, and building height.

MIGRATION

IN MINNESOTA

Minnesota is on the

Mississippi Flyway.

About 40% of all

North American

waterfowl and 326

species of birds (1/3

of all species in North

America) use the

Mississippi Flyway on

their spring and fall

migrations. Our peak

migration months are

May, September and

October.

BIRDS AND BUILDINGS

Radar captures masses of migrating birds as seen from each station Glass hi-rise near key habitat

S.A. GAUTHREAUX, JR.

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 11

PROXIMITY TO FEEDING AND HABITAT AREAS. Sites bordering

parkland, pocket parks, habitat patches, green roofs, and street-tree

corridors threaten birds since they forage in these areas for food.

Building sites near water bodies and wetlands – no matter how small

– put both resident and migrant species at risk. Suburban building sites

with proximity to natural landscapes also present a range of hazards and

can be even more dangerous to birds than urban settings.

GLASS COVERAGE AND GLAZING CHARACTERISTICS. A major

determinant of potential strikes is the sheer percentage of glass used on

the building facade. In general, collisions will occur wherever glass and

birds coexist. Ground level and low stories are the major collision zones.

At these levels large expanses of monolithic glazing should be minimized,

glazing reflectivity (especially when adjacent to landscapes) reduced, and

“fly-through” situations eliminated.

BUILDING ORIENTATION AND MASSING FEATURES. Since

migratory routes are broad and flight patterns vary, one cannot simply

address building facades that face an assumed direction of migration.

The impacts of all facades, with special emphasis on those adjacent to

landscapes or other features attractive to birds, must be considered.

For example, landscaped courtyards and glass vestibules can be very

confusing and difficult for birds to negotiate.

LIGHTING AND WEATHER. Regions that are prone to haze, fog, mist,

and/or low-lying clouds may see more frequent bird-kills, especially if the

area contains tall buildings that are highly illuminated. Generally, there are

fewer birds aloft during precipitation; however, inclement weather can

develop, reducing their navigational awareness and forcing them to fly at

lower altitudes in search of visual clues. Heavily illuminated buildings in

their path can serve as deadly lures.

Birds use urban green spaces

How a building is situated on a property affects collision rates Bright lighting oriented skyward draws birds in

Glass confuses birds by reflecting sky or habitat

NYC AUDUBON

NYC AUDUBON

12 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BUILDING HEIGHT

TALLEST:

While birds’ migratory paths vary, radar tracking has determined that

approximately 98% of flying vertebrates (birds and bats) migrate at

heights below 1640 feet during the spring, with 75% flying below that

level in the fall.

10

Today, many of the tallest buildings in the world reach

or come close to the upper limits of bird migration.

11

Storms or fog,

which cause migrants to fly lower and can cause disorientation, can put

countless birds at risk during a single evening. Any building over 500 feet

tall is an obstacle in the path of avian nighttime migration and must be

thoughtfully designed and operated to minimize its impact.

MODERATE HEIGHT:

Buildings between 50 and 500 feet tall pose hazards since migrating

birds descend from migration heights in the early morning to rest and

forage for food. Migrants also frequently fly short distances at lower

elevations in the early morning to correct the path of their migration,

making moderate-height buildings, especially if reflective or transparent,

a serious hazard.

LOWER LEVELS:

The most hazardous areas of all buildings, especially during the day

and regardless of overall height, are the ground level and bottom few

stories. Here, birds are most likely to fly into glazed facades that reflect

surrounding vegetation, sky and other attractive features.

BIRDS AND BUILDINGS

Many urban areas, like Saint Paul (above) have developed along key migration corridors like the Mississippi River

SONGBIRDS & RAPTORS

2,000’

WATERFOWL

SHORE BIRDS

DAYTIME COLLISION ZONE

1,500’

500’

1,000’

250’

Info Credit: Fox & Fowle Architects

Bruce Fowle, E.J. McAdams - 3/11/05

50’

Fox & Fowle Architects - Bruce Fowle, E.J. McAdams, March 11, 2005

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 13

Project BirdSafe

LIGHTS OUT. Bright lights make beautiful skylines but they can also

disorient migrating birds and lead to deadly collisions with buildings.

In 2007 an ongoing Lights Out program was established as a core

Project BirdSafe program. Lights Out was embraced early by both the

Minneapolis and St. Paul Building Owner’s and Manager’s Associations

(BOMA) and had an immediate effect on the Twin Cities skylines.

Lights Out buildings extinguish all possible interior and exterior lighting

after midnight during both spring and fall migration. See page 26.

In 2009 the State of Minnesota passed a “Lights Out” law requiring all of

the over 5,000 state owned and leased buildings to adhere to our Lights

Out criterion in order to save birds and energy.

PARTNERS

Audubon Minnesota

Audubon Chapter of

Minneapolis

Bell Museum of

Natural History

BOMA Greater

Minneapolis

BOMA Saint Paul

DNR Non-game

Wildlife Program

National Parks Service

Perkins + Will

Minneapolis

St. Paul Audubon

Society

Wildlife Rehabilitation

Center

Zumbro Valley

Audubon Society

11:55 pm

12:05 am

PROJECT BIRDSAFE WAS ESTABLISHED IN MINNESOTA in 2007 as a result of growing international concern over the impact

of bird collisions. Minnesota joins a growing network of individuals and organizations working to reduce hazards to birds from building

collisions. Key Project BirdSafe initiatives include Lights Out, research, building monitoring, and bird safe buildings.

RESEARCH AND MONITORING. To answer key questions about the

numbers and types of birds affected by collisions in Minnesota, Project

BirdSafe volunteers monitor specific research routes in downtown

Minneapolis, St. Paul and at Rochester’s Mayo Clinic for dead and injured

birds. These routes, while representing only a tiny subset of Minnesota

structures, are designed to sample a variety of dense urban buildings.

Findings help researchers to better understand some of the local

conditions that contribute to bird collisions.

BIRDSAFE BUILDINGS. Ultimately the work done here and

throughout the world to understand and quantify the problem

of bird-building collisions must lead to action. Those who

design and operate buildings are perfectly positioned to make

design decisions that not only save birds day to day but also

create markets for bird-safe products.

To increase awareness of bird safety in the architecture and

planning community, Audubon Minnesota worked with New York City

Audubon to revise these Bird-Safe Building Guidelines for distribution

in Minnesota. This publication serves as an important first step towards

increasing awareness and adoption of strategies locally to reduce

hazards to native and migratory birds using this key migration corridor.

Minneapolis before and after “Lights Out” on the same April night

Ovenbirds (left) and Nashville Warblers (right) are common Minnesota collision victims

PER BREIEHAGEN

TAMI VOGEL / CLAUDIA EGELHOFF

14 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Comprehensive Planning for Bird Conservation

Objective:

Incorporate bird-

friendly policies and

activities in design

and development of

urban spaces. Raise

awareness of bird

collision issues.

THE INCREASED INTEREST IN BUILDING GREEN creates

genuine opportunities to address broader conservation issues in the

design and planning of our urban and suburban spaces. A building’s

effect on the local, regional, national and international environment

over its lifetime is reflected in energy and resource use, waste

management, daily operations and direct environmental impact.

Bird safety is one clear and direct impact that can be creatively

addressed through collaborative comprehensive planning.

Birds are an ideal focus of community wide conservation efforts

because they are a sentinel of overall environmental health.

Stewardship strategies that benefit birds and their habitats also

benefit a myriad of other plants and animals. These strategies go

beyond those related to buildings and infrastructure just as bird-

friendly design includes more than glass and lighting choices.

These Guidelines encourage participation in natural resource-

based planning to protect and restore native and migratory bird

species of Minnesota. This type of planning benefits communities

by emphasizing vital natural assets, involving citizens in natural

resource monitoring and helping to prevent unwise patterns of

development which lead to disconnected fragments of open space,

poor water quality and diminished community character.

Collaboration among diverse disciplines is a valuable and uniquely

innovative aspect of sustainable design and development. Such an

approach calls upon key participants to work beyond conventional

planning and design that relies on the expertise of specialists

working in isolation. Through collaboration, participants develop

an enhanced understanding of how specialized knowledge can

inform the design process. This new insight creates the potential

for innovative design solutions to protect natural resources while

improving the quality of life for communities.

Key participants in natural resource-based planning include design

and engineering professionals, natural science professionals and

citizen scientists, government agencies, and advocacy organizations.

Prairie planting at Thomson Reuters Native plantings at Aveda headquarters reflect corporate commitment to the environment Renewable energy helps birds

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 15

“by improving our

cities for birds

we enhAnce our

own lives And

the strength of

our community.

protection of birds

in An urbAn AreA

presents pArticulAr

chAllenges thAt

cAn best be met by

developing strong

And creAtive

pArtnerships.”

Kent Warden

Executive Director

BOMA Greater

Minneapolis

BIRDS AND URBAN PLANNING

The Minnesota Land Planning Act, (Minn. Stat. 473.852.869)

requires that communities submit comprehensive plans in

accordance with the Metropolitan Planning Council’s 2030 Regional

Development Framework, which includes protection of natural

resources as a primary goal.

12

Native and migratory birds are a

valuable natural resource.

Several North American cities have made birds a priority. The City

of Chicago has developed a Bird Agenda to showcase, outline and

carry forward city-wide initiatives benefiting birds. They have also

signed an Urban Conservation Treaty for Migratory Birds with the

US Fish & Wildlife Service, an agreement to conserve birds through

education and habitat improvement.

The City of Toronto recently made history by being the first city

to make it mandatory for all new construction to meet specific

standards for bird safety. They have also produced and distributed

a book of Bird-Friendly Development Guidelines

13

and undertaken

a broad Biodiversity Campaign to educate their citizens about the

natural environment in and around Toronto with birds as their

initial focus.

14

There is tremendous potential in our urban centers to make

meaningful behavior adjustments to benefit the natural

environment. Working collaboratively between specialties and

among cities we can create a network of habitat corridors and

safe areas for birds to live and breed or to pass through unharmed

between summer and wintering grounds. In the process we benefit

countless other creatures and ourselves.

Best Practices for Bird Safety

Best Practices included in this section make specific

recommendations toward the planning, design, retrofit, and

operation of buildings to minimize bird collisions. The strategies

included complement the LEED (Leadership in Energy and

Environmental Design) Green Building Rating System™ as well as

the Minnesota Sustainable Building Guidelines (B3-MSBG).

The LEED system is the U.S Green Building Council’s nationally

accepted standard of sustainability for the commercial,

residential, and institutional building industries. Provisions related

to bird safety and landscaping are included in the latest version of

LEED v3 (2009).

LEED challenges practitioners to assess the impact of building and

site development on wildlife, and incorporate measures to reduce

threats that buildings pose to birds. Buildings may be certified

as silver, gold or platinum according to the number of credits

achieved in seven categories:

1. Sustainable Sites (SS)

2. Water Efficiency (WE)

3. Energy and Atmosphere (EA)

4. Materials and Resources (MR)

5. Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ)

6. Innovation and Design Process (ID)

7. Regional Priority (RP)

Additionally, bird-safe building criteria are planned for inclusion

into Minnesota Sustainable Building Guidelines, as part of the

Buildings, Benchmarks, and Beyond Program (B3-MSBG) in 2010.

2

DID YOU KNOW?

If you imagine the most populous North American cities arranged horizontally as a horizon line or “birds-eye view” they cover over 40% of

the width of North America. Many cities are concentrated on key migration routes, making them nearly impossible for birds to avoid.

10

16 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Site and Landscape Design

Objective:

Minimize the potential

for bird collisions when

siting buildings near

existing landscape

features and when

planning new

landscapes in close

proximity to buildings.

A WELL-INTEGRATED SUSTAINABLE DESIGN enhances open space and protects and restores habitat while enhancing the overall

architectural and operational quality of a built facility. Efforts to integrate nature and attract wildlife should be balanced with specific

considerations of a site’s impact on birds. Birds attracted to on-site habitat are vulnerable to collisions with glass. These guidelines encourage

bird-safe design strategies early in the collaborative design process through consideration of site, existing habitat, and bird-safe landscaping.

Analyze the site to determine potential attractions for bird populations.

Consult with an ecologist or bird specialist to inventory the site.

Document the location of nearby vegetated streetscapes and urban

parks.

Identify all sources of food and shelter for migratory and resident bird

populations, including plants, water and other natural features.

Identify human-made features that attract birds, including water

sources, nesting and perching sites, and shelter from adverse weather.

15

CONSIDER SITE ANALYSIS

Site building(s) to reduce conflicts with existing and planned landscape

features that may attract birds.

Where buildings cannot be located away from bird sensitive areas, take

special care in treating windows. See “Exterior Glass” pages 20-21.

Where strategic reductions to building footprint have been made in

order to enhance vegetated open space and habitat, assess site conflicts

and include bird safe treatments.

Use soil berms, furniture, landscaping, or architectural features to

prevent reflection in glazed building facades.

CONSIDER EXISTING HABITAT

LEED

LEED

Coordinate with LEED Credits

SS 5.1 Site Development: Protect or Restore Habitat

Coordinate with LEED Credits

SS 5.2 Site Development: Maximize Open Space

Urban parks attract birds Treat windows near habitat

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 17

WHILE BIRDS COLLIDE WITH BUILDINGS AT ALL LEVELS, ground-level stories are considered the most dangerous because this

is where habitat reflections, glazing and internal planting are often all quite prominent. Analysis of bird collision data over 10 years in New

York City showed that “most collisions were documented to occur during the day at the lower levels of buildings where large glass exteriors

reflected abundant vegetation, or where transparent windows exposed indoor vegetation.”

16

Birds are vulnerable to collisions nearly anywhere glass occurs. Habitat

in proximity to glass exacerbates this threat unless reflections are

avoided or eliminated or visual cues are incorporated in glazing.

When planning new landscapes be aware of reflections and see-through

effects created by habitat in relation to building features. Place plantings

to minimize these effects.

Alternatively, situate trees and shrubs immediately adjacent to the

exterior glass walls, at a distance of less than three feet from the glass.

17

Close proximity will minimize habitat reflections. In addition, if a bird

does try to fly to a reflection at this range, flight momentum will be

minimal, thereby reducing fatal collisions. This planting strategy also

provides beneficial summertime shading and reduces cooling loads.

If any bird-attracting features (food, water, shelter) are in reflective

range of the building(s), use fritting, shading devices or other techniques

to make glass visible. See “Exterior Glass” pages 20-21.

CONSIDER LANDSCAPE PLACEMENT

Birds will mistakenly seek shelter in landscaping located behind glass.

Mask views of interior plantings from outside the building.

Use screening, window films or treatments to make glass visible.

With the increased use of green roof technology, impacts on birds must

be considered.

Treat glass to minimize the reflection of rooftop landscaping in adjacent

building features.

Consider foregoing green roof installation or eliminating access to birds

if reflection in adjacent buildings will occur.

CONSIDER INTERIOR LANDSCAPING

CONSIDER ROOFTOP LANDSCAPING

LEED

Coordinate with LEED Credits

SS 7.1 Heat Island Effect: Non-Roof

SS 7.2 Heat Island Effect: Roof

Dangerous reflections Confusing interior plants

CANOPY HEIGHT

Glass treatments

should be applied to

the height of the top

of the surrounding

tree canopy or the

anticipated height of

surrounding vegetation

at maturity.

13

18 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Building Layout and Massing

Objective:

Include bird-safe

strategies as part of

an integrated design

approach before

construction rather

than retrofitting a

building that proves

problematic.

BIRD-SAFE STRATEGIES do not restrict the ability to design creatively. These guidelines encourage an integrated design approach,

challenging building designers to include bird-safe strategies to enhance aesthetic, functional, and building performance goals. The layout

of individual buildings and their relationship to other structures on the site can affect the number of bird collisions that occur. Building

layout and massing can be planned along with landscaping to minimize the likelihood of bird collisions.

CONSIDER SPECIFIC SITE FEATURES

Ground level stories are the most hazardous areas of all buildings and

should be designed to minimize bird collisions.

Minimize those hazards that bring birds close to buildings such as

vegetation, water and other features.

Provide uniform covering with bird-safe materials, especially adjacent to

landscapes. See “Exterior Glass” pages 20-21.

Use angled glass, between 20 and 40 degrees from vertical, to reflect

the ground instead of adjacent habitat or sky.

18

Clear barriers such as transparent bus-shelters, skyways, linkways,

railings, windscreens and noise barriers create a serious hazard for birds

because they are invisible, causing a deadly fly-through hazard.

Avoid use of transparent materials in these structures in any location

where birds may be present. Use translucent or decorative glazing as

an alternative.

If clear panels of any kind are in use, incorporate surface treatments to

make glass visible. See “Exterior Glass” pages 20-21.

Clear barriers create a deadly hazard for birds

These two birds were fooled by habitat reflections

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 19

“bird sAfety is eAsier

to sell when it

overlAps with other

green strAtegies.

slAnted glAss

reduces solAr heAt

gAin but Also works

to effectively reduce

bird injuries. fritted

glAss reduces heAt

gAin, And if it’s 50%

you cAn still see

through it.”

Jeanne Gang, Studio Gang

Architects, Chicago

Courtyards may contain landscaping and confusing internal corners that

limit bird escape routes. These areas often allow sudden access by people

that flush birds into glass.

Control access to enclosed areas so birds flush away from glass into

open areas.

Treat glass with bird-safe materials so birds see and avoid glass.

Driveways can also cause birds to flush from landscaping into reflective

glazing as vehicles approach.

Ensure routes of escape for birds that are using landscaping along

driveways and access roads.

Take care in routing driveways adjacent to landscaping and reflective

glazing.

Site ventilation grates also present a unexpected danger for birds.

An injured bird that falls onto a ventilation grate with large pores can

become trapped.

Specify ventilation grates with a porosity no larger than 0.8 inches.

13

Cover larger grates with netting.

Never up-light ventilation grates.

Rooftop obstacles such as antennas and media equipment can injure

or kill birds and should be minimized. In poor weather and bright lighting

conditions birds may congregate on and around rooftops.

Co-locate antennas and tall rooftop media equipment to minimize

conflicts with birds.

Utilize self-supporting structures that do not require guy wire supports.

Avoid up-lighting rooftop antennas and tall equipment, as well as

decorative architectural spires. See “Lighting Design” pages 24-25.

Confusing corners with multiple reflections

Birds can fall through grates after hitting windows

20 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

Exterior Glass

MOST BIRD COLLISIONS OCCUR at the glazed surfaces of buildings. While circumstances such as lighting and other obstacles do

contribute, glass areas are the primary focus of bird-safe design and retrofit strategies regardless of the overall site, landscape, layout and

massing features. Bird-friendly glass products can contribute to aesthetics, energy efficiency, and effective daylighting. For bird safety,

efforts focus on creating visual markers to make glass visible to birds and minimize reflection of habitat and sky.

CONSIDER VISUAL MARKERS

Objective:

Prevent bird collisions

with glazed surfaces,

while maintaining

transparency for views,

daylighting and passive

environmental control.

White fritted pattern on glass facade at IAC Offices in New York CityInterior shades and exterior film at the Minneapolis Central Library

“Visual noise” is what allows us to see glass. It is created by varying materials, textures, colors, opacity, or other features and helps to break up glass

reflections and reduce overall transparency.

19

Creating these visual markers can alert birds to the presence of glass as an obstacle. This is the most

effective way to mitigate the danger that glass poses to birds.

Utilize etching, fritting, translucent and opaque patterned glass to

reduce transparency and reflection, while achieving solar shading.

(Note: Although fritting is useful for creating visual noise, it is less

effective at reducing reflectance since it is generally applied on the

interior face of the glass.)

Incorporate windows with real or applied divided lights to break up

large window expanses into smaller subdivisions.

Consider applying acid-etched or sandblasted patterns to glass on the

outside surface to “read” in both transparent and reflective conditions.

Create patterns that follow the “hand-print” rule (below).

Use window films featuring artwork or custom patterns permanently

or on a rotating basis.

Low-reflectivity glass has not been sufficiently tested for bird safety but

may prove beneficial in certain installations.

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

DID YOU KNOW?

Studies show that small birds will attempt to fly through any opening larger than 4 inches wide or 2 inches tall or about the size of a child’s

handprint oriented horizontally. When creating “visual noise” on or around a window, optimal openings are no larger than a small handprint.

19

NYC AUDUBON

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 21

Large expanses of clear exterior glazing do not equate to effective day-

lighting for buildings. In fact, over-glazing can contribute to glare, veiling

reflections, unwanted heat gain, and also bird collisions. Many strategies

used to achieve effective daylighting are compatible with bird safety.

Where appropriate, daylighting strategies such as exterior shading

devices, fritted glass, and diffuse and translucent glass can also help to

prevent bird collisions.

In general, the more untreated glass you have, the greater the risk to

birds, especially on sites that are in predictable migratory and resident

bird areas.

CONSIDER INTEGRATED DAYLIGHTINGCONSIDER INTERIOR AND EXTERIOR TREATMENT

Translucent glass can help balance daylighting and prevent bird collisions

An exterior ceramic framework provides shading and daylighting (New York Times)

Exterior shading or other architectural devices enhance bird safety.

Utilize shading devices, screens, and other physical barriers to reduce

reflectivity and birds’ access to glass.

Incorporate louvers, awnings, sunshades, light shelves or other exterior

shading/shielding devices to reduce reflection and give birds a visual

indication of a barrier.

Consider other highly patterned shading/shielding devices that will

provide visual cues and encourage bird safety.

Interior window treatments can provide visual cues for birds and

reduce both transparency and reflections. They also help reduce light

trespass from buildings. See “Building Operations” page 26.

Design interior window treatments using light-colored solar reflective

blinds or curtains. Partially open blinds during the day.

Close curtains and blinds if evening lighting is utilized.

For best results, consider photo-sensors, timers and other automatic

controls to regulate shading devices, lighting and daylighting.

LEED

Coordinate with LEED Credits

EQ 8.1 and 8.2 Daylight & Views

EA 1 Optimize Energy Performance

WINDOW AREA

Windows constitute

about 25-40 percent

of the wall area of

effectively designed

daylit buildings, an

area very similar to

the windowed area in

non-daylit buildings.

20

22 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

DID YOU KNOW?

Unlike humans, birds perceive UV light as a separate color. In fact,

many birds have feather patterns that are invisible to humans. These

patterns help birds distinguish among species and sexes. UV vision

is also important for feeding and for orientation during migration.

Glass products that either reflect or absorb UV wavelengths are

being tested for bird safety but are not yet readily available.

21

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Objective:

Encourage glass

manufacturers to

advance the search

and development of

innovative technologies

that make glass visible

to birds without visually

impairing glass for

humans.

Emerging Technologies

THE ARCHITECTURE AND BUILDING DESIGN INDUSTRY is perhaps best positioned to press for long-term technological

solutions for bird-safety. Encouraging a technological solution would stimulate research and development in the glass industry, and

encourage wide-ranging innovative product development with beneficial economic consequences.

An innovative technological solution would be widely accepted in the design and construction industry, with beneficial economic

consequences, particularly if it minimized aesthetic impacts and was cost-competitive. Developing effective technologies will require

commitment of time and resources along with the support and leadership of glass and construction industry officials.

CONSIDER INNOVATION

Bird-safe glass may involve novel uses of known manufacturing

processes, new/unexplored technologies or even the use of

polycarbonates. Designers and architects can create demand for bird-

safe technology that has stalled in development due to an uncertain

market for these products.

Encourage manufacturers to offer “bird-safe” patterns as stock

products in a variety of finishes for design flexibility (i.e. ceramic frit,

acid etching, laminated LEDs, electrochromic coatings).

Encourage the development of glass that eliminates reflections. The

exterior surface of glass is of primary concern, however all surfaces of

glass reflect habitat to some extent.

Request plastic films, diachronic coatings, and tints for exterior use.

Utilize existing patterning materials such as ceramic frits and acid

etching for exterior use.

Support research on pattern recognition of both humans and birds

to identify patterns that inhibit the fly-through effect while minimally

obstructing human views.

700 nm

600 nm

500 nm

400 nm

300 nm

WAVELENGTH

UV VISIBLE

Differences in human and avian vision have inspired one type of bird-visible glass –

Ornilux Glass – and much ongoing research

Human-visible Bird-visible

ROBERT BLEIWEISS, PROCEEDINGS OF

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

NYC AUDUBON

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 23

Ornilux Glass was recently installed at the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Center for

Global Conservation in Bronx, New York

CONSIDER NEW TECHNOLOGY

The development of an integral glass technology would greatly reduce

the problem of building-related bird mortality without imposing major

aesthetic modifications to contemporary building designs.

Develop glass with integral patterns in the ultra-violet range that will be

visible to birds and not humans.

21

Experiment with particles that can be cast integrally into glass during

the production process.

Encourage the development of other forms of non-reflective tinted or

spectrally selective glass.

LEED

Coordinate with LEED Credits

EQ 8.1 and 8.2 Daylight & Views

ID 1 to 1.4 Innovation in Design

Research and New Product Development

The need for readily-available, cost-effective and aesthetically

acceptable products that effectively deter birds from windows

cannot be overstated. Existing products and strategies, while

developed for other purposes, have great bird-safe potential

and have, in some cases, been used intentionally as such.

Still there remain few materials specifically developed for this

purpose as industry demands have not pushed manufacturers to

meaningful action. It is hoped that ongoing research along with

collaboration between architects, glass/film manufacturers and

bird conservation professionals will yield new products in the

near future.

Ornilux Glass (left) is currently the only commercially available

glass product being marketed as “bird-friendly.” A UV striped

pattern on the inside of the glass increases glass visibility for

birds while remaining relatively unobtrusive for people.

Many consider UV coated glass and films to be an ideal solution

because of their potential to deter birds while leaving the

appearance of glass largely unchanged. Recent research by

Dr. Daniel Klem of Muhlenberg College explored the use of

a window film with alternating UV reflecting and absorbing

stripes and found it highly effective as a deterrent to collisions.

22

Ongoing work in Austria by Martin Roessler has focused on

finding which patterns, when applied to glass, are most effective

in deterring birds while simultaneously requiring the least

coverage.

23

In the end, the development of effective bird-friendly products

requires the will on the part of building designers, owners

and managers to demand and test new and existing materials

in real-life conditions. A number of inspiring case studies

exist (see pages 32-36) and ongoing work with glass and film

manufacturers may soon yield readily available products that

satisfy both birds and people.

CHRISTINE SHEPPARD

24 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Lighting Design

Objective:

Undertake strategies

to reduce light trespass

from buildings,

particularly during

migration seasons.

REDUCING EXTERIOR BUILDING AND SITE LIGHTING has been proven effective at reducing nighttime migratory bird

collisions and mortality. At the same time, such measures reduce building energy costs and decrease air and light pollution. These guidelines

encourage efficient design of lighting systems as well as operational strategies to reduce light trespass from buildings, particularly during

migration seasons.

CONSIDER EXTEROR LIGHT TRESPASS

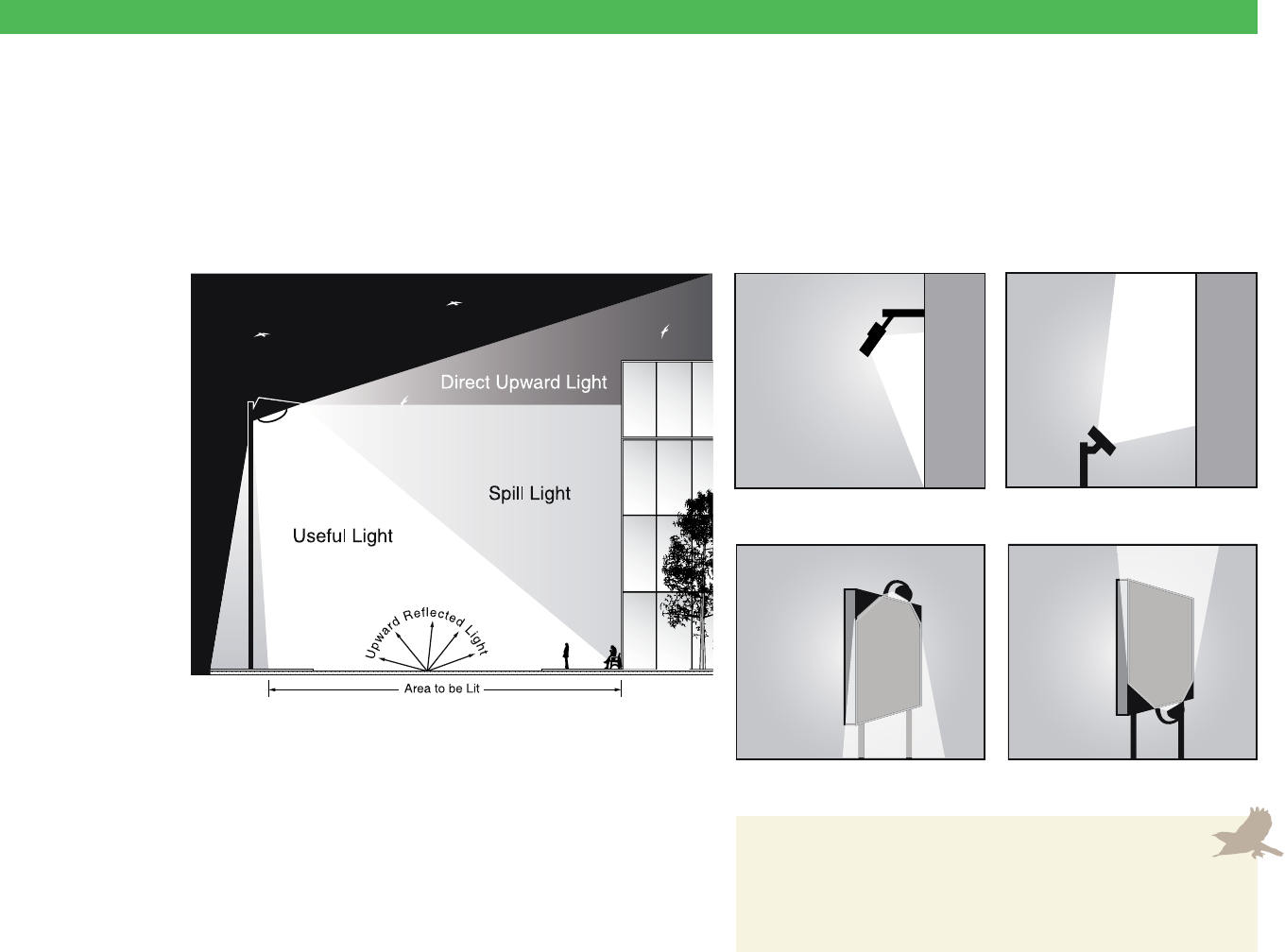

PREFERRED DISCOURAGED

Light pollution is largely a result of inefficient exterior lighting.

Eliminate light directed upwards by attaching cutoff shields to street-

lights and external lights.

Highlight building features without up-lighting.

Reduce the amount of light that spills outside areas where it is needed

for safety and security.

Maximize the useful light directed to targeted areas.

Eliminate the use of spotlights and searchlights during bird migration.

DID YOU KNOW?

Red lights that don’t flash are most attractive (and therefore

deadly) to birds. Instead, use flashing white or non-flashing blue or

green lights.

24

Direct exterior lighting downwards and adhere to Lights Out Guidelines

Light advertising from above to reduce the light projected skyward

Lighting diagrams courtesy

of the City of Toronto

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 25

CONSIDER INTERIOR LIGHT TRESPASS

Light trespass from within buildings can be reduced through design and

operational changes.

Design lights to shut off using automatic controls, including photo-

sensors, infrared and motion detectors. These devices generally pay for

themselves in energy savings within one year.

Reduce the need for extensive overhead lighting.

Encourage the use of localized task lighting and shades.

Reduce perimeter lighting and/or draw shades wherever possible.

PREFERRED DISCOURAGED

Preferred lighting designs project

light downward, reducing waste

and light pollution.

Discouraged lighting designs cause

spill light to be directed into the

sky where it is not needed.

LEED

WASTED LIGHT

Light pollution is

largely the result of

bad lighting design,

which allows artificial

light to shine outward

and upward into the

sky, where it’s not

wanted, instead of

focusing it downward,

where it is.

National Geographic,

November 2008

Coordinate with LEED Credits

SS 8.0 Light Pollution Reduction

EQ 6.1 Controllability of Systems: Lighting

EA 1 Optimize Energy Performance

26 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Building Operations

Objective:

Further reduce light

trespass through

operational procedures.

Implement monitoring

programs to determine

bird-collision areas

and success of light

reduction.

GREAT STRIDES CAN BE MADE to reduce light pollution from buildings during normal building operations. These strategies

apply to new and existing buildings and often require the commitment and participation of both building owners and users. In addition,

implementing bird-collision monitoring practices will help identify problem areas of a building or site.

CONSIDER DAYTIME CLEANING

CONSIDER LIGHTS OUT

CONSIDER BIRD MONITORING

Cleaning during normal work

hours is becoming more common

and can reduce bird mortality and

light pollution. Such a schedule

reduces energy consumption

and enhances security. If cleaning

during the day is not an option:

Complete nightly maintenance

activities before midnight or

earlier.

Instruct cleaning crews to work

down from the upper stories,

turning off lights as they go.

Implementing daily bird-collision

monitoring provides valuable

information for science and for

prioritizing building retrofits.

Sweep the building perimeter,

setbacks, and roof daily for

injured or dead birds.

Note specific times, dates and

locations of birds that are found.

Work with Project BirdSafe to

document all bird deaths and

assist injured birds. Most birds

are protected by the Migratory

Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

Lights Out programs are city or state-wide initiatives designed to

reduce light pollution and bird mortality. In Minnesota, Lights Out

is coordinated by Audubon Minnesota’s Project BirdSafe using these

parameters:

Building owners and facility managers extinguish all unnecessary

exterior and interior lights from at least midnight to dawn especially

during bird migration periods:

(Spring) March 15 to May 31

(Fall) April 15 to August 31

Priority lights include: exterior architectural lighting; interior lighting

especially on upper floors; lobby and atrium lighting.

Clean buildings from the top down The iconic Wells Fargo building was the first to sign on to Lights Out in Minnesota

Bird monitoring pinpoints problem areas

NYC AUDUBONNYC AUDUBON

It is also recommended that building managers work with Project

BirdSafe to monitor the effectiveness of Lights Out programs by

tracking bird collisions and mortality rates. In addition, tracking light

emission reductions and cost savings can provide valuable statistics.

Sign on to Lights Out at mn.audubon.org

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 27

Comprehensive Site Strategy

Blue-winged Warbler

The overall rate of collisions at a given building is based on

many variables. Solutions can be implemented at the initial

design stage or with modifications or operational changes.

The following examples represent a comprehensive bird-

friendly site strategy.

A. Treatment applied to glass projecting visual markers to

make it visible to birds

B. Task lighting in use after dark

C. Blinds drawn after dark

D. Lights off after work hours

E. Awning blocks reflections on lobby windows from above

F. Glass effectively angled to reduce strike angle and project

reflections downward

G. Bird-friendly site ventilation grates

H. Use of lighting fixtures effectively projecting light

downward

MIKE LENTZ

28 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Modifications to Existing Buildings

Objective:

Undertake alterations

or retrofits to buildings

with high incidence of

bird collisions.

IMPLEMENTING BIRD-SAFE STRATEGIES for new buildings

provides important opportunities to protect birds through design.

However, new buildings represent only a small fraction of those

responsible for bird fatalities. Retrofitting existing buildings is an

important challenge and opportunity to help reduce bird-building

collisions. Systematic site analysis and bird monitoring can dictate

priorities for building modifications, programmatic enhancements

and landscape adjustments to benefit birds.

CONSIDER YOUR BUILDING AND SITE

This checklist summarizes conditions that contribute to bird injury and

mortality. It may be used towards an initial evaluation of new and existing

buildings for potential problems.

Region

Within Migratory Route

Proximate to Migratory Stopover Destination

Locale

Near Attractive Habitat Areas

Dense Urban Context (Reduced Sky Visibility)

Fog-Prone Area

Site

Nearby Trees and Shrubs

Adjacent to Grassy Meadows

Water Features/Wetlands

Façade Glass Coverage (Overall Percentage)

Less than 20%

Between 20 and 35%

Between 35 and 50%

Over 50%

Special Features

Unbroken Glass Expanses at Lower Levels

Courtyard(s)

Transparent Corners

Glazed Passageways

Glazed Site Dividers/Bus Shelters

Glazing Characteristics

Tinted

Reflective

Mirrored

Dusk and Night-Time Illumination

External Facade Up-Lighting

Non-Cut-Off Exterior Lighting

Spill of Interior Lighting

Other Building Elements

Antennae

Spires

Guy-Wires

LEED

Coordinate with LEED Credits

EQ 8.1 & 8.2 Daylight & Views

EA 1 Optimize Energy Performance

Specific bird-collision problem areas can be identified and targeted for

intervention during routine building maintenance activities.

Analyze your building facility and site to determine the presence and

extent of bird collision hazards. Use checklist at right.

Integrate bird monitoring efforts with daily maintenance. See “Bird

Monitoring” page 26.

Undertake retrofits and other strategies to reduce bird collisions.

Continue monitoring building(s) to determine the effectiveness of

retrofits in reducing or eliminating bird mortality.

Identify problem areas

CHECKLIST OF BIRD COLLISION LIABILITIES

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 29

CONSIDER MODIFICATIONS

Create a physical barrier at notably hazardous windows to deter birds

or reduce the momentum of their impact.

Install netting over problem windows.

Mount exterior coverings or insect screens.

Incorporate latticework, artwork, shading or shielding devices outside

glass.

Make interior changes to indicate glass barrier or remove attractants.

Install and operate window blinds, shades, or curtains to hide interior

views of plants and hiding places.

Close curtains or blinds after dark if the interior is illuminated.

Relocate or shield interior plantings, water sources, and other features

that may be contributing to bird collisions.

Install artwork or screening just inside glass to be clearly visible from

outside at all angles.

Retrofit problematic windows and facades which cause birds to

attempt to fly through glass or fly to reflections of habitat or sky. While

creating visual barriers for birds, these strategies can simultaneously

improve daylighting, save on energy costs, and enhance aesthetics.

Install transparent or perforated patterned, non-reflective window films

that make glass visible to birds.

Consider painting, etching or temporarily coating collision prone

windows to make them visible to birds.

Add decorative exterior screening and/or solar shading devices,

including louvers, awnings, sunshades, and light shelves.

Consider re-glazing existing windows that experience high rates of bird

collisions with translucent, etched, frosted, or fritted glass.

Consider replacing large existing windows with multiple smaller units,

divided lights, translucent, or opaque sections.

Window film eliminated collisions in this courtyard at Patuxent Refuge in Maryland Window screening by Birdscreen installed at Rowe Audubon Sanctuary in Nebraska

If monitoring reveals bird collisions, building retrofits usually focus on eliminating reflections and fly-through effects or creating physical barriers.

Many design strategies for new buildings and building operational changes (pages 16-26) can be used to improve existing buildings for birds.

NYC AUDUBON

LAURA ERICKSON

30 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

BEST PRACTICES FOR BIRD SAFETY

Creative use of graphics can serve program needs and simultaneously

create glazing opacity.

Utilize decorative window films and banners to announce programs,

enhance aesthetics, and display artwork.

Consider rotating art displays in problematic windows during each

migration season or on a more permanent basis. Such displays should

create enough visual noise to be seen clearly from outside the glass at

all angles.

Research public art programs in your area as a way of encouraging

window art displays.

CONSIDER OPERATIONAL CHANGES

In addition to incorporating bird monitoring with routine maintenance

and security operations, an existing building that is experiencing bird

collisions can consider other operational changes.

Institute the practice of cleaning during the day to reduce light pollution

and energy consumption, enhance security, and save money.

Educate building users about the dangers of light trespass for birds.

Incorporate lighting design changes to reduce spill light and automate

lighting systems.

Adopt a Lights Out policy for building and site.

Utilize minimum wattage fixtures to achieve required lighting levels.

CONSIDER LANDSCAPE ENHANCEMENTS

Generally the most effective way to solve bird-collision issues is by

dealing with reflective or transparent glass issues as outlined on pages

20-21. Sometimes, it is possible to alter landscaping to improve bird

safety at specific sites.

Consider moving or shielding habitat that is being reflected in windows

or is a lure from the other side of clear glass (fly-through effect).

To address problematic glass windows, consider planting or re-locating

trees and shrubs close to the building within a maximum of three feet.

This planting strategy can block access to habitat reflections and birds

alighting in these trees will not have the distance to build momentum

on a flight path towards the glass. Such plantings can also provide

beneficial summertime shading and reduce cooling loads.

Create a green screen for foliage to grow adjacent to building exterior

offering shading and visibility to birds.

See “Site and Landscape Design” pages 16-17.

Dayshift cleaning

cost savings are

estimated at 4-8% per

year. That translates

to $145,790 –

$291,581 for a

building like the IDS

Center in Minneapolis

or up to $10 million

a year if incorporated

throughout the city.

25

LEED

Coordinate with LEED Credits

SS 8.0 Light Pollution Reduction

EQ 6.1 Controllability of Systems: Lighting

SS 5.1 Protect or Restore Habitat

CONSIDER PROGRAMMATIC OPPORTUNITES

Community art displays, like this one at St. Paul Travelers, can reduce bird collisions

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 31

CONCLUSION

Hope for the Future

BIRDS HAVE CAPTURED OUR HEARTS throughout history.

We are captivated by their songs, their colors and their unlikely

feats of endurance during migration. Birds have penetrated our arts,

literature and even hijacked our leisure time. And birds are indicators

of the state of our world. We all have a stake in their future.

While the challenges we all face in protecting biodiversity seem

daunting, solutions abound. With commitment we can halt and

reverse the decline of birds and their habitats. Reducing hazards

to birds navigating our built environment is one way to make a

positive difference. Armed with the knowledge and best practices

included in these guidelines, we can incorporate bird-safe strategies

in our approach to new construction. And, with examples of other’s

successes, we can modify existing structures to reduce their toll on

birds. In either case we need to take action.

We have great potential in our urban centers to engage people – from

residents to community leaders, from students to executives – in

making changes that help us all co-exist with nature. Being “green”

is now a pervasive desire expressed in our product choices in the store,

our design choices in our buildings and in our guiding principles as

a culture. Incorporating the needs of birds is a logical progression in

our concept of sustainable design and development. Working across

disciplines using intellect and creativity can yield untold benefits for

people and for birds in the future.

Architects, designers and biologists working together are our best hope for the future

A polycarbonate core makes this glass visible to birds (IIT Student Center, IL) Warblers like this Chestnut-sided will benefit from our creativity and collaboration

NYC AUDUBON

LAURA ERICKSON

32 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

The Minneapolis Central Library incorporates bird-safe design

techniques in several ways. Its variegated and curtained facade presents

an identifiable pattern to birds, while an indigenous shale and birch

garden at the building’s north perimeter filters views to and from the

main level reading rooms. This technique of planting very close to a

building facade, in addition to providing shade, prevents incidents of

fatal bird strike. Birds cannot see reflections cast upon the glass and are

less likely to develop fatally high speed collision rates due to the close

proximity of planting to glass. The Library’s central atrium features

angled glass, a dramatic architectural feature that also greatly eliminates

reflections of habitat and sky from most angles. The likelihood of fatal

collisions at this angle is also greatly reduced.

MINNEAPOLIS CENTRAL LIBRARY - Minneapolis, MN

▪ Architects: Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects ▪ Landscape design: Coen + Partners ▪ Architectural Alliance

CASE STUDIES

New Construction

Solution: Visual

Noise

Solution: Vegetation

near building

Problem: Reflection

Problem:

Transparency

BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES 33

AQUA TOWER - Chicago, IL

▪ Architects: Studio Gang Architects

Solution: Screen /

scrim / fritting

Solution: Visual

Noise

Problem: Reflection

Problem:

Transparency

The Aqua Tower is a new Chicago landmark and the winner of the 2009

Emporis Skyscraper Award for high-rise architecture. This 82-story

residential and commercial tower is a departure from the modern

sheer glass skyscraper, incorporating an undulating pattern of exterior

terraces which create an organic façade. Architect Jeanne Gang and her

team not only aspired to create the natural look of eroded cliffs with

the wavering terraces, they also convinced the developer to use fritted

glass with a grey dot pattern and picketed railings on the balconies, all to

enhance bird-safety. Gang has long been an advocate of bird-safe design

and has incorporated bird-safe strategies in a number of her projects.

studiogang.net

This renovation and 75,000 square foot addition to an existing science

facility was planned to create a series of outdoor courtyards that took

advantage of the site’s beneficial topography and mature trees. Sensitive

to the liabilities of extensive glazing placed near attractive landscapes,

the College and its architect consulted ornithologist Daniel Klem who

proposed patterning portions of the glass at potential collision “hot

spots.” After testing several configurations, the designers decided to use

a glass with a ceramic frit matrix at locations deemed susceptible to bird

collision. Swarthmore engineering professor Carr Everbach designed a

“thump sensor” webcam for installation next to windows to detect bird

collisions. According to Klem, collisions have been reduced significantly

to a mere one or two a year, giving Swarthmore confidence to extend

the treatment to other campus buildings.

archnewsnow.com/features/Feature171.htm

SWARTHMORE COLLEGE UNIFIED SCIENCE CENTER - Swathmore, PA

▪ Architects: Helfand Architecture and Einhorn Yaffee Prescott ▪ Landscape design: Gladnick Wright Salameda; ML Baird & Co.

STUDIO GANG ARCHITECTSBIRDSANDBUILDINGS.ORG

34 BIRD-SAFE BUILDING GUIDELINES

This Town building with reflective glass and a solarium entrance has

long been a site of bird strikes. The environment is one of six strategic

goals for Markham Council. One of the town Councilors, Valerie Burke,

championed bird-friendly buildings and design as an integral aspect of

the environment. Town staff worked with FLAP and The Convenience

Group to develop and apply a patterned window film to address the bird

collision problem.

This is the first application of a bird-friendly window film on a municipal

building in the Greater Toronto Area. Initial results indicate the film is

very effective in eliminating collisions. This application could serve as a

highly influential tool for convincing building managers and governments

at all levels to make their structures bird-friendly.

flap.org/markham.htm

TOWN OF MARKHAM – Markham, Ontario, Canada

▪ The Convenience Group ▪ The Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP)

Retrofitting Existing Buildings

This green building demonstration project, completed in 2001, was built

adjacent to a wetland. Its glazed elevations, while affording intimate

views of the natural surrounding, caused bird fatalities. The problem was

successfully remedied through a partial retrofit with fine netting.

CUSANO ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION CENTER – Philadelphia, PA - John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge

Solution: Use

of plastic films,

diachroic coatings

and tints on facade

Problem: Reflection

Solution: Screen /

scrim / fritting / net

Problem: Reflection

Problem:

Transparency

CASE STUDIES

FLAPBILL BUCHANAN