Front Cover

A COMMONWEALTH NORTH STUDY REPORT

Meera Kohler & Ethan Schutt, Co-Chairs

February, 2012

ENERGY FOR A

SUSTAINABLE ALASKA

The RuRal ConundRum

STATEWIDE ENERGY NEEDS

TO BE PRIORITIZED NOW

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

IN ALASkA TODAY, NEARLY 80% Of RURAL COMMUNITIES ARE DEPENDENT

ON DIESEL fUEL fOR THEIR PRIMARY ENERgY NEEDS. THE POOREST ALASkAN

HOUSEHOLDS SPEND UP TO 47% Of THEIR INCOME ON ENERgY, MORE THAN fIvE

TIMES THEIR URbAN NEIgHbORS.

Commonwealth North therefore recommends that Alaska:

Board of Directors

President - Michael Jungreis - Davis Wright Tremaine, LLP

President Elect - Tom Case - University of Alaska Anchorage

Secretary - Michele Brown - United Way of Anchorage

Treasurer - Meera Kohler - Alaska Village Electric Cooperative

Past President - Thomas Nighswander - Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium

Executive Director - Jim Egan

Editor and Program Director - Joshua Wilson

Nils Andreassen - Institute of the North

Don Bantz - Alaska Pacific University

Milt Byrd - President Emeritus, Charter College

Pat Dougherty - Anchorage Daily News

Joe Farrell - ConocoPhillips Alaska, Inc.

Cheryl Frasca - Municipality of Anchorage

Patrick Gamble - University of Alaska

Joe Griffith - EJ Griffith Enterprises

Max Hodel - Founding President,

Commonwealth North

Karen Hunt - Superior Court Judge, Retired

Bruce Lamoureux - Providence Health &

Services, Alaska

Marc Langland - Northrim Bank

Janie Leask - First Alaskans Institute

James Linxwiler - Guess and Rudd, P.C.

Jeff Lowenfels - Lewis & Lowenfels

David Marquez - NANA Development Corp

Jeff Pantages - Alaska Permanent Capital

Management

Mary Ann Pease - MAP Consulting, LLC

Morton Plumb - The Plumb Group

Governor Bill Sheffield - Founding Board

Member

Terry Smith - Carlile Transportation Systems

Jeff Staser - Staser Group, LLC

Tim Wiepking

Eric Wohlforth - Wohlforth, Johnson, Brecht,

Cartledge & Brooking

Jim Yarmon - Yarmon Investments, Inc.

Study Group Participants

Julie Anderson - Alyeska Pipeline Service

Ethan Berkowitz - Strategies 360

Chris Birch

George Cannelos - C. Cannelos & Associates

Greg Carr - Merrill Lynch

Del Conrad - Rural Alaska Fuel Services

Denali Daniels - Denali Commission

Mark Foster - Mark A Foster and Associates

Pat Galvin

Duane Heyman - Statewide Corporate Programs

Lonnie Jackson - Rural Energy Enterprises

Wilson Justin - Cheesh’na Tribal Council

Christine Klein - Calista Corporation

Mary Knopf - ECI/Hyer, Inc

Meera Kohler - Alaska Village Electric Co-op

Kaye Laughlin - The Laughlin Company LLC

Marilyn Leland - Alaska Power Association

Katie Marquette - Strategies 360

Iris Matthews - Stellar Group

Kate McKeown - Alaska Conservation Alliance

Jason Meyer - Alaska Center for Energy and

Power

Michael Moora - PDC Harris Group LLC

Christian Muntean - Beyond Borders

Karthik Murugesan - USKH

Kirk Payne - Delta Western

Mary Ann Pease - MAP Consulting

James Posey - Municipal Light & Power

Colleen Richards - Linc Energy

Chris Rose - Renewable Energy Alaska Project

Debra Schnebel - Acacia Financial Group

Ethan Schutt - Cook Inlet Region, Inc

Tiel Smith - Bristol Bay Native Corporation

Jan Van Den Top

Christine West - The Business MD

Dean Westlake - NANA Regional Corporation

Michele White

Tim Wiepking

2

Table of Contents

Study Group Participants ................................................................................................................ 1

Study Group Meetings and Presentations ....................................................................................... 3

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4

Commonwealth North Study Group Findings ................................................................................ 6

The Rural Alaska Energy Crisis ..................................................................................................... 7

The Cost of Energy .................................................................................................................. 8

Power Cost Equalization Program: A Stop-Gap Measure .................................................... 11

Sustainable Energy Development in Rural Alaska ....................................................................... 12

Overcoming Barriers: Connecting Rural Alaska ................................................................... 12

Overcoming Barriers: Definitive Statewide Leadership ....................................................... 18

Overcoming Barriers: Sustainable Project Financing ........................................................... 22

Navigating Alaska’s Regulatory and Permitting Landscape ........................................................ 24

Rural Energy Regulatory Roadmap ...................................................................................... 25

Appendix ....................................................................................................................................... 26

Renewable and Alternative Energy Options ......................................................................... 27

Power Cost Equalization Program Legislative History ......................................................... 30

Glossary of Key Alaska Energy Regulators .......................................................................... 33

State of Alaska Regulators and Permitting Authorities ................................................ 33

Federal Regulators and Related National Agencies ..................................................... 37

3

Study Group Meetings and Presentations

Thursday, May 19 - Steve Colt, Associate Professor of Economics, ISER - Rural Alaska

Energy Expenditures/Rural Alaska Fuel Transportation and Logistics Costs

Friday, May 27 - Meera Kohler, President/CEO, Alaska Village Electric Co-op - A

Cooperative Approach to Locally Owned Electric Utilities

Thursday, June 2 - Sara Fisher-Goad, Executive Director - Alaska Energy Authority

(AEA) - Overview of AEA’s Rural and Alternative Energy Programs

Thursday, June 9 - Facilitated Discussion

Thursday, June 16 - Joel Neimeyer, Federal Co-Chair, Denali Commission & Denali

Daniels, Denali Commission

Thursday, June 23 - Melody Nibeck, Tribal Energy Program Manager, Bristol Bay Native

Association

Thursday, June 30 - Christine Klein, Chief Operating Officer, Calista Corporation &

Elaine Brown, North Star Gas

Thursday, July 7 - Aaron Schutt, Doyon Limited

Thursday, July 14 - Chris Lace, The Aleut Corporation and Bruce Wright, Senior Scientist

for the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association - Energy Solutions for the Aleutians - The A-

Team Approach to Energy Conservation, Bulk Fuel and Renewable Projects

Thursday, July 21 - Jay Hermanson, Director of Energy and Technical Services, NANA

Pacific - Project Manager of Denali Commission/NANA Transmission Study, “Distributing

Alaska’s Power - A Technical and Policy Review of Electric Transmission in Alaska”

Thursday, July 28 - Bob Cox, Vice President Petroleum Distribution, Crowley - Petroleum

Transportation & Delivery: Understanding Petroleum Retail Rates in Rural Villages

Thursday, August 4 - Jimmy Ord, Alaska Housing Finance Corporation, Research &

Rural Development, Rural Energy and Housing Programs and Policy Issues

Thursday, August 11 - Facilitated Discussion

Thursday, August 18 - Facilitated Discussion

Thursday, August 25 - Facilitated Discussion

Thursday, September 1 - Rich Seifert Energy and Housing Specialist, UAF & Robert

Venables, Energy Coordinator for the Southeast Conference

Thursday, September 8 - Doug Ott, Project Manager Hydroelectric Programs, AEA, &

Kat Keith Wind Diesel Coordinator

Thursday, September 15 - Harold Heinze, CEO, Alaska Natural Gas Development

Authority

Thursday, September 22 - Facilitated Discussion

Thursday, October 6 - Facilitated Discussion

Wednesday, November 2 - Facilitated Discussion

4

Executive Summary

The hallmark of a healthy, sustainable community is the availability of reliable and affordable

energy. Affordable energy remains unavailable in virtually all of rural Alaska and as a result

Alaska’s rural and indigenous communities are at severe risk.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the poorest households in rural Alaska spent up to 47% of

their income on energy in 2008, more than five times their Anchorage neighbor. Given the

meteoric rise in the cost of oil since then, estimates of the burden today are significantly higher.

The Commonwealth North Rural and Alterative Energy Study Group received presentations

from regional organizations on energy plans in various stages of developments. Virtually all the

plans included some version of renewable energy - generally still in the early concept design

stage - and interconnection of communities to that generation source. All the plans appeared to

be very high cost, upward of $500 million per region, and none would dramatically lower the

cost of energy without massive government subsidies.

The Renewable Energy Fund, established in 2008, is authorized to underwrite $250-300 million

of energy projects, but with projects for small communities coming in at $4-5 million each, it is

likely that per-community renewable solutions will cost $2 billion statewide, and will at best

keep electricity prices stable into the future. Heat and transportation fuel substitutions will

greatly increase this number.

This study identifies barriers to electric energy development and offers solutions to overcome

those obstacles. Ultimately, this study proposes that Alaska’s energy challenge must be tackled

in a holistic manner with the development and adoption by the Legislature of an energy plan that

systematically addresses these barriers and enables the implementation of solutions to overcome

them.

Map of Alaska courtesy of the Renewable Energy Alaska Project

5

The State of Alaska must acknowledge that energy infrastructure is the essential element of

public infrastructure. Absent a viable energy system, all other public infrastructure fails. Schools,

public health facilities, water and waste-water systems, airports, public buildings, and all other

major attributes of civilized society cannot exist for long without reliable, affordable energy.

Investments in these other assets are at risk in today’s economic environment and Alaska’s

citizens accordingly face risks as well.

As the state considers the investment of billions of public dollars in gas pipelines, hydro projects,

transmission lines, and other assets to serve urban areas, in effect buying down the true cost of

energy for urban Alaskans, it must also consider rural Alaskans. The state must recognize that it

is no longer practical to expect complex energy systems to be competently operated and

managed in small rural communities and instead must adopt regional planning to best serve

Alaskans. Investments in energy efficiencies, hybrid systems to incorporate renewable energies,

and transmission grid development all reduce the overall cost to the State and individual

Alaskans overtime. Energy infrastructure is a critical area for the State of Alaska, regional

organizations, and communities to partner and invest.

This means adopting values that shift to a cohesive view of Alaska energy sustainability that

serves all Alaskans similarly irrespective of the political powers at federal, state and local levels

that at times can reflect geographic priorities versus a longstanding policy for all Alaskans.

Regional focus, structure, and identity may vary, however the overarching objective to provide

reliable and affordable energy to all Alaskans should remain constant throughout.

6

Commonwealth North Study Group Findings

1. Alaska needs a statewide energy vision, plan, and implementation strategy that incorporates

a holistic view of statewide energy sustainability which serves all Alaskans similarly

2. The interconnection of rural communities into regional electrical transmission grids

develops economies of scale, creates efficiencies, reduces redundant infrastructure costs,

and develops a greater potential for alternative energy projects

3. In order to mitigate the high cost of energy in rural Alaska, dependency on diesel

consumption must be reduced through increased efficiencies and utilization of

economically viable alternatives

4. A single statewide entity could coordinate energy generation and transmission project

selection and advocate for all regions of the state in a balanced fashion

5. The State of Alaska could ensure high-value and effective investments in energy projects

through:

Creating of an investment structure that can serve as an aggregator of financing for

energy projects

Requirement of equal competition amongst funding opportunities across all energy

sectors and technologies in order to reduce the cost of energy

Designing and auditing programs to ensure that experienced teams are making

accountable procurement decisions

Securing long term sustainability of funding by transitioning away from grants and

toward other financing options

Providing a “one stop shop” to deal with all permitting regarding energy projects and

to assist with information and assistance in working with federal regulators

6. Alaska should strive to eliminate the need for the Power Cost Equalization Program (PCE)

by reducing the electric rates paid by rural consumers to levels comparable to those paid by

consumers on the Railbelt

The Regulatory Commission of Alaska should ensure electric utilities that participate

in PCE are implementing cost effective energy conservation measures and feasible

alternatives to diesel generation in accordance with Alaska Statute 42.45.130

7

The Rural Alaska Energy Crisis

Twenty percent of Alaska’s 710,000 residents live in almost 300 communities spread across

500,000 square miles. While some rural communities are larger - Ketchikan, Kodiak, etc. - most

are small. Hub communities such as Barrow, Bethel, Kotzebue, Nome, Dillingham and others are

home to 2,500-5,000 people while some 250 communities have populations of 50-1,100. Per

capita income is extremely low while costs of goods and services are extremely high. Low

income and high costs are among the drivers causing many community members to move to

hubs, urban communities, and outside destinations in search of gainful employment and

affordable cost of living.

Electricity first appeared in rural villages as a result of resource development and economic

opportunities. In the 1950s, electricity slowly made its way into more villages via small

generators for local schools. Availability of electricity became more widespread during the

1960s and by the mid-1970s most remote communities had central station diesel generation

facilities. The demand for petroleum products continued to rise as the use of outboard motors and

snowmachines became more prevalent.

Prior to the Arab oil embargo of the early

1970s, diesel fuel and gasoline were

available, even in the most remote Alaska

communities, for less than $1.00 a gallon.

When the commodity price rose dramatically

in the late 1970s, subsidy programs were

established to reduce the end cost of electricity. When state coffers grew flush with earnings

from the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, efforts were undertaken to assure long-term low-cost

electricity for urban areas of the state.

When solutions remained elusive for the vast majority of Alaska, Power Cost Equalization (PCE)

was enacted as a solution to keep electricity affordable for residents and public facilities. No

solutions were proposed for commercial users, or energy for heating and transportation needs.

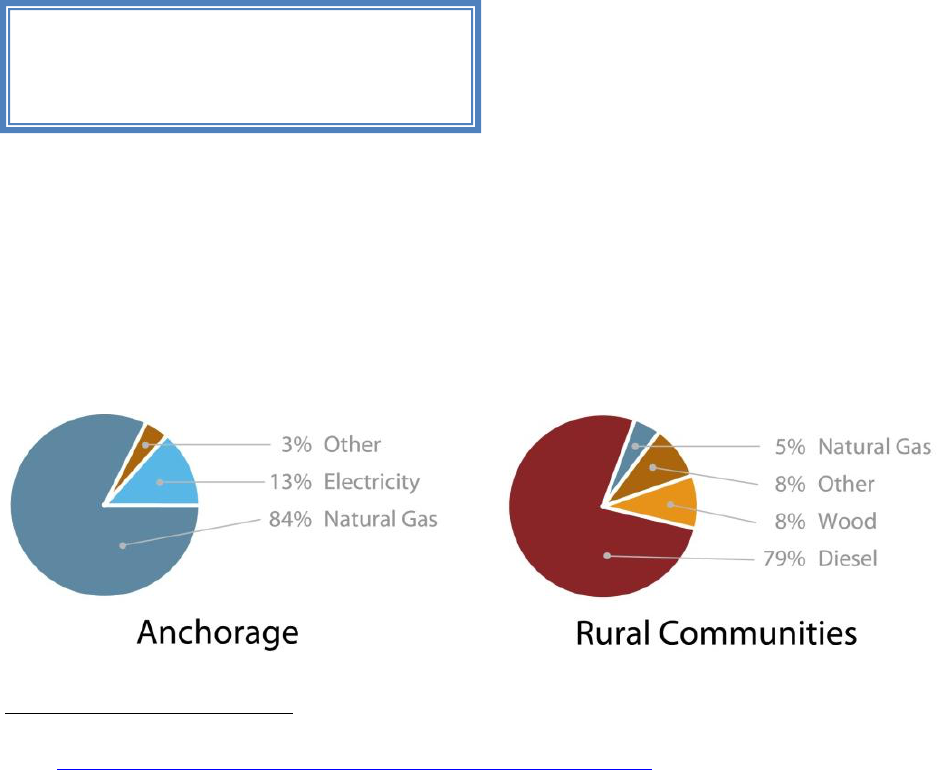

Figure 1 – How Alaskans Heat Their Buildings

1

1

Ben Saylor, Sharman Haley, & Nick Szymoniak, Estimated Household Costs For Home Energy Use (ISER, May

2008) www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/webnote/LLFuelcostupdatefinal.pdf

Today, nearly 80% of rural

communities are dependent on diesel

fuel for their primary energy needs.

8

Today, nearly 80% of rural communities are dependent on diesel fuel for their primary energy

needs. There are many factors that contribute to the high and rising cost of diesel. Transportation

is a major cost driver; how fuel is transferred (truck, barge, plane) and how far that fuel is

transported significantly contributes to total cost. The farther the community is from a hub the

greater the cost. Distance also increases costs by the number of times fuel is handled en route and

potential transport or handling difficulties, especially if barged on a shallow river or, flown into

communities. Year round or seasonal delivery affects cost and a lack of local infrastructure such

as local storage capacity, moorage and unloading equipment, and port landing facilities also add

costs.

Figure 2 – Trend in Average Alaska Fuel Prices

2

The Cost of Energy

Energy (electricity, heating fuel and diesel fuel) represents a very significant component of rural

Alaskans’ annual cash outlay, with the figure approaching or exceeding 40%.

3

In the last five

years the price of fuel in Alaska has grown dramatically, particularly affecting rural Alaska

where transportation costs are greater. While the State of Alaska does not have a well defined

energy plan, there have been recent efforts to develop such a plan. There are numerous regional

plans in various stages of development. Regional planning and leadership is a critical component

yet none of these plans offer comprehensive relief to the high cost of energy without heavy

reliance on significant state funding to buy down the cost of energy to an affordable level.

2

Alaska Department of Commerce and Economic Development Division of Community and Regional Affairs,

Research and Analysis Section, Current Community Conditions: Fuel Process Across Alaska (Aug 2011)

www.dced.state.ak.us/dca/pub/Fuel_Report_Jan_2011.pdf

3

Nick Szymoniak, Ginny Fay, Alejandra Villalobos Melendez, Justine Charon, & Mark Smith, Market Factors and

Characteristics Influencing Rural Alaska Fuel Prices (ISER, February 2010)

www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/webnote/LLFuelcostupdatefinal.pdf

$3.00

$3.50

$4.00

$4.50

$5.00

$5.50

$6.00

$6.50

Nov-05

Feb-06

May-06

Aug-06

Nov-06

Feb-07

May-07

Aug-07

Nov-07

Feb-08

May-08

Aug-08

Nov-08

Feb-09

May-09

Aug-09

Nov-09

Feb-10

May-10

Aug-10

Nov-10

Price per Gallon

Survey Date

Heating Fuel

Gasoline

9

Figure 3 outlines the estimated percentage of household income spent on home energy in a year

(2008). Remote households with the lowest incomes face the highest cost burden, estimated in

some cases to be 47% of their total income. Even rural households with higher incomes spend

nearly twice as much as Anchorage residents spend for energy.

Figure 3 – Estimated Median Share of Income Alaska Households Spend for Home

Energy Use

4

Because energy has been consistently expensive, people in rural places tend to use less than half

as much total energy as people with natural gas or hydro power as in Anchorage and Southeast

Alaska. In the Yukon-Kuskokwim Region energy is one of the major concerns for families due

to the high cost of diesel fuel that ranged from $6.14 to $9.50 per gallon in 2010. Many rural

Alaska families struggle to both heat their homes and feed themselves.

Figure 4 – Cost of Diesel Fuel in Selected Communities

5

4

Nick Szymoniak, Ginny Fay, Alejandra Villalobos Melendez, Justine Charon, & Mark Smith, Market Factors and

Characteristics Influencing Rural Alaska Fuel Prices (ISER, February 2010) “HH” Represents

Householdswww.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/webnote/LLFuelcostupdatefinal.pdf

5

Ginny Fay, Ben Saylor, Nick Szymoniak, Meghan Wilson, & Steve Colt, Study of the Components of Delivered

Fuel Costs in Alaska (ISER, January 2009) www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/fuelpricedeliveredupdate.pdf

10

Figure 5 – Gulf Coast & Interior Fuel and Gasoline Prices: On & Off the Road

System

6

Gulf Coast

On Road System

Off Road System

Interior

On Road System

Off Road System

Heating Fuel:

Heating Fuel:

High

$4.30

$6.86

High

$5.50

$10.00

Low

$4.19

$4.28

Low

$4.00

$4.34

Average

$4.24

$5.38

Average

$4.51

$6.27

Gasoline:

Gasoline:

High

$4.33

$7.07

High

$5.65

$10.00

Low

$4.22

$4.56

Low

$4.04

$5.30

Average

$4.29

$5.54

Average

$4.64

$6.67

Electricity in rural Alaska is delivered by a variety of service providers. Larger utilities like

Alaska Village Electric Cooperative (54 communities) and Alaska Power and Telephone (29

communities) serve more than half of Alaska’s village residents. Many communities receive

central station electricity from a locally owned private or municipal utility. Almost all use diesel

fuel for power generation. Electricity cost, $.58-$1.05 per kilowatt-hour, is very high. Even with

PCE offsetting the cost of up to 500 kWh for residential users most homes use less than 50

percent of the national average kWh consumption. Commercial users pay the full cost of

electricity. Those costs are passed on the consumers.

Figure 6 – Primary Energy Consumption Per Alaskan

(Barrels of Oil Per Person Per Year)

7

6

Alaska Department of Commerce and Economic Development Division of Community and Regional Affairs,

Research and Analysis Section, Current Community Conditions: Fuel Process Across Alaska (Aug 2011)

www.dced.state.ak.us/dca/pub/Fuel_Report_Jan_2011.pdf

7

Steve Colt, Fuel Costs, Community Viability, and Alaska Energy Policy Presentation (May 2011)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Alaska

Gas Network

PCE Areas

Other

Barrels of Oil per Year

Wood & All Others

Other Petroleum

Gasoline

Diesel

Hydro

Coal

Natural Gas

11

Power Cost Equalization Program: A Stop-Gap Measure

When the State of Alaska began receiving

revenues from the production of North Slope

crude oil in the late 1970s, the search began for

energy solutions to reduce the end cost of

electricity for all Alaskans. Although solutions

were identified for 85% of Alaskans, none

were forthcoming for rural Alaska.

PCE was established in 1984 as a parity program to lower the end cost of electricity in rural

Alaska while projects were built to lower costs in more urban areas – Bradley Lake Hydro to

serve the Railbelt, the Northern Intertie to bring low cost gas-fired power to Fairbanks, and

hydro projects to serve Valdez, Kodiak, Ketchikan, Petersburg and Wrangell.

PCE is computed for individual communities based on the local cost of service. The maximum

cost in FY10 was 81.59 cents and the average cost was 24.91 cents per kilowatt hour. PCE is

available only to residential accounts for the first 500 kWh and to community facilities (such as

street lights, water/sewer facilities and public buildings) for up to 70 kWh per resident per

month. Schools, commercial establishments, and federal or state government offices are not

eligible for PCE. Changes to the program since it was first enacted reduced eligibility by more

than 40%. Currently, about 30% of kWh sold in eligible communities receives PCE and the total

program cost represents 18% of the cost of electricity.

PCE is given directly to the end user in the form of a credit on their electric bill. The utility is

then reimbursed when it subsequently collects from the State of Alaska. It is not a funding

mechanism for system improvements. In the last 20 years, utility costs increased by 170%.

However, total PCE disbursed has only risen by 56%, highlighting the enormous burden being

borne by rural electricity consumers.

Retail electric rates in rural Alaska are as low as 15 cents a kWh (North Slope Borough villages

– subsidized by the North Slope Borough) and as high as 151 cents kWh (Lime Village) with the

average at around 50 cents a kWh. Larger communities’ rates are as low as 30 – 40 cents. Rates

in most communities average about 60 cents per kilowatt hour.

PCE is a stop-gap measure to make a basic amount of electricity affordable for rural residents.

Because PCE cannot reduce the cost of electricity for commercial users, high-cost energy

continues to be a major impediment to economic development and financial sustainability of

remote communities. When long-term energy solutions are established, the PCE Endowment

Fund (see appendix) can be dismantled and the subsidy program can be terminated.

Rural residents use less than half as

much total energy as people with

natural gas or hydro power as in

Anchorage and Southeast Alaska.

12

Sustainable Energy Development in Rural Alaska

Overcoming Barriers: Connecting Rural Alaska

As concerns mount over fuel prices, long-term energy availability, and climate change, attention

is turning toward one of the most pervasive places where energy can be conserved: the supply

chain associated with delivering fuel to rural Alaskan communities. The fuel supply chain is the

production and distribution network that encompasses the sourcing, transportation,

commercialization, distribution, and consumption of diesel fuel in rural Alaska. Roads and

transmission lines transport energy between communities. Efficient and strategic development of

infrastructure is important to decrease the capital, operations, and maintenance costs associated

with energy development in rural Alaska.

Figure 7 – Fuel Distribution Routes in Rural Alaska Markets

8

Most of rural Alaska communities are road-less and are not interconnected. Community isolation

has led to each community having unique and independent infrastructure including schools, rural

power systems, bulk fuel systems, airports, and rural health clinics. Each community’s

infrastructure has unique capital, operations, and maintenance requirements. This redundancy is

extremely costly to the State. For some of rural Alaska’s 250+ communities, the distance to the

8

Nick Szymoniak, Ginny Fay, Alejandra Villalobos Melendez, Justine Charon, & Mark Smith, Market Factors and

Characteristics Influencing Rural Alaska Fuel Prices (ISER Feb 2010)

www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/componenetsfuelsummaryfinal3.pdf

13

closest neighboring community is too

great to interconnect with either roads or

transmission lines. However, for many

communities interconnection can play a

critical role in reducing the capital

outlay of infrastructure and in

decreasing the cost of energy. With a

better understanding of the rural energy

supply chain and strategic development of critical infrastructure, inefficiencies can be identified

and strategies to overcome these inefficiencies developed. Strategically placed roads and

transmission lines are viable components to promote efficiencies in the rural Alaska energy

supply chain.

Technical Barriers (Providing Reliable Energy)

Commercially available technology can be widely deployed to

provide reliable energy solutions to rural communities

throughout Alaska. Many of the energy challenges outlined in

this report, given infinite levels of money and political will,

could be overcome yet sustainable energy solutions must be

financeable and ensure reliable and affordable energy for

Alaskans that is a challenge for many potential projects.

Integration – Successful integration of many renewable

energy sources with base electrical generation into village-

scale grids is a significant challenge. In particular, the

integration of intermittent renewable energy sources such as

wind and solar is an issue. Although headway has been made

to address this issue, barriers remain especially as the

complexity of the systems increase with higher penetration

levels.

Integration multiple energy sources while addressing issues

such as seasonality, intermittence, and complicated controls and operations protocols is complex.

In Alaska, efforts have been focused on developing wind-diesel systems. These systems have

been successful at low and medium wind penetration levels, while high penetration utility

systems have not yet been successfully deployed.

9

Relevant to integration is the need to develop adequate energy storage for village-scale

decentralized grids. This technology is a critical component to successfully integrating multiple

9

“A system is considered to be a high penetration system when the amount of wind produced at any time versus the

total amount of energy produced is over 100%. Low penetration systems are those with less than 50% peak

instantaneous penetration and medium penetration systems have between 50%-100% of their energy being produced

from wind at any one time. Low and medium penetration systems are mature technologies.” Denali Commission

Emerging Energy Technology Grant, Final Project Descriptions www.denali.gov

Photo courtesy of Alaska Housing Finance Corporation

Strategically placed roads and

transmission lines can play an important

role in decreasing the capital, operations,

and maintenance costs associated with

energy development in rural Alaska.

14

energy sources, specifically, those intermittent or seasonal renewable energy resources. Storage

technologies range over application (short, medium, and long term), and across technology types

(chemical, reservoir, mechanical, and thermal). There has been significant recent progress in

battery technology; however, there is currently no cost effective solution to address this barrier in

rural Alaska.

Operations and Maintenance – A corresponding issue arising with complex energy systems is

the need for sophisticated operations and maintenance. This barrier is broad and encompasses

such things as adequate human capacity both statewide and locally, the challenges associated

with operating such sophisticated systems in harsh, remote Alaskan conditions, and the limited

expertise, resources, and capital available globally for operating and maintaining these systems.

Space Heating – Many energy systems now are capable of addressing electricity generation

year-round, but addressing heating needs, particularly during winter months, remains a

challenge. Rural communities’ prime source of space heat generation today is from diesel and

fuel oils. While some communities have localized access to biomass resources, geothermal

resources, or even an overabundance of an electrical generation source such as traditional hydro

that could theoretically be used for heating, many communities lack a resource that could

technically address community heating needs, or the technology is not available to sufficiently

exploit the local resource.

Market Barriers (Providing Affordable Energy)

The significant barriers to

providing affordable energy to

isolated communities in rural

Alaska are market accessibility,

economies of scale, and the cost

of energy itself. These barriers

increase energy costs by limiting

economies of scale, increasing

cost of delivery, requiring

duplication of services, and

hindering access to more

efficient diesel and alternative

energy generation.

As discussed earlier, nearly all rural villages are dependent on diesel generation. Efficiency of

diesel generation is driven by generator size, with larger generators being more efficient, creating

more kilowatt-hours per gallon of diesel burned. Small communities typically require small

generation units. The small size of these communities results in less efficient generation,

increasing the cost of electricity.

Administration, maintenance and operations, capital expenditures, and availability of renewable

energy resources are all negatively impacted by community size and limited access. The

Photo courtesy of the Alaska Energy Authority

15

operating cost, excluding fuel, of a large generator versus a small generator is negligible. There

is little additional labor cost incurred by a large tank farm as compared to a small tank farm. The

administration costs related to reporting, managing, and ordering fuel are similar for small and

large utilities.

Market Accessibility – As most rural

communities are located in remote,

distant, or often difficult to access areas

this barrier is primarily a transportation

issue. The availability of convenient and

reliable transportation methods and the

access to transmission corridors help

reduce the cost of energy. Access

challenges not only affect the types of

energy solutions that can be implemented, but how they can be implemented. In terms of

reliability, this reduces available options, and in terms of affordability, makes projects more

expensive.

Economies of Scale – Similar to market access challenges, the economies of scale of the average

rural Alaska community pose a substantial barrier to leveraging sustainable and affordable

energy solutions. Many energy solutions require conditions where capital, operational, and

management costs can be distributed among a large user base and/or a large energy demand.

There are various methods currently being used to address this issue such as cooperative utility

ownership and fleet management, but all face challenges unique to isolated communities.

Cost of Energy – Finally, the high cost

of energy itself is a market barrier. It is

mentioned here because in terms of

economic development, long term

sustainability, and many other social

issues, this is a substantial market barrier

for rural Alaskan communities. Local

companies cannot afford to do business because the cost of energy is too prohibitive. Bringing

down the cost of energy will increase business activity in these remote regions and help promote

economic development throughout Alaska.

Interties in Rural Alaska

One way to mitigate the high costs driven by small community size and remote locations is to

connect communities by interties. The capital cost of a new small 1-1.2 megawatt power plant is

approximately $4-5 million dollars. Interties cost $250-400,000 dollars per mile. While the cost

of interties vary with distance, climate extremes, and geography the capital costs for interties are

generally less than duplicate generation plants for communities within ten to twenty miles of

each other. As more communities become connected, the benefits of higher efficiency generators

and operating economies become more pronounced.

As more communities become connected

through interties the benefits of higher

efficiency generators and operating

economies become more pronounced.

16

Current Southwest Alaska Communities

Potential Future Interties

Becoming A Grid

As an example, there are twelve

communities within roughly a twenty five

mile radius of Bethel. Interconnecting these

communities could significantly reduce the

cost of electricity in the surrounding villages

in the following ways:

Reduced Delivery Cost – Bethel is a

hub community with significant fuel

storage. By locating generation for

all the communities in Bethel, the

cost of reloading fuel into secondary

barges for delivery to smaller

communities would be eliminated

significantly reducing the cost of

diesel used for electric generation.

Higher Efficiency Generation –

While generation would need to be

maintained throughout the system for

emergency back-up, most generation

would be provided by large

generation plants located in Bethel.

Since the efficiency of diesel

generation is driven by generator

size, this would result in lower fuel

usage per kilowatt hour generated

and lower electric costs.

Better Access to Renewable Energy

– By linking villages with interties,

the opportunity exists to utilize

renewable energy sources. Larger

base loads will allow for greater use

of wind resources and communities

that have no access to renewable

energy can use resources available in

other locations. One potential

opportunity is to maximize

renewable energy by identifying the

ideal location for a resource such as

wind, and consolidating generation

in that location, thereby lowering

maintenance and operating costs by

centralizing expertise and equipment.

17

Creating interties between

communities has compelling

advantages and will play a

significant role in reducing electric

costs in rural communities.

Complicating the implementation

of even a partial rural grid is the

organization of electric generation

across communities. While some

villages are served by broad based

organizations such as AVEC and

Alaska Power and Telephone, many

more are independent, stand-alone

organizations. The structure of

these organizations varies from cooperatives to municipalities, tribes, and private corporations.

Integrating this disparate industry will require cooperation between communities, regulatory

agencies, and electric companies.

While interties cannot reduce energy costs for all communities in rural Alaska, the vast majority

would benefit from the development of connectivity. As village clusters begin to connect, the

advantages of connecting these clusters into an expanding grid will increase. The development of

regional energy grids will regionalize energy efficiency and allow for more economic energy

project decision making. The connection of regional grids into a statewide grid could

dramatically reduce the cost of energy in rural Alaska.

18

A Vision for a Connected Alaska

Diagrams courtesy of the Denali Commission

from their December 2008 intertie study entitled,

“Distributing Alaska’s Power: A technical and

policy review of electric transmission in Alaska.”

Development of rural interties

is an infrastructure investment

which fosters efficiency and

reduces redundancy. Interties

not only improve access to

reliable and affordable energy,

but also to health care and

educational opportunities.

19

Overcoming Barriers: Definitive Statewide Leadership

Alaskan have long battled for reliable and affordable energy. This is ironic because Alaska

boasts an abundance of hydrocarbons, as well as exceptional renewable energy resources such as

wind, tidal, hydro, geothermal, and biomass. Even more paradoxically, dusty shelves groan

beneath the weight of energy studies, energy plans, and energy task force reports. There are

clearly charted pathways forward, but inadequate progress taken down those paths.

Why, in the midst of plenty, do Alaska’s rural

communities pay the highest energy prices in

the nation? While there are technological,

financial, and regulatory obstacles that inhibit

the State and local communities’ ability to

make better use of these resources, structural

barriers have proven the greatest impediment to achieving greater energy independence, self-

sufficiency, and affordability. In spite of good intentions, Alaska lacks a clearly articulated

policy of mandates and metrics with strong, consistent, and institutional leadership to implement

and enforce energy policies and practices. Alaska has the resources to be a global energy leader,

but needs the right policy and structure in place. Without a plan, Alaskans cannot benefit from

the competition and innovation that are critical to resolving the State’s energy challenges.

Energy Needs Clear Direction: A State Energy Plan

While many tout the state’s aspirational goals, they do not carry the weight of clear policy

directives. The lack of a comprehensive state and regional energy policy is a significant factor in

the state’s inability to make meaningful and sustained progress towards affordable energy in

rural Alaska. Establishing a statewide energy policy will require leadership, commitment, and

buy-in from all stakeholders. This also means establishing and agreeing to a paradigm shift in the

current framework that treats Railbelt and rural communities separately and is typically highly

Photo courtesy of the Denali Commission

Why, in the midst of plenty, do

Alaska’s rural communities pay the

highest energy prices in the nation?

20

dependent on the political

hierarchy. A plan should include

the adoption of values that shift to

a more cohesive view of Alaska

energy as a package, serving all

Alaskans similarly irrespective of

the political powers at federal,

state and local levels.

This effort could be led by a nonpartisan stakeholder panel, similar to the House Energy

Committee stakeholder working group which convened in 2009 and ultimately recommended an

energy policy accepted by the Legislature in 2010. The energy policy was the first step toward

establishing long term objectives while de-politicizing energy decisions in Alaska. Optimally,

current elected leaders would establish such a group to provide input on the characteristics of a

state energy plan and use the input as the basis for legislation.

A starting point for establishing such a framework would be to identify shared values, common

interests, and mutual benefits. This could start at a statewide level and make its way to regional

energy planning, and ultimately to local decision making. A common framework for energy

decision making would provide consistency at all levels and chart the path for implementation.

Energy Needs A Champion: Centralized State Leadership

The lack of a powerful, institutional champion has caused Alaska’s energy development to drift,

and has resulted in fitful progress that is reflected in the costly subsidy and grant programs in use

today.

10

The state desperately needs agency leadership with the ability to coordinate energy

project selection, communicate and advocate for all regions of the state in a balanced fashion,

and take a leadership role in state government. Alaska Housing Finance Corporation (AHFC) is

the designated entity for receiving State Energy Program funding from the U.S. Department of

Energy. AHFC collaborates with the Alaska Energy Authority (AEA) through a Memorandum of

Agreement which outlines the relationship between the agencies and provides for the

coordination of activities. AHFC has successfully worked with AEA for many years with this

arrangement. Additionally AHFC has implemented successful end use energy efficiency

programs on its own. Energy resource development such as natural gas and oil production

activities are handled in other areas of state government, further compounding a lack of

consistency. Without a clear policy and a streamlined approach to overseeing all energy activities

in Alaska, one can understand the difficulty in making progress.

The State of Alaska should move to develop a statewide entity that coordinates energy

generation and transmission projects. Its purpose would be to generate, transmit, and sell

electricity to local electric distribution companies. One impact of such an organization is that

cost considerations would be evaluated on a broad regional basis, rather than on a community by

community basis. By changing the focus decision making regarding interties, renewable

10

These parallel subsidies include royalty free natural gas for the Railbelt and the PCE program for rural Alaska.

Alaska lacks a clearly articulated policy of

mandates and metrics with strong, consistent,

and institutional leadership to implement and

enforce energy policies and practices.

21

resources, and generation will be driven by financial results, improving efficiencies, and

lowering costs.

A statewide entity would oversee all facets of energy in Alaska consistent with the adopted

energy policy and vision. The following characteristics should also be considered:

Autonomy to execute statewide energy activities as established in an adopted energy plan.

Legislative actions should be consistent with the adopted energy plan and the oversight of

implementation should not be impeded by the political process.

Capacity to implement a policy would require a commitment of funding to assure

adequate staffing to carry out the vision and policy implementation. Critics of creating a

centralized state energy entity believe that creating more government is not the answer.

This new model would assure that existing structures are supported and streamlined.

Efficiency should be the main goal, while additional government and costs should be

avoided.

Regional leadership organization’s involvement is

integral in policy development and implementation.

Residents of the regions should have a voice

throughout the development process and

implementation. Existing processes should be

utilized when possible to further streamline and

coordinate development. In establishing the

implementation strategy, the identification of the

levels of responsibility should be carefully thought

through, vetted, documented, and monitored for efficiency. One guiding principle should

be the recognition that local involvement is core to any planning process and produces the

most sustainable results. Communication and efficient execution at local, regional, state,

and federal levels can be challenging, yet critical to executing an energy plan in a

consistent and cohesive way.

Energy Needs Consistency: Achieving a Vision

Energy development in Alaska is fragmented because decision making is scattered,

accountability cannot be assigned, and a great deal of money is used inefficiently. Sustainable

and affordable energy development requires economies of scale to justify large infrastructure

investments as well as a wide range of local energy solutions. This calls for a common, unifying

and compelling vision. This vision should be something that the recommended stakeholder panel

fully articulates, but should include:

An Alaska with the most energy efficient people in the nation

An Alaska which is a global leader in creating and exporting energy expertise and

technology, both in the clean use of hydrocarbons as well as renewable energies

An Alaska which is energy self-sufficient, supplying all of our own energy needs

An Alaska where every community has access to reliable and affordable energy

An Alaska that utilizes an efficient, smart, state-wide energy delivery system serving all

Alaskans equally

Regional and community

leadership are integral in

policy development and

implementation in order

to produce the most

sustainable results.

22

Overcoming Barriers: Sustainable Project Financing

Federal, state, and local governments,

and private sector investors have

invested billions of dollars in rural

Alaska energy projects and programs

over the past 40 years, yet rural

communities are still paying the highest

energy costs of anywhere in the nation.

Alaska should consider new

mechanisms and changes to the existing

structure that will ensure high-value and

effective investment in the future. The

State of Alaska must develop an

investment structure that clearly

articulates public sector program goals,

translates those goals into measurable

objectives, and assesses how well

programs have made progress toward those objectives. This is particularly important in light of

declining federal investment dollars. Alaska cannot expect the same level of federal funding it

has enjoyed in the past and so should take the following steps.

Create an investment structure that can serve as an aggregator of financing for energy

projects. This structure should be under the purview of the previously mentioned statewide

energy entity. Such an investment structure would provide services and benefits critical to

reducing the cost of energy to all Alaskans. Such an agency would take advantage of larger

economies of scale to aggregate community project costs. It would help local stakeholders with

minimal experience by providing administrative expertise for project development, collecting

and incorporating local input, coordinating bids when appropriate, operations, and reporting.

This additional structure would ensure accountability to investors and allow for additional

public/private investment opportunities.

Require equal competition among funding

opportunities across all energy sectors and

technologies in order to reduce the cost of

energy to the end user. Alaska’s energy

policy should be technology neutral seeking

the most cost effective and efficient options.

The current Alaska Energy Authority project selection process for the renewable energy fund is

competitive among projects, and should be driven by cost-effective investments rather than

technology categories. All energy requirements should be considered including heating,

electricity, and transportation fuels. There are cost effective projects such as increasing the

efficiency of rural diesel systems and using heat from diesel systems to displace fuel oil heating

which should also be considered.

Photo courtesy of the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation

Alaska’s energy policy should be

technology neutral seeking the most

cost effective and efficient options.

23

Design and audit programs to ensure that experienced teams are making accountable

procurement decisions. In the long term, government support programs such as grants or loans

will only be sustained and funded if they are effective and accountable in their uses of public

money. As a rule, the benefits of all state funds should accrue 100% to the benefit of the end

user. State government programs should not dissuade free enterprise private sector capital, but

rather should encourage and facilitate private sector investment whenever possible. Funding

decisions should be based on which projects have the greatest cost savings, community support,

and stable funding scheme in order to ensure projects completion

Ensure long term sustainability of funding by transitioning away from grants and toward

loans backed other financing options. Programs should shift to increase equity participation to

expand the availability and impact of limited government funding and increase private

participation and ownership, and improve loan repayment prospects. The Denali Commission

includes a process to review business plans of rural energy projects to ensure projects meet the

Denali Commission’s sustainability criteria. Many rural Alaska communities have submitted

requests for energy projects that are already in the queue waiting for federal funding that may not

be available. The project list and project requirements should be revised to reflect expectations

that local communities will have to increase their local contribution toward infrastructure in

order to be considered competitive in a more constricted federal grant funding environment.

Increasing local match requirements, which could include in-kind labor or resources if local cash

resources are not available will ensure local community buy-in, support, and project viability. It

should be noted, however, many existing electric utilities have little to no equity investment.

Incurring debt will add costs such as depreciation and debt service, which will likely increase the

retail cost of energy.

24

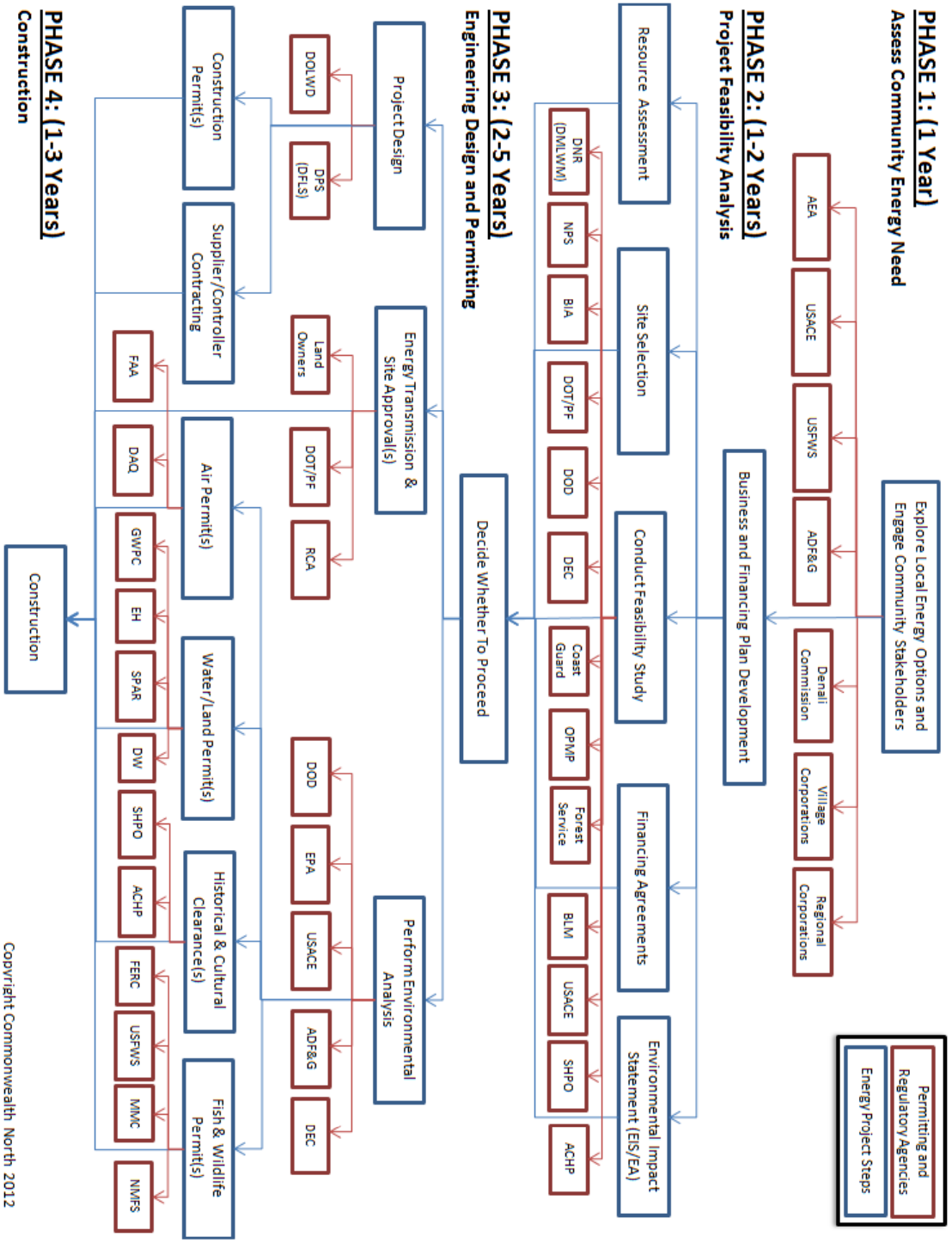

Navigating Alaska’s Regulatory and Permitting Landscape

Energy development in rural Alaska is regulated by numerous state and federal agencies. Each of

the following agencies outlined in the regulatory road map is involved in supporting, permitting,

and/or regulating energy projects in Alaska. Additionally local city and tribal governments,

Alaska Native Corporations, and public interest groups are also involved. These regulators are

important in ensuring the sustainable use of state and federal land, but together create an

extremely complex and difficult regulatory road to navigate. The following diagram outlines the

steps necessary to complete an energy project and the key state departments, federal agencies,

and national organization that impact energy generation and transmission in Alaska.

Rural energy projects are developed in four phases; (1) Outreach and Stakeholder Engagement,

(2) Project Feasibility Analysis, (3) Engineering Design and Permitting, (4) and Construction.

The first two phases are the most important in determining if a project is feasible and has

community support.

Converging on a set of solutions for complex problems, such as those encompassing the rural

Alaska energy challenges calls for a flexible, yet structured decision-making processes. The

complexity of this multi-dimensional challenge is a function of numerous drivers, including

technical, economic, cultural, regulatory and political components. Some of these drivers are

quantitative (e.g. technical or economic), while others are likely to remain qualitative, regardless

of the level of study devoted to understanding their behavior (e.g. cultural or political).

When a rural community is considering an energy project the local champions should begin by

exploring the available energy opinions and engaging potential stakeholder partners. Project

selection should ultimately include prescriptive methods for resource assessment followed by

ranking of energy alternatives based on fuel cost savings, efficiency gains, project capital and

operating costs, time to implementation, scalability/applicability to a variety of rural

communities, as well as environmental impacts.

As a community weighs its options, this project roadmap can act as a tool to better understand

the regulatory and permitting process and which state and federal agencies should be contacted at

each phase of the project. This is not an all inclusive list of project steps or regulatory agencies,

only a framework to better understand the regulatory and permitting process. Furthermore all

permitting should be completed in parallel to the financing and engineering tasks to shorten the

overall project timeline and help ensure project success.

25

Rural Alaska Regulatory and Permitting Roadmap

PHASE 1: Assess Community Energy Need (1 Year)

I. Explore Local Energy Options and Engage Community Stakeholders

PHASE 1: Regulatory/Permitting Agencies to Contact

Alaska Energy Authority (AEA)

US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

AK Dept. of Fish and Game (ADF&G)

Denali Commission

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

Regional Corporations

Village Corporations

PHASE 2: Project Feasibility Analysis (1-2 Years)

I. Business and Financing Plan Development

a. Resource Assessment

b. Site Selection

c. Conduct Feasibility Study

d. Financing Agreements

e. Environmental Impact Statement/ Environmental Assessment

II. Decide Whether to Proceed

PHASE 2: Regulatory/Permitting Agencies to Contact

AK Dept. of Environmental Conservation (DEC)

AK Division of Mining, Land and Water

Management (DMLWM)

AK Dept. of Transportation & Public Facilities

(DOT/PF)

Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP)

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

Coast Guard

Department of Defense (DOD)

Forest Service

National Parks Service (NPS)

Office of Project Management and Permitting

(OPMP)

State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO)

PHASE 3: Engineering Design and Permitting (2-5 Years)

I. Project Design

a. Construction Permit(s)

b. Supplier/Controller Contracting

II. Energy Transmission & Site Approval(s)

III. Perform Environmental Analysis

a. Air Permit(s)

b. Water/land Permit(s)

c. Historical & Cultural Clearance(s)

d. Fish & Wildlife Permit(s)

PHASE 3: Regulatory/Permitting Agencies to Contact

AK Dept. of Labor and Workforce Development

(DOLWD)

AK Dept. of Transportation & Public Facilities

AK Dept. of Fish and Game (ADF&G)

AK Dept. of Environmental Conservation (DEC)

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

Army Corp of Engineers (USACE)

Department of Defense (DOD)

Division of Air Quality (DAQ)

Division of Environmental Health (EH)

Division of Fire & Life Safety (DFLS)

Division of Spill Prevention & Response (SPAR)

Division of Water (DW)

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

Ground Water Protection Council (GWPC)

State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO)

Land Owners

Marine Mammals Commission (MMC)

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)

Regulatory Commission of Alaska (RCA)

PHASE 4: Construction (1-3 Years)

I. Construction

26

27

Appendix

Renewable and Alternative Energy Options

Although Alaska has vast identified energy options, they can be extremely difficult to harness

due to the high costs of materials, permitting, technology, transportation, limited accessibility,

daunting geology, and climate of many rural communities. Alaska has tremendous potential to

mitigate high energy costs and displace millions of gallons of diesel by using local renewable

and alternative energy resources. Here is a quick breakdown of the potential energy resources

available to some areas in rural Alaska.

Biomass – Biofuels in Alaska include timber,

sawmill wastes, fish byproducts, and municipal waste.

Most rural communities have access to at least one

form of biomass. The primary challenges are

harvesting and transporting biomass resources.

Abundant wood fuel at relatively low cost is the

primary way to promote savings by biomass energy

use. The highest savings are derived when wood fuel

is a byproduct of wood processing such as in the

creation of wood pellets for stoves.

Geothermal – Alaska has great geothermal

energy potential in the Interior hot springs, the

Southeast hot springs, the Wrangell Mountains, and

along the Aleutian chain. The heat generated by

natural hot springs and volcanoes can be used

directly or for electric production. Another potential

use is ground source heat pumps which use the

relatively constant surrounding earth or sea water

temperature to provide heating or cooling. The

primary challenge for geothermal energy in rural

Alaska is the remote location of geothermal resources relative to the population centers and

grids. Their remoteness is a significant impediment to develop and manage the resource in an

economic manner.

Hydroelectric – Hydroelectric energy offers

reliable base load power and generally delivers energy

at a stable price over a long period of time. Most

hydroelectric facilities have a potential life of 50-100

years. Alaska has been harnessing hydroelectric

energy since the late 1800s and it now supplies over

twenty percent of Alaskans’ energy needs. Although

hydroelectric power is widespread in certain regions

of the State, particularly Southeast Alaska, the

potential for even more hydro energy exists. Alaska

Bradley Lake Hydro Project

Chena Hot Springs Generators

Winter Heating Wood on Yukon River at Ruby

Photos courtesy of the Alaska Energy Authority

Corporation

28

has 40% of the United States’ untapped hydropower with an estimated 192 billion kWh energy

potential. There are around 99 indentified sites with a positive potential for future hydro

development in Alaska.

11

With 423 MW already installed in Alaska, hydropower is a mature,

proven technology that can greatly reduce the cost of energy.

Hydrokinetic – This energy resource is relatively new and

still in the pre-development stage, but has the potential to

provide a large amount of energy because of Alaska’s

extensive coastline and abundance of rivers. Alaska has one of

the best resources for tidal energy in the world, especially

along the Aleutian chain. Unfortunately, the sparsely populated

region has very low demand for energy. One of the better

prospects for wave energy is Yakutat, Alaska.

Natural Gas – Natural Gas is the cleanest fossil

fuel and is currently produced and consumed

throughout the State of Alaska. Though natural gas

does not have the same btu content as diesel it is a

much cheaper locally available natural resource.

Over 236 TCF of technically recoverable natural

gas has been identified on the North Slope. Cook

Inlet has also supplied Southcentral with gas for

many years and with a rejuvenated exploration

effort could potentially supply many parts of the

state with natural gas.

Propane – Propane can be utilized for home

heating, cooking, and fleet vehicles throughout

Alaska. Propane has the potential to serve many

rural communities which will never benefit from a

gas pipeline and provides an attractive clean

burning alternative to diesel. Propane is an

understood fuel source which is currently used in

many rural communities on a smaller scale. Alaska

North Slope propane resources have been estimated

to be between 40,000-80,000 barrels/day. Propane

is not a ground contaminant and has a carbon

footprint and emission levels which are far below

11

Alaska Energy Authority & Alaska Center for Energy and Power, Alaska Energy: A First Step Toward Energy

Independence (January 2009) www.akenergyauthority.org/PDF%20files/AK%20Energy%20Final.pdf

25 kW Turbine at Eagle

Exit Glacier Chalet

Conventional Gas Stove

Photo courtesy of the Denali Commission

29

diesel. Propane could be barged and trucked in to many of these communities the same way

diesel is today. The Institute of Social and Economic Research recently analyzed how propane

prices might compare to crude oil prices and estimated the price of propane delivered could be a

viable option.

12

Solar – Solar energy is an option though significantly

challenged by Alaska’s shortened solar cycle during the

winter months. Solar energy’s greatest potential is in

meeting small, low-powered off-grid energy needs. To

use solar energy effectively, energy storage is necessary

so that the acquired energy can be used over a longer

period of time. Most solar development in Alaska is in

remote areas for individual residences or services like

weather stations where the cost of alternative electrical

generation is extremely high. Utility-scale solar power

plants are uneconomical in Alaska with today’s

technology.

Wind – High velocity winds are standard in many parts of

Alaska and can be harnessed to mitigate diesel consumption.

Alaska’s best wind resources are found in the western and coastal

regions, but there are wind opportunities throughout the state. At

least 134 rural communities have a viable wind resource.

13

Wind

turbines use aerodynamic force to convert the wind’s kinetic

energy into mechanical energy. Wind energy can be used to

supplement diesel consumption, however wind is an intermittent

source of power and is only viable if there is already base load

generation or battery storage. Based on systems installed through

2009, more than $87 million has been invested in wind energy in

Alaska, at least $23 million of that by native corporations and

other private capital. Alaska now has over 13.1 MW of installed

wind capacity.

14

12

Ginny Fay & Tobias Schwoerer, Economic Feasibility of North Slope Propane Production and Distribution to

Select Alaska Communities (June 2010)

www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/Schwoerer_ay2010propane_phase2final.pdf

13

Alaska Energy Authority & Alaska Center for Energy and Power, Alaska Energy: A First Step Toward Energy

Independence (January 2009) www.akenergyauthority.org/PDF%20files/AK%20Energy%20Final.pdf

14

Alaska Center for Energy and Power, Wind-Diesel Applications Center www.uaf.edu/acep/alaska-wind-diesel-

applic/

Pillar Mt-Kodiak

Denali National Park

Photo courtesy of the Alaska Center for Energy and Power

Alaska has tremendous potential to mitigate

high energy costs and displace millions of

gallons of diesel by using local renewable

and alternative energy resources.

30

Power Cost Equalization Program Legislative History

The purpose of the PCE Program is to reduce the electric rates paid by rural consumers to levels

comparable to those paid by consumers in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau.

During the past thirty years, four different programs have subsidized rural electric rates:

Power Production Cost Assistance Program (PPCA) Fiscal Year 1981

Power Cost Assistance Program (PCA) Fiscal Year 1982 into Fiscal Year 1985

Power Cost Equalization Program (PCE) Fiscal Year 1985 into Fiscal Year 1994

Power Cost Equalization Fund and Rural Electric Capitalization Fund (PCE-REC) Fiscal

Year 1994 to Fiscal Year 1999

Power Cost Equalization Fund (PCE) Fiscal Year 1999 to Present

The five programs share some

common characteristics. Each

program reimbursed rural utilities a

percentage of their eligible costs

when those costs exceed entry rate,

now known as the floor. For example,

the first program, PPCA, reimbursed

85 percent of a utility’s costs in

excess of 7.65 cents/kWh to generate

and transmit electricity. Each

program also set a maximum ceiling

rate. In the case of the PPCA

program, the ceiling rate was 40

cents/kWh. Therefore, the PPCA program reimbursed a utility for 85 percent of its eligible costs

over 7.65 cents/kWh but below 40 cents/kWh.

When costs exceeded the ceiling rate of 40 cents/kWh, the initial PPCA program paid 100

percent of a utility’s excess costs. Subsequent programs differ from the PPCA program in that

they did not reimburse any costs beyond their ceiling rates. The first PPCA program also defined

eligible costs differently from the three subsequent programs. PPCA reimbursed a utility for

production and transmission costs but not for distribution and administration costs. The

subsequent programs permitted reimbursement for all of these costs.

The biggest difference between the initial and successor programs was the imposition of caps on

the costs eligible for reimbursement on a per customer basis. The initial PPCA program

reimbursed a utility for all of its eligible costs regardless of who consumed the electricity. All

three successor programs limited reimbursement to apply to only a certain amount of kilowatt

hours sold to each residential or commercial customer but made special provisions for

community facilities. For example, the PCA program reimbursed eligible costs for the first 600

kWh/month consumed by each residential or commercial customer. If a customer exceeded the

cap of 600 kWh/month, then they received no subsidy for amounts of electricity consumed in

excess of the 600 kWh/month.

Photo courtesy of the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation

31

The three successor programs treated community facilities in a manner distinct from the other

types of customers. Sales of electricity to community facilities qualified for a subsidy on the

basis of a set number of kilowatt hours per month per community resident. For example, the

PCA program reimbursed eligible costs for providing community facilities with electricity on the

basis of 55 kWh/month per resident. If a community had 100 residents, then the first 5,500 kWh

of electricity sold to the community facilities would qualify for the subsidy; conversely,

consumption above 5,500 kWh/month would receive no subsidy. The programs defined

community facilities as water and sewer facilities, public outdoor lighting, charitable educational

facilities, or community buildings whose operations were not paid for by the state, federal

government or private commercial interest.

The initial formula of the newest program, the PCE and Rural Electric Capitalization Fund,

varied from the formula of its immediate predecessor, the PCE Program, in two aspects. The

entry, or base rate, rose by one penny from 8.5 cents/kWh to 9.5 cents/kWh. The cap for

reimbursing eligible costs for residential and commercial consumptions also fell from 750

kWh/month to 700 kWh/month per customer.

In 1993, SB 106 established the PCE Fund, formerly known as the PCE and Rural Electric

Capitalization Fund, as a separate fund with an initial appropriation of $66.9 million with 3% of

the funds available for rural electric project grants. The following fund sources were established

for PCE:

$66.9 million appropriation to the newly created PCE fund

40% of future Four Dam Pool debt service – estimated to provide approximately $4.0

million per year for PCE

Interest earned on the unexpended balance in the PCE Fund

It also enacted limits on costs eligible for PCE during Fiscal Year 1994. During the state fiscal

year that began July 1, 1993, the power costs for which power cost equalization were paid to an

electric utility were limited to minimum power costs of more than 9.5 cents per kilowatt-hour

and less than 52.5 cents per kilowatt-hour. During each following state fiscal year, the

department must adjust the power costs for which power cost equalization may be paid to an

electric utility based on the weighted average retail residential rate in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and

Juneau.

In 1999, SB 157 enacted provisions that excluded previously eligible commercial customers

from participating in the program, and reduced the monthly cap of 700 kWh/month for

residential customers to 500 kWh/month. It also raised the “base” from the prior 9.5 cents/kWh

to 12 cents/kWh, effective 7/1/99. During each following state fiscal year, the power costs for

which power cost equalization may be paid to an electric utility will be based on the weighted

average retail residential rate in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau; however, the power costs

cannot be set lower than 12 cents per kWh.

This legislation also amended the PCE funding sources as follows:

The percentage of Four Dam Pool debt service allocated for PCE was increased from

40% to 60%. This 20% increment was previously allocated to the Power Project Fund

loan program.

32

Photo courtesy of the Denali Commission

The NPR-A special revenue fund was added as a potential source of PCE funding.

In 2008 in special session, when the price of crude oil hit $147 a barrel, the Legislature raised the

ceiling on allowable costs to $1.00 a kWh. This provision was set to expire on June 30, 2009 but

action was taken that year to set the ceiling at that level on a permanent basis going forward.

Power Cost Equalization Endowment Fund

In 2000, HB 446 established the

PCE Endowment Fund as a

separate fund of the Alaska Energy

Authority. The fund consists of;

(1) legislative appropriations to the

fund that are not designated for

annual expenditure for the purpose

of power cost equalization; (2)

accumulated earnings of the fund;

(3) gifts, bequests, contributions of

money and other assets, and

federal money given to the fund

that are not designated for annual

expenditure for power cost equalization; and (4) proceeds from the sale of the Four Dam Pool

power projects to the power purchasing utilities under a memorandum of understanding dated

April 11, 2000, between the Alaska Energy Authority and the purchasing utilities.

An initial appropriation of $100 million was made into the PCE Endowment Fund from the

Constitutional Budget Reserve. In addition, sale of the Four Dam Pool projects was finalized in

January 2002, which resulted in a deposit of approximately $84 million to the Fund.

The Endowment Fund is invested and managed by the Alaska Department of Revenue to earn

7%. 7% of the PCE Endowment Fund’s three year monthly average market values may be

appropriated to the PCE Rural Electric Capitalization Fund for annual PCE program costs. Most

of the funding needed to support the PCE program in future years is anticipated to come from

earnings of the Endowment Fund.

The PCE Endowment Fund was further capitalized with a General Fund appropriation of $182.7

million in October 2006, and $400 million in July 2011. The total invested assets of the fund as

of September 30, 2011 were $681,616,886, with the fund posting a year-to-date loss in 2011 of

just over $74,000,000.

33

Glossary of Key Alaska Energy Regulators

State of Alaska Regulators and Permitting Authorities

Alaska Railroad Corporation (ARRC)

Department of Commerce, Community & Economic Development (DCCED)

Alaska Energy Authority (AEA)

Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA)

Division of Economic Development

Regulatory Commission of Alaska (RCA)

Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC)

Division of Air Quality

Division of Environmental Health (EH)

Division of Spill Prevention and Response (SPAR)

Division of Water

Department of Fish and Game (DF&G)

Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development (DOLWD)

Alaska Occupational Safety and Health Program (AKOSH)

Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Alaska Coastal Management Program (ACMP)

Division of Forestry

Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys

Division of Mining, Land and Water Management

Office of Project Management and Permitting (OPMP)

State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO)

Department of Public Safety

The Division of Fire and Life Safety

Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT/PF)

Mental Health Trust Lands

University of Alaska Land Management

Alaska Railroad Corporation (ARRC) – If a project is being developed on Railroad lands or near

rail lines the Railroad must be consulted and agreements attained. The Alaska Railroad Corporation