University of South Carolina University of South Carolina

Scholar Commons Scholar Commons

Theses and Dissertations

2015

Foundations of Memory: Effects of Organizations on the Foundations of Memory: Effects of Organizations on the

Preservation and Interpretation of the Slave Forts and Castles of Preservation and Interpretation of the Slave Forts and Castles of

Ghana Ghana

Britney Danielle Ghee

University of South Carolina

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd

Part of the Public History Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Ghee, B. D.(2015).

Foundations of Memory: Effects of Organizations on the Preservation and

Interpretation of the Slave Forts and Castles of Ghana.

(Master's thesis). Retrieved from

https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3716

This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and

Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact

Foundations of Memory:

Effects of Organizations on the Preservation and Interpretation of the Slave Forts and

Castles of Ghana

By

Britney Danielle Ghee

Bachelor of Arts

Rice University, 2013

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Arts in

Public History

College of Arts and Sciences

University of South Carolina

2015

Accepted by:

Allison Marsh, Director of Thesis

Kenneth Kelly, Reader

Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies

ii

Acknowledgements

Without the constant support of those who have mentored me throughout my life, this

work would never have been written. For sparking my interest in the trans-Atlantic slave

trade I have to thank a young professor who was willing to offer a tutorial class when I

was the only student enrolled; Dr. Stephanie Camp was the spark that ignited my passion

and I am forever grateful for her commitment to my education. Dr. Allison Marsh has

been an amazing and energetic advisor, who always encouraged my writing style and

developed my museum philosophy, I am eternally grateful. Dr. Ken Kelly challenged my

writing, pushing me to place my argument into a larger conversation on memory and

anthropology, proving the importance of interdisciplinary collaborations. Without the

mental and editorial support of my roommate, Alyssa Constad, I fear that graduate school

would have left me humorless. And lastly to Sylvia Ming-Ghee and Heather Ghee, I

thank you for a lifetime of editing. Without the SPARC grant from the University of

South Carolina, it would have been impossible to gather my notes on tour narratives as

well as collect the images which will be used in the National Museum’s revision of their

current exhibition on the forts and castles.

iii

Abstract

The historical understanding of a place is bent to the will of the passage of time, but is

susceptible to the pressures of entities that lay claim to the space. The memory of forts

and castles dispersed along the tropical shorelines of Ghana have been remembered,

forgotten, and rediscovered several times over the span of five centuries. But how has

their story been changed? What is privileged and created for the collective memory and

what has been concealed? The buildings currently serve as memorials to the trans-

Atlantic slave trade, but this understanding is complicated by the previous preservation

motives and interpretations which impacted the interpretation, and therefore the

collective memory, of the forts and castles. Through an examination of the institutional

motivations, the changing political atmospheres, and the narratives crafted and told, the

evolution of the interpretation of the buildings from the emphasis on European

architectural deeply researched by the British colonial government, the post-colonial

stress on the Afro-European equitable trade, to transnational transformation of the

buildings into memorials to the trans-Atlantic slave trade can be determined. An

examination of the development of the narrative surrounding the buildings offers a long

history of the preservation of the forts and castles. But it also illuminates the interesting

ways interpretations created by twentieth century organizations charged with the

preservation of the buildings complicate the already complicated trans-Atlantic

interpretation of the forts and castles of Ghana.

iv

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ ii

Abstract .................................................................................................................................. iii

List of Figures ........................................................................................................................... v

List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................. vii

Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 2. The Colonial, Post-Colonial, and Global ............................................................. 6

Chapter 3. The Forts and Castles of Ghana ......................................................................... 10

Chapter 4. Model Architecture ............................................................................................. 24

Chapter 5. Pan-African Heritage and Identity Formations ................................................. 36

Creating Ghanaian ..................................................................................................... 37

Connecting African Diasporan ................................................................................. 47

Chapter 6. Conclusion ........................................................................................................... 60

Bibliography ........................................................................................................................... 65

v

List of Figures

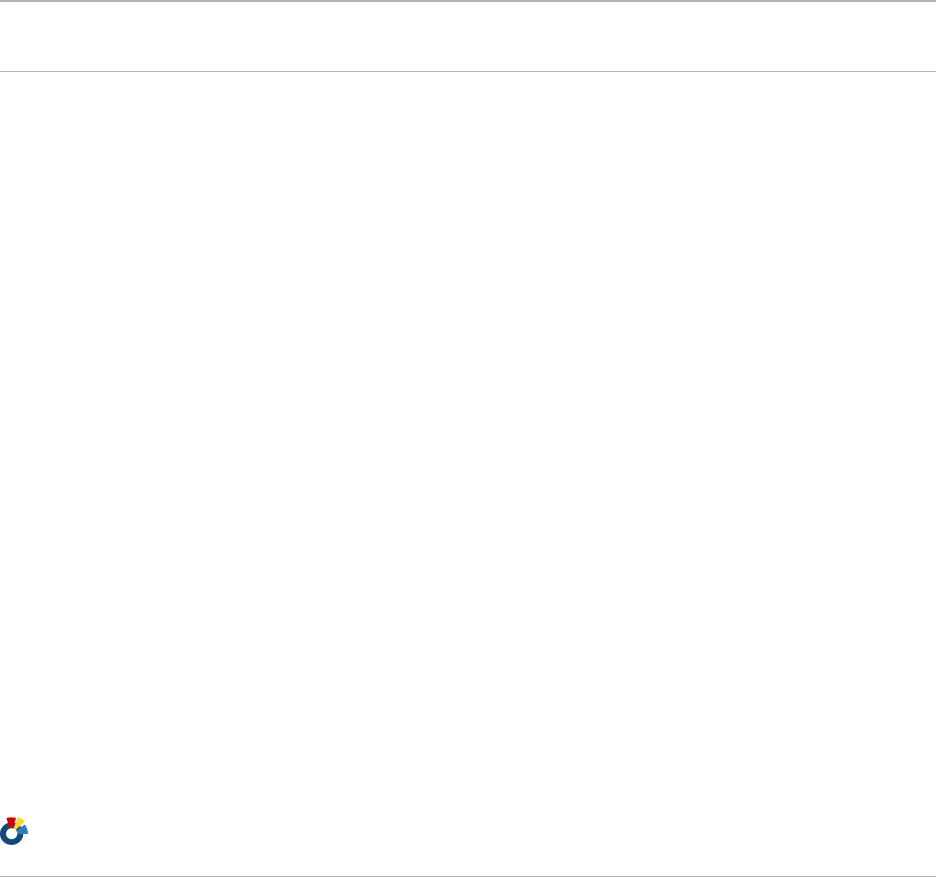

Figure 1.1 View of sea towards Elmina Castle from Cape Coast Castle .............................. 1

Figure 3.1 Map of extant forts and castle in Ghana ............................................................. 10

Figure 3.2 St. George’s (Elmina) Castle from Fort Saint Jago............................................ 13

Figure 3.3 Interior View of Cape Coast Castle ....................................................................15

Figure 3.4 Interior View of Fort Amsterdam........................................................................ 17

Figure 3.5 Remains of Fort Nassau ....................................................................................... 19

Figure 3.6 Africa Through a Lens Quarters, Fort Nassau, Moru ........................................ 19

Figure 3.7 Interior View of Fort William ............................................................................. 21

Figure 4.1 Interior View of Ft. Friedrichsburg ..................................................................... 25

Figure 4.2 Fort Keta’s Wall ................................................................................................... 27

Figure 4.3 Detailed Interior of Fort Amsterdam................................................................... 31

Figure 5.1 Male Dungeon Fort Prizenstein ........................................................................... 38

Figure 5.2 Doors of No Return ............................................................................................. 50

Figure 5.3 Elmina’s Female Dungeon .................................................................................. 56

vi

Figure 5.4 Door of No Return................................................................................................ 57

Figure 6.1 Fort Fredenshborg Ruins ..................................................................................... 64

vii

List of Abbreviations

GMMB ................................................................... Ghana Museums and Monuments Board

MOT ............................................................................................ Ministry of Tourism, Ghana

MRCGC .......................................... Monuments and Relics Commission of the Gold Coast

PWD .......................................................................... Public Works Department, Gold Coast

UNESCO ......................... United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

WHC ............................................................................................. World Heritage Committee

1

Chapter 1. Introduction

“Like the deadseeming cold rocks, I have memories within that came out of the material

that went to make me. Time and place have had their say.”

- Zora Neal Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

A warm, orange sun sets over the Gulf of Guinea as the silhouetted figures of

fishermen pull their painted canoes onto the sandy shoreline. The waves break one

hundred meters from the coast, yet nearby waves crash hard against a seemingly

impenetrable force overwhelming the serene scene. The building has stood the test of

time: existing across centuries, surviving military attacks, and lasting longer than any

one entity could control it. It is a source of both memory and forgetting - a physical

manifestation of a traumatic past that bears witness to its history. It disrupts the natural

shoreline, protruding out from its tropical surroundings; it is isolated, yet it does not

stand alone. More than twenty structures like it are dispersed across the coastline of

Ghana, connected to one another by their shared historical purpose and now their

monumental standing.

Figure 1.1 View of the sea towards Elmina Castle from Cape Coast Castle

Placed strategically on a cape, this castle was built by the Dutch just 13 kilometers from the

Portuguese castle nicknamed Elmina.

2

The status of the forts and castles of Ghana varies across time as their functions

develop and evolve according to official and collective memory; described by Alon

Confino as “who wants whom to remember what and why,” collective memory is

controlled by who owns that memory.

1

More than eighty forts and castles were

constructed on the Gold Coast’s sandy and rainforest covered shores across three

centuries by seven different European states beginning with the Portuguese construction

of Elmina Castle in 1482.

2

The castles, which were a large network of buildings opposed

to the smaller fort building classification, served as administrative, in addition to, trade

centers for the various European entities. Most fortifications changed hands as European

and Ghanaian states battled for control of the Gold Coast shoreline, all fighting for

dominion over trade. However, this is not a chronological survey of who owned what.

Rather, it is an analytical interpretation of the narrative surrounding these buildings that

examines the formation, mission, and interpretation of three twentieth century

organizations that claimed responsibility for the preservation of the historic buildings.

The forts and castles perfectly encapsulate Pierre Nora’s foundational interpretation of

lieux de mémoire because these buildings represent “a particular historical

moment…where consciousness of a break with the past is bound up with the sense that

memory has been torn…. in such a way as to pose the problem of the embodiment of

memory in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists.”

3

Their emergence

1

Although I prefer the terms slave fort, slave castle, or castle-dungeon, for the purpose of this paper the

buildings will be referred to with the official terminology of fort and castle so that historical emphasis is

not incorrectly placed. (Richardson 2005, 617) Alon Confino, “Memory and Cultural History: Problems of

Method.” The American Historical Review 102:2386-403.

2

Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Museum and Monuments Board, 1999)

10; Albert van Dantzig. Forts and Castles of Ghana. (Accra: Sedco, 1980) 3;Also note that at least one fort,

Ft. Ruychaver, was built inland on the Ankobra River (Ibid., 27).

3

Pierre Nora, Genevieve Fabre and Robert O’Meally, edit., “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de

Memoire,” History and Memory in African American Culture, Oxford: Oxford University 1994, 284.

3

as memorials to the transatlantic history is a result of their violent history, which typically

and “simultaneously destroys and creates history,” must be placed within trends of

globalization and the proliferation of heritage in order to understand the development of

their narrative.

4

Furthermore, the history of the forts and castle’s preservation must also

be examined in order for foundational interpretations to be examined.

The forts and castles discussed in this paper are no strangers to scholarly attention

and investigation. In fact, the earliest non-commercial survey of the forts and castles is

used as a primary source in this paper. A. W. Lawrence’s Trade Castles and Forts of

West Africa, published in 1963, offers readers an architectural examination of many of

the forts now within the bounds of Ghana. His use of historical records and architectural

plans is comprehensive, but the investigation of the relationship between the structures

and the towns, although brief, is an excellent source that many scholars have used as

foundations for their own projects. Christopher DeCorse’s An Archeology of Elmina:

Africans and Europeans on the Gold Coast, 1400- 1900 develops Lawrence’s brief

examination of the role the castle played in the local community through an

archaeological excavations conducted to discover the material culture of the now vacant

land adjacent to the castle. DeCorse’s work completely reoriented the role of Elmina

township and Africans within trade along the coast, proving the importance of

archaeological work in understanding place. A crucial historical and architectural book

published in 1980, Forts and Castles of Ghana by Albert van Dantzig, offers a concise

and well-crafted overview of the developmental history of the forts and castles. These

works provide historical context by examining the history of construction and the social

4

Karl Jacoby. Shadows at Dawn: An Apache Massacre and the Violence of History (London: Penguin,

2009) 233.

4

life of the forts through the nineteenth century, providing with subsequent scholars with a

strong historically researched source of secondary literature.

The Grand Slave Emporium: Cape Coast Castle and British Slave Trade and The

Door of No Return: The History of Cape Coast Castle and the Atlantic Slave Trade by

William St. Clair are extensive investigations into the actual process of transit within the

trans-Atlantic slave trade, shedding light on the role of the second largest structure, Cape

Coast Castle. St. Clair depicts life inside the castle at various levels of power through the

use of unpublished letters and reports. In Stephanie Smallwood’s Saltwater Slavery: A

Middle Passage from African to American Diaspora, the experience of the trans-Atlantic

passage is depicted using Cape Coast Castle as its primary point of departure from

African shores.

Many works published on diaspora memory include the forts and castles, like

Bayo Holsey’s Routes of Remembrance: Refashioning the Slave Trade in Ghana and Ann

Reed’s Pilgrimage Tourism: of African Diasporans to Ghana. Ann Reed’s in-depth

analysis of the relationship between African Diasporans and the interpretation of the

slave forts and castles questions the implementation and realities of the rhetoric

surrounding the pan-African motivation for tourism. Routes of Remembrance thoroughly

examines the collective memory of coastal Ghana’s through interviews, classroom

shadowing, textbook and tour analysis. Holsey’s work concentrates on current costal

perceptions of the forts and castles, while this thesis examines the historical origin of the

public memory of the buildings.

5

Through the use of organizational papers, published surveys, and tour narratives

and notes, the varying emphasis on historical importance can be directly correlated to

institutional purpose and responses to the political climate. While a chronological

approach may offer a perspective on the evolution of the different motivations, an

examination of interpretation will lead to a deeper understanding of the themes that

emerged as the intersections of the power of ownership, historical legacy, and political

placement are understood. Two primary interpretations emerge when analyzing the

motivation for the preservation of the buildings over time: architectural significance and

identity formation, both have national and international implications. It is imperative to

understand how and why the various organizations approached each interpretative theme

differently in order to understand the current interpretation of these historic sites. Other

works concerned with the history and memory of the buildings focus on present-day

interpretation of these sites by investigating tour narratives and preservation methods, but

do not question why these structures have been deemed worthy of preservation.

5

Before

examining the different interpretive themes, a brief introduction to the twentieth

organizations responsible for the buildings allows for a better understanding of how these

themes are interwoven by allowing for organizational commonalities and differences to

be examined.

5

See Bayo Hosley. Routes of Remembrance: Refashioning the Slave Trade in Ghana. Chicago: University

of Chicago, 2007; Brempong Osei-Tutu, “Slave Castles, African American Activism and Ghana’s

Memorial Entrepreneurism” (PhD diss., Syracuse University, 2009); Ana Reed, edit., Pilgrimage Tourism

of Diaspora Africans to Ghana, London: Routledge, 2014.

6

Chapter 2. The Colonial, Post-Colonial, and Global

“As much as we live in a society of organizations, then, it seemed to me that it is

as true, or even more so, that we live in a society of narratives.” Jeffrey K. Olick,

The Politics of Regret: On Collective Memory and Historical Responsibility

There, at the end of the road that ran through Kotokraba market and the heart of Cape

Coast, stands a giant fortress; the sunlight bounces off its the white washed

unsurmountable walls. A taxi driver, awaiting customers eagerly asks, “Where are you

going?” while leaning on his taxi which sits on the paved road in front of massive

building. I point toward the castle to decline his offer. As I walk through the main

entrance past a small art market filled with woodcarvings and oil paintings peddled as

souvenirs for tourists, I take a deep breathe, trying to take it all in. I had returned to this

castle for the third time in my life; at first I was a tourist, then a curious undergraduate,

but now a serious researcher. I knew what to anticipate and I looked for details I hadn’t

noticed before like the giant UNESCO symbol on the entry wall that leads to castles open

courtyard. Who will be in my tour group and what information will be told? A fellow

American intern had traveled with female museum staff the previous week and was

shocked at the insensitive laughter and jokes made during the discussion of rape. I

wondered why I empathized with the female slave stories, when my co-workers did not. I

began to question if it was even possible to empathize with the experience of people

transformed into chattel through the dehumanizing process of enslavement. It was on my

first tour that my interest in the forts and castles was ignited, because I questioned the

7

obvious role identity played in the tour. While questions of identity still remained in the

forefront of my mind, I now questioned why was the castle still here, who sought to

preserve it, and why? I was fascinated by the stories surrounding the ownership of the

building. Outcries about the whitewashing of the walls from the African Diasporan

community, plaques donated by local chiefs apologizing for Ghanaian involvement in the

slave trade, and an international organization’s logo branding the building. This

building was much more than a historic place; its layered history seemed so transparent.

Yet, multiple complex narratives with conflicting voices created for this historic site

overlapped and inundated the memory landscape resulting in chaos. How can this

pandemonium subside without understanding all of the components that led to its

emergence in the first place?

To delve past the traditional history told about these sites, an investigation and

analysis of the various motivations for preserving these historic structures. This is

possible through an examination of the three different organizations that have taken

charge of their memory. The difference in these twentieth century organization’s

interpretations can be examined through an institutional case study that examines the

ordinances responsible for their creation and scholarship produced by and about the

organizations. The Monuments and Relics Commission of the Gold Coast (MRCGC)

which serves as the flagship organization during the colonial period, the Ghana Museum

and Monuments Board (GMMB) whose interpretation initially stems from a reaction to

the immediate colonial past, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO) which pushed the narrative into the global story that is told

8

today, have disparate historical perceptions ranging from an emphasis on the architectural

form to the role of the economy to the international memorialization of slavery.

Each organization had a different mission, yet their interpretations are

intertwined: the MRCGC sought to protect the archaeological heritage of the Gold Coast

for the British, the GMMB was formed to protect the cultural heritage of Ghana for

Ghanaians, and UNESCO was created to protect the cultural and natural heritage of

humanity for all of humanity. The periodization terminology (Colonial, Post-Colonial,

and Global) uncomplicates the overlap found when examining the larger themes by

allowing for multiple organizations, not just the aforementioned key institutions to also

be addressed.

During the Colonial period, there are two documented cases of the forts and

castles being deemed historically important. The Dutch noted near the end of their time in

Ghana that the forts should be repaired for reasons other than maintenance, mainly

architecture, but no work was actually done.

6

The first preservation work done was by the

Public Works Department of the British Colonial Government in the early 20

th

century;

district commissioners were charged with “assessing the site’s condition, indicating

improvements that need to be made, and prioritizing repairs” in conjunction with “three

leading Natives.”

7

While mainly concerned on buildings being used in some

governmental capacity, a letter from Chief Amonu V to the district commissioner written

on behalf of Ft. William’s state asked that “the fort is well repaired, for there are many

historical objects which are known by few persons… the entrance gate was on the

6

Michel R. Doortmont. Castles of Ghana: Historical and Architectural research on three Ghanaian forts

(Axim, Butre, Anomabu)

7

Ann Reed. Pilgrimage Tourism, 863.

9

Western side but where it is at present is the passage through which slaves were sent to

Europe.”

8

So while the first official organization charged with maintain the forts solely

due to their historical importance was the MRCGC, it is important to note that physical

maintenance was conducted on some buildings by the PWA and the transatlantic history

associated with the forts and castles was not forgotten.

Another example of an organization that falls within the period, but is not

necessarily covered in the three institutions discussed later is the Ghanaian Ministry of

Tourism (MOT). Developed in 1993 in order to regulate “one of the fastest-growing

sectors of the economy,” the MOT initiated the Joseph Project which provides a state

based globalization effort juxtaposed to the Slave Route Project conducted by UNESCO.

These projects work with one another, but are developed by separate governmental

agencies and as a result their mission and implementation vary.

9

The different proposed beneficiaries of the memory certainly affect the motives

for preserving the forts and castles. The varying emphases of historical significance

across the organizations sometimes overlap. The extreme emphasis each organization

placed upon architecture, the gold trade, or the slave trade, demonstrates the evolution of

the understanding of the forts and castles; it also highlights the problems that plague their

memory best understood as a metaphysical tug-of-war for control of the space. So while

fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth Europeans struggled to

control the buildings for trade purposes, these twentieth century organizations fought for

control of the forts and castles interpretation.

8

Ann Reed. Pilgrimage Tourism. 886; this passage would later be interpreted as the “Door of No Return”

which is discussed in the section on African Diasporan Identity.

9

Later discussed in the Identity Formation section..

10

Chapter 3. The Forts and Castles of Ghana

Although other trading fortifications were built along the west coast of Africa,

historically referred to as the Guinea Coast, the concentration of buildings was densest

along the Ghanaian coastline with an average of one fortification every ten miles.

10

Ghana’s geological composition is responsible for the proliferation of these European

structures for two different reasons; Ghana is uniquely endowed with gold, and the

Ghanaian coast is rich with an abundance of capes and promontories.

11

While access to

trading opportunities remained the most crucial element when selecting a location for a

trading post, the strategic placement on an elevated area or coastline that protruded into

10

Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Museum and Monuments Board, 1999)

20.

11

The Grain Coast roughly stretched from Sierra Leone to western Ghana and was named for the export of

melegueta pepper referred to as the grain of paradise. The Slave Coast is commonly used in conjunction

with the coast of the Bight of Benin, which is part of the Gulf of Guinea, begins in eastern Ghana and ends

in southwestern Nigeria; however due to the proliferation of plantations in the New World the boundaries

of the Slave Coast seemed to expand to include all of the Gold Coast. Gold would continue to be an export

but by the early eighteenth century the export to England accounted for £ 200,000.

11

Figure 3.1 Map of the extant forts and castles of Ghana

Scattered across the coastline of Ghana is the densest concentration of European fortification in sub-

Sahara Africa. All built to consolidate power in trade, this map shows the location of the remaining forts

and castles. See Appendix A for a detailed reference map of the extant forts and castles of Ghana.

11

the gulf was also given great consideration due to its ideal defensive position.

12

During

the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the forts and castles built along the coast were

used to facilitate the trade of black bodies. The amount of slaves from the gold coast, the

fifth largest slave-exporting area, was still extremely high illustrating the amount of trade

occurring along the coast. Of the estimated 12.2 million slaves shipped across the

Atlantic to the Americas, 1.2 million embarked from the Gold Coast.

13

The rise in

competition between the different European powers, which increased over time as the

New World plantation system developed, resulted in a rapid buildup of fortifications

along the coast. While the slave trade is mentioned in all three institutional case studies, it

becomes the secondary story to architecture and trade relationships until the memory of

these sites is stretched to a global level.

Along 255 km of Ghana’s topical shoreline, twenty-three European buildings

stand out compared to the vernacular buildings that surround them. They are the remnants

of a once lucrative trade which shaped the entire region of West Africa. Varying in size

and style, the forts and castles of Ghana now provide local communities with a revenue

stream and constitute the nation’s thirds largest industry after cocoa and gold, through the

tourism industry created by both the Ghanaian government and international bodies.

14

This source of tourism is built upon the memorialization and representation of the trans-

Atlantic slave trade.

12

Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Museum and Monuments Board, 1999)

20.

13

Emory University’s Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (Atlanta: np, 2009).

http://www.slavevoyages.org/tast/database/search.faces

14

Ferdinand de Jong, edit. Recalling Heritage: Alternative Imaginaries od Memory in West Africa. (Walnut

Creek, CA: 2007) 73..

12

The forts and castles were the major point of departure from the Ghanaian

coastline and were used to stock pile goods for ships, allowing for ships to fill their decks

with cargo in days instead of weeks. Although the first forts and castles were built to

facilitate the gold trade, most were eventually converted their warehouses for the

emergence of a new commodity, black bodies. Over one million Africans would be

shipped from the Gold Coast across 300 years, resulting in a disruption of African

population growth, a hemispherical dissemination of African cultures, and the

development of an increasingly prominent capitalistic economy.

These twenty-three buildings are in four various stages of preservation: tourism-

driven rehabilitation, general preservation, neglected preservation, and repurposed

rehabilitation. The journey to each fort and castle proved to be instrumental in

understanding the variation within the preservation of the forts and castles as well as

providing a small snapshot of local knowledge surrounding the sites. Elmina and Cape

Coast Castles are the most accessible because of the well-developed infrastructural

support provided to assure the continued growth of the tourism industry. Truly the only

issue that seemed to plague the journey, in the minds of those charged with presenting the

castles was creating a peddler-free space.

13

The first time I travelled from Cape Coast to Elmina, I had an entirely unplanned day so I

chose to walk. As I passed a group of young coconut sellers masterfully scaling trees,

knocking their livelihoods from the palms, the outline of Elmina Castle began to emerge

from the coastline. The fortress sparkled thanks to mid-day sun beaming down upon its

whitewashed walls. I finally reached the beginnings of Elmina, a corruption of the

Portuguese name for the area El Mina translated as the Mine. Although it is just a town,

traffic congestion of the painted boats in the lagoon that cuts through the promontory

proves that Elmina is a hub of the local fishing industry. Forced to walk along the street,

I walk past old men teaching youth to mend on nets for tomorrow’s venture. I buy a quick

snack of groundnuts and a water sachet from a girl just outside the wall that surrounds

the castle. On the wall a sign states that only those continuing to the castle are allowed;

getting to Elmina Castle is only difficult if you are a peddler trying to sell painted sea

shells and beaded bracelets. The whitewash creates a perfect contrast between a

Figure 3.2 St. George’s (Elmina) Castle from Fort Saint Jago

A View of St. George’s Castle and Elmina’s lagoon from the strategically placed defensive fort on top of

Saint Jago Hill, the namesake of the fort (van Dantzig 16). The proximity of the castle to the town of Elmina

is apparent as its spatial separation created through buffer zones.

14

cloudless, blue sky and a glimmering St. George’s Castle; surrounded by the booming

fishing industry of Elmina which crowds the lagoon with brightly painted longboats, St.

George’s Castle, more commonly known as Elmina Castle, triumphantly stands out

amongst the sprawling local architecture and a few remaining colonial buildings. The

status of the forts and castles vary from building to building as do size and style. One of

the crowning jewels of the Ghanaian tourism industry, St. George’s Castle is the largest

and oldest fortification. Built by the Portuguese in 1482, the original purpose of this fort

is still debated; while it is agreed that it was established to gain a foothold in the West

African gold trade, it has been suggested by van Dantzig that it could have also been built

as a base for potential military campaigns when size of Africa was still unknown.

15

Walls

surround a couple of empty acres just outside the castle where archaeological excavations

unearthed the untold history of the relationship between the castle and the town, as well

as the everyday life of Elmina during the height of the trade.

16

Subsequently, these walls

that were built to protect the archaeological remains of Elmina’s integral contribution to

the castle now separate the town from the historic building; in addition it has created a

buffer between tourists and the local Elmina population. A 1998 State of Conservation

report conducted by UNESCO sites the lack of buffer zone, which prevents “the

encroachment of human settlements and activities on the areas in the direct vicinity of the

World Heritage sites,” as one of three main threats to the forts and castles of Ghana.

17

While the erection of this wall may have been spurred by the desire to create a buffer

15

Van Dantzig. Forts and Castles of Ghana. 5.

16

Christopher DeCorse, An Archaeology of Elmina: Africans and Europeans on the Gold Coast, 1400-

1900, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2001.

17

UNESCO, World Heritage Committee State of Conservation Documentation, Forts and Castles, Volta

Greater Accra, Central and Western Regions, by UNESCO, 22COMVII.35, (N.p.: UNESCO WHC, 1998),

http://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/2238.

15

zone in order to safeguard the buildings, many believe that this created to make tourists

more comfortable.

18

Although the terminology may create a grander image than the actual building,

the castle is over 9,000 square meters, making it the largest in Ghana.

19

Its purpose has

changed over time, but has consistently been used in an administrative capacity. It began

as the only trading post along the newly discovered Gold Coast, but later became a

storehouse that maintained the slave populations held within its storage spaces.

20

Following the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the castle would become a European

center of power, house a post office, a prison, the Ghanaian police training academy, and

ultimately a museum which focuses on the history of Elmina.

18

Brempong Osei-Tutu, “Slave Castles, African American Activism and Ghana’s Memorial

Entrepreneurism” (PhD diss., Syracuse University, 2009), 66.

19

Judith Graham, “The Slave Fortresses of Ghana,” New York Times, November 25, 1990, accessed March

20, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/1990/11/25/travel/the-slave-fortresses-of-ghana.html.

20

Elmina has the distinction of having an early limited role in the Gold Coast slave trade due to the

Portuguese wanting to maintain the amiable gold trade relationship established and the ability to purchase

slaves from Benin. (Routes of remembrance location 391, taken from Rodney 1969,14).

Figure 3.3 Interior view of Cape Coast Castle

Although the whitewash is due for a new coat, the complete nature of Cape

Coast’s buildings is incredible considering its age and proximity to the sea.

16

Tourists don’t travel to Elmina for the museum located within the former Dutch

church that tells the history of Elmina the town, but for the tour that is offered of the

castle which allows visitors to explore practically every corner of the building with a tour

guide. Dark, airless cells where rebellious slaves were punished are compared to the tall,

damp rooms where male slaves were housed. An open courtyard where female slaves

were held and could be selected from an above balcony for the physical comforts of high

ranking European officers is juxtaposed against the nearby Dutch church in the courtyard

of the castle. But this well-preserved building is not typical when discussing the forts and

castles; its unique position as a hub of tourism has led to its now costly, conserved state

funded by the Central Region Integrated Development Programme.

21

Elmina Castle’s level of preservation and representation is indicative of the

tourism-driven rehabilitation preservation that surrounds the site and can be seen by

tourists at three other sites: thirteen kilometers east at Cape Coast Castle the other jewel

of Ghanaian tourism, 100 kilometers west at Fort St. Jago where tourism is an emerging

market, and 140 kilometers west at Fort Apollonia where an Italian collaboration has

converted the fort into a museum about local history and culture. Tourism has driven the

large-scale, high-cost preservation methods used at this small selection of the forts and

castles like buying the proper, and more expensive, paint to preserve the cannons and

cannon balls.

22

21

This program will be further discussed in the section on African Diasporan Identity. And while it was

funded by the CRIDP, the real funding sources are the UNDP and USAID.

22

Bordoh, Ebenezer Collins. Personal interview. 15 November. 2011.

17

Two years later, I returned to Ghana to help document the forts and castles and travelled

to each site. Getting to Fort Amsterdam proved more challenging than Elmina Castle, but

it was not impossible. I alighted from a bus heading from Accra to Cape Coast at

Abandze, crossed the busy highway, and began to walk towards the large structure

visible from the street. I was stopped as I started to climb the hill by a group of older men

playing Damii; they asked where I was going and what I was doing. When I told them I

wanted to tour the fort, one yelled across the street to a small boy working at a store and

told him to go and fetch my guide. While I waited for my tour guide an afternoon rain

began, I took refuge underneath a nearby canopy and the men continued to play while

boisterously laughing and loudly shouting at one another. As I look up the hill, I can’t

help but compare the imagery of Elmina, a clean, local-free, white washed building, with

that of Fort Amsterdam, an open, dark façade against a grey stormy sky.

Thirty kilometers from Elmina on the highway that stretches across Ghana’s

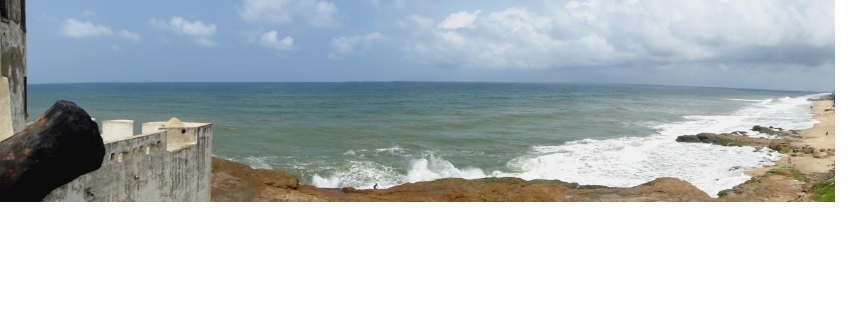

coast, Fort Amsterdam sits overlooking the ocean from atop a large hill. Fort Amsterdam

Figure 3.4 Interior view of Fort Amsterdam

Portions of walls were demolished during the Dutch-Anglo war, but

were rebuilt for tours.

18

was the infamous source of rebellious Cormantin slaves; Cormantin slaves received that

name from the original plan to construct the fortification in Cormantin. However, local

people stole bricks at night, delaying process, so the fort was moved to Abandze. The

lack of whitewash exposes the local and European stones, oyster shells, and palm oil that

comprise the buildings walls which now form around an overgrown courtyard. While not

quite a ruin thanks to the substantial amount of extant walls and partially collapsing

staircases, this fort’s preservation and conservation sharply contrasts with that of the

glimmering, complete walls of Elmina Castle. Deviating from the typical tour discussed

later, the tour of Fort Amsterdam heavily emphasized the history specific to the fort; a

thorough discussion of the forts contested construction, the detailed accounts of battles

between European nations and their Africans allies, and a tour of the architectural

layering are examples of the narrative that speaks directly to Fort Amsterdam, not to the

forts and castles as a whole. While the history of the fort’s location differentiates it from

the other forts and castles resulting in another narrative experience for curious travelers,

the tour still focuses on the fort’s use during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. This fort’s

status emblemizes the general preservation state of most fortifications along the coast; it

has been actively protected and efforts are made to continue its conservation and

interpretation by local representatives of the governmental body which owns the

property. While ideally the positions are given to local community members, the hiring

process for guardianship is unclear. At Fort Amsterdam, my tour was conducted by a

recently graduated high school student as his father, who was the custodian, shadowed us.

At Fort Saint Jago the son of Fort Friedrichsburg’s custodian led my tour. Both forts

19

Figure 3.5 Remains of Fort Nassau

A white sign warns visitors and residents that Fort

Nassau is state property, but various buildings have

been constructed immediately surrounding it.

Figure 3.6 Africa Through a Lens Quarters For

Nassau, Moru

A photograph from the 1890s shows a significant

amount of the fort intact..

From the National Archives UK – CO 1069/34

lacked signs indicating the price of a tour illustrating the inconsistent policies of

preservation, and presentation, of the forts and castles.

My trip to Abandze followed my journey to find Fort Nassau. Located next to the Cape

Coast metropolitan of Morre, Fort Nassau was one of the forts in ruins. Unsure of where

the fort was, I headed towards the largest hill I could find; my travels had turned me into

a landscape whisperer, I began to look for the geographic cues indicating where a fort

might be found. I started weaving through dirt paths while goats and children chased

after one another in between small concrete and wood homes. I spotted a large piece of a

yellow brick foundation at the top of a nearby ledge. After struggling to climb up red

clay, I had finally found the remains of Fort Nassau; more than the foundation, pieces of

the fort protruded up from the ground sporadically. I then walked around the visible

pieces which had remnants of whitewash clinging to the brick and found a white sign

warning to keep off Fort Nassau, it’s state property.

20

Between Elmina Castle and Fort Amsterdam, lies an extreme case of

conservation neglect; on top of eroding clay hill remnants of Fort Nassau sporadically jut

into the sky. Considered to be ruins, the remains of the building have a sign noting what

they are and warn against tearing the building down. Fort Nassau’s condition was

worsened over time as the town of Moree began to develop in the nineteenth century

when the fort because a source of building materials due its vacant appearance and lack

of use. Following the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, these forts were either left as

vacant structures or, in rarer instance, repurposed by locals. These smaller, less centrally

located forts were frequently left as vacant structures due to fear of the spiritual qualities

that some local communities associated with the building’s history. Tours are not given

and information beyond the name of the fort is unattainable at the site; intrigued children

peer out at me from underneath a nearby unfinished building, suggesting that the site is

rarely visited by outsiders.

These physical state of these forts, the ones that lack tourists, illustrate the

problematic way that funds are distributed across all the forts and castles; forts without a

tourism base, which include the majority of the forts, lack funding resulting in the

neglected preservation stage, while tourist hubs like Elmina Castle and Cape Coast

constitute the majority of the GMMB’s current spending.

Accra, the capital of Ghana, with almost 3.8 million people has the largest

population in the country and its sprawling expansion ranks it as the eleventh largest

metropolitan in Africa and the 93

rd

largest in the world.

23

It is the seat of Ghanaian

23

“World City Populations,” World Atlas, accessed May 1, 2015,

http://www.worldatlas.com/citypops.htmInsert census information.

21

government and home to two historic buildings: Osu Castle, formerly known as Fort

Christiansborg, and James Fort. Both are rehabilitated and repurposed in unique ways.

Most of the forts and castles have been repurposed, predominately as heritage tourism

sites, but Osu Castle and James Fort are used for entirely different purposes. James Fort

is one of Ghana’s forty- five prisons and because it is a prison, it is not open to the public.

It has been physically preserved for its utilitarian use as a prison which began during the

colonial period. Fort William in Anomabu was used as a prison during the colonial period

as well, but has been repurposed for tourism since 1993. As a result of its colonial

function, additional buildings were added to provide service to the inmates.

24

Fort

William’s current stage of preservation should qualify as general preservation as a result

of its unpopularity with tourists, but its actual state of physical preservation would

suggest that it has received more attention. It should be expected that James Fort would

parallel Fort William following its unforeseeable closure as a prison. Osu Castle was the

seat of colonial power was located at Cape Coast Castle, but moved to Accra in 1887. Its

24

Fort William Tour. Fort William. Anomabu, Ghana. 10 July 2014.

Figure 3.7 Interior view of Fort William

The building with a flat roof was remodeled as the prison’s

kitchen. The tour states that the building was historically used

as a slave mart.

22

function as the seat of government was continued when Ghana gained its independence

and it was converted into the president’s residence; as a result, this fort has had the most

restoration and its architectural style was greatly compromised during a modern

reconstruction of its upper levels.

25

This building is also closed to the public, due to its

function, but it has been used as the site to discuss the current state of the forts and castles

with international governments. These three buildings have been physically preserved in

distinct ways due to their different repurpose roles, but are better preserved than most of

the forts and castles.

Following the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the forts and castles of Ghana

entered into historical limbo. With the various dates of abolishment of the slave trade,

beginning with the British in 1807, the amount of slaves leaving the Gold Coast rapidly

decreased from 178,480 slaves from 1776 to 1800 to 4,624 slaves from 18186 to 1830.

26

Caught in between their purpose as trade centers and their later iterations as memorials to

that same trade, some became vacant buildings used for construction materials, others

were cast aside and forgotten, and many were used by the remaining European powers

still interested in laying claim to the Gold Coast. Their various physical states attest to

varied nature of their histories, but what accounts for their current purpose? Their

historical limbo ended upon the emergence of governmental powers that sought to

preserve their memory. Now these sites are visited by various groups from African

American tourists interested in pilgrimages to German non-profit volunteers to Ghanaian

school groups, but the narrative is primarily concerned with thoughts of an audience

25

Implications of this repurpose are further discussed in the section on Ghanaian identity formation.

26

T.M. Reese. “’Eating’ Luxury: Fante Middlemen, British Goods, and Changing Dependencies on the

Gold Coast, 1750-1821 ” William and Mary Quarterly, 2009) 66(4): 851-872; Hosley. Routes of

Remembrance. (LondonL Routledge, 2014) 427.

23

intent on learning about their trans-Atlantic slave trade pasts, made possible through the

evolution of their historical narratives.

27

While evolution suggests a linear progression,

the historical memory constructed for and around the forts and castles of Ghana is truly a

story of adaptation. The memory changes as the organizations react to the political

atmosphere and national and international pressures.

27

See Reed’s Pilgrimage or Brempong’s dissertation for further discussion of the concept of pilgrimage

24

Chapter 4. Model Architecture

“Architecture is to make us know and remember who we are.”

– Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe

My itinerary was set; I knew the coastal towns and cities where the remnants of the forts

and castles were located. I was dependent upon the hospitality and generosity of my

fellow travelers and the tro-tro drivers and mates to actually reach my destinations. On

the way to the Brandenburg-Prussian fort, Groß Friedrichsburg, the dirt road had

transformed into a muddy pit, where a large truck carrying the town’s water supplies was

trapped. The driver told everyone to get out, turned the van around, and headed back

towards the main road. I asked a fellow passenger how far Princesstown was: four

kilometers and the only option was to walk unprotected from the high afternoon sun.

After navigating past the mud, the road emerged once more and I began to calculate my

arrival time. A small boy passed boy on a bike much too large for his small legs. I wished

him a good afternoon in Twi, and he slowed in curiosity; an obroni speaking Twi while in

a Fante area would have piqued anyone's curiosity. We ran through the phrases I knew

and he asked if I knew how to drive a bike. It had been a while since I last rode a bike,

but I seized the opportunity to get to Princesstown faster. Jonathan masterfully hopped

onto the back of the bike as I began to pedal and our conversation continued as we made

our way on the relatively flat road. I asked him about his knowledge of the fort and he

explained that he had gone once with his school. Houses began to line the road as we

approached the town and Ghanaians on their porches stared at the odd travel

25

companions we made; some called out to Jonathan, others I greeted in Twi which usually

resulted in laughter. Princesstown was visited by obronis from time to time as a result of

the fort’s conversion into a guesthouse, but few make the “arduous” journey from the

typical centers of tourism.

Once I climbed the hill along a beaten path and entered into the freshly macheted

courtyard, the architectural distinction of Fort Friedrichsburg immediately struck me.

While the journey to this fort was certainly unique, its architectural features truly

distinguished it from the other buildings I had encountered. This was the sixteenth fort I

had traveled to in the past three weeks and it was unlike any of the others. The stone

finish contrasted with the usually whitewashed walls I had grown accustomed to seeing;

the layout of the fort which used several multi-storied buildings instead of the usual one

large multi-storied building, and the location on a steep hill were also incredibly

different. Upon seeing its unique features like the small shuttered windows and the

separated round tower, I finally realized how important architecture is to studying the

forts and castles. In addition to visually understanding their layered history,

architectural studies allow for the historic specificity of the forts to truly be examined.

Figure 4.1 Interior view of Fort Friedrichsburg

The only remaining Brandenburg-Prussian fort, Friedrichsburg’s small arched windows and symmetrical

design architecturally distinguish it from the other forts and castles.

26

The forts and castles vary in type, size, and style; these variations would be the

initial catalyst for preserving the buildings. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to

arrive on the Gold Coast in the mid-fifteenth century; their first permanent trading post

became the trade model for all subsequent European countries including the Netherlands,

England, Denmark, Portugal, Sweden, France, and Brandenburg-Prussia.

28

The arrival of

these other European nations spurred the innovation of new architectural styles based

upon medieval fortifications, but also having to adapt to the unfamiliar environment of

the Gold Coast.

29

The 1979 World Heritage List extends protection to “three castles,

fifteen forts in a relatively good condition, ten forts in ruins, and seven sites with traces of

former fortifications.”

30

A brief discussion of basic architectural distinctions is necessary

when discussing the importance of architecture in the narrative surrounding the buildings.

There were three different structures used as trading fortifications in Ghana: the lodge,

the fort, and the castle. Lodges were small, temporary structures usually constructed from

“earthen materials,” and were used while a fort was being constructed. As a result of their

temporary function and construction materials there are no surviving lodges, but many

were located near the sites of later fortifications.

31

Most extant structures are forts that

were made of brick or stone and had multiple rooms for storage, offices, and garrisons.

The largest and most rarely built were castles which consisted of the same elements of a

fort but on a grander scale and featured a “network of buildings” that were capable of

28 Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Museum and Monuments Board,

1999) 20.

29

Van Dantzig, 13.

30

UNESCO, World Heritage Status Of Conservation Report, Forts and Castles, Volta Greater Accra,

Central and Western Regions, by WHC, 1998 (n.p.: UNESCO WHC, 1998).

31Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Museum and Monuments Board, 1999)

10.

27

sustaining a much larger population.

32

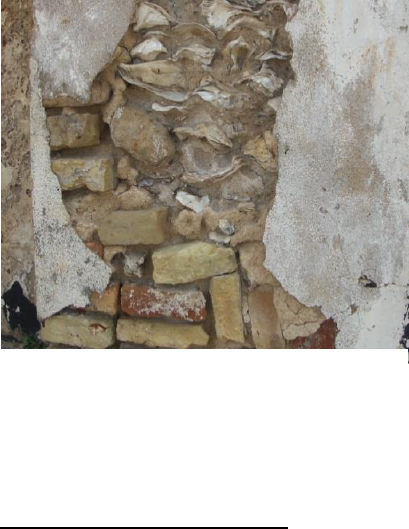

Both forts and castles were made from brick or

stone that were usually imported due to local stone being too weak and bricks being too

difficult to manufacture locally; some methods of construction included native materials

and methods such as the use of oyster shells in outer walls and palm oil for

waterproofing.

33

Castles, in addition to their roles as a fort, were used as headquarters and

were commonly paired with a defensive fort. Although it could be argued that they did

help facilitate trade and were therefor built for that purpose, defensive forts were the only

exceptions when discussing the universal purpose of the fortification as trade. Because of

the central focus trade relations play in the overall interpretation of the site, it is important

to distinguish that the vast majority of the buildings were either constructed or

repurposed to facilitate in the trade of black bodies. The construction of defensive forts

emerged after other European countries began to compete for control of Gold Coast trade.

32

Kwesi J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana (Accra: Ghana Museum and Monuments Board, 1999),

11.

33

A. W. Lawerence, Trade Castles and Forts of West Africa, (London, 1963); Notes from tour James-

Ocloo Akorli, tour for Fort Prizenstein, Keta, Ghana. 9 July 2014.

Figure 4.2 Fort Keta’s Wall

An exposed wall, washed away by the sea, shows

the use of foreign brick and local oyster shells in

the building’s walls.

28

An explanation of the variation within architectural styles and types is available

within an exhibition at Cape Coast Castle; other tours of the buildings may explain the

difference between a fort and castle, while some delve into more detail about the types of

building material, but as a whole the narrative surrounding the architecture of the

buildings is neglected. A rise in competition for control of the trade resulted in the

proliferation of fortification construction along the coast of Ghana; the architectural

layout depends on what time period the building is created for trade and what European

entity is responsible for its construction. Meaning that the impact of what is being traded

and who constructs the fortification directly impacts its architectural style. It is this

diversity of architecture, most specifically the diversity of European fortification

architectural style that sometimes appears in layers as the buildings exchanged hands,

was the preservation catalyst for the administration of the Colony of the Gold Coast.

The first organization that charged itself with the preservation of the forts and

castles for non-utilitarian purposes was the Monuments and Relics Commission of the

Gold Coast (MRCGC). Monument and relics commissions were commonly established

by the British Empire for its colonies as seen in Sierra Leone and South Africa, but the

forts and castles are a unique case due to their size. While these government

organizations created the infrastructure for current models of preservation, most were

exploitative of archaeological artifacts. An unsurprising program of imperial and colonial

aggression was the raiding of a colonized country’s most valuable archaeological

artifacts. This practice was not limited to the marbles of the Parthenon, but occurred

throughout all British holdings including Ghana. While terracotta figures from Northern

Ghana, commonly referred to as Komaland, were susceptible to colonial plundering, the

29

forts and castles were saved because they were impossible to move. However, the

inability to extract did not mean that the MRCGC was not interested in the buildings.

34

The commission was created by an ordinance of the same name in 1945 at the request of

the research department of the colonial office. The MRCGC was formed for “the

preservation of antiquities and the restoration of architectural monuments.”

35

Transactions of the Gold Coast and Togoland Historical Society was a journal created in

1952 as a conduit for the research findings of commission members.

36

The commission

was comprised of British archaeologists and ethnologists who taught for various

universities in Ghana. These commission members were also the first to produce

historical and archaeological accounts of Ghana.

MRCGC sought to preserve the forts and castles in order to save medieval

European fortification architecture; certainly they also were conducting historical

research about the forts, but it was mostly concerned with how land was acquired and

unsurprisingly focuses on the European experience. The two sources for understanding

the MRCGC’s motivation and interpretation of the forts and castles are located in the

work its members produced, books and academic journals that introduced scholars to the

history of Ghana, and in B.H. St. J. O’Neil’s 1951 “Report on Forts and Castles of

Ghana.” Between 1952 and 1959, three different articles were published by the historical

society charged with discussing and protecting the history of the Gold Coast. All three

34

The emphasis on studying architecture can also be seen in British accounts and research of medieval

castles, like Kenilworth Castle, being produced in this period. However, these studies also go into great

detail on the history of the places illustrating that the lack of history included in the Gold Coast studies is

not indicative of the period.

35

Benjamin W. Kankpeyeng and Christopher R. DeCorse, “Ghana’s Vanishing Past: Development,

Antiquities, and the Destruction of the Archaeological Record,” African Archaeological Review 1:2,

(2004): 94.

36

The journal was renamed following Ghana’s independence to The Transactions of the Historical Society

of Ghana.

30

concentrate on the architectural components of the forts and slight the forts’ non-military

functions. The first published essay by W. J. Varley, a member of the MRCGC, states

that “the nature of the trade, the rivalries it engendered, and their effects upon the history

of the Gold Coast” is not in the scope of the essay because of the amount of literature

already established on the topic.

37

However, Varley avoids discussing the economic

origins for the rise in European rivalries when explaining the evolution of the

architectural features of the forts.

38

Fort William in Anomabu is the focus of the second

essay, but this time archaeological examination of architecture is used to understand the

fort’s name. A thorough discussion of the European entities that fought for control of

Anomabu, as well as a brief history of European monarchs, produces an answer to the

question of why is it named Fort William; European interactions make up the bulk of the

argument, but an analysis of the architectural layering is used as a primary source.

39

The best example of the MRCGC’s understanding of the forts and castles is A. W.

Lawrence’s 400-page monograph, complete with historical drawings and architectural

plans, of the architectural development of the forts and castles of West Africa.

Commonly cited by those who now study these structures, Lawrence’s in-depth analysis

of the influence of medieval military fort architecture is truly the epitome of MRCGC’s

historical understanding of the structures as examples of European fortification

architecture. While most of these publications mention the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the

emphasis on the architectural value of the sites overwhelms the interpretation

37

See van Dantzing, Lawerence, Reed, Hosley

38

W. J. Varley, “The Castles and Forts of the Gold Coast,” Transactions of the Gold Coast & Togoland

Historical Society 1 (1952): 1.

39

M. A. Priestley, “A Note on Fort William, Anomabu,” Transactions of the Gold Coast & Togoland

Historical Society 2 (1956): 46-48.

31

demonstrating that the MRCGC wanted to save the forts and castles for their European

architecture.

Certainly an investigation of the architecture of the structures provides another

historical resource; by using the buildings as material culture, the narrative created

examines “the relationship between different cultural areas at a given moment.”

40

However, assuming the notion of “structure as constant and history as process” in which

an architectural study requires an admission of the historians influence on interpretation

because the “history provides architects with a set of existing building forms and a set of

factors that have enabled or restricted possibilities.”

41

The architecture of the forts and

castles serve as a piece of material culture; it is up to the archaeologist, the historian, and

interpreters to engage with the “constant structures” that offer literal layers of history. So

while they may not be documents in an archive to be read, they are historical evidence to

by analyzed.

40

Sophia Psarra, Architecture and Narrative: The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning, London:

Routledge, 2009.

41

Sophia Psarra, Architecture and Narrative: The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning, London:

Routledge, 2009.

Figure 4.3 Detailed Interior of Fort

Amsterdam

The shape of the windows vary as a

result of both British (rounded windows)

and Dutch (rectangular windows)

architecture being used.

32

This architectural understanding is further elaborated upon in “Report to the

Chairman and Members of the Monuments and Relics Commission of the Gold Coast

upon the historical growth, archaeological importance, the general condition and the

present use of the castles and forts of the Gold Coast with a view to their better

preservation as ancient and historic monuments” written by Great Britain’s 1951 Chief

Inspector of Ancient Monuments, B.H.S. J. O’Neil. As a result of time constraints and

accessibility, O’Neil’s report covers nineteen of the then twenty-nine extant buildings.

Appalled at the state of disrepair, O’Neil’s report is concerned with the appearance of the

structures stating that “On a tropical shore with the blue of the sea, the yellow sand and

the green coconut palms, the staring whiteness of the building is needed to complete the

picture. It used to do so, it should do so again… the absence of whitewash which makes

Cape Coast Castle so depressing to the visitor.”

42

The whitewashing of the structures has

been heatedly discussed due to the perception of the whitewash as whitewashing the

slave trade history; while the whitewash is the appropriate preservation tactic used to

protect the buildings from humidity, O’ Neil’s comment on the whitewash as a source of

beauty, not as a necessary prevention, would certainly bolster modern arguments on the

subject.

43

His report details the European arrivals to the Guinea coast. It mentions that

further elaboration on the slave trade seemed unnecessary due to its discussion in

previous scholarly works, “although it was the raison d’etre of most of the forts.”

44

The

rest of his report focuses on the physical condition of the forts and castles, while also

42

Bryan Hugh St. John O’Neil, “Report on Forts and Castles of Ghana,” Accra: Ghana Museum and

Monuments Board, 1951, 3.

43

“Is the Black Man’s History Being ‘White Washed’: The Castles/Dungeons of the African Holocaust”

(1994, 48) from Routes and remembrance location 2275

44

Bryan Hugh St. John O’Neil, “Report on Forts and Castles of Ghana,” Accra: Ghana Museum and

Monuments Board, 1951, 14.

33

offering initial architectural evaluation; because the buildings exchanged hands across

centuries and because they were repurposed for trading in human beings instead of gold,

a layering of architecture occurs. For instance, when examining Elmina Castle traces of

Portuguese, Dutch, and English architectural fortification styles can be seen, offering

visual evidence of the contingent ownership of the slave castle. The forts and castles of

the Gold Coast were isolated examples of European medieval forts that could not be

found elsewhere due to the development, repurposing, and destruction of European forts

on the European continent. It was their uniquely European architecture that served as the

first motivation for their consideration as both an important historical and monumental

site.

Days before Ghana’s independence, March 6, 1957, Ordinance 20 merged the

MRCGC with the interim Council of the National Museum, creating the Ghana Museums

and Monuments Board (GMMB).

45

The forts and castles were the first sites to be

proclaimed national monuments due to the age of the structures as well as the emphasis

previously placed upon them by the MRCGC.

46

In 1969, the GMMB was further defined

by the National Museum Act which explained the duties of the board; while focused on

the maintenance of museum, this act also required the board to “preserve, repair or

restore any antiquity which it considered to be of national importance,” making the

GMMB the official organization responsible for the preservation of the forts and

castles.

47

Being listed as National Monuments afforded a level of protection to the forts

45

“Ghana Museums and Monuments Board,” Cultural Heritage Connections, accessed September 30, 2014,

http://www.culturalheritageconnections.org/wiki/Ghana_Museums_and_Monuments_Boards.

46

National Liberation Council Decree 387 of 1969, Establishing the Duties of the Board, National Museum

Act, section 14 (1969).

47

Henry Cleere, Archaeological Heritage Management in the Modern World, London: Routledge, 2005,

125; Other GMMB properties include, but are not limited to the Asante Traditional Buildings, which are

34

and castles; local authorities, usually elders and chiefs, were notified and signs were

posted to remind would-be vandals that the properties belonged to the government.

48

The

GMMB continued to justify the preservation of the forts and castles as a result of their

architectural significance which is seen in their nomination of the sites in 1979 to the

World Heritage Committee (WHC) hoping to see the inclusion of Ghana on the World

Heritage list.

World Heritage properties are divided into two different categories, cultural and

natural, although a site can claim both. Cultural heritage sites, like the forts and castles,

are defined by UNESCO as “monuments… architectural works, elements or structures of

an archaeological nature,” that are either “works of man or the combination of nature and

man… [with] outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or

anthropological point of view.”

49

Properties are selected by the World Heritage

Committee from a list of state-submitted inventories of heritage, guaranteeing that sites

inducted have the consent of the state in which the property is found. Funding for the

preservation and management of World Heritage sites is funded from less than one

percent of contributions to UNESCO, private and public foundations, the state in which

the property is located, and international assistance.

50

The first list was completed in 1978

and consisted of eight cultural properties; the current list has 779 cultural properties.

Although it has an ambitious mission, UNESCO’s World Heritage List is an international

also inscribed on the World Heritage List; archaeological sites in northern Ghana; the Ancient Mosques of

the three Northern Regions; Wa Naa’s Palace; Gwollu and Nareligu Defence Walls used to prevent

enslavement; and the Old Nacrongo Catholic Cathedral.

48

Ebenezer Bordoh, e-mail message to author, November 17, 2014.

49

UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (Paris:

n.p., 1972), Article 1.

50

UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (Paris:

n.p., 1972), Article 16; Ibid., Article 21.

35

collection of properties that strives to encapsulate the natural and cultural experiences of

mankind across the globe. The interesting element on the GMMB’s nomination form is

the reasoning for the choice of cultural; the forts and castles are listed under section (IV)

which claims the property is, “an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural

or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human

history.”

51

The justification for section iv must be attributed to the architecturally historic

understanding of the forts and castles, as first argued by the GCRMC, but can also be

attributed to the GMMB’s shift from architecture to the equitable relationship between

Africans and Europeans that occurred prior to colonialization.

The impressive size and physical presence of the forts and castles demands an

appreciation for their architecture. The initial catalyst would be the history of design and

evolution of style seen in the layering of architecture. This architectural emphasis ensured

that the buildings were physically preserved later allowing for their interpretation to

penetrate past their stone facades to the core of their power of memory.

51

“The Criteria for Selection,” World Heritage Convention, accessed March 5, 2014,

http://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria.

36

Chapter 5. Pan-African Heritage and Identity Formations

An examination of “who want whom to remember what and why” through an

analysis of the development of the field of memory studies, the impact of globalization,

and the advent and surge of heritage tourism, is a fundamental to understanding the ways

in which the commemoration of the transatlantic slave trade takes place within Africa.

52

Although group memory can be traced back to the Archaic Greek, collective memory

used in a contemporary sense is typically traced to Emile Durkheim.

53

Considered to be

the father of sociology, Durkheim’s discussion of commemorative rituals led to his

student, Maurice Halbwach, coinage of the term collective memory in the early twentieth

century.

54

By discounting the biological conception of memory and ascribing an

understanding of memory within the context of society, Halbwach was able to theorize

that memory is acquired through socialization and is subsequently produced and

performed in society.

55

Halbwach made a crucial distinction between history and

collective memory stating that “history is the remembered past to which… is no longer

and important part of our lives – while collective memory is the active past that forms our

52

Alon Confino, “Memory and Cultural History: Problems of Method.” The American Historical Review

102:2386-403.

53

Nicolas Russell. “Collective Memory before and after Halbwachs.” The French Review 79: 792-804.

54

Maurice Halbwachs. The Social Frameworks of Memory. 1925.

55

Jan Assmann, “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique. 65: 1995. 125-133.

37

identities.”

56

This interpretation of collective memory is pivotal to the approach of

commemorating the transatlantic slave trade because those memory rituals require self-

identification, whether as an African, African Diasporan returning home, or an

international tourist on holiday.

Creating Ghanaian

“Until the Lion has his historian, the hunter will always be a hero.”

– African proverb

As I begin to dig into the rough, yet moist ball of kenke in front of me, my co-workers

from the National Museum continue my informal Twi lessons. I finally mastered common

greetings and responses when the librarian interrupts the conversation. “Ah! Why do you

learn Twi? You are in Accra and should learn some Ga!” Immediately everyone begins

to laugh, knowing that Ga is much more difficult to speak. I heard Twi being spoken

around me the most, and had previously studied another Akan dialect while in Cape

Coast, so navigating basic phrases wasn’t too difficult. She begins to teach me basic Ga

56

Jeffery K. Olick. “Collective Memory: The Two Cultures.” Sociological Theory 17: 335.HL

Figure 5.1 Male Dungeon at Fort Prizenstein

An African porverb made famous by Nigerian novelist, Chinua Achebe, has been graffitied onto the